Friday, April 30, 2010

Velocity as a source of growth

Blogging has been light this week since we took a quick trip to Palm Springs to watch the Palm Springs Follies—something everyone over the age of 55 should see at least once in their life. It's a celebration of how productive, healthy and happy you can be in your retirement years. The ages of cast members ranges from the mid 60s to 86!

Meanwhile, here's a quick look at M2 velocity updated with the latest stats on Q1 GDP growth. First quarter growth has been dissected by just about every analyst by now, but so far I haven't seen anyone looking at the behavior of velocity. On an annualized basis, M2 money fell by 1.5% in the first quarter, while nominal GDP rose by 4.1%; thus, M2 velocity (measured by dividing GDP by M2) rose by 5.7%. You might say, in other words, that rising money velocity was by far the dominant factor in the first quarter economic expansion. Rising money velocity is the flip side of falling money demand, and money demand is falling because confidence is on the rise. Money that was hoarded during the panic of late 2008 and early 2009 is now being spent again. The public is divesting itself of money that is no longer desired, and that has fueled an increase in general economic activity. As the chart suggests, this very important change on the margin is potentially still in its infancy.

This is exactly what the Fed has been trying to do for the past 18 months. First, the Fed had to massively increase the money available to economy (by flooding the banking system with reserves) in order to offset the economy's massive increase in the demand for money at the height of the panic. That served to halt the downward spiral early in 2009, and the economy then hit bottom in mid-2009. Since then, the Fed has continued to over-supply money to the economy by keeping short-term interest rates near zero, with the intention of encouraging a decline in the demand for money. Who wants money or cash equivalents (e.g., money market funds) when they pay zero interest?

We've now had over nine months of declining money demand (rising money velocity), and rising real and nominal GDP growth. By the looks of things (e.g., strong commodity prices, V-shaped recoveries in manufacturing and exports), it appears to me that this process is self-sustaining and that we should therefore see continued growth in the months and quarters to come. I see no reason to change my long-held forecast of 3-4% real growth.

UPDATE: As my friend David Gitlitz points out, the evidence of rising money velocity also reinforces my long-held concern that inflation is likely to rise.

Rationale in a nutshell: Inflation is a monetary phenomenon that occurs when the supply of money exceeds the demand for holding it. We know that the Fed has massively increased the supply of money, by 1) holding short-term rates at close to zero for the past 18 months, and 2) more than doubling the monetary base through massive purchases of mortgage-backed securities. Rising money velocity is the flip side of declining money demand, so rising M2 velocity reveals that the public's demand for money is declining. Supply is up, but demand is down, and the rising prices of sensitive assets such as gold and commodities would appear to confirm that we have an oversupply situation on our hands.

Thursday, April 29, 2010

Easy Fed, strong gold

Gold continues its upward trend against the dollar, and it is making new highs almost daily against the euro. The Fed yesterday reiterated that it is still terrified (I'm exaggerating to make a point) that the economy remains weak and unemployment remains high, so it plans to keep interest rates very low for a long time. The prospect of an "extended period" of zero yields on cash and cash equivalents is driving investors to anything that shows signs of life these days, and gold now has a 9-year rising trend in place. Gold's current uptrend started almost the same day that the Fed belatedly recognized that the economy was weakening in the wake of the dot-com crash, and as a result of extremely tight monetary policy from 1997 through 2000. Since 2001, the Fed has been much more concerned about the strength of the economy than about the outlook for inflation. That is one big reason why gold is doing so well.

Obama's choice of three new Fed governors does little to reassure investors that the Fed will ever pay more attention to the value of the dollar than it does to the health of the economy. Indeed, all three picks promise to be firmly in the "dovish" camp when it comes to the hardest choice any central banker has to face: whether to tighten to defend the value of its currency, or to ease to support the economy.

While this is an ugly picture, it is also the case that measured inflation has been relatively tame for many years. The CPI has risen at a compound rate of 2.45% over the past 10 years; 2.0% over the past three years; and 2.4% over the past year. The early warning signals of future inflation, however, are not so good. Gold is a prime example, as are commodity prices, a record-steep yield curve, and a dollar that is only marginally above its all-time lows in terms of purchasing power relative to other currencies.

On balance, and given the reinforced makeup of the Federal Reserve, I think investors need to be concerned about higher, rather than lower, inflation in the years to come.

And the fact that gold is making new highs against the euro and almost all other currencies, means simply that our Fed is not the only central bank that is deciding to err on the side of ease. This is a global phenomenon. The forces of inflation are very likely to win out over the forces of deflation.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Commodities say forget Greece

I last featured industrial commodity prices a month ago, and I note that they have since risen some 3-5%. Both of these charts reflect prices of a variety of industrial commodities, many of which do not have futures contracts associated with them and are therefore at least somewhat immune from speculative forces.

Commodities across the board are marching onward and upward, apparently oblivious to Greek indebtedness, concerns about which have been plaguing markets for months. In the end, global growth—as is strongly reflected in the commodities markets—is one sure-fire way of dealing with whatever fallout there may be from what will either be a bailout of Greece or a restructuring of its debt. To put things in context, Greek GDP is about $340 billion, which is about what the U.S. government is borrowing every three months. Fears of a default on Greek debt, which is somewhat larger than its GDP, have erased more than $1 trillion of global equity market capitalization, but Greece's total indebtedness, even when combined with other PIGS, is a small fraction of the global bond market. Keep your eye on the big things, like strong global growth and accommodative monetary policies, since those are likely to overwhelm the Greek debt situation.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

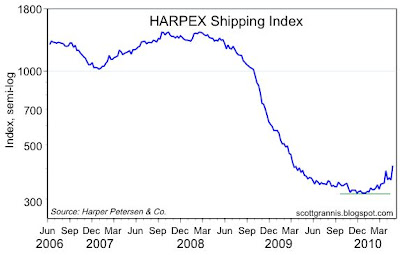

Shipping update

This rather obscure index of shipping costs in the N. Atlantic has turned up in significant fashion in the past month or so, after having been very weak for most of the past year. I don't know much about this index (as I've said before), but where there's smoke there is undoubtedly fire. Shipping activity must be picking up, and this has almost nothing to do with China or with commodities. This is a clear positive for the outlook.

Consumer confidence is still very low, and that is good

The Conference Board's measure of consumer confidence rose more than expected this month, but as this chart shows, it is still in the dumps. Consumers remain extremely worried about high unemployment, out-of-control fiscal policy, the big decline in housing prices, the threat of higher taxes (a VAT tax, which the administration seems to be flirting with, would hit everyone, particularly the struggling middle class), and equity prices which haven't made new highs for over a decade. There is no shortage of things to worry about.

As a contrarian and as a bull on the prospects for the equity market, I take a good measure of comfort from this. I don't see how equities could be overvalued in an environment that is chock-full of worries and perceived risks.

The risks are so plentiful and widespread that short-term interest rates have been almost zero for more than 18 months now. Trillions of dollars are sitting in cash that pays almost nothing, and the only explanation for why the money remains in cash is that the owners of the money are terrified of the risks they perceive. Even the Fed is so concerned about the economy that they have been unwilling, so far, to entertain even tiny rise in interest rates. (This may well change with the FOMC meeting announcement tomorrow, and I hope it does.)

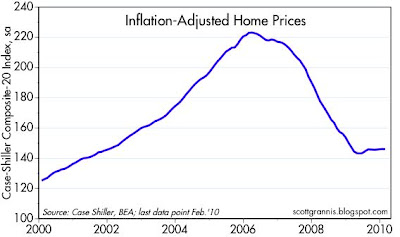

Home price update: still relatively stable

These two charts are my inflation-adjusted versions of the Case Shiller home price data. The top chart shows the composite index of 20 large metro areas, while the bottom chart goes back much further in time but shows only the top 10 areas.

I note that prices have been relatively stable for the past year. This is a good sign that the price adjustment process has done its job, and that a 35% decline in real prices was enough to allow the market to clear. Mortgage rates have also declined in recent years, further adding to the affordability of homes and further enhancing the clearing process. This is exactly what you would expect from a market that suddenly found itself with a huge excess inventory of high-priced homes; prices have to fall by enough to entice new buyers into the market.

Many observers continue to believe that this plateau in home prices is only temporary, and that it will be followed by yet another plunge, triggered by an avalanche of foreclosures that are set to hit the market over the next year or so. The second chart might support that notion, since it shows real prices today are still about 40% above their 1987 levels. But I have two reasons why that may not be a valid point: 1) prices in 1987 were relatively depressed, coming at the tail end of the housing price slump that began in the early 1980s; and 2) real housing prices tend to rise over time by a little over 1% a year, and the rise in real prices shown in the second chart works out to 1.5% per year annualized. I can't say definitively that prices won't fall further, only that it is not unreasonable to think they won't; prices today may be pretty close to their long-term equilibrium (or mean-reverting?) levels.

Monday, April 26, 2010

Corporate profits to rise 32% in coming year?

Bloomberg today is reporting that equity analysts (collectively) are estimating that profits on the S&P 500 companies will rise 32% over the next year (which data point I've added to the above chart). That would put profits at $85.96/share, just shy of the record $89.93/share registered in September 2007. That adds up to a pretty significant V-shaped recovery I'd say, and it also says that stocks are not expensive at all at current levels.

Dallas Fed Manufacturing Index looks very healthy

The Dallas Fed's index of manufacturing activity came in stronger than expected for April. Here are some excerpts from a Bloomberg story on the subject:

Texas factory activity increased for the sixth month in a row ... more producers reported increased activity ... 40% of respondents noting increased output ... indexes for capacity utilization, new orders and shipments showed marked increases ... growth rate of orders index jumped to its highest level since June 2006 ... employment index signaled further job growth, with the share of firms hiring workers rising to 22 percent ... wages and benefits index rose as the share of respondents noting increases doubled from 10 percent to 20 percent ... firms remain optimistic about their six-month outlook.

It would be hard to ask for more positive and optimistic news than this.

Friday, April 23, 2010

Used car prices continue to rise

Used car prices have risen over 20% since the end of 2008. Not surprisingly, auto sales are up 14% over the same period. I take this as one more indication that deflation is dead. Here's how the folks at Manheim explain it:

Pricing strength in the wholesale used vehicle market became more broad-based in the first quarter of 2010 as record tax refunds and improved retail credit availability reinvigorated the market for lower-priced vehicles. Meanwhile, prices for late-model, higher-priced, units stayed strong despite the increase in new vehicle incentive activity in March.

Incentives helped new vehicle sales, but didn't hurt used vehicle values. March brought forth a significant increase in incentives (mostly in the form of no-down, low-rate, financing or lease deals) from a variety of manufacturers, some of whom - such as Honda - have generally stayed away from such promotions in the past.

On a year-over-year basis, all market classes of vehicles are up significantly in pricing and, in recent months, the differences between individual market classes have moderated. Likewise, the relative difference in price performance between the various price tiers has also evened out.

In short, demand is strong and there is no shortage of money.

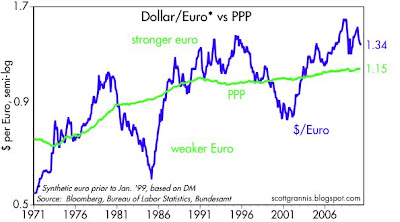

Despite the problems in Greece, the Euro is still strong

This chart serves as a reality check to all the hand-wringing over the problem with Greek indebtedness. Greece has a problem, no question, but it could be solved by simply cutting government spending and not raising taxes. Even if Greece were to default on its debt, it wouldn't be nearly as tough on global financial markets as the subprime disaster or the Lehman failure; it would likely involve a restructuring of Greek debt that would cost bondholders some sizeable fraction (but much less than 100%) of their value. Default risk on Greek debt is now somewhat higher than that of your typical junk bond. Greece's problem is dragging down the euro because Greece might risk the unthinkable by pulling out of the euro and printing drachmas to inflate itself out of debt (which is simply another way of restructuring its debt, but probably the worst and most stupid way).

Despite all the problems, the euro is still relatively strong compared to the dollar—about 16% above its purchasing power parity according to my calculations. You might say that this is the market's way of telling us that on balance the outlook for Europe is still better than the outlook for the U.S.

Strong growth in capex is very bullish

More very good news on the economic front today, with the release of unexpectedly strong data on capital spending by US businesses. This is one more of those V-signs of recovery. Capital spending is up about 13% from a year ago, and as the second chart shows, that's almost as strong as it ever gets. Strong growth in capex tells us a lot of important things: businesses are confident in the future and thus willing to take new risks; businesses are generating strong profits growth to fund new investment; and new investment today, by purchasing the tools and building the equipment that make labor more productive, is sowing the seeds of future growth and rising living standards. Capex is one of those things that feed on itself; the more we invest in productivity, the stronger the economy is likely to be.

To be sure, the level of investment is still quite low compared to where it's been in the past. But it is clearly moving in the right direction, and it's moving at pretty good clip. It's particularly impressive that business investment is so strong despite the tremendous amount of uncertainty that exists with respect to out-of-control federal deficits and the threat of higher tax and regulatory burdens. Just imagine how good things could be if these clouds of uncertainty weren't rolling overhead.

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Inflation at the producer level is alive and well

Thanks mainly to rising food and energy prices (in the past six months, food prices are up at a 13% annual rate, as Brian Wesbury points out), producer price inflation rose to 6% in the past year. Core inflation at the producer level remains pretty tame, but I note that the core PPI is up at a 1.9% annual rate in the past three months. It wouldn't be usual if the core PPI measure picked up further in the months to come, since the headline measure has tended to lead the core measure since the 2001 recession. Brian agrees, adding:

... core prices are showing higher inflation deeper into the production process. Core intermediate prices were up 0.7% in March and are up at a 6.3% annual rate in the past six months; core crude prices increased 6.0% in March and are up at a 41.1% annual rate in the past six months. These figures suggest the placid core price measure for finished goods will eventually start going up much faster.

More signs of a housing bottom

Data released today provide more support for the theory that we have seen the bottom in housing. The first chart is an index of the stocks of 18 leading home builders. It has reached a 19-month high, and is up 140% from its March '09 low. The second chart is the result of a survey of home builders that covers questions on present sales, sales expectations, and prospective buyer traffic. It is still quite low, but has more than doubled from its January '09 low. The third chart shows a continuing decline in the supply of unsold homes on the market. The pace of the decline looks very much like what occurred in early- to mid-1980s housing market recovery. The fourth chart shows a clear bottoming in the number of existing homes sold (the spike late last year was related to the anticipated end of the home buyers' credit).

Add to these signs of resurgent activity the fact that mortgage rates are at or very near all-time lows; that housing prices in 20 major markets have dropped by one-third in real terms since reaching a peak four years ago; and that signs of a general economic recovery are widespread. The resulting picture becomes quite clear: the great housing market bust is over, and a new growth cycle is underway.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Disturbing parallels between the U.S. and Argentina

I touched on this subject in a post last month, and return to it because creeping socialism (or American Peronism, if you will) is a very slippery slope with disastrous long-term consequences. I know Argentina and its history very well. In fact, I once had to take a high school equivalency exam that included a rigorous test and essay on Argentine history, and my first job as an analyst in 1981 was to prepare an extensive report on the outlook for Argentina. Additionally, I lived there four years in the late 1970s. My wife and I have countless friends and relatives that we have visited dozens of times over the years since. As much as I love the people, the food, and the wine, I detest the Argentine government for the unimaginable economic pain and suffering it has inflicted on its people. I've witnessed first-hand the destruction of Argentine living standards over the past 35 years.

I never thought I would see the day that counting the number of parallels between the U.S. and Argentina would require the fingers of two hands, much less just one. But Richard Rahn does just that in a very well-done article in today's Washington Times. Excerpts:

I never thought I would see the day that counting the number of parallels between the U.S. and Argentina would require the fingers of two hands, much less just one. But Richard Rahn does just that in a very well-done article in today's Washington Times. Excerpts:

Argentina has extensive import bans and controls. The Obama administration has been advocating protectionist trade policies and has opposed the ratification of previously negotiated trade agreements.We are clearly headed in the wrong direction, and it's now up to the people to demand change for the better come November. I think it can be done. If not, the long-term consequences are very disturbing.

Argentina has income tax rates roughly equivalent to those in the United States but also has a value-added tax (VAT) and a wealth tax. Officials of the Obama administration and some members of the U.S. Congress are flirting with a VAT.

Argentina has continued to run inflationary monetary policies while at the same time attempting to treat the symptoms through price controls. The U.S. Federal Reserve has greatly increased the money supply, which is likely to produce future inflation. Officials of the Obama administration, at times, have advocated price controls of insurance companies, medical suppliers, financial institutions and even fees for carry-on luggage on airplanes.

Argentina's largest bank is state-owned, as are a number of its other banks. The Obama administration forced a number of large American banks to become partially government-owned. The two largest mortgage institutions in the United States - Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac - are now largely government-owned-and-controlled.

Argentine courts are slow and corrupt. Property rights are not secure, and the government has willfully understated inflation statistics, causing foreign and domestic bondholders to lose much of their investments. The Obama administration unilaterally took away bondholders' rights in the GM and Chrysler cases and, in essence, took their assets and turned them over to the unions that had supported Mr. Obama.

Argentina has extensive labor regulations to favor unions, which greatly increase the cost of hiring. The Obama administration has supported costly labor regulations that the unions favor, which eventually will drive up the cost of hiring workers and result in higher unemployment.

Argentina has a long history of deficit spending, which, in turn, has made government debt burdens so high that the government refuses to pay the debt to the private domestic and international debt holders. Over the next 30 years, economists ... estimate ... that the U.S. public debt will rise to between 200 percent and 500 percent of GDP. (It is now about 60 percent.) Debt levels of 200 percent to 500 percent cannot be supported; hence, the debt holders will face erosion of their capital through either inflation or nonpayment.

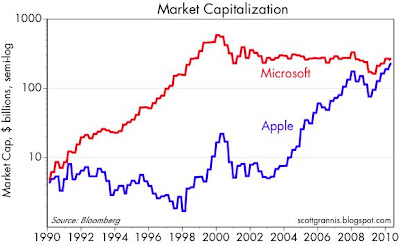

I stand corrected

As an alert reader pointed out, the difference between the market caps of AAPL and MSFT is $40 billion, not $30 billion; I think my calculator failed me yesterday. Nevertheless, this is perhaps the most impressive David vs. Goliath story in modern finance: Apple's comeback from the brink of oblivion 12 years ago.

Another very interesting observation occurs to me: the amount of market cap that Microsoft has lost ($311 billion) since its late 1999 peak ($586 billion) is substantially more (32%) than Apple's market cap today ($235 billion). Even after adjusting for its $32 billion cash payout several years ago, and its ongoing dividend, it's remarkable the value that has been destroyed by Microsoft's inability to innovate.

The bond market's inflation-forecasting track record isn't very good

The market—which reflects the cumulative wisdom of billions of participants—is pretty good at discovering information and pricing things efficiently. I think there is great value to be found in market pricing, which is why I pay a lot of attention to things like the value of the dollar, credit and swap spreads, gold, commodities, the shape of the yield curve, and the implied volatility of options. But the market can and does make mistakes. One case in point is the bond market's ability to correctly anticipate future inflation.

I think these two charts provide evidence of the bond market's fallibility when it comes to inflation forecasting. If the bond market were an excellent judge of future inflation, then interest rates would always, after the fact, offer investors a yield that exceeded inflation. Real yields, in other words, would tend to be somewhat positive most or all of the time.

The first chart focuses on the past 50 years of interest rates and inflation. Note that in the early 1960s, when inflation was very low and stable, bond yields were also low and stable, but also consistently higher than inflation. Around 1965 inflation started rising, and bond yields struggled to keep up. If you bought the 10-yr Treasury bond in 1970 it yielded about 7%, but inflation over the next 10 years proved to be almost 8% per year. T-bonds were a lousy investment in real terms throughout the 1970s.

The bond market finally learned its inflation lesson by the early 1980s, as 10-yr Treasury yields soared to 14%. Once burned, twice shy: no one was going to be foolish enough to trust their money to the bond market unless they received a handsome premium over inflation, which was expected to be in the double digits for the foreseeable future. However, thanks to tough monetary policy from the Volcker Fed, inflation subsequently collapsed. As a result, real yields were enormous in the 1980s, and investors in T-bonds earned huge real returns (I should know, as I was lucky enough to buy 30-year zero coupon Treasuries in 1982 and 1983 for my IRA account—an investment which more than tripled in value over the next 10 years).

In short, the bond market underestimated inflation throughout the 1970s, and overestimated inflation throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

The second chart shows real yields (the difference between 10-yr yields and consumer price inflation) over a very long time horizon. As should be obvious, the bond market made some huge inflation-forecasting mistakes in the 1930s and 1940s.

On average, real yields on 10-yr Treasuries have been 2.6% per year since 1925, and that's the value that the market seems to gravitate around. But note how real yields have been for the most part below average since the early 2000s. Not coincidentally, monetary policy has been for the most part quite accommodative over this same period. The Fed has been unconcerned about inflation, and so has the bond market. I believe that is still the case today. Both the bond market and the Fed are underestimating future inflation, just as they did in the 1970s.

Why? Because the bond market pays too much attention to growth, and not enough to sensitive prices. Because the Phillips Curve theory of inflation is still dominant, despite having been disproved countless times over the years. See my many discussions of this here if you want more background.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Is this a great country or what?

Apple today reported a 90% gain in second-quarter profit; net income rose to $3.33/share, from $1.79 a year earlier; sales rose 49% to $13.5 billion, topping expectations of $12 billion; shares rose 6% in after-market trading. Apple's market cap is now only $30 billion shy of Microsoft's.

Current expectations for future interest rates

Here is Bloomberg's calculation of where the market expects Treasury yields to be in 1, 2, and 5 years (current yields are shown in the red line at the bottom, 5-year forward yields in the green line at the top). The market is expecting the Fed to raise the funds rate by about 1 percentage point over the next year, and another percentage point over the subsequent year. To me, this confirms what I pointed out in my previous post, namely that the market is not expecting great things from the economy over the next few years.

The bond market sees little inflation risk and very slow growth

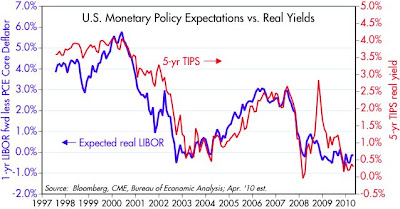

Always on the lookout for the key assumptions that are lurking behind market prices, I offer this update to similar posts here and here. Real yields on TIPS are, I believe, very good indicators of the bond market's growth and inflation expectations. Currently they are telling us that the bond market expects sub-par growth and no significant increase in inflation.

I detect no sign that the bond market is unusually concerned about future inflation. 5- and 10-year breakeven spreads are in the range of 2.25-2.35%, which is actually lower than the 2.45% that the CPI has averaged over the past 10 years. The 5-year, 5-year forward breakeven spread is about 2.65%, again very much in line with what we have seen in the past. 10-year Treasury yields today are at the same level (just under 4%) as prevailed during the early 1960s, which was a time when inflation was extremely low and stable—about 1.5% per year.

I infer from the chart above that the bond market is not concerned at all about any significant tightening of monetary policy over the next year. The level of yields on 5-year TIPS is consistent with an expectation that real yields on short-term interest rates will be roughly zero. That expectation (of no Fed tightening, which I define as increasing the Fed funds rate by more than the increase in inflation) is in turn consistent, I believe, with a view that economic growth is likely to be sub-par (consistent with the popular "new-normal" forecast for 2-2.5% growth). If economic growth were expected to be 3-4% or more one year from now, I have to believe that the bond market today would be expecting at least some modest tightening, if not significant tightening.

Since there is no reason to believe that the expectations driving the bond market are any different from the expectations driving the equity market, I can further infer that there is little reason to believe that the equity market is a bubble waiting to pop. The capital markets today are priced to very conservative and unexciting assumptions about the future.

Still no sign of a threat to housing

Despite the conclusion last month of the Fed's program to purchase $1.25 trillion of mortgage-backed securities, today there is no sign that this has had any meaningful impact on mortgage interest rates. In fact, rates on 30-year fixed-rate jumbo mortgages are now as low as they have ever been. Furthermore, the spread between jumbo and conforming mortgages is now down to 50 bps, not too far above the 25 bps average that prevailed during the 10 years ending mid-2007. The absence of any upward pressure on mortgage rates, coupled with the continued tightening in conforming/jumbo spreads, is a good indication that the mortgage market is efficient and sufficiently liquid. If there's a threat to the housing market out there, it is not hiding in the bond market.

Message to homebuyers: interest rates on 30-year fixed rate mortgages are extremely attractive from an historical perspective, since they are now about as low as they have ever been. Given the great uncertainty surrounding future monetary policy (i.e., how much will the Fed have to raise short-term rates to keep inflation at bay, given the Fed's massive $1 trillion injection of bank reserves), fixed rates also look very attractive relative to adjustable rate mortgages.

Monday, April 19, 2010

Real estate prices still appear to have bottomed

The March value of Moody's Commercial Property Index fell, but in the great scheme of things I don't see this as significant. As this chart shows, prices of residential and commercial real estate have already experienced huge declines (29% and 42% respectively) in recent years. The market has been working very hard for the past four years to reduce the inventory overhang of homes and commercial space by slashing prices and slowing the pace of new construction. It appears to be working.

Commercial real estate has been lagging the moves in residential real estate, and residential prices bottom over a year ago, so it's reasonable to assume that commercial property prices are now in a bottoming process.

As evidence of a bottom in real estate prices accumulates, this paints a very optimistic picture for the economy and financial markets going forward. Since real estate figures importantly as collateral behind all sorts of debt obligations, reducing the likelihood of future price declines adds significantly to the value of collateralized debt. And this, in turn, provides substantial support to the value of all institutions that carry significant real-estate-backed assets on their balance sheets.

As I've been noting for quite some time, the prices of securities backed by homes and commercial real estate loans have risen significant in the past 6-9 months. There are just too many signs of a bottom here to ignore.

Leading indicators continue to look very bullish

As I said in a previous post, I don't usually put much stock in the Leading Economic Indicators published by the Conference Board. But the pronounced rebound in this statistic, whose growth rate is shown in the above chart, is so strong that it is probably risky to ignore it. Mark Perry has some amplifying comments here. I note that the current rebound is the third-strongest on record.

It then occurred to me to put together this next chart, which shows the level of the LEI index on a semi-log scale. I note that the index was roughly flat throughout the 1965-82 period, when equities delivered negative real returns for 17 years. But today the index appears to still be following the significant uptrend which began in late 1982. I don't want to make a big deal of this, but I do think it's worth noting. I've seen a number of people attempting to make the case that the bear market which began in 2001 is going to be a replay of the 1965-82 bear market. While I still worry that inflation will be higher than the market expects in coming years, there is no sign yet that inflation will be anywhere near as bad in coming years as it was in the 1970s.

Commodities continue to boom

The amazing action in the commodities markets continues. This measure of raw industrial commodity prices is only 2.6% below its all-time high, and looks set to break new ground soon. The commodities that make up this index are not the sort of commodities that lend themselves to massive speculative activity, so I think the price action here mostly reflects strong global demand. Demand can be influenced by monetary policy, of course, because easy money tends to boost people's desire to own tangible things, and these commodities are the raw materials for a lot of "tangible thing" production. Easy money + strong global growth = strongly rising commodity prices.

The message to investors: the action in the commodity markets is a strong sign that deflation risk is minimal, if nonexistent. Yet the Fed and many market participants continue to fear deflation: that is one reason why the Fed has kept interest rates at zero for a year and a half, and it helps explain why Treasury yields are still extremely low from an historical perspective. I think the market is over-estimating the potential for downside risk, and that means there is still plenty of upside in equities. Full disclosure: I am long equities, TIPS, corporate debt, and emerging market debt at the time of this writing.

Friday, April 16, 2010

The counterintuitive relationship between money growth and inflation

While on the subject of commodities, monetary policy, and inflation, I thought I would update this chart that compares M2 growth (M2 being arguably the best measure of money) and consumer price inflation. What strikes me in this chart is the strong tendency of these two lines to move in opposite directions. For example, M2 growth surged from 1995 through 1999, yet inflation fell; very slow M2 growth from 2004 through 2006 was accompanied by rising inflation; M2 growth plunged in 2009, yet inflation surged.

My explanation for this is that money velocity is what is really at work behind the scenes. M2 is typically called a measure of money supply, but it really is a better measure of money demand. When M2 growth slows, it is because money demand is slowing and money velocity (money velocity being the inverse of money demand) is rising. Rising velocity makes a given amount of money support a higher level of prices. Rising velocity is also indicative of a phenomenon in which people try to reduce their money balances in favor of owning more things, and that is a classic symptom of inflationary psychology.

So the fact that M2 growth has been almost zero over the past six months, and only 2% over the past year is both encouraging and troubling at the same time. That's because it means that the velocity of money has turned up sharply, and that in turn is helping to fuel more spending and higher prices.

Oil production is driven by real oil prices

I offer this chart to illustrate just how much the dollar value of commodities can affect the commodities market. What it shows is that the real price of crude oil (in dollars) has a significant impact on oil production via changes in the number of oil and gas rigs that are operating around the world. There is a long lag involved, of course, between increased oil drilling and actual production (several years I believe), but the response from oil producers to changes in the real price of oil is strong and quite obvious.

For example, note that real prices fell sharply from late 1996 through early 1999. In response, the active rig count started falling in late 1997, dropping fully 52% by mid-1999. Real prices then shot up, and that was followed by an eventual tripling in the number of active drilling rigs by 2008.

There's good news and bad news here. On the one hand it's good to know that the price signal does play an important role in the oil market. With real prices relatively high these days, producers are ramping up the exploration and production efforts and this should keep prices from climbing too high. But on the other hand, erratic monetary policy, to the extent it influences oil and other commodity prices, can result in a real roller-coaster ride for the industry over time. First, prices rise, which then encourages more exploration, which eventually results in increased supply, which then helps prices decline. Lower prices then discourage production, which then results in less supply, which eventually helps prices rise.

We would all be far better off without this tremendous price volatility. This is one reason why the Fed should pay more attention to commodity prices, since I do believe they are quite sensitive to changes in monetary policy, as I tried to point out in yesterday's post. If commodity prices were an important input to monetary policy decision-making, we might have not only less volatile commodity prices, but also lower and more stable inflation.

More evidence of a housing bottom

According to March data released today, U.S. housing starts have risen 30% from their all-time low (April '09). In addition, building permits increased 38% over the same period. And not surprisingly, the Bloomberg index of home builders' stocks bottomed last July and has since risen over 50%. And as I've pointed out before, the prices of home equity-backed securities are rising sharply. If this doesn't add up to a clear picture of a bottoming in the residential construction market, I don't know what would.

To be sure, this "bottom" has taken almost a year to form, which makes it the longest-drawn-out recession bottom since data began to be recorded in 1968. Also, housing starts in the winter months are full of seasonal adjustment factors which may or may not accurately reflect underlying activity. But an increase of 30% in just under a year is pretty impressive nonetheless, and hard to chalk up to seasonal or weather-related vagaries.

With most signs pointing to an end to the worst housing recession in modern history and a clear beginning to a housing recovery, the widespread angst over the homes remaining to be foreclosed and auctioned off seems overdone. The recovery is for real, thank goodness.

Thursday, April 15, 2010

The reflationary message of key commodity prices

Here's an interesting chart that puts key commodity prices—gold, crude oil, and industrial commodities—in perspective. I've recalibrated each so that they are equal to 100 as of Jan. 31, 1997. I chose early 1997 as a starting point, because I think that monetary, economic and inflation fundamentals were relatively stable around then. The CPI had been fairly steady at just under 3% for six years. Gold prices had been fairly steady at just under $400 for about 4 years. Industrial metals prices had been fairly steady for 2-3 years. The economy had been growing about 3% a year for 4 years. The dollar had been in a flat trend for 6-7 years.

From 1997 through 2003, we began to see the effects of monetary deflation, as the Fed tightened policy aggressively in an attempt to slow what was perceived to be an "overheating" economy. Commodities fell across the board during that period. From 2003 on, we saw the effects of monetary reflation, as the Fed responded to the deflation it had previously generated by keeping interest rates low for an "extended period." Commodity prices rose across the board during that period, not surprisingly. Then came the panic collapse of 2008, when the prices of almost everything declined as global demand evaporated But since then monetary policy has reverted to being very accommodative, demand and confidence have come back, and commodity prices are once again on the rise.

One thing about this chart really stands out: these key commodity prices have essentially tripled in the past 13 years. That works out to almost 9% inflation per year on average. Another interesting observation: gold prices and crude oil prices have risen by almost the same exact amount over this period. In addition, the ratio of gold and crude oil prices today (13 barrels per ounce of gold) is not too far off its average (17.8) for the past 50 years.

Message: these prices tend to move together over time, even though they are very distinct commodities. Gold has an intrinsic value derived from its beauty and durability; crude oil's value is purely as a source of energy; industrial metals are key inputs to most industrial processes and by extension, to economic growth in general. That they are all on the rise is a strong indication that monetary policy is increasing inflation pressures throughout the economy.

Exports continue to grow

Another update of a chart I first showed one year ago. Data on outgoing container shipments from the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach (which account for a about 40% of U.S. container traffic) show continued growth in export activity, at least through the end of last month. This data is a a reasonably good and timely proxy for the growth of US exports, which are reported with a lag. Export growth feeds directly into GDP, and it is also a measure of how strong the global economy is. From the looks of things, all systems are go. Los Angeles container shipments have rebounded about 50% from their late-2008 lows, and have almost returned to the highs of early 2008. More V-shaped recovery signs; sorry if this is getting to be a bit boring.

Global industrial production continues to expand

An update to an oft-featured chart. In the 12 months ended Feb. '10, Japanese industrial production rose 31%! U.S. industrial production is up 6% from its June '09 low, and has risen at a 6% annual rate in the past six months. Eurozone industrial production is up at a 11.5% annual rate in the six months ended Feb. '10. While the U.S. seems like the laggard based on these numbers, it is also the case that production never fell as much here as it did there. Taken together, these numbers all point to a substantial recovery from recession lows. All signs point to a continued global recovery, and that means more good news in the months to come.

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Inflation at the consumer level subsides

Inflation at the consumer level has turned out to be less than I have been expecting. Indeed, over the past three months the CPI is up only 0.9% at an annual rate, and the core CPI is actually down 0.18% at an annual rate. Much of the decline in inflation can be traced to "Owner's Equivalent Rent," the BLS's estimate of how much a homeowner would be paying if he were renting his home. OER is roughly unchanged over the past year, thanks to the depressed housing market. Abstracting from this, as Brian Wesbury points out, we find that "cash inflation" is up 3.2% over the past year.

I agree with Brian that sooner or later we will see CPI inflation moving higher. The CPI is the last place that true inflation trends will show up, because of the way it's constructed and because inflation at the consumer level is very "sticky." Wages don't change much or very fast in response to changing monetary policy, but gold prices, for example, can change on a dime. It can take years for a loss in the dollar's purchasing power to find it's way through the maze of the U.S. economy and through labor contracts. I think it makes a lot more sense to watch the leading indicators of inflation than it does to watch the official measures of inflation.

Sensitive prices that are set in real-time by the market are where the action is. On that score, we have the following evidence which points to higher, not lower inflation: 1) the dollar is weak against most other currencies, having lost one-third of its value in the past 8 years, 2) gold prices have risen 350% since 2001, and are within inches of their all-time highs, 3) industrial commodity prices are up strongly across the board, 4) oil prices have doubled in the past 16 months, 5) real estate prices have bottomed and are now rising in some areas, 6) short-term real interest rates are negative, meaning that effective borrowing costs are unusually low, 7) money velocity is on the rise, which effectively amplifies the Fed's extremely accommodative policy stance, and 8) the yield curve is extremely steep, a classic sign of easy money. I believe that these are all leading indicators of a coming acceleration in inflation at the consumer level that will likely unfold over the next year or so. You can't wait for the CPI to go up before realizing that inflation is a problem.

Retail sales surge

Retail sales have recovered quite nicely in the past year. As for the shape of the recovery, I think the bottom chart says it best: that's a V if I've ever seen one. No matter you slice and dice the retail sales numbers (e.g., ex-autos, or inflation-adjusted), the results are strong, and a whole lot better than the market expected just one year ago. However, sales still need to recover by another 10% or so before they catch back up to where they would have been absent the financial panic of 2008.

Skeptics will say that sales are up in large part thanks to stimulus spending, but I don't buy that. Stimulus spending, when viewed from a supply-side perspective, just takes money from one person's pocket and puts it in another's. It doesn't create new demand. Even some supply-siders will look at these numbers with some skepticism: How can demand have recovered so strongly without any meaningful growth in jobs?

I think that the recovery we see in these numbers is a function of monetary velocity. (See related posts here.) Consumers shut down their spending in late 2008 due to the huge panic and uncertainty surrounding what appeared to be a global financial crisis that would lead to massive bankruptcies and depression. The demand for money rose sharply as a result. Now that money is getting spent again; money that was stored up is once again flowing into the economy. It was a panic-driven recession, and once the panic subsided and people saw that they economy was going to survive largely intact, they ramped up their spending. This is an unusual recovery since this time a resurgence in demand is preceding a resurgence in jobs.

Once the rising money velocity story plays itself out (say, by early next year), we will probably see the pace of recovery slow back down. Growth from that point will be more a function of new investment and jobs creation than anything else. It might prove to be tough sledding, however, if tax rates rise as expected. But that's tomorrow's concern. For the moment it's just very nice to be getting back to some semblance of normality.

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

The dollar is still very weak

This is a chart of the Fed's measure of the dollar's strength vs. a large basket of other currencies and adjusted for inflation differentials. I think this is one of the best dollar indices available. As it shows, as of the end of February the dollar was only slightly higher (about 3-4%) than its all-time lows. This, despite the mountains of concerns that have supposedly arisen over the risk that Greek indebtedness could seriously threaten the future existence of the Euro. This is more evidence to back up the assertion in my previous post that market pricing still reveals relatively high levels of concern about the future of the U.S. economy.

Credit spreads reflect substantial progress but room for more

Here are two different looks at credit spreads. The top chart shows credit default spreads over the past few years, and the bottom chart shows corporate spreads (investment grade and high yield) going back over 20 years. The message of both charts is the same: credit spreads have narrowed significantly since the end of 2008, a clear reflection of dramatic improvement in the economic outlook; but spreads are still a lot higher than they tend to be during periods of relative economic tranquility.

This fits nicely with the thesis I have been fleshing out since late 2008. Markets were literally terrified in late 2008 and early 2009, consumed by fears of a global financial meltdown and a deep and lasting depression and deflation. This fear was sparked by the realization that the subprime crisis had morphed into a massively destructive force that culminated in the Lehman bankruptcy and the mad dash by governments all over the world to shore up their financial systems and economies with previously-unheard-of stimulus measures.

Fears were multiplied by the Obama/Pelosi/Reid $787 billion faux-stimulus budget which ushered in new visions of expansionary government and massive hikes in future tax burdens. Even as the market reached the pinnacle of its fears in early March of last year, I continued to believe that the economy was well on the way to healing itself, despite the headwinds of out-of-control fiscal policy and massively accommodative (and potentially hyperinflationary) monetary policy, and that the recession would end by mid-year. I pointed to declining swap spreads in October and November of '08 as the leading indicator of this improvement, which were then joined by rising commodity prices and a steeper yield curve.

By now it's pretty clear to most (though the NBER is still debating whether or not the recession has officially passed) that the economy is growing. In the space of just one year the debate has shifted from how deep and long the depression was likely to be to how weak or strong or durable the recovery is likely to be. The market was priced to Armageddon, and instead we got a recovery; that alone is enough to justify the 77% rise in the S&P 500 in the past 13 months. But the market is still not prepared to abandon its fears (e.g., of a double-dip recession, or a "new normal" recovery with meager, 2-3% growth and very high European-style unemployment for as far as the eye can see). The market is still demanding a substantial risk premium, in the form or credit spreads that are still historically high, implied volatility that is still historically high, PE ratios (using NIPA after-tax corporate profits) that are still historically low, and Treasury yields that are still historically very low.

The market is still very worried, and with good reason: the economy may be doing better than expected, but we are not out of the woods yet.

The Federal Reserve has more than doubled the monetary base since the financial panic set in, with enough excess reserves now in the banking system to potentially cause hyperinflation and the collapse of the dollar. With no move yet to drain reserves, the best the Fed can do to reassure the world is to lay out a plan to fully drain excess reserves within the next 5 years. The amount of monetary uncertainty this poses is nevertheless so great and so unprecedented that it is difficult for mere mortals to comprehend.

U.S. fiscal policy is out of control, with Congress effectively having abandoned all pretense at living within a budget. Unfunded liabilities of the healthcare, social security, and public sector pension systems are so large as to be clearly unsustainable, yet no one in government has proposed even the beginnings of a solution.

What is holding everything together so far is the U.S. economy's inherent dynamism, its oft-demonstrated ability to forge ahead despite great adversity, and the accumulating V-signs of recovery in many sectors (but not all, to be sure) of the economy. Just as important, but often overlooked, is the political dimension of our fiscal and monetary problems. There have been some seismic shifts in the political landscape in the past year (e.g., the rise of the Tea Party, the election of Scott Brown in MA, and polls that show a majority of Americans favor repealing the healthcare bill) that augur well for a dramatic shift in the balance of power in Congress come November.

If we do indeed see a major political shift take hold, and if it leads to measures that effectively restrain the growth of government and minimize the risk of higher tax burdens, then I think the there is a lot of room for improvement in a number of areas: tighter credit spreads, higher PE ratios, and lower implied volatility. I also think that progress on these fronts would most likely come hand in hand with higher Treasury yields and higher mortgage rates. I'm encouraged, and I remain optimistic for the future.

The commodity V-boom (2)

This may be the most V-shaped recovery of any I've seen of late. It's an index of the prices of some relatively obscure commodities (hides, rubber, tallow, plywood, and red oak) that are included in the larger Journal of Commerce index. Now, I would argue strongly that these commodities are simply not the object of speculators' affection. If I'm wrong, please point me to data which show that speculators are gobbling up tons of this stuff and storing it in massive warehouses around the world. There's a very thinly traded futures contract for rubber, but the fact is that none of these commodities have an easy way for speculators to accumulate large positions in anticipation of price increases. The inescapable conclusion here is that prices are up (and have reached a new all-time high) because global demand is strong. You can't argue with a bullish price signal like this.

Oh, and the last time this index surged was in the latter half of 2003, which just happened to be when the U.S. economy grew at a 5.2% rate.

Monday, April 12, 2010

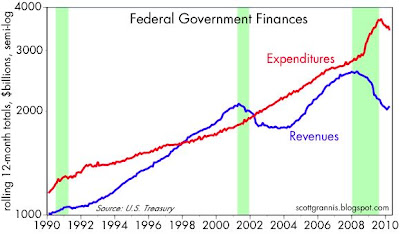

Federal budget outlook still deeply troubling

Although in the past few months there has been some improvement on the margin in the state of the federal government's budget, the overall picture is still deeply troubling. The improvement comes mostly from a decline in outlays (measured on a rolling 12-month basis), which in turn is a function of the running-off of the crisis-mode spending that occurred in the early months of last year. In addition, in the past few months there has been a slight firming in revenues, which is not surprising given the improvement in the economy since last summer.

But unless big changes are made to the government's spending plans, we are likely to see spending rise back up to 25% or more of GDP in the years to come, especially if healthcare reform is implemented. In an optimistic scenario in which the economy continues to post growth of 3-4% per year, revenues could move back up to 18% of GDP, but that would still leave a deficit of 7-10% of GDP. The deficit over the past 12 months is just under $1.4 trillion, and even "optimistic" numbers such as these would yield annual deficits of $1.1 to $1.7 trillion two years from now.

Thus, our debt to GDP ratio is on track for 100% within the foreseeable future, with the lion's share of the deterioration coming from government spending fueled mainly by transfer payments and entitlement programs. We will be passing on a huge debt to future generations with nothing much to show for it save a growing and cancerous culture of dependency. In a best-case scenario, this will mean a substantially slower trend rate of growth in the future, and lower living standards for most of us than would otherwise have been possible.

The prospect of trillion-dollar deficits is already driving calls for higher taxes on the rich, but that has limited potential to solve the problem since the rich are already paying most of the income taxes these days. The only way to generate a significant increase in revenue is with a VAT tax, such as is being proposed by Paul Volcker, that would land squarely on the shoulders of the middle class.

In the meantime, the prospect of higher income taxes next year is probably helping to drive the improvement in the economy and in the budget situation this year. That's because people have a powerful incentive to accelerate the recognition of income and capital gains to take advantage of today's lower rates. This positive dynamic has its cost, of course, and that will be seen next year in the form of slower income growth and reduced capital gains realizations. (This reminds me that the capital gains tax is the only tax you can legally avoid, simply by not selling whatever you hold at a gain.)

We have seen this dynamic happen several times in the past, as the above chart shows. Prior to the scheduled increase in capital gains taxes in 1987, capital gains realizations surged in 1986, only to collapse once the higher rates kicked in. Conversely, the reduction in the capital gains tax rate in the late 1990s produced a surge in capital gains realizations in subsequent years. Yet despite the abundant evidence that changes in tax rates have profound effects on people's tax strategies and their incentive to work and invest, OMB routinely projects (and politicians happily agree) that higher tax rates will always produce higher tax revenues, and vice versa. Unfortunately it just ain't so: higher tax rates next year could well lead to an even worse budget situation.

Where does this leave us? It's my hope and expectation that this budget picture is ugly enough to grab the electorate's attention. That attention will become laser-focused by the emerging discussion of the need to close an enormous budget gap with hugely higher taxes. With a little luck the electorate will decide we are on an unsustainable path (i.e., too much spending) and vote for change of the positive variety (i.e., less spending). So even though the outlook is deeply troubling, there is still plenty of reason to be optimistic about the future.

Friday, April 9, 2010

ABS, CMBS prices continue to rise

The top chart shows the price of an index of home equity-backed securities, while the bottom chart shows the price of an index of commercial mortgage-backed securities. Both show strong price gains, and I would note that prices have been rising since last summer. It's particularly interesting to see these price gains come at a time when the whole world is anticipating a new wave of home foreclosures and widespread distress in the commercial real estate market. These charts are saying the reality is not likely to be nearly as bad as the hype.

This also provides more confirmation that the real estate market has bottomed and may even be improving. A year ago the prices of asset-backed securities such as these were priced to Armageddon—to the expectation of truly massive defaults nationwide. Now they are priced to merely difficult conditions, but that represents a huge improvement.

These charts also suggest that asset backed securities such as the ones represented in these indices, which were marked down severely last year by many institutions because they were considered "impaired," will at some point be marked up, resulting in very welcome additions to corporate profits.

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Gas is $9 a gallon in the U.K.

This is a milestone of sorts, until a new record-setting price inevitably appears as a result of the accommodative monetary policies of the worlds' central banks and the global mania for curbing carbon emissions. Gasoline has now hit $9 a gallon in parts of the U.K. Can U.S. consumers even imagine a price that high? It wouldn't be too hard to achieve, given the weakness in the dollar, the Fed's super-accommodative monetary policy, the renewed push for a cap and trade regime or a carbon tax to reduce hydrocarbon fuel usage, and the rising ethanol requirements (ethanol being a less efficient fuel).

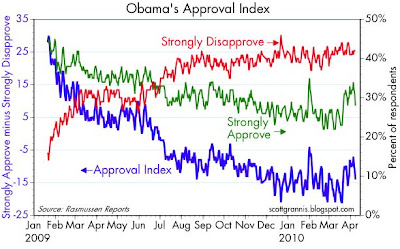

Obama's negatives continue to outweigh his positives

In my view, this data from Rasmussen paints a picture of a deeply unpopular president. More than half of the people consistently have disapproved of his job performance for most of the past 4-5 months. The bounce in his "approval index" that occurred in the wake of the passage of the healthcare reform bill was most likely due to moderates in his party cheering his apparent Congressional success. But his negatives have remained consistently high for many months and have not wavered. If I'm right, we should see his "approval index" soon return to its previous lows, as independents and liberals despair over his leftward overreach on ever-more issues. His efforts to appease Russia with today's nuclear arms reduction treaty, and his utter disregard for Israel and the U.K., traditionally among our staunchest allies, are not going to play well with the majority of the people. At the rate things are going, I would expect to see this index plumb new lows before too long.

I will be very surprised if the November elections do not result in huge losses for the Democrats. More importantly, I think the elections will mark a key "tipping point" in U.S. politics, in which the political spectrum begins to be divided not on social issues (abortion, gay rights, etc.), but on the proper role and size of the government. Obama and the liberals have made it clear they want more government, but I am convinced that the great majority of the people want less government.

I plan to attend my local Tea Party rally next week (April 15), and I encourage every freedom-loving and big-government-hating citizen to do the same.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)