Many people are saying that our national debt—which now exceeds $17 trillion and is growing by more than $1 trillion per year—is a disaster just waiting to happen. Right? Well, not exactly. Even though federal debt has soared relative to GDP in the past decade, the burden of the debt is about as low as it's ever been. Still, the growth in debt does reflect some structural problems that are working to keep the economy from achieving its full potential.

Let me put things into perspective:

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the the swelling size of our national debt, which is correctly measured as the amount of Treasury debt that is held by the public, and that now stands at $17.16 trillion. Too often I see people saying the national debt is over $23 trillion, but that figure is inflated since it includes some $6 trillion which the government owes to itself (i.e., excess revenues that the social security administration has "lent" to the Treasury). You can see the current figures

here.

Chart #1 uses a semi-log scale for the y-axis, so that means that a constant slope is equal to a constant rate of growth in nominal terms. Note that the slope of the line for the past 7-8 years has been flat (i.e., the growth rate has been constant). Note also that the slope was steeper in the mid-80s and in the 2008-2012 period. Federal debt is growing, but not nearly as fast as it was growing in other times.

Chart #2

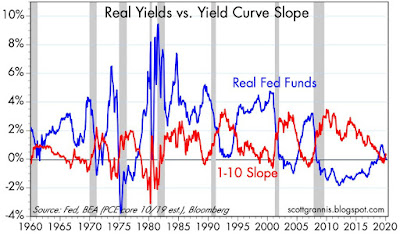

It's common to hear people argue that with so much debt being issued, interest rates will inevitably have to rise. But as Chart #2 shows, the size of the debt (when measured relative to the size of the economy, which is essential, since a bigger economy can support a bigger debt load, just as households can with rising incomes) has tended to move in a very counterintuitive fashion with respect to interest rates. Slower growth in debt tends to coincide with rising interest rates, and faster growth in debt tends to coincide with falling interest rates. What explains this? It's tempting to search for an explanation for this relationship, and I make an attempt later in this post.

Chart #3

Nevertheless, the size of federal debt relative to the economy is far less important than the prevailing level of interest rates, as Chart #3 demonstrates. The true burden of the national debt is not the amount we owe but the ratio of interest payments on the debt relative to our national income (GDP). Because interest rates are at historically low levels, the current burden of our national debt is about as low as it has ever been, even though the debt has soared to 78% of GDP.

Chart #4

It's worth noting that households' debt burdens (Chart #4) are also about as low as they have ever been. Everyone benefits from lower rates, but in addition, households have eschewed debt while embracing the safety of Treasuries. Total household liabilities have only increased by 11% since their peak in 2008, according to the Fed. Treasury yields are low because the demand for Treasuries is strong: households now hold over $2 trillion of federal debt, up hugely from $300 billion in 2008. Most of the rest is held by corporate and institutional investors, sovereigns, and foreign investors in general. China alone holds some $2 trillion of Treasury debt.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows why we have come to have a $17 trillion debt. It's simple: government spending has exceeded revenues for just about forever. Note how revenues reliably weaken during recessions and pick up during recoveries. A stronger economy creates jobs, rising incomes, and rising tax payments. Tax receipts thus have a strong cyclical component. One reason for the apparent shortfall in revenues—which began at least a year before Trump's tax cuts—is that the past decade has seen the

weakest growth of any expansion in history.

Chart #6

Spending, on the other hand, is driven largely by transfer payments (medicare, medicaid, social security and income security), which now constitute about 70% of all federal spending (see Chart #6). In the 12 months ended last November, transfer payments totaled $3.2 trillion, while total federal spending totaled $4.5 trillion. No amount of budget cutting is going to make more than a modest dent to federal spending. The elephant in the spending living room is transfer payments, which are paid out according to people's "eligibility," and not according to any Congressional budget appropriations. To control spending will require that Congress change the eligibility formulas for things like social security and medicare.

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows federal spending and revenues as a % of GDP. Here we see that the trends are relatively flat, and the current levels of spending and revenues are not greatly different from what they have averaged since WW II. Revenues do look a bit weak currently, but this is most likely due to the fact that economic growth in the current expansion has been sub-par (2.2% vs. a long-term average of about 3.1%). Revenues haven't picked up much in the current recovery because it has been a weak recovery and because tax rates were cut modestly for individuals and significantly for corporations in 2017. But tax cuts aren't the whole story: revenues weakened at least a year before Trump's tax cuts took effect, and in the past year revenues have been rising at more than a 4% rate. Corporate tax revenues plunged in 2017 and 2018, as expected, but in the first 11 months of 2019 they are up over 10% from the same period in 2018. The Trump tax cuts were a one-time event which was expected to result in much lower corporate revenues initially, to be followed by rising revenues in years to come as overseas profits are repatriated and increased business investment (of which there are few signs to date, unfortunately) results in rising profits in the future.

A digression on debt:

Broadly speaking, debt is a zero-sum game, since one man’s debt is another man’s asset. Debt is an agreement between two parties to exchange cash now with a reversal of that exchange, plus interest, in the future. If the borrower fails to repay his debt (i.e., he defaults), then the borrower benefits by being relieved of some or all of his debt service obligations, and the lender suffers by not receiving some or all of his expected cash flows. Part of the interest the lender charges the borrower goes to offset the risk of default. Most of the time, debt serves a vital economic function by linking savers with borrowers.

Ideally, the lender expects the borrower to use his money to fund a productive investment, such that the return on the investment will exceed the interest on the debt. If all the money loaned to borrowers is invested productively, everyone is happy—borrowers make money and lenders get repaid with interest. The problems with debt come not when people borrow money but when they use borrowed money to make unproductive investments or to simply finance consumption. (It's not the debt, it's the spending, stupid!) It's not clear at all whether using 70% of federal government borrowings to fund transfer payments is a wise use of borrowed money. Taking money from those who are working and giving it to those who are not working creates unproductive and anti-growth incentives.

So it's not crazy to think that much of the federal government's debt has been used unproductively, and this is one reason why our economy's growth rate over the past decade has been sub-par. We've been squandering scarce resources (capital) and creating perverse anti-growth incentives. The potential size of this problem is staggering. In the past decade, after-tax corporate profits have totaled about $16.5 trillion, while federal debt has increased by about $9.4 trillion. In a sense, over half of the profits generated by corporate America have effectively been used to finance federal government spending. If the government hadn't borrowed all that money, it might have been used more efficiently by the private sector. Efficient investment, of course, boosts jobs, incomes, and overall prosperity. Inefficient investment leads to stagnation.

Meanwhile, slow growth has made people more cautious and that has increased the demand for money and people's demand for safety—thus the ready absorption of over $9 trillion of Treasury securities at very low interest rates. The Federal Reserve justifiably has accommodated the increased demand for money and safety by reducing interest rates. So in the current environment, slow growth and low interest rates go hand in hand, and the same conditions that drive low interest rates make lots of debt manageable.

What will happen going forward? If the economy picks up steam, and if tariff wars begin to unwind (as appears to be the case), then money demand should decline, caution should recede, and interest rates should therefore rise. At the same time, a stronger economy would likely result in a further pickup in revenues, a smaller deficit, and slower growth in federal debt. So rising interest rates should go hand in hand with slower growth in total debt even as the burden of debt would tend to rise because of higher interest rates. This is not a recipe for disaster—it's a rosy scenario that we should dearly hope develops!

Chart #8

Meanwhile, nominal and real interest rates are unusually low, which means that the bond market does not yet expect to see accelerating economic growth. In fact, as Chart #8 suggests, the market seems priced to a further slowdown in growth; real interest rates on 5-yr TIPS moved into negative territory this week for the first time since April 2017.

This market is not overly enthusiastic about the future, which gives me comfort that an optimistic approach to risk should be rewarded.

Things to watch for going forward; Real interest rates on TIPS are key barometers of the bond market's expectations for economic growth in the years ahead. If they rise this would be a good sign. Swap spreads are key indicators of the health of financial markets and leading indicators of economic health; right now they are very low and that is very good. Any rise above 30-35 bps on 2-yr swap spreads would be a flashing yellow light. Credit spreads on corporate debt are key indicators of the market's confidence in the outlook for corporate profits; currently they are relatively low and that is good. Commodity prices have been relatively low, but recently they show signs of perking up; if this continues that could be an indicator that the global economic outlook is improving. The residential construction has been in a period of consolidation in the past year or so, but recently appears to be picking up, and that is good. Any slowdown in the growth of bank savings deposits would be a good sign that risk aversion is declining and optimism is rising, and that would be very good.

Looking ahead, I'm optimistic that the economy will continue to grow. I don't see a risk of recession nor do I see any significant acceleration. I'll be watching the aforementioned indicators to see if things improve enough to get really excited.