Monday, February 28, 2011

The big problem with healthcare? It's not a market

I've showed this chart before, but this version includes recently-released data as of 2009.

Markets function well when they are free of outside intervention, when transactions costs are low, and when both parties to transactions have good information on which to base their buy/sell decisions. That is most certainly not the case for the healthcare market, and that's why it's a mess.

Thanks to a distortion introduced to our tax code in the early days of WWII, only employers can deduct the cost of healthcare insurance. To circumvent war-time wage and price controls which were preventing employers from attracting badly-needed workers, the government agreed to allow companies to give workers tax-free health insurance; companies could deduct the cost of the insurance, and it wasn't considered income to the workers. Workers thus received an important tax-free benefit which has since grown enormously in size and importance.

This significant feature of the tax code has finally taken us to its logical conclusion: whereas consumer paid for most of their own healthcare prior to 1940, they now get almost all of their healthcare paid for by someone else, since this is highly tax-efficient. Along the way, of course, politicians have created a baker's dozen of federal and state programs designed to pay other people's healthcare costs.

The system as it stands today works best for employees when the insurance offered by employers and government agencies covers as much healthcare as possible, thus maximizing the tax benefit. That's the reason why low-deductible policies with prescription drug coverage are so popular. If employees were paying for their own healthcare, many would undoubtedly choose higher-deductible policies.

As the chart shows, consumers now pay only 12% of total healthcare costs out-of-pocket. The rest is paid by private health insurance companies (32%), medicare (20%), medicaid (15%) and other private and government programs. The 12% that is still paid out of pocket consists mostly of payments by individuals not covered by employer policies or government programs (whether voluntarily or not), and co-pays and deductibles by individuals that are covered.

It stands to reason that when people don't pay the bill for the services they receive, they are very unlikely to take price into consideration when making a healthcare decision. Why shop around if everything is paid for by someone else? And when politicians set the reimbursement rates for medicare, there is a huge potential for error and fraud. And when insurance companies and government agencies pay most of the bills, even for small things like a vial of 30 pills, back-office costs begin to add up. Furthermore, those who aren't employed by a company that offers healthcare insurance face an immediate "tax wedge" since they must pay for their own insurance with pre-tax dollars, thus inflating the cost relative to someone who is covered by an employer. That extra cost figures importantly in many people's decision to not buy insurance. Add it all up and you have every reason to think that the market for healthcare is not going to be a well-functioning or efficient market. It's not really a market at all, and that's why it's such a mess.

The biggest single way to fix the healthcare market would therefore be to change the tax code. Either let everyone or no one deduct the cost of healthcare insurance. If there were no tax-efficiency reasons for employers to offer healthcare insurance, most would eventually drop the program (it's a headache) and just let employees decide how to spend the money. (Think of the parallel between this and the big shift away from defined-benefit plans in favor of defined-contribution plans) That would put consumers back in charge and I would bet any amount of money that all sorts of healthcare innovations would be unleashed—as healthcare insurers and providers were forced to compete directly for customers—that would eventually result in a more efficient, less-costly, and more satisfying healthcare experience for everyone.

As a corollary, a good portion of the money that is currently being spent by government agencies on healthcare could be turned over to consumers in the form of a voucher. We need to let consumers make the decisions about how to spend the money, not bureaucrats.

UPDATE: For a thorough analysis and review of what's necessary to fix healthcare, see John Cochrane's essay "After the ACA: Freeing the market for healthcare." It's very long, but also very excellent. A must-read for anyone.

Thoughts on the yield curve

These charts tell the long-term story of Treasury yields. Yields today are very low by historical standards, but the yield curve is almost as steep as it's ever been. Yields today are low because inflation is low, and because the Fed—and the bond market—are very concerned about the health of the economy and the risk that a lot of economic "slack" might produce deflationary pressures.

To avoid deflation and to give the economy a boost, the Fed has promised to keep short-term interest rates very low for a long time. The market currently expects the Fed funds rate to remain at 0.25% for at least the rest of this year. Since the yield on 10-yr Treasuries is driven in large part by the expected future path of short-term rates (i.e., the current 10-yr yield of 3.4% implies that the Fed funds rate will average 3.4% over the next 10 years, with the funds rate projected to rise to about 4.25% within 10 years), the Fed's promise to keep short-term rates low for an extended period is putting downward pressure on 2- and 10-yr Treasury yields. But the 10-yr yield is not completely constrained by the Fed's promises—if the bond market were convinced that the Fed was making a big mistake by keeping short-term yields low-for-long, then it would be free to jack up future expected rates.

Regardless, it would appear that 10-yr yields of 3.4% today are fairly valued if inflation stays in a 1-2% range. In other words, there is no evidence here that the fed has grossly distorted the yield on Treasury notes or bonds, since they currently yield about 2% more than inflation, and that is in line with historical observations. And the almost-unprecedented steepness of the 2-10 curve suggests that the market is not giving the Fed much benefit of the doubt: the amount of eventual tightening that is priced in is also almost without precedent. I take this as evidence that the Fed is not unduly distorting yields, and that it is guiding policy more or less in line with current market thinking. Long-time Fed-watchers know that the Fed and the bond market are always engaged in an intricate and complicated dance, where one leads the other and vice-versa. The feedback goes in both directions, and there is no sign that anything is obviously amiss right now.

But if inflation rises and/or the Fed decides to raise rates sooner than expected because the economy is exceeding expectations, then 10-yr Treasury yields will face inexorable pressure to rise. That is the big "if" that is hanging over markets today.

Truck tonnage shows impressive gains

I'm a little late to the Truck Tonnage party (see Mark Perry's latest post on the subject here, and Calculated Risk's post here), but I do have this interesting chart to add to the discussion. Truck tonnage (seasonally adjusted) has now almost completely recovered to its pre-recession highs, after a strong 3.8% gain in January. Say what you will about the Fed inflating asset prices, but when the millions of trucks out there are actually hauling increased amounts of stuff around the country, that's a pretty good indication that economic activity is definitely picking up.

As this chart shows, the stock market has done a pretty good job of tracking truck tonnage over the decades, though it tends to "overshoot" now and then as psychology at times blinds investors to the underlying fundamentals. My read of this plus many other indicators I've highlighted here is that there is a genuine upturn in the economy underway, and the stock market is in the early stages of catching on. With trucking activity poised to reach new all-time highs this year, there is no reason not to expect the equity market to also register new all-time highs.

More strong news from the manufacturing sector

I don't usually pay much attention to the regional components of the ISM surveys (they don't always correlate well to the national survey), but this one is hard to ignore. The Chicago Purchasing Managers Index has soared in recent months, well ahead of expectations. It hasn't been this strong since the boom days of the 1980s, and it's well above the levels recorded during the boom in the second half of 2003, when the economy grew at a 5.2% annual rate. Where there's smoke there's fire, as they say. Although not as strong as Chicago's number, the Dallas Fed and Milwaukee manufacturing surveys for February handily beat expectations. The economy is almost surely accelerating.

Friday, February 25, 2011

Gauging market sentiment -- still very cautious

The equity market has rallied some 25% since the end of last August, with only a few pauses or mini-corrections. Is it now overbought and vulnerable to a major decline? In order to answer that question I look at market-based measures of investor sentiment, which I survey below. I conclude that there is still a good deal of fear, uncertainty and doubt priced into the market. When I then look at the two dozen bullish charts I posted a few days ago, which paint a picture of an economy with fairly solid growth fundamentals, I further conclude that there is little or no reason to worry about a major correction or another bear market at this point. The time to worry about a big downturn in the market is when the great majority of people are convinced it won't happen, and when market-based sentiment indicators are priced to a high degree of confidence in the future. That is not the case today.

As this chart shows, consumer sentiment is on the rise, but from an historical perspective, it is still quite low. Consumers are still wary and worried about the future, even though the economy has recovered to some extent from the recent recession. Why? For one, the federal budget is in terrible shape; and unless big steps are taken to cut discretionary spending and halt the unchecked growth of entitlement spending (e.g., social security, healthcare), we will find ourselves in a world of hurt. Huge deficits, fueled by unchecked spending, threaten the living standards of all those who work, since government spending is inefficient—squandering the economy's resources—and at some point too much spending will result in a permanent rise in tax burdens. Two, the Fed's quantitative easing experiment is a huge foray into uncharted waters, and can only inspire great uncertainty about the future value of the dollar. Three, the across-the-board surge in commodity, energy, and gold prices seems likely to feed through to higher prices at the consumer level. In the face of these three facts, it would indeed be amazing if consumer confidence were at high levels.

Credit default swap spreads have come way down from their recent highs, reflecting a significant improvement in the outlook for the economy. But they are still substantially higher than they were in early 2007, when markets were calm and few questioned the economy's long-term fiscal and economic health.

This chart of the option-adjusted spread on corporate debt goes back farther in time but tells the same story: spreads are much lower today than they were two years ago, but they are still at levels that in the past have signaled impending economic distress, and they are still substantially above the levels that in the past have been associated with relative economic and financial tranquility.

This chart of the Vix Index—the classic measure of the equity market's fear, uncertainty and doubt—has also come down a lot from its recent highs, but it too is still trading at levels that are higher than what we have seen during periods of relative tranquility in the past. It's not significantly higher than what might be considered "normal," but the point I'm making is that it's not at or even close to all-time lows. Nobody today is arguing that the path to the future looks bright and free of risk. On the contrary, the list of things to worry about is long and well-known: federal fiscal profligacy, geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, Fed policy in uncharted waters, a president whose popularity is extremely low, a very weak dollar, soaring gold and commodity prices, and a severely depressed housing market. (Please add to the list as I'm sure I'm leaving something out.) The market, therefore, is still climbing walls of worry, and it shows.

What the Vix Index is to equities, the MOVE index is to Treasury securities: the implied volatility of options on Treasury securities across the yield curve. Like the Vix, this index has come down a lot from the distressed levels of a few years ago, but it is still above levels that in the past have been associated with relative tranquility. In short, the bond market is still somewhat nervous.

This chart shows the ratio of the Vix Index to the 10-yr Treasury yield. High levels of this ratio are a sign of great fear on the part of the market. A rising Vix clearly indicates rising fear, uncertainty and doubt, whereas a falling 10-yr yield is a good indicator that the market is lowering its expectations for economic growth. When the two happen together (thus pushing this ratio higher), it is a sign not only of rising fear but of faltering confidence in the economy. As with many of the other indicators, this one looks much better today than it did a few years ago, but it is still substantially higher than at times when relative tranquility has prevailed.

This chart is one of the few exceptions, since it shows that key measures of financial conditions are at levels that might be considered "normal."

This chart of 2-yr swap spreads is another of the few exceptions, since it suggests that financial market conditions are normal and systemic risk is quite low. A skeptic might argue that swap spreads are low because the Fed is extremely accommodative and by inference prepared to do anything and everything possible to ensure that the economy gets back on its feet and we avoid another banking crisis; by inference, if the Fed were to withdraw its support, things might deteriorate rapidly. That is a fair criticism, but it only bolsters the argument I'm making, which is that the market is not ignoring the risks that lie ahead.

This chart compares the earnings yield on stocks (12-mo. trailing earnings divided by the current share price) to the average yield on long-term BAA-rated corporate debt. It is rare for earnings yields to exceed bond yields, since bond holders are senior in the capital structure to equity owners, and thus have first claim on the earnings. Note that earnings yields exceeded bond yields for several years in the late 1970s, a period that can only be classified as one in which fear, uncertainty, and doubt were extremely high. At the very least, I think this chart provides evidence that the equity market is nowhere near an "overvalued" condition, as—in hindsight—it was at the end of 1999.

This chart is simply the inverse of the EPS (red line) in the previous chart. The point here is that PE ratios are below their long-term average (a sign that investors are unwilling to pay up for a dollar's worth of earnings), and far below where they were prior to the 2000-2001 equity market collapse. Again, it is very tough to argue from this that the market is overpriced or overly-optimistic.

The earnings used in the previous PE calculation are based on reported, 12-mo. reported earnings. In the chart above, I'm using the most recent annualized measure of economic, after-tax corporate profits as reported in the National Income and Products Accounts. NIPA profits are considerable stronger than GAAP profits, and using NIPA profits shows that the market's PE ratio is substantially lower than its long-term average. In fact, it's almost as low today as it was in the early days of the great bull market rally that began in the early 1980s, which, of course, followed a period of great uncertainty and pessimism.

On an inflation-adjusted basis, and relative to a large basket of trade-weighted currencies, the dollar is trading at its lowest level ever. A very weak currency is a classic sign of a lack of confidence in a country. Indeed, the dollar at current levels is signaling that investors worldwide have a great deal of concern about the future of our economy. Contrast this to periods such as the early 1980s and the runup to 2000, when the dollar was very strong, and optimism was widespread.

This chart shows the market's expectation for the level of the Fed funds rate one year in the future. (The last datapoint of 0.42% means that the Feb. '12 Fed funds futures contract is priced to the expectation that the funds rate will average 0.42% during that month.) That the market is only expecting one tightening from the Fed between now and next February reflects expectations that the economy will be struggling to advance for at least the next year. No sign whatsoever of any optimism here.

With the exception of the very first chart above, everything I've shown here is an indicator of market sentiment that is driven by data—not by surveys or anything that might be considered subjective. Although the charts aren't unanimous in their message, on balance I think they at least rule out any suggestion that financial markets are overly optimistic. Indeed, I believe these indicators confirm that that there is still a healthy amount of caution and concern embedded in today's equity prices. For those who believe we can overcome the difficulties that lie ahead, the market would appear to be very attractively priced.

As this chart shows, consumer sentiment is on the rise, but from an historical perspective, it is still quite low. Consumers are still wary and worried about the future, even though the economy has recovered to some extent from the recent recession. Why? For one, the federal budget is in terrible shape; and unless big steps are taken to cut discretionary spending and halt the unchecked growth of entitlement spending (e.g., social security, healthcare), we will find ourselves in a world of hurt. Huge deficits, fueled by unchecked spending, threaten the living standards of all those who work, since government spending is inefficient—squandering the economy's resources—and at some point too much spending will result in a permanent rise in tax burdens. Two, the Fed's quantitative easing experiment is a huge foray into uncharted waters, and can only inspire great uncertainty about the future value of the dollar. Three, the across-the-board surge in commodity, energy, and gold prices seems likely to feed through to higher prices at the consumer level. In the face of these three facts, it would indeed be amazing if consumer confidence were at high levels.

Credit default swap spreads have come way down from their recent highs, reflecting a significant improvement in the outlook for the economy. But they are still substantially higher than they were in early 2007, when markets were calm and few questioned the economy's long-term fiscal and economic health.

This chart of the option-adjusted spread on corporate debt goes back farther in time but tells the same story: spreads are much lower today than they were two years ago, but they are still at levels that in the past have signaled impending economic distress, and they are still substantially above the levels that in the past have been associated with relative economic and financial tranquility.

This chart of the Vix Index—the classic measure of the equity market's fear, uncertainty and doubt—has also come down a lot from its recent highs, but it too is still trading at levels that are higher than what we have seen during periods of relative tranquility in the past. It's not significantly higher than what might be considered "normal," but the point I'm making is that it's not at or even close to all-time lows. Nobody today is arguing that the path to the future looks bright and free of risk. On the contrary, the list of things to worry about is long and well-known: federal fiscal profligacy, geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, Fed policy in uncharted waters, a president whose popularity is extremely low, a very weak dollar, soaring gold and commodity prices, and a severely depressed housing market. (Please add to the list as I'm sure I'm leaving something out.) The market, therefore, is still climbing walls of worry, and it shows.

What the Vix Index is to equities, the MOVE index is to Treasury securities: the implied volatility of options on Treasury securities across the yield curve. Like the Vix, this index has come down a lot from the distressed levels of a few years ago, but it is still above levels that in the past have been associated with relative tranquility. In short, the bond market is still somewhat nervous.

This chart shows the ratio of the Vix Index to the 10-yr Treasury yield. High levels of this ratio are a sign of great fear on the part of the market. A rising Vix clearly indicates rising fear, uncertainty and doubt, whereas a falling 10-yr yield is a good indicator that the market is lowering its expectations for economic growth. When the two happen together (thus pushing this ratio higher), it is a sign not only of rising fear but of faltering confidence in the economy. As with many of the other indicators, this one looks much better today than it did a few years ago, but it is still substantially higher than at times when relative tranquility has prevailed.

This chart is one of the few exceptions, since it shows that key measures of financial conditions are at levels that might be considered "normal."

This chart of 2-yr swap spreads is another of the few exceptions, since it suggests that financial market conditions are normal and systemic risk is quite low. A skeptic might argue that swap spreads are low because the Fed is extremely accommodative and by inference prepared to do anything and everything possible to ensure that the economy gets back on its feet and we avoid another banking crisis; by inference, if the Fed were to withdraw its support, things might deteriorate rapidly. That is a fair criticism, but it only bolsters the argument I'm making, which is that the market is not ignoring the risks that lie ahead.

This chart compares the earnings yield on stocks (12-mo. trailing earnings divided by the current share price) to the average yield on long-term BAA-rated corporate debt. It is rare for earnings yields to exceed bond yields, since bond holders are senior in the capital structure to equity owners, and thus have first claim on the earnings. Note that earnings yields exceeded bond yields for several years in the late 1970s, a period that can only be classified as one in which fear, uncertainty, and doubt were extremely high. At the very least, I think this chart provides evidence that the equity market is nowhere near an "overvalued" condition, as—in hindsight—it was at the end of 1999.

This chart is simply the inverse of the EPS (red line) in the previous chart. The point here is that PE ratios are below their long-term average (a sign that investors are unwilling to pay up for a dollar's worth of earnings), and far below where they were prior to the 2000-2001 equity market collapse. Again, it is very tough to argue from this that the market is overpriced or overly-optimistic.

The earnings used in the previous PE calculation are based on reported, 12-mo. reported earnings. In the chart above, I'm using the most recent annualized measure of economic, after-tax corporate profits as reported in the National Income and Products Accounts. NIPA profits are considerable stronger than GAAP profits, and using NIPA profits shows that the market's PE ratio is substantially lower than its long-term average. In fact, it's almost as low today as it was in the early days of the great bull market rally that began in the early 1980s, which, of course, followed a period of great uncertainty and pessimism.

On an inflation-adjusted basis, and relative to a large basket of trade-weighted currencies, the dollar is trading at its lowest level ever. A very weak currency is a classic sign of a lack of confidence in a country. Indeed, the dollar at current levels is signaling that investors worldwide have a great deal of concern about the future of our economy. Contrast this to periods such as the early 1980s and the runup to 2000, when the dollar was very strong, and optimism was widespread.

This chart shows the market's expectation for the level of the Fed funds rate one year in the future. (The last datapoint of 0.42% means that the Feb. '12 Fed funds futures contract is priced to the expectation that the funds rate will average 0.42% during that month.) That the market is only expecting one tightening from the Fed between now and next February reflects expectations that the economy will be struggling to advance for at least the next year. No sign whatsoever of any optimism here.

With the exception of the very first chart above, everything I've shown here is an indicator of market sentiment that is driven by data—not by surveys or anything that might be considered subjective. Although the charts aren't unanimous in their message, on balance I think they at least rule out any suggestion that financial markets are overly optimistic. Indeed, I believe these indicators confirm that that there is still a healthy amount of caution and concern embedded in today's equity prices. For those who believe we can overcome the difficulties that lie ahead, the market would appear to be very attractively priced.

QE2 update

We're finally seeing the evidence of QE2 show up in the official numbers. The Monetary Base (the part of the money supply that the Fed controls directly) jumped by $140 billion in the most recent period, and is up about $300 billion since mid-Nov. Virtually all of this increase comes from bank reserves which are sitting idle at the Fed (though they do earn an annual interest rate of 0.25%). The increased reserves, in turn, are what the Fed used to purchase Treasuries.

Despite this new injection of reserves, however, there is no evidence to date of any corresponding increase in the other monetary aggregates. That means that although the Fed has created some $300 billion of bank reserves with a keystroke, the amount of money in the economy continues to grow at a rate that is fully consistent with past growth rates. Conclusion: the Fed has not been printing any more "money" than it has in the past.

As the next chart of M2 shows, it has been growing at a 6% annual rate for the past 16 years, during which time inflation has averaged about 2.4% per year. There was a bulge in M2 during the financial panic, but that has since faded away.

What has happened so far with the Fed's quantitative easing program is this: the Fed has swapped newly-created bank reserves (which are the functional equivalent of T-bills) for Treasury notes, and mortgage-backed securities. This has had the effect of shortening the maturity of the government's debt (a good thing since interest rates are low and the yield curve is steep, but it could prove to be a bad thing if and when interest rates start rising), and it has pumped up the Fed's balance sheet by some $1.4 trillion, but it hasn't pumped up the broader supply of "money" in the economy any more than usual. That's not to say it won't happen, only that so far it hasn't happened. We can therefore conclude that, to date, the banking system has been content to hold more risk-free bank reserves and less of other, more risky securities. Similarly, the world economy has been either unwilling and/or unable to increase aggregate borrowing. Put yet another way, the world has been content to hold the extra reserves the Fed has created.

When the Fed's supply of reserves is equal to the world's demand to hold reserves, than there is no inflationary consequence; that explains why inflation has remained relatively low. But there is no guarantee that the situation won't or can't change in the future. It would not be surprising if Fed weren't able to withdraw all the extra reserves in a timely fashion once the banking system decides it no longer wants those reserves. This is the other shoe that is waiting to drop.

Thursday, February 24, 2011

Thoughts on gold and oil

If gold (top chart) can't manage a new high despite soaring crude oil prices (bottom chart) and a chaotic situation in the Middle East, it would appear that gold has already priced in a whole lot of bad news (e.g., geopolitical turmoil and rising inflation). That in turn leaves gold very vulnerable to even the slightest whiff of good news. Caveat emptor.

Credit card delinquencies decline sharply

With a HT to Mark Perry (a good source for otherwise-obscure but important economic facts), I'm posting this chart of credit card delinquencies, which uses data compiled by the Fed. My chart covers a longer period than Mark's (using all the data available), and I think it's worthwhile noting that the current delinquency rate (4.2%) is lower than the average of the past 20 years (4.6%) and lower even than the average of the pre-2008 recession period (4.4%). Consumers are deleveraging and they are also getting their financial health back, however painful this process has been.

Update: A reader's question prompted me to add the next chart, which shows credit card chargeoff rates. It strikes me that a customer typically becomes delinquent before the bank writes off his loan; a bank is not going to write off the loan until it is clear that a customer can't or won't pay. And indeed, the charts suggest that delinquency rates peak prior to the peak in chargeoff rates. Delinquencies look like they peak around the end of a recession, while chargeoff rates peak about 6-12 months after a recession. So that suggests that delinquency rates are a leading indicator of chargeoff rates. The picture becomes a little clearer: we see some significant improvement over the past year, and it would appear that things are going to continue to improve, at least from the banks' perspective.

Capital spending remains strong

January capital goods orders fell by a much-bigger-than-expected 6.9%, but you can't take that number at face value. December orders were revised upwards by almost 3%, and the first month of every calendar quarter has a strong tendency to show declines that are reversed in subsequent months. Using a 3-mo. moving average solves the seasonal problem, and that's what the chart shows: orders continue to increase. In fact, on a year-over-year basis (which avoids seasonal problems altogether), orders are up 14%, and that's a very strong showing. Much stronger, for example, than what we saw coming out of the 2001 recession. Strong investment spending reflects growing business confidence, and it also sows the seeds of future productivity gains.

Continued improvement in weekly claims supports equity prices

Unemployment claims continue to decline in a fairly impressive fashion. I take this as a sign that businesses have worked very hard to cut costs and trim their labor force; most of the layoffs that were required by the economy's new reality (a housing and financial market bust) have already happened. This sets the stage for a resumption of healthy growth, which should become apparent in the months to come. Below is the same chart I posted yesterday, updated with today's numbers. The message is the same: improving economic fundamentals provide strong support for equity prices.

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

Unemployment claims and equity prices

This is an intriguing chart, inspired by one created by macrofugue. (HT Abnormal Returns)

It's a relationship that just makes common sense (e.g., declining claims reflect a healthier economy and a healthier economy drives equity prices higher). Nevertheless, the fact that the equity market has responded quite faithfully to changes in the economic fundamentals goes a long way to refuting the bears' claim that equity prices have been driven higher by easy money, that the economy remains plagued by deep-seated problems, and it is all a house of cards ready to collapse. To me it has seemed rather obvious that the equity market rally has been driven all along by news of improvement in the economy, and declining unemployment claims is just one manifestation of that improvement.

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Rising oil prices are a headwind, but not yet a disaster

Energy prices are timely, especially now that Libya's Qaddafi has ordered the destruction of some oil pipelines to the Mediterranean. Libya produces some 1.9 million barrels of oil per day, or about 2.2% of world oil consumption. That's not a huge amount, but if Libyan supplies are cut off it could prove difficult for Europe and it could contribute to higher world prices, and prices have already jumped 10% since last Friday in anticipation. These charts help put things in perspective.

Oil and gasoline prices are closing in on their 2008 highs, but still have a ways to go—it will take another 40-50% before we see new all-time highs. Gasoline prices in the U.S. are running a bit ahead of crude prices, as suggested in the third chart, but not by that much.

The big question is whether prices are or will soon be high enough to shut down the global economy. I don't think this is an immediate concern. In real terms, energy prices are still well below their previous highs, and the U.S. economy is still on a trend whereby it consumes less energy per unit of output ever year. In real terms, the U.S. consumer spends much less of his/her income—about 30% less—on energy today than in the early 1980s, even though real oil prices today are about 10% higher than they were in 1981.

Higher oil prices would be more problematic if the Fed were tightening monetary policy to keep inflation. As it stands, the Fed is quite accommodative, which means they are supplying enough money to accommodate most or all of the rise in oil prices. If the Fed weren't so accommodative, then higher oil prices would be much more painful because they would require that other prices decline by an equal amount.

Two dozen bullish charts

Back in late August I had a post called 20 bullish charts. It was meant to counteract all the concerns at the time that the U.S. economy was headed for a double-dip recession, caused in no small part by the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. In retrospect, my timing couldn't have been better, since equity markets have rallied strongly since their lows at the end of August.

As we now face another source of concern with the political turmoil in the Middle East and rising oil prices, I thought it might be helpful to review those same charts plus a few others. As should be evident, the fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong, and this is good reason to expect that the economy will continue to push ahead in spite of the headwinds it faces.

Business investment rose 16% last year. Strong capex spending points to growing confidence on the part of business, and that is a leading indicator of future growth in the economy.

Industrial production is rising all over the world. Adverse weather resulted in a modest slowdown in U.S. production in recent months, but production was up 8% in the Eurozone last year, and 5% in Japan. There is still plenty of idle capacity in world manufacturing that can be put to work quickly and cheaply as demand rebounds.

Commodity prices continue to rise across the board, though agricultural commodities appear to have hit a speed bump the past few days. Rising prices reflect strong growth in global demand and/or accommodative monetary policies worldwide. Whatever the case, rising commodity prices all but preclude a bout of debilitating deflation, and rule out the existence of a double-dip recession.

Global trade continues to expand. U.S. exports surged at a 17.6% annualized pace in the second half of last year.

Credit spreads have been reliable leading indicators of recessions in the past, and tighter spreads usually signal improving economic conditions. U.S. credit spreads are now at their tightest levels since the end of the recent recession, confirming that economic fundamentals continue to improve. Swap spreads are good indicators of systemic risk and leading indicators of future economic and financial conditions. U.S. swap spreads have been quite low and stable for the past six months, an indication that U.S. financial fundamentals are about as healthy as they can get. Europe remains troubled, however, but Euro swap spreads are not high enough to signal anything more than the likelihood that there will be some form of sovereign debt default in Europe before this is all over, and even should that happen, it is not likely to bring down the Eurozone economy.

The slope of the Treasury yield curve has been an excellent leading indicator of recessions and recoveries for many decades. The curve typically flattens or inverts in advance of recessions, but today it is still very far from being flat or inverted—indeed, by some measures the yield curve today is almost as steep as it has ever been. The curve is strongly upward-sloping, which reflects easy money and expectations that monetary policy will eventually need to tighten significantly as the economy improves. We've never seen a recession develop when the curve was this steep and monetary policy was this easy. On the contrary, current curve conditions strongly suggest a continuation of economic growth.

China and almost all emerging market economies are growing like gangbusters, and global trade is recovering nicely. What's good for emerging market economies is good for everyone, since the more they produce the more they can buy from us.

As we now face another source of concern with the political turmoil in the Middle East and rising oil prices, I thought it might be helpful to review those same charts plus a few others. As should be evident, the fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong, and this is good reason to expect that the economy will continue to push ahead in spite of the headwinds it faces.

Business investment rose 16% last year. Strong capex spending points to growing confidence on the part of business, and that is a leading indicator of future growth in the economy.

Industrial production is rising all over the world. Adverse weather resulted in a modest slowdown in U.S. production in recent months, but production was up 8% in the Eurozone last year, and 5% in Japan. There is still plenty of idle capacity in world manufacturing that can be put to work quickly and cheaply as demand rebounds.

Commodity prices continue to rise across the board, though agricultural commodities appear to have hit a speed bump the past few days. Rising prices reflect strong growth in global demand and/or accommodative monetary policies worldwide. Whatever the case, rising commodity prices all but preclude a bout of debilitating deflation, and rule out the existence of a double-dip recession.

Global trade continues to expand. U.S. exports surged at a 17.6% annualized pace in the second half of last year.

Credit spreads have been reliable leading indicators of recessions in the past, and tighter spreads usually signal improving economic conditions. U.S. credit spreads are now at their tightest levels since the end of the recent recession, confirming that economic fundamentals continue to improve. Swap spreads are good indicators of systemic risk and leading indicators of future economic and financial conditions. U.S. swap spreads have been quite low and stable for the past six months, an indication that U.S. financial fundamentals are about as healthy as they can get. Europe remains troubled, however, but Euro swap spreads are not high enough to signal anything more than the likelihood that there will be some form of sovereign debt default in Europe before this is all over, and even should that happen, it is not likely to bring down the Eurozone economy.

According to the ASA Staffing Index, demand for temporary and part-time workers is steadily increasing; compared to this time last year, temp hiring is up almost 14%. Gains of that magnitude are fully consistent with an improving economy.

Auto sales have surged at a 16.6% annualized pace since hitting bottom in Feb. '09. This strongly suggests further growth in the economy, and it reflects very favorably on consumers' confidence and financial health. Car sales have consistently exceeded expectations for at least the past year, and that means that manufacturers are continuing to ramp up production targets, and that in turn leads to ripple effects throughout the economy. What's good for Detroit is good for the country.

Large-scale corporate layoffs ended almost a year ago. That means corporations have done most or all the belt-tightening they are likely to do. Businesses are lean and mean, and profits are very strong. Further improvement in the economy is thus very likely to result in more hiring.

It's rare for the economy to stumble when corporate profits are rising. Profits are now at record levels, both nominally and relative to GDP, so it's very likely the economy will continue to grow. As a result of very strong profit performance, corporations are sitting on over $1 trillion in accumulated profits. That could provide a tremendous amount of fuel for future investment, economic growth, job gains, and income gains.

Although the Vix index (a proxy for the degree of fear and uncertainty that the market is pricing in) has jumped to 21 today, as of yesterday financial conditions were essentially "normal" according to the Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index. Normal financial market conditions are fully consistent with a healthy and growing economy.

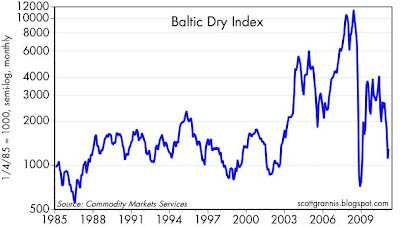

A significant increase in new cargo ships has depressed shipping costs for bulk commodities (as reflected in the Baltic Dry Index), but the Harpex Index of shipping costs for N. Atlantic containerships continues to rise.

The equities of major home builders have been relative stable for the past year, suggesting that the housing market bust has run its course. With new construction far below what is needed to keep pace with a growing population, residential construction activity will sooner or later start picking up significantly as housing inventories are depleted and consumers return to the market. Meanwhile, prices for commercial and residential real estate have been roughly flat for almost two years. This is the sort of action you would expect to see as a market that has been severely overbuilt and distressed slowly consolidates.

This chart of commercial mortgage-backed security prices lends strong support to the notion that the real estate crisis has passed and underlying conditions are actually improving quite a bit. Distressed sales and fears of a deflation/depression pushed these AAA CMBS prices down as low as 55 at the peak of the crisis, but they have since rebounded to just over 97. Why? Because defaults have been far less than was once feared. This chart also points to significant unrealized gains on the books of banks and institutional investors who were forced to write off significant amounts as the prices of securities collapsed, but have yet to declare the subsequent gains in the securities they held on to (i.e., profits at many firms are likely understated).

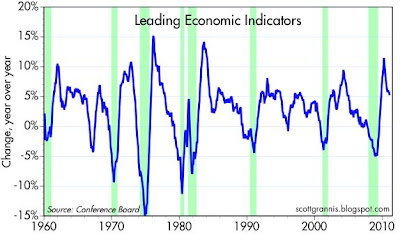

The leading indicators continue to point to growth. Nothing here to suggest even a whiff of impending weakness.

Federal revenues have been rising at a 10% annual rate for the past year. This is an excellent sign of economic health, since it reflects rising incomes, rising capital gains, and rising corporate profits.

The M2 measure of money supply has been growing about 6% per year on average for a long time. That it continues to do so means that a) there is no shortage of money in the economy and b) the Fed's Quantitative Easing program has yet to result in any unusual increase in the amount of money circulating through the economy. In turn, the latter suggests that there is no reason yet to fear a burst of inflation or an unexpected tightening of monetary policy that could threaten the economy's ability to grow. Although I and many others continue to worry that QE2 will prove inflationary, the jury is still out. Meanwhile, the Fed has managed to expand the supply of money by enough to satisfy the increased, fear-related demands for it, thus avoiding any risk of deflation.

Last but not least, manufacturing conditions according to the Institute for Supply Management are very healthy, suggesting that GDP growth in the current quarter could easily be 4-5%. Moreover, since last August we see that conditions in the much larger Service Sector have improved significantly. To top things off, both the manufacturing and service sector surveys reflect substantial improvement in new hiring activity.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)