The stock market is making new all-time highs, even as the bond market is getting crushed; 10-yr Treasury yields are up almost 100 bps since their all-time low in early July. Industrial commodity prices are on a tear, yet the U.S. dollar is gaining against almost all currencies. These seeming contradictions (Aren't higher rates supposed to be bad for the economy? Don't commodity prices usually move inversely with the dollar?) aren't a portent of doom, they're more likely symptomatic of an improving global economic outlook, led by the U.S. economy.

President-elect Trump appears to be a catalyst for the recent surge in stock prices and the dollar, since the market is right to be encouraged by the prospect of lower tax rates and less burdensome regulations if Trump gets his way (ignoring for the moment his terribly misguided trade bombast). But Trump doesn't get all the credit: the healthy trends underway today began way before Trump was even close to becoming president. As I pointed out some

four years ago, and which is now clearer than ever, the Obama years have had one very positive result from the perspective of economists. They have been the equivalent of a laboratory experiment designed to answer the question "Can government spending stimulate the economy?" For decades economists have debated the value of the government spending multiplier (i.e., how many extra dollars of GDP does one dollar of additional government spending create?). Keynesians have generally argued that the multiplier was greater than one, while supply-siders have generally argued it was less than one. We now know for sure that it is less than one, and it could very possibly be negative. More government spending most probably means less economic growth.

As I argued back then, the ARRA was a disaster:

American taxpayers borrowed $840 billion only to learn that the payoff was a small fraction of the additional debt incurred. We wasted almost a trillion dollars of the economy's scarce resources, and that's a big reason why the recovery has been so disappointing. If we had instead "spent" the money on lowering tax rates for everyone (e.g., we could have eliminated corporate taxes for three years with the ARRA money spent) in order to give them a greater incentive to work and invest, the results could have been dramatically better. The tax cuts might even have paid for themselves in the form of a stronger recovery over time.

And its effects have lingered, giving us the

weakest recovery on record. As I

noted over two years ago, federal deficits effectively absorbed all the profits of U.S. corporations since the latter half of 2008:

Despite assurances from politicians and most economists of Keynesian persuasion, not only did the biggest and most rapid increase in our federal debt burden since WW II fail to boost the economy, it coincided with the weakest recovery in history—growth of only 2.2% per year on average. (I was among those who warned in late 2008 that this would happen, and quite a few times over the years following.) This is not a problem of not spending enough, it is a failure of ideology, and arguably the most expensive such failure in the history of the world.

In short, most of what U.S. businesses have managed to produce in the way of profits in the current business cycle expansion have been borrowed by the federal government only to be flushed down the Keynesian toilet. Starved of basic investment nutrients, the economy has been weak and the public is frustrated. A weak economy—which today is some $3 trillion smaller than it might have been with better policies—is the

measure of our discontent. Weak growth is the root cause of people's frustration with trade, and the reason the recent election was all about spurning the ruling elite, who think that they can pull the policy strings and magically create growth and prosperity. Most people figure they could be working more productively, and they'd rather have a better job than more government handouts. Among other things, Hillary Clinton made the mistake of promising free college and a higher minimum wage to a public that instinctively understood that there is no free lunch.

The other really big thing that has affected the economy for years, and yet is generally misunderstood, is monetary policy, and more specifically Quantitative Easing. Most people think that QE was all about artificially lowering interest rates in order to stimulate the economy. But how is it that the Fed has purchased more than $3 trillion worth of notes and bonds since 2008, yet there has been no appreciable impact on growth or inflation?

The Fed is complicit in the public's misunderstanding, since it has falsely represented QE as "stimulus." In fact it was not stimulus at all: it was accommodation. The 2008 financial collapse struck such fear into the heart of the markets and investors that risk aversion and strong demand for money and other safe assets has been the predominant driver of market sentiment ever since. Last year I

recapped this argument, noting that "QE was not about pumping money into the economy, it was all about satisfying the economy's demand for liquidity. QE was erroneously billed as "stimulative," since printing money in excess of what's needed only stimulates inflation. Instead, QE was designed to accommodate intense demand for money, without which the economy might well have stumbled." The proof is in the pudding: despite years of an unprecedented expansion of the monetary base, inflation remains relatively low. If the Fed had truly been "printing money" we would have seen much higher inflation by now. The Fed supplied the money the market needed, and interest rates fell because the economy could not manage to deliver anything resembling normal growth.

Going forward, this means that we must watch very carefully whether and by how much the public is regaining confidence and becoming less risk averse. As I've said quite a few times in recent years,

the return of confidence is the Fed's worst nightmare. More confidence and less risk aversion would almost surely go hand in hand with reduced demand for money and safe assets in general. If the Fed doesn't take timely steps to offset a reduction in the demand for money (by reducing the supply of excess reserves and increasing the interest it pays on excess reserves), then inflation could come back with a vengeance.

So now we know that 1) government "stimulus" spending doesn't stimulate, especially when accompanied by rising tax and regulatory burdens, and 2) monetary "stimulus" didn't

stimulate growth, since all it did was accommodate a risk averse public with an enormous appetite for safe assets. This understanding will help us track whether President Trump is making things better and whether the Fed is going to keep the dollar strong and inflation low.

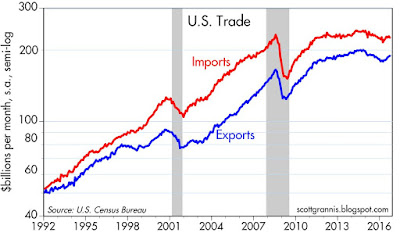

Trade policy will be very important as well, since free trade is undeniably good. Yet, thanks to Trump, free trade unfortunately has gotten a bad rap in recent years since it has been blamed for the loss of millions of jobs. Fortunately, David Malpass is a key figure in Trump's economic policy team, and I've known him for many years. He's a solid supply-sider, with plenty of public policy experience and a deep appreciation for markets. He fully understands the importance of free trade. Yesterday the WSJ

excerpted some of his recent remarks on economic policy issues. On the subject of Nafta (North American Free Trade Agreement), David makes it clear that the problem with Nafta is not that it has made trade free, but that it has made trade less free:

I was there at the beginning of Nafta. The idea of Nafta was, it was supposed to be…a very clear, free-market orientation that would allow both sides of the border to do what they do best in the classical sense of more commerce.

But as it was negotiated, year after year, special interests descended upon it. And it got thicker and thicker and thicker. This was 1989, 1990 and into 1991. It’s up to 1,200 pages and then [President George H.W.] Bush left, [President Bill] Clinton came in and added the environmental chapter and the labor chapter.

It became this monstrously large, managed trade process that doesn’t work at all for small businesses in the U.S…. There are too many parts of it that are not working.

In other words, he wants to make "free trade" freer, not less free. This is very encouraging. If lower and flatter taxes and less regulation can boost the economy (and I'm sure they can), I'm confident that with David's help, Trump can renegotiate existing trade agreements in order to make them more free, and that in turn will help boost the economy. A stronger economy will then help absorb the millions of workers who lose their jobs to overseas competitors. To sum up: the problems associated with free trade today stem from the fact that 1) trade hasn't been as free as it should have been, and 2) the economy has been too weak to create new jobs to replace the ones lost to more efficient overseas markets.

If Trump ignores Malpass, preferring to slap punitive tariffs on China rather than negotiate better and freer trade agreements, then this won't help at all. We'll have to keep a close watch on this.

What follows are updated charts which illustrate these themes and how they are progressing.

The chart above illustrates how fear, uncertainty and doubt about the economy's strength have sparked every one of the market's downturns in recent years. The recent decline in the red line has been driven by a decline in the Vix index (the fear index) and a sharp rise in 10-yr Treasury yields (one measure of the market's confidence in the future strength of the economy). As each of these panic attacks have faded, the market has gone on to higher levels.

The CRB Metals index is up 40% over the past year, and it is up "yuge" regardless of which currency it is measured against. This strongly suggests that global economic activity is picking up.

I doubt many people are aware of this fact: excess bank reserves have fallen over 25% from their high of a few years ago. The Fed has been conducting a stealthy and sizable reduction in the amount of reserves that banks could use to exponentially increase their lending—and the money supply—if they so chose. This is an under-appreciated good development.

The current PE ratio of the S&P 500 is 20.5, according to Bloomberg, which means that the earnings yield on stocks (the inverse of the PE ratio) has fallen to just under 5%. PE ratios are meaningfully above their long-term average of 16, but the earnings yield on stocks is still significantly higher than the yield on 10-yr Treasuries (see chart above). When stocks are priced so that they yield a lot more than risk-free Treasuries, it's a good bet that the market deeply distrusts the ability of corporate earnings to sustain their current levels. (Since stocks generally have expected returns that are higher than risk-free returns, a "normal" state of affairs would have earnings yields equal to or lower than risk-free yields.) In other words, the fact that the equity risk premium is still quite positive is a good sign that risk aversion is still the order of the day in the equity market, although risk aversion does appear to be declining on the margin.

Not surprisingly, consumer confidence is only modestly above its long-term average, as the chart above illustrates. Confidence has been improving on the margin, but it is still far from what we might term exuberant.

The chart above compares the prices of gold and 5-yr TIPS (using the inverse of their real yield as a proxy for their price), both of which are considered to be "safe" assets. Gold is a classic refuge from all sorts of uncertainties, and TIPS are not only risk-free but also protected against inflation. Both have been declining on the margin, and that is a good indicator that confidence is rising and risk aversion is declining. But prices are still quite elevated from an historical perspective.

The chart above suggests that the current level of real yields on 5-yr TIPS is consistent with an expectation that real economic growth is going to be somewhere in the neighborhood of 2 - 2 ½% going forward. That's better that the growth we've seen over the past year, but still a far cry from the robust growth we enjoyed in the late 1990s. If 5-yr TIPS yields get back up to 2% I'm going to be very excited about the prospects for the U.S. economy.

The two charts above illustrate the dramatic increase in money demand over the past two decades. The amount of "money" (as defined here by M2, which is the sum of currency in circulation, time deposits, checking accounts, retail money market funds, and bank savings deposits) relative to national income has never been so high. Relative to long-term trends, there is arguably as much as $2 trillion of "extra" money in the economy today, which is another sign that risk aversion is still a big deal. Most if not all of the increase in M2 has come from an increase in bank savings deposits, which still pay almost nothing. People are holding almost $9 trillion in bank deposits these days, preferring their safety to the much higher yields available on riskier assets.

Over the past 8 years M2 has been increasing at an annualized rate of 7-8%, while nominal GDP has been increasing at about a 4% annualized rate. Relative to the size of the economy, the amount of money being held by the public has increased by over 50%. If the public should ever want to reduce its holdings of so much money, what might happen? Bear in mind that wanting to hold less money doesn't mean that money just disappears. I can reduce my holdings of money, but only if someone else increases theirs. Should the public on balance want to hold less money relative to incomes, the only way that can be accomplished is by increasing the nominal size of the economy. In short, wages and prices would have to rise if the public wants to reduce its money balances.

There's a lot of money out there that could wind up bidding up the prices of goods and services if the public were to fully regain its confidence in the future. That's a lot of inflation potential to worry about, but it only becomes a concern if confidence rises and the Fed fails to take offsetting measures (e.g., raising short-term interest rates by enough to keep the demand for bank deposits from declining). Call it the Trump Paradox, in which good news could turn out to be bad news if the Fed flubs its job.

Stay tuned.