Real GDP declined for two quarters straight, and most would agree that meets at least one condition for a recession call. I would prefer to call it a Recession Lite.

Over the course of the first six months of the year, real GDP declined by 0.63%. On an annualized basis, that works out to -1.25%, which by the standards of past GDP revisions (which can easily be on the order of ±1-2%), is arguably statistically insignificant. But it does seem clear that the economy is in a bit of a funk, most likely due to high inflation, so it would be fair to say we are (once again) experiencing Stagflation.

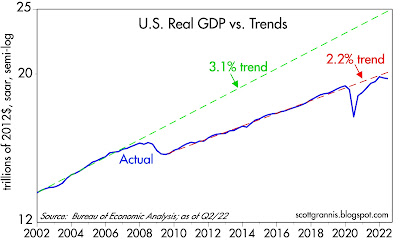

Chart #1

Chart #1 is my contribution to understanding what's going on with the economy. I don't think you'll see this anywhere else. Let me first note that the y-axis is logarithmic, which makes steady growth rates look like a straight line. The blue line is inflation-adjusted GDP, in 2012 dollars (the dollar was worth about 22% more back then than it is now). The green line shows what the path of GDP would have been if the 40-yr trend from 1966 through 2007 were still in place (during which period the economy grew on average about 3.1% per year). The red line shows the 2.2% annual trend which has held since mid-2009.

Today the economy is only about 2.2% below its most recent trend, but it is a gigantic 26% below its long-term trend. The big question we should be asking is why the economy is so far below a trend that persisted for 40 years and which suddenly disappeared following the Great Recession. Demographics likely played a role (an aging population), and globalization likely resulted in the export of lots of traditional jobs to other countries. But those factors don't change overnight—they change over many years. So I'm more inclined to point the finger at politics: increased regulatory burdens, huge deficit spending, and rising tax burdens, all of which create headwinds to growth.

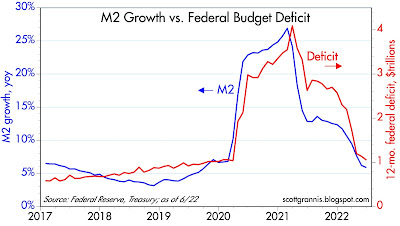

In any event, this year's modestly disappointing economic growth hardly justifies dramatic changes in policy. Since the inflation we are suffering today has its roots almost exclusively in massive deficit spending in 2020 and 2021, the last thing Congress should do is spend more money that must be borrowed (or, perish the thought, printed). And since incentives to work, invest, and take risk are the lifeblood of productivity, the last thing Congress should do is raise taxes on anyone, since higher taxes reduce the incentives to work, invest, and take risk. And since any good economist knows that businesses don't pay taxes, Congress should not even consider raising the corporate income tax rate. If a business is taxed more it must pass the tax burden on to its shareholders, employees, and customers—otherwise it will go out of business. Taxing business is just an indirect—and very inefficient—way of taxing everyone.

Joe Manchin, are you listening? That deal you just signed on to violates economic reason.

Recession Lite seems like an apt descriptor for today's economy, because a lot of the ingredients of a true, painful recession are missing. Jobs are growing by leaps and bounds (about 400K per month so far this year!), job losses are low, job openings are at stratospheric levels, industrial production is rising, capital spending is rising, the volume of world trade is at a new high, the stock market is recovering, and Covid-19 is yesterday's news.