A Fed rate cut along the lines the market is calling for will not strengthen the economy. Easier money can never generate growth all by itself, but easier monetary conditions can make it easier for the market to cope with adverse conditions. Smooth-running financial markets are an essential ingredient to the health of the economy. Right now, financial market conditions are an impediment to growth, and the Fed can and should remove that impediment by acting soon.

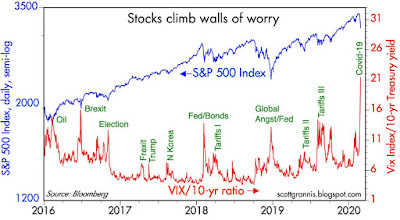

Chart #1

As Chart #1 shows, 10-yr Treasury yields have fallen to new, all-time lows—currently 1.17%. 5-yr Treasury yields are now just under 1%, a level last seen/exceeded only during the panic surrounding the PIIGS and Brexit crises (2011-2013).

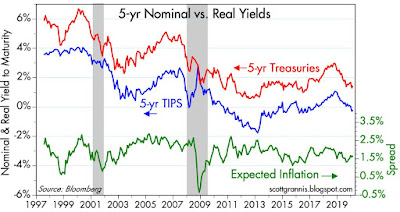

Chart #2

Chart #2 is the best way to judge whether the Fed is keeping short-term rates too high. The red line (5-yr TIPS yields, which are the market's expectation for what the real Fed funds rate (the blue line) will average over the next 5 years, has recently fallen below the current real Fed funds rate by about 50 bps (the 5-yr TIPS yield is -0.44%, and that is about 50 bps below the difference between the current Fed funds target, 1.75%, and the current Core PCE inflation rate, which is about 1.7%). In short, the market now thinks the Fed is "too tight." The pricing of Fed funds futures shows that market fully expects the Fed to cut rates by 50 bps within the next few months. Given the panic, the sooner this happens the better.

Chart #3

Chart #3 shows the prices of gold and 5-yr TIPS (using the inverse of their real yield as a proxy for their price). Both have surged of late, reflecting the market's strong desire for safe and safe-haven assets.

The Fed can't provide a cure for the Covid-19 virus, but it can mitigate its adverse effects by easing monetary conditions in response to the market's increased desire for money and money equivalents. Doing so is simply doing the Fed's principal job, which is to maintain a balance between the supply of money and the demand for it. Right now the Fed is not doing enough, and we can see that in the fact that inflation expectations have fallen by roughly 25 bps in the past 10 days, to a relatively low 1.4%, as shown in Chart #4.

Chart #4

P.S. Be sure to check the updates to my last post for insights into the degree to which the market has panicked.

UPDATE: as of March 4. Yesterday the Fed did indeed cut rates by 50 bps, but there is still some pressure from the market for at least one more cut and likely two. In light of the majority of comments I see in the press to the effect that the Fed pulled a "shock and awe" move, and that it might be running out of ammunition, I feel the need to reiterate that the Fed's move has nothing to do with "stimulating" the economy or an otherwise positive "shock" to sentiment. It's simply a recognition of market realities.

The current real (inflation-adjusted) Fed funds rate is about -0.45%. But the current real yield on 5-yr TIPS (which is essentially the market's forecast for what it thinks that rate will average over the next 5 years) is -0.60%. Thus the market expects the Fed to cut at least once more and/or inflation to rise a bit from current levels.

It may also be the case that the very low level of interest rates on short-term securities like TIPS and T-bills is the market's way of telling the Fed that there is a shortage of such securities. Perhaps the Fed should consider increasing the level of excess reserves. The press would shout "another round of quantitative easing!" but in reality it would just mean accommodating the market's desire for more T-bill equivalents (bank reserves are in effect T-bill equivalents). The Fed can expand reserves by buying notes and bonds and paying for them with reserves, just as it did in three QE episodes. When the demand for reserves is intense, as it is now, transmogrifying notes into T-bill substitutes is not inflationary, nor is it necessarily stimulative. It's just supplying more short-term securities to the market to satisfy the demand for such. That would presumably allow the financial markets to function more smoothly, and that, in turn, could make it easier for the economy to deal with the uncertainties of the Corona virus

UPDATE: as of market close March 5th: The Fed is almost certain to cut rates by at least another 50 bps. Chart #5 provides the rationale:

Chart #5

I've long argued that the Fed usually follows the market. Chart #5 shows partial proof. The orange line is the 3-mo. T-bill rate, and the white line is the upper bound of the Fed's funds rate target. Note that in the early stages of Fed tightening (2015-2017), the Fed tended to lead the market: T-bill rates moved up several months after the Fed raised its target. But since 2019 the Fed has been following market rates on the way down. T-bill rates were always ahead of the Fed, and each ease was merely an attempt to bring the funds rate in line with T-bills. Since Tuesday's cut of 50 bps, T-bill rates have plunged. This suggests the Fed will need to cut rates by at least 75 bps just to keep up with the market!

When the Fed cuts rates in order to follow the market down, this is NOT monetary ease. It's NOT stimulus. It's NOT money printing. It's passive monetary policy. The big story is NOT Fed easing. The big story is the market's insatiable demand for safe and liquid securities. The virus-induced panic has caused a tremendous increase in the demand for money and money-equivalents, which are now demonstrably in short supply. The Fed MUST accommodate this demand by lowering its target rate and by increasing the supply of bank reserves (i.e., QE4).