For weeks I've been struggling to come up with a post that puts recent events and trends into a coherent perspective. It's been difficult, however, since for every positive there seems to be a negative. Optimism here, pessimism there. Good fundamentals (e.g., great liquidity, very low credit and swap spreads, very low weekly claims, strong confidence numbers, lots of job openings) alongside obvious signs of economic weakness (e.g., trade wars negatively impacting global trade, very low real interest rates, slowing jobs growth, an inverted yield curve, a big slowdown in earnings growth, weak manufacturing surveys, and most recently, slowing GDP and corporate profits growth). The stock market seems optimistic about the future (it just keeps going up), but the bond market is priced to slow growth for as far as the eye can see. Neither market is priced to unreasonable assumptions.

At best, I can say that the outlook for economic growth is Ok—not great, but not terrible either. Maybe more of the same: 2-3% real growth. Lower tax rates have not yet created boom-time conditions. Business investment has been disappointing. Overlooked, however, is the significant

reduction in regulatory burdens that the Trump administration has been able to achieve. It's hard to quantify this, but we haven't seen anything so positive in this area since just about forever. If Trump's tariff wars can be resolved (by drastically reducing are eliminating tariffs), the economy has lots of upside potential.

What follows is a random collection of 14 charts and comments:

Chart #1

Q2/19 growth (see Chart #1) came in above expectations, and the level of real GDP in Q1/19 was revised upwards a bit as part of the yearly revision to prior years. But the distribution of growth over the past 4-5 years changed, with the result that the economy was a bit stronger a few years ago than we thought, and in recent quarters it has been a bit weaker. The media was quick to note that downward revisions to 2018 growth rates robbed Trump of his claim to have delivered 3% real growth (it is now estimated to have been 2.5% instead of the previously reported 3%). Still, the economy has definitely picked up from its 2016 slump, when year over year growth fell to 1.3% in Q2/16. The current expansion is now just over 10 years old, and it has registered an annualized growth rate of 2.3%.

Chart #2

Chart #2 is my now-famous "GDP gap" chart, updated for the latest GDP statistics. The current economic expansion remains by far the weakest in history, with annual growth averaging only 2.3% instead of the 3.1% that prevailed from the mid-60s to the mid-00s. For the first time ever, the economy failed to reattain its long-term growth trend following the last recession. The "shortfall" in growth now amounts to $3.4 trillion by my calculations. Maybe we'll never reattain that long-term trend—who knows? But if nothing else, the chart demonstrates just how much lost income can accrue from a modest reduction in long-term trend growth rates. If this had been a typical recovery, the economy today would have been at least $3-4 trillion bigger. That translates roughly to just over $10,000 per person of "lost" annual income.

Chart #3

As Chart #3 shows, real yields on 5-yr TIPS are trading just under 30 bps. As the chart suggests, that implies that the market's estimate of the economy's current trend rate of growth is about 2.4% per year, which is somewhat less than what we have seen in recent years. The bond market, in other words, is priced to a continuation of the kind of growth we have seen over the past 10 years. Expectations of a Trump boom have all but evaporated. That may be too pessimistic, in my view, but it's not all that terrible either: just more of the same so-so growth. On the bright side, there's virtually no sign of what might be considered "overheating." No growth boom might well mean less chance of a growth bust.

Chart #4

Chart #4 compares the year over year growth rate of the economy to the year over year growth rate of private sector jobs. Not surprisingly, the two tend to track each other. More jobs translate into a bigger economy. But note the gap between the two lines, which is roughly equivalent to labor productivity. When the economy grows faster than the growth of jobs, it can only mean that workers are becoming more productive. We've seen a mini-boom in productivity under Trump's leadership, but it has faded in the past 6-9 months, and it is nowhere near as strong as we have seen at times in the past. It's disturbing

that this is occurring just as the growth of private sector jobs has slowed meaningfully (see my

last post for the numbers). Undoubtedly it is these sorts of numbers which have put the bond market in a pessimistic mood.

Chart #5

Today's GDP figures included revisions to past data going back 4-5 years. One of the most significant changes was to corporate profits, which were reduced in the past 1-2 years by almost one percentage point of GDP (with most of that being added to incomes). Yet despite that significant reduction, corporate profits remain historically strong, well above their long-term average relative to GDP.

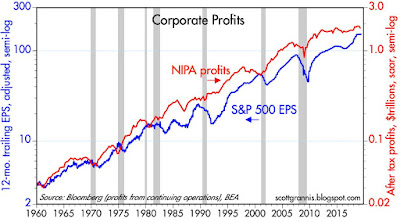

Chart #6

Chart #6 compares the two major measures of corporate profits: one, according to the National Income and Product Accounts (blue line), and the other according to reported earnings per share. The former includes all businesses, while the later includes only those that are publically held. The recent downward revisions to NIPA profits have substantially reduced the gap between the two measures. (Note that the y-axis for both measures uses the same ratio between high and low values—thus the growth rates of both measures have been substantially similar since 1960.) Note also that the growth of both measures has subsided quite a bit over the past year or so. Reported EPS are up by a mere 1.3% annualized rate over the past six months, and NIPA profits have registered no net growth over the previous year.

Chart #7

Does the big slowdown in profits growth mean the stock market is overvalued? Not necessarily, as suggested by Chart #7. The current PE ratio of the S&P 500 is just under 20, which is only 18% above its long-term average. We've seen big PE "bubbles" in the past, but the current uptick in PE ratios is more in the nature of a blip than a bubble. And it's quite consistent with the prevailing level of Treasury yields, as we will see in Chart #9.

Chart #8

Since NIPA profits and the EPS measure of profits are tracking each other pretty closely these days, it's fair to use NIPA profits as a proxy for EPS, which is what Chart #8 does. NIPA profits have the advantage of being seasonally-adjusted, quarterly annualized figures, whereas EPS typically are reported using the last 12 months of earnings. NIPA profits are thus more timely, and they may be more accurate since they reflect true economic profits, thanks to adjustments for inventory valuation and capital consumption allowances. This exercise produces results which are not greatly different (although less volatile) from those of Chart #7. Both measures of PE ratios currently tell the same story: equity multiples are above their long-term average, but they are not excessive.

Chart #9

The line in Chart #9 is the result of taking the earnings yield on the S&P 500 (which is equivalent to the dividend yield on stocks if all companies paid out all their earnings each quarter) and subtracting the yield on 10-yr Treasury bonds. Investors currently are willing to give up about 300 bps of earnings yield in order to hold 10-yr Treasuries (conversely, it means that investors demand an extra 300 bps of yield in order to hold equities instead of 10-yr Treasuries). From a price-multiple perspective, the PE ratio on 10-yr Treasuries is 48, which is almost 2 ½ times higher than the PE ratio on the S&P 500. That tells me the market is pretty pessimistic. Numbers like these only make sense if you assume the market expects corporate profits to decline meaningfully in the future, and for there to be little if any improvement in the economy's health in coming years.

Chart #10

Long-time readers of this blog know that I interpret monetary policy from a strictly monetarist perspective. When the supply of money exceeds the demand for money, money loses value and inflation goes up. Conversely, deflation occurs when the supply of money is less than the demand for money. Big swings in inflation invariably prove harmful for growth. The best monetary policy, in my book, is the one that maintains a low and stable rate of inflation. That alone is all the "stimulus" an economy needs. The Fed can't create growth out of thin air, but it can provide a growth-enhancing environment for an economy.

I focus on the Fed's willingness to supply money and money equivalents and how that compares to the market's demand for same. I don't consider the Fed's decisions to raise or lower interest rates to be necessarily restrictive or stimulative. A reduction in short-term rates (which implies an increase in the supply of money) might actually be harmful if the demand for money is rising at a faster rate. Last May I

argued that the Fed needed to reduce rates in response to an increase in the demand for money. Not because the economy was on the cusp of a recession, and not because it needed a shot of stimulus, but because to not do so would imply a tightening of monetary conditions at a time when pessimism was the order of the day, and that might eventually lead to uncomfortably low inflation (or deflation) and/or a recession.

So Chart #10 is important to keep in mind. What it shows is that the demand for money (using the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP as proxy) soared in the wake of the Great Recession. Subsequently, money demand fell from mid-2017 to mid-2018 as confidence soared and the economy strengthened, and it has creeped back up in the past few quarters, as tariff wars and slowing global growth have brought risk aversion back into fashion. Quantitative Easing was necessary to satisfy the economy's demand for money; it was not full-bore stimulus as many seem to think. The dollar's relative stability and the persistence of relatively low and stable inflation are proof that the Fed wasn't "printing money." That's still the case today. I continue to believe the Fed is justified in reducing short-term interest rates, which they will likely do at next week's FOMC meeting. This won't necessarily be "stimulative" but it will reassure markets and keep liquidity conditions healthy.

Chart #11

Chart #11 looks at one very important financial variable, namely 2-yr swap spreads (which are briefly

explained here). Currently, swap spreads in both the US and the Eurozone are low. This is a very good sign, since it implies that liquidity is abundant and financial conditions are generally quite healthy. Liquid financial markets are essential to a well-functioning economy, just like shock absorbers are essential for a smooth ride. Swap spreads have also tended to be good predictors of future economic health. Swap spreads today tell us that systemic risk in most major economies is quite low, and that the economic outlook is therefore positive.

Chart #12

Chart #13

Charts #12 and #13 are some of the most troubling charts in my collection. Manufacturing conditions have deteriorated significantly in the past 6-9 months, both here and in Europe. Not surprisingly, we now know that real growth also slowed over that period. Fortunately, while conditions remain relatively weak, they are not bad enough (so far) to imply an impending recession. Especially considering the ongoing health of the service sectors.

Chart #14

Chart #14 looks at the service sectors of the US and Eurozone. Here we see that conditions have not deteriorated to the same extent as they have in the manufacturing sector (the US service sector is orders of magnitude larger than the manufacturing sector). The relative health of the service sector undoubtedly reflects the fact that Trump's ongoing tariff wars are directed almost exclusively to the manufacturing and goods-producing sectors of global economies.

Tariffs are disruptive, there's no question about it. We need to get rid of them as soon as possible. When and if that happens, confidence is likely to return and economies are once again likely to flourish.