I first visited Argentina in 1970, when I spent my summer there visiting my soon-to-be wife. The country has intrigued, fascinated, and frustrated me ever since. In 1975 we decided to move there and I've been an avid student of monetary policy and inflation ever since. In 1976 we witnessed the military overthrow of the disastrous government of Isabel Perón. After a few years of "relative" stability under a military dictatorship, things began to deteriorate about a year or two after we returned to the States in 1979. Our timing couldn't have been better. By the late 1980s, Argentina was spinning out of control, as its annual inflation rate peaked at over 20,000%. During a visit to the country around that time I was fascinated to watch hyperinflation unfold: prices almost tripled within the span of three weeks. Miraculously—or so it seemed—inflation subsequently fell to zero by the mid-1990s, thanks to the government's decision in 1991 to peg the peso at 1-1 to the dollar.

During the four years we lived in Argentina, inflation averaged about 7% a month. That adds up to an annual inflation rate of 125%, and that's enough to seriously impact your everyday life. My first memory of when the reality of inflation hit me was the day I collected my first paycheck. I began thinking "what should I do with this money?" Keeping the money in my pocket or under the mattress made no sense, since the money was losing value constantly—because prices were rising constantly. The decision was easy: we had to spend the money, and spend it fast. So my wife and I set off for the nearest warehouse store to buy "stuff" that we could store in the closet. Canned foods and powdered milk for our 1-year old infant ranked high on our list. We scoured the store and found a bunch of storable stuff, but we couldn't find any milk. I thought that was curious, because it was very popular (Leche Nido, by Nestle). But then I opened a door to an adjacent storage room and saw boxes of powdered milk stacked to the rafters. So I asked the girl at the cash register if someone could fetch us a couple of boxes. "I'm sorry, sir," she replied. "The milk is not for sale."

That's when it dawned on me that everyone was thinking like I was: nobody wanted money, everyone wanted stuff instead. For the next several years I would juggle money balances between pesos and dollars and "stuff." With lots of inflation, money becomes like a hot potato. When I saw something for sale that I needed and the price looked reasonable, I would buy it immediately, because I learned that if you waited to look for it in another store, the price was likely to go up. During one episode of very high inflation, grocery stores would post prices on chalkboards, and change them throughout the day. It was a daily struggle to survive, because salaries and wages always went up after the prices for "stuff" went up (incomes lagged prices, and over time that impoverishes wage earners).

In 1979 we sold our house, in preparation for returning to the U.S. There was no such thing as a mortgage at that time, and hardly anyone had a checking account. If you wanted to buy a house, the best terms you could find were "0-30-90," which meant that you had to pay one-third of the purchase price at the time of signing the purchase contract, followed by the second third a month later and the final third in three months. The man who bought our house (for the equivalent of about $30,000) graciously agreed to pay me the full amount in cash at the signing of escrow. Before going to the escrow office to finalize the deal, we went to his office. There he took out several grocery bags full of peso bills and started counting the bills; after counting each stack he passed it over to me, and I counted it, then he placed the stack back in one of the bags. I wish I could remember what the price of the house was in pesos, but all I remember is that the bills were of large denomination and they filled three grocery bags—it took us a half hour to count it all. After we had both counted the money and signed the escrow papers, he accompanied me to the bank to help me carry all the money and to serve as an informal body guard—can you imagine carrying cash equal to the price of a house in grocery bags while walking 6 blocks to the bank? I handed over the bags of money to the cashier and explained that I wanted to convert the pesos to dollars and wire the total amount to my account in the U.S. It took the cashier 20 minutes to count and verify the bills. I was fortunate that at the time it was legal to convert pesos to dollars and to wire dollars to an overseas bank account—it hasn't always been like that, and it isn't today.

When we visited Argentina in 1986, I remember my 6-year-old son was fascinated by all the banknotes that people carried around in order to conduct their daily transactions. They had denominations ranging from 3 to 8 digits. Prices were routinely quoted in "palos" with a palo being slang for a million, much as we would say "5 bucks." A friend gave my son a grocery bag full of old peso notes that he had collected, and he went almost crazy with delight. "Wow, Dad, how much can I buy with all this money?" he asked me. "Well, Ryan, with all that money you might be able to buy a pack of chewing gum," I replied, even though the nominal value of the notes must have been in the tens of millions. I then tried to explain to him how inflation worked, but I quickly realized he just couldn't understand it.

Years later I would study the situation in Argentina during the time we lived here and understand what was happening. In a nutshell, since the government was unable to finance its deficit by selling bonds, it simply ordered the central bank to print up new currency in order to pay its bills. New bills flooded the country like Monopoly money. Money became like a hot potato that nobody wanted to hold. Better to change my peso salary to dollars at the beginning of the month, and then convert back to pesos when I needed to buy something. Better to save money by buying stuff than to save money in the bank. Since very few people back then had bank accounts, newly-minted bills just kept accumulating in the economy and losing their value. A $1 million peso note issued in 1978 was initially worth several thousand dollars, but by the mid-1980s that same note was worth only 20 cents and was withdrawn from circulation.

Bottom line, the supply of pesos was growing rapidly at the same time that the demand for pesos was falling. This resulted in a huge increase in money velocity (which is equivalent to saying there was a huge decline in the demand for money), and the ratio of money to nominal GDP fell sharply for years and years. A 50% increase in the money supply could support a 70 or 80% rise in prices and nominal GDP. The government would periodically try to slow the rate of inflation by limiting money growth to a rate lower than the prevailing rate of inflation, but it never worked because the velocity of money just kept increasing. More and more people held their money balances in dollars instead of in pesos, and spent their pesos as fast as they could. The government was essentially financing its deficit via an inflation tax; as long as you were holding pesos in your hands, they were losing value and you were effectively paying money to the government. So everyone naturally tried to avoid holding pesos. It was a vicious circle, as rising inflation destroyed confidence and the demand for money, and that in turn fueled higher inflation.

The key feature of the U.S. monetary system—as distinct from Argentina's—is that the Fed cannot create money directly—only banks can do that. The Fed can, however, make it easier for banks to create money by increasing the supply of bank reserves. Banks need reserves in order to collateralize their deposits. The Fed creates reserves by buying securities (e.g., Treasury bills, notes and bonds, and more recently, mortgage-backed securities and some corporate bonds). In effect, the Fed buys securities and pays for them with bank reserves. But crucially, reserves are not money that can be spent anywhere.

In times of great uncertainty and surging money demand, like today, the Fed fills the market's need for short-term safe securities by buying riskier securities from the banking system and paying for them with risk-free reserves which pay a floating rate of interest; reserves thus have become T-bill equivalents. If banks don't find the reserves attractive they can use them to support increased lending, which indeed does result in a monetary expansion. But if that expansion exceeds the market's demand for money, then higher inflation will be the result. Throughout most of last year, the fact that inflation did not rise strongly suggests that the Fed's actions were not inflationary. Bank reserves—which swelled by about $4 trillion last year—served to satisfy the banking system's demand for risk-free, short-term assets, and the public's demand for a massive increase in bank savings deposits and checking accounts. Demand for money and money equivalents was turbo-charged last year by all the uncertainties and disruptions caused by the Covid-19 panic.

But now things are changing. Uncertainty is declining, and confidence is increasing. People don't want or need to hold so much money in the form of bank savings deposits. Prices for many things are rising, and measured inflation has accelerated significantly. The Fed argues that the rise in inflation is only transient, the result of lockdown-induced supply shortages coupled with exuberant demand from newly "liberated" consumers who no longer worry about Covid. The Fed also argues that "easy money" is necessary to help the economy back on its feet. I disagree.

In times of great uncertainty and surging money demand, like today, the Fed fills the market's need for short-term safe securities by buying riskier securities from the banking system and paying for them with risk-free reserves which pay a floating rate of interest; reserves thus have become T-bill equivalents. If banks don't find the reserves attractive they can use them to support increased lending, which indeed does result in a monetary expansion. But if that expansion exceeds the market's demand for money, then higher inflation will be the result. Throughout most of last year, the fact that inflation did not rise strongly suggests that the Fed's actions were not inflationary. Bank reserves—which swelled by about $4 trillion last year—served to satisfy the banking system's demand for risk-free, short-term assets, and the public's demand for a massive increase in bank savings deposits and checking accounts. Demand for money and money equivalents was turbo-charged last year by all the uncertainties and disruptions caused by the Covid-19 panic.

But now things are changing. Uncertainty is declining, and confidence is increasing. People don't want or need to hold so much money in the form of bank savings deposits. Prices for many things are rising, and measured inflation has accelerated significantly. The Fed argues that the rise in inflation is only transient, the result of lockdown-induced supply shortages coupled with exuberant demand from newly "liberated" consumers who no longer worry about Covid. The Fed also argues that "easy money" is necessary to help the economy back on its feet. I disagree.

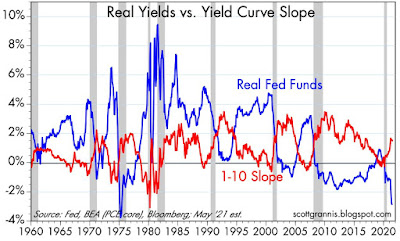

I think the Fed is making a big mistake by pegging short-term interest rates at a level that is far below the current rate of inflation. Holding cash or cash equivalents (e.g., bank savings deposits, checking accounts, T-bills, money market funds) pays virtually zero interest, just as holding actual cash does. But holding cash in your pocket or at the bank means you are losing money—you are effectively paying an inflation tax which amounts to as much as 8% per year (the CPI rose at an 8.45% annualized rate in the three months ending in May).

Let that sink in. Your money balances are costing you 8% per year. Cash is not a safe asset these days. It's a very expensive asset, in fact. Better to get rid of cash by spending it on almost anything else, right? Buy land, buy powdered milk, buy stocks, buy commodities, fix up your home, buy a car, invest in new plant and equipment ... the list goes on, and not surprisingly, the prices of all those things are rising. It's Argentina deja vu all over again. Oh, and in addition to shedding unwanted cash, you might also consider borrowing money in order to buy things, since the cost of borrowing is less than the rate of increase in the prices of those things.

Current Fed policy amounts to a concerted effort to undermine the demand for money, at a time when the supply of money continues to surge. The M2 money supply has risen at a 15.4% annualized rate in the six months ending in May, and it's up at a 15.1% annualized rate in the three months ending in May. That's a classic prescription for rising inflation. For the two-decade period leading up to the Covid period, M2 growth averaged a little over 6% per year—and for that same period inflation was relatively low and stable.

It gets worse. The Fed is not just targeting a near-zero rate for short-term securities that is far below the current level of inflation, it is all but ensuring that the rate on short-term securities will continue to be far below the rate of inflation for at least the next two years—and possibly for as far as the eye can see. The market is in full agreement: the implied yield on 3-mo. LIBOR two years from now is 0.8%, which implies about 2 Fed tightenings in the interim. In fact, the entire Treasury yield curve, from 1 day out to 30 years, falls well below the current rate of inflation. The TIPS market provides further proof that interest rates are expected to be below the level of inflation for as far as the eye can see: 5-yr real TIPS yields are -1.6%, 10-yr real yields are -0.9%, and 30-yr real yields are -0.2%.

Who wants to hold Treasuries that will produce negative real returns for a lifetime? Who wants to hold cash that will lose up to 8% of its value in the next year? The longer real yields remain negative, the more the incentive to reduce one's holdings of cash and other "risk-free" securities, and the more the incentive to increase one's holdings of "stuff" that will on average appreciate by the rate of inflation.

Economics is all about scarcity and incentives. Today the incentives are powerfully lined up to fuel a cycle of rising inflation. People respond to incentives, and they are voting with their feet. That's why the prices of things are rising, and that's why rising inflation is very unlikely to be a transient problem. Unless, of course, the Fed reverses course and begins jacking up short-term interest rates in a BIG way. Which in today's political environment seems unlikely.