The chart above compares the actual growth of real GDP (blue) with its long-term trend of about 3% per year. Never before has real GDP fallen below its trend by so much for so long—and still, as we are about to enter the sixth year of recovery, there is no sign of a true recovery. The current "gap" between actual GDP and its long-term trend is about 10% by my calculations. That translates into a national income shortfall of roughly $1.7 trillion.

This is the measure of the country's discontent: $1.7 trillion in missing income.

The chart above compares the actual growth of a subset of retail sales (which excludes certain volatile categories) to its long-term trend. These are the expenditures made by ordinary folk, not the mega-billionaires. This helps dramatize just how radically things changed beginning in the latter half of 2008. Retail sales by this measure would have to increase 16% overnight to get back on their long-term trend path. This is the measure of how much middle class families are hurting.

After growing for decades at about a 1% annual pace, the labor force suddenly stopped growing in late 2008, as the chart above shows.

If one thing stands out in these charts, it is the abruptness and the severity and the persistence of the divergence from long-term trends that began in 2008. Something REALLY BIG happened; what was it?

It was not demographics, since demographics change at glacial speed. The population didn't suddenly got older and start to retire en masse in late 2008.

It was not monetary policy. The Fed was arguably slow to launch its QE efforts in late 2008, but since then they have been working overtime to make sure the economy is not starved of liquidity and interest rates are as low as possible. (I could be persuaded that the persistence of extremely low interest rates has been a problem for savers, and that this has led to weak investment, but corporate profits have been setting records throughout the recovery.)

The one thing that changed in a really big and durable way, starting in 2008, was fiscal policy. The Bush administration launched TARP in late 2008, and the Obama administration followed up with ARRA in 2009. Then came Obamacare in 2010, which purported to restructure fully one-sixth of the US economy within the space of a few years. Then came the Dodd-Frank super-regulation of the financial industry. Beginning in 2013, top marginal tax rates were increased.

As the first of the above two charts shows, massive fiscal "stimulus" increased the federal government's debt from $5.34 trillion in June '08 to $12.45 trillion as of this week. As the second chart shows, that surge of borrowing doubled the federal debt burden, raising it from 36% of GDP to 72% of GDP in a mere four and a half years. The only other time something of this magnitude happened with fiscal policy was WW II.

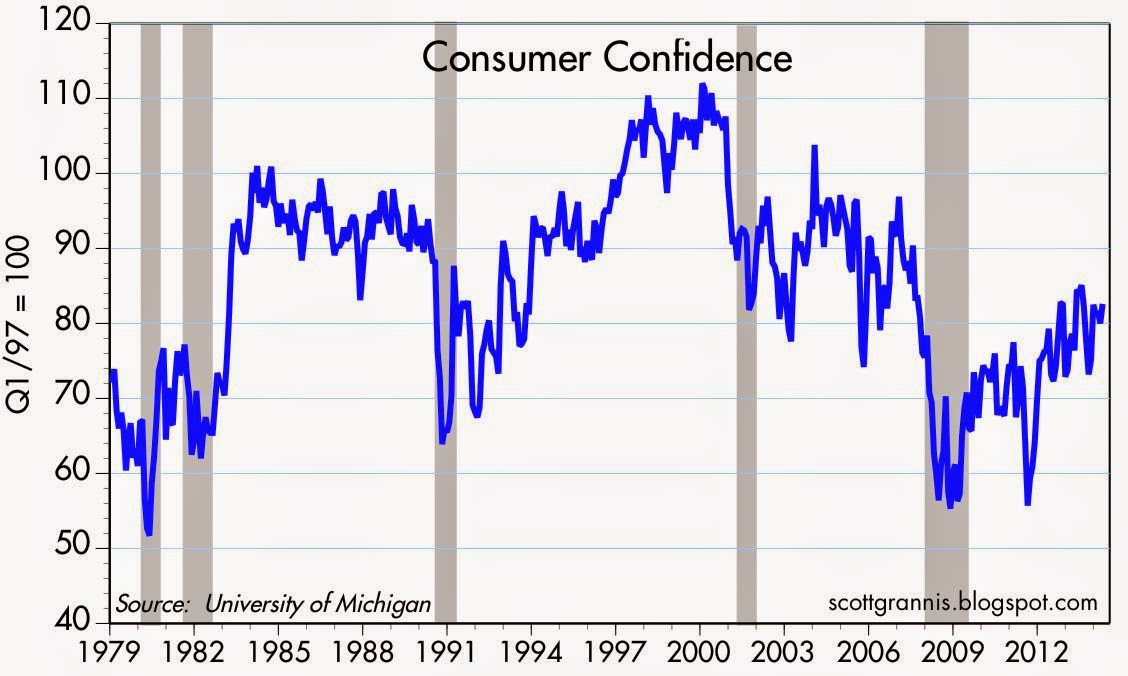

The federal government borrowed $7.1 trillion over the course of five and a half years and handed most of the proceeds out in the form of various transfer payments. Our leaders in Washington did this in the belief that this would stimulate spending and that would convince businesses to create more jobs. The federal government restructured the entire healthcare industry in the belief that this would lower costs and give everyone healthcare insurance coverage. The federal government rewrote the rules for the entire financial industry, in the belief that a more-highly-regulated banking system and greater consumer protections would restore confidence and optimism. And to top it off, the federal government increased taxes on the rich, in the belief that this would benefit the middle class by more fairly distributing the fruits of progress. But it didn't work. Spending wasn't stimulated; job growth didn't surge; healthcare costs continue to rise, the vast majority of the uninsured are still uninsured, and millions are now losing what coverage they used to have; banks are reluctant to lend and consumers are reluctant to borrow; consumer optimism remains relatively weak; and the middle class has taken it on the chin.

If anything, the massive growth of government intervention in the economy since 2008 looks to be the Occam's Razor explanation for what caused the weakest recovery in history.

If there is a reason for widespread discontent, it is our federal government and its overbearing and intrusive ways. Thanks to all the government "help" that has been heaped upon us in the past six years, we have the weakest recovery in history. And the bill for all this is a staggering $1.7 trillion per year and counting.