A quick update on M2, GDP, and interest rates:

There is still a "surplus" of M2 money, but it is shrinking every month. Higher interest rates have boosted the demand for money, in effect neutralizing the declining M2 surplus. We know this because all indicators point to a significant decline in inflation, especially when measured at the margin (year over year growth rates can be very misleading when important changes in trends are occurring). High interest rates discourage borrowing (banks expand the money supply by lending), encourage saving and discourage spending (holding onto all that M2 keeps it from getting spent).

Inflation is not driving interest rates higher—the Fed is. Real interest rates on TIPS have surged to levels not seen since before the Great Recession. This is a sign of monetary tightness, as is the recent weakness in gold prices, the strength of the dollar, and well-grounded inflation expectations. It may also be a sign that the market has become more confident about the outlook for the economy. There's one thing that has the market worried, however, and that's the risk that the Fed will keep on pushing rates higher than they need to be.

Inflation is not driving interest rates higher—the Fed is. Real interest rates on TIPS have surged to levels not seen since before the Great Recession. This is a sign of monetary tightness, as is the recent weakness in gold prices, the strength of the dollar, and well-grounded inflation expectations. It may also be a sign that the market has become more confident about the outlook for the economy. There's one thing that has the market worried, however, and that's the risk that the Fed will keep on pushing rates higher than they need to be.

The BEA today released revised GDP statistics going back many years. Real (inflation-adjusted) GDP is now measured in 2017 dollars (before it was 2012 dollars), and the revisions show it has been growing a bit faster since 2009 than we thought (before it was 2.1% per year, now it's 2.2% per year). The much-feared recession (I've lost track of the many recession forecasts that have fallen by the wayside over the course of this year) has yet to appear, and I still see no signs that it is imminent or likely in the near future.

Chart #1

As Chart #1 shows, M2 has fallen by almost 4% since its peak in the summer of last year. The "gap" between M2 and its long-term trend growth of 6% per year since 1995 has now shrunk by half and looks set to continue shrinking. When M2 first surged there was no increase in inflation because the demand for money in the first phase of the Covid lockdowns was intense—fear was rampant, and it was difficult to spend all the money that was being showered on the public in the hopes it would forestall a depression. But as the economy began to open in early 2021, the demand for money began to fall and that fueled a surge in inflation—demand for goods and services outstripped the supply. The Fed failed to react to this dynamic at first, (saying inflation was just "transitory") but then began tightening in earnest in early 2022.

Chart #2

Chart #2 is evidence that the surge in M2 was caused by excessive, debt-fueled government spending. M2 surged just as the federal deficit surged. Declining deficits removed the source of M2 growth beginning in early 2021. We are fortunate that the second surge in deficit spending, which began about a year ago, has not resulted in any increase in M2. Deficits are no longer being monetized. Thank goodness. And so far, there has been no return of Covid panic.

Chart #3

Currency in circulation comprises about 10% of M2. As Chart #3 shows, currency growth also surged in the wake of Covid, only to retreat. The excesses of the Covid era are fading.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows the growth of real GDP (blue line) as it compares to two different trend rates of growth (green and red). From the 1960s until 2007, real GDP grew on average by about 3.1% per year. Following the Great Recession, it has only grown by about 2.2% per year. What caused such a huge change? I think it is the result of 1) excessive government regulation and spending, 2) higher tax burdens, and 3) increased social welfare spending (transfer payments). Whatever the cause, the economy has experienced sub-par growth for over two decades. Things are unlikely to improve unless we reverse the causes of sub-par growth, and that's not about to happen anytime soon.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows the quarterly annualized rate of growth of the GDP deflator, which is the broadest and most timely indicator of inflation available. During the second quarter of this year, prices throughout the economy rose at a mere 1.7% rate, well below the Fed's professed target. Memo to Fed: pass this chart around the office!

Chart #6

Chart #6 looks at the level of 5-yr real and nominal yields, and the difference between them (green line), which is the rate of inflation the market expects to prevail over the next 5 years. Inflation expectations are well grounded, and have fallen in the past year or so—thanks to the Fed's decision to jack interest rates up. One important conclusion thus appears: interest rates are higher not because of inflation fears, but because of the Fed's actions. And the Fed's actions appear to be driven meaningfully by mistaken worries that the economy might prove to be too strong and thus inflation might remain too high. Balderdash: the economy is still experiencing sub-par growth even as inflation has plunged. Growth didn't cause inflation, deficit spending that was monetized did, and it's not happening anymore.

UPDATE (Sept. 29):

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows the 6-mo. annualized change in the Personal Consumption Deflator and its Core (ex-food and energy) version, both of which were released this morning. The former is a broader measure of inflation than the CPI, and its weightings change dynamically as the economy changes (not so with the CPI, which is why it is a flawed measure). It is up at a 2.6% annualized rate. The latter is the Fed's favorite measure of inflation, and it is up at a 3.0% rate; but on a 3-mo. annualized basis, it is up only 2.2%. Inflation is rapidly approaching the Fed's target—why can't they acknowledge this? Why is the market so nervous?

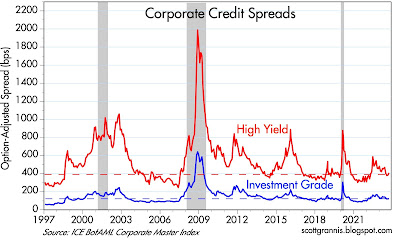

Chart #8

Chart #8 shows credit spreads for investment grade and high-yield corporate debt, as of yesterday. By any measure, credit spreads are relatively low, and that implies a healthy economic outlook. There is no sign whatsoever here of an impending recession. This chart also directly refutes the idea—apparently embraced by our addled Fed—that economic weakness is necessary to bring inflation down. Since inflation peaked in mid-2022, investment grade spreads have fallen from 171 bps to 123 bps, and high yield spreads have fallen from 600 bps to 409 bps. Both of those declines imply a much-improved economic outlook at the same time as inflation was falling from 8-9% to less than 3%.

39 comments:

Thanks Scott! I really enjoy reading your analysis! Best regards from Belgium 🇧🇪

Hi Scott.

Thanks as always.

ELI5 - what's an example of non-monetized deficit spending? I'm trying to wrap my head around any sort of deficit spending doesn't drive inflation.

Variant, re deficit spending: Throughout most of our history, the federal government has financed spending in excess of revenue by selling bonds. Doing this creates no money, because the government is simply taking money from the public in exchange for bonds.

Monetizing deficits is very different, and Argentina is the perfect example. Since the Argentine government has no credibility, it is essentially unable to borrow money via legitimate channels. Instead, it simply asks the central bank to "lend" it money that the central bank simultaneously creates. Simply put, the central bank prints money and then gives it to the government, which the government then uses to pay its bills. This results in a continual and massive expansion of the money supply and high and rising inflation. Anyone accepting the government's "monopoly money" immediately begins losing his or her purchasing power. Inflation becomes a means by which the government acquires purchasing power from the public.

This is not to say that our government did the same things during the Covid years, but it can be demonstrated that about $6 trillion of "emergency" spending coincided with a $6 trillion increase in M2 between 2020 and 2021. Somehow (no one has been able to describe exactly how it happened) the Fed allowed the US money supply to increase by an amount that almost exactly matched the size of the federal deficit.

Of course it's bad enough that we have a FED which thinks inflation is due to economic strength/too many people working, but the silence is deafening about the recent avalanche of downward revisions in GDP and employment data.

"Somehow (no one has been able to describe exactly how it happened) the Fed allowed the US money supply to increase by an amount that almost exactly matched the size of the federal deficit."

I had noticed this statement in an earlier post. Can anybody figure out how this happened?

It has certainly caused a lot of pain to the average Joe (as usually happens when a large, powerful government manipulates markets). It did provide an excellent investment opportunity in certain asset classes in late 2020-~2022.

Thanks for the post.

great post!

Thanks for the amazing post

Scott,

Plse explain how to measure the change in inflation ,,at the margin" vs a typical way of mesuring it.

Re “at the margin”. When an economy transitions from high inflation to low inflation, or vice versa, the change in trend will first appear in observations that compare the current price level with one 3 and 6 months prior. Using a year over year comparison, which most people seem to favor, tends to minimize the changes that are occurring over recent time periods. Most of my charts that focus on inflation use 6-month annualized rates of change, but I also like to see what 3-month annualized rates of change are as well. So by “on the margin” I mean recent changes, not long-term changes.

Chart 4 showing the dramatic decline in GDP after 2008 and the most concrete connection between policy change and enormous impact on a population. While the 3 reasons you stated are definitely bad policy, are they the primary cause? I thought the cause of in GDP growth was the Fed policy change to a surplus reserve model. The Fed funds rate has, since 2008, been almost meaningless. Paying banks to hold reserves rather than lending them out means capital is not deployed efficiently, thereby lowering GDP growth.

Tom: By paying interest on reserves, the Fed does not preclude banks from lending. Indeed, an abundance of reserves means that banks have an almost unlimited capacity to lend. To the extent that bank lending has been less than super-charged, this means simply that the demand for loans (which is the flip side of the demand for money) has been weak (i.e., money demand has been strong, thanks to high interest rates).

Regardless, I am not a fan of the Fed’s ability to set short-term interest rates at the level which maximizes growth while also minimizing inflation. That is an almost impossible task, and one that the Fed has failed at repeatedly in the past. Fed mistakes have been the cause of almost all recessions in my lifetime.

re: "the dramatic decline in GDP"

Bernanke destroyed the nonbanks by remunerating IBDDs. The nonbanks shrank by 6.2 trillion dollars while the banks grew by 3.6 trillion dollars.

The remuneration rate on IBDDs, interbank demand deposits, exceeded all short-term interest rates as far as 2 years out in 2011 (which was illegal per the Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006).

And contrary to the pundits, banks don't lend deposits. Dr. Philip George almost gets this right in his "The Riddle of Money Finally Solved".

The economy is being run in reverse. Lending/investing by the DFIs expands both the volume and the velocity of new money. Lending by the NBFIs increases the turnover of existing deposits (a transfer of ownership), within the commercial banking system.

It is much more desirable to promote prosperity by inducing a smooth and continuous flow of monetary savings into real investment, than to rely, as we have done c. 1965 (with the advent of interest rate manipulation as the FED’s monetary transmission mechanism), on a vast expansion of bank credit with accompanying inflation to stimulate production.

According to Corwin D. Edwards, professor of economics,

[Edwards attended Oxford University in England on a Rhodes scholarship and earned a doctorate in economics at Cornell University. He spent a year teaching at Cambridge University in England in 1932. He taught at New York University in 1954, the Chicago School from 1955-1963, the University of Virginia, and the University of Oregon from 1963-1971.]

the U.S. Golden Age in Capitalism was driven by “increased money velocity which financed about two-thirds of a growing GNP, while the increase in the actual quantity of money has finance only one-third.” In other words, the ratio of the money supply to GNP had fallen.

The economic solution is to drive the banks out of the savings business, aka, the 1966 Interest Rate Adjustment Act

The "wealth effect" was the worst possible outcome. Bernanke bankrupt 1/2 of the home builders. Then new residential construction fell off a cliff:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HOUST1F

So, continuing QE boosted housing prices to unaffordable levels. And B got the Nobel?

This is awesome, as always.

Why is the GDP deflator the most timely indicator of inflation available? Aren't there other more timely indices?

On your lack of signs of a near term recession, what makes you so confident? Are you looking at credit spreads primarily? Couldn't there just be a lot of lag effect of hiking that we are not seeing yet but that could come quickly at a certain point?

Thank you for doing what you do. It is much appreciated.

Scott,

The rise in the 10 year yield in the last two months is huge, 130-140 bps. Is this an extreme reaction to “higher for longer “ and if so is there data that shows this is the case? I am thinking of the past when you showed the extremes the stock market had reached by relating the VIX to the 10 year Treasury yield.

Thank you for your great insight and analysis over the last 15 years!!!

Teton, re GDP deflator: It’s a good measure of inflation because it takes into account the entire economy, not just consumer goods. It’s timely because it covers the most recent 3-month period.

Is there any weight to this argument: CBs intentionally cause the bond sell-off in order to rebuy their debt for less. Hence the higher yields.

some supply side economists believe that inflation does indeed cause higher( long term ) interest rates , and the FED is just following

Scott,

One of the cornerstones of your " no recession" story is the banks ability to lend (high level of reserves). As the yields go higher the banks have losses on their bonds portfolio (close to 800 bln USD). What is the impact of that on their lending ability?

The floating risk-free interest rate on reserve balances is @5.40%. So, there's not much incentive to lend.

Adam: one of the cornerstones of my "no recession" story is not bank lending, although a contraction in bank lending could certainly complicate things (so far there has not been a significant contraction). Why impresses me is the degree of liquidity in the bank system and financial markets in general. Money is not in short supply; it is abundant. Prior Fed tightenings caused recessions because the Fed created a shortage of liquidity in order to boost short-term lending rates. Now the Fed simply raises the rate it pays on reserves. Financial conditions are quite "normal" these days, to judge by credit spreads and swap spreads.

Short-term rates of 5.4% certainly reduce the incentive of banks to lend, and apparently 5.4% short-term rates also discourage spending and encourage holding onto money balances. Enough to have brought inflation down significantly.

Thanks for the explanation. Always appreciate your comments.

Haven't we seen this before? The Fed is aware inflation is approaching desired levels but is attempting to overshoot and induce a "soft landing". With a modest rise in unemployment, a softer labor market would temper future employee/unions pay increase demands, thus limiting wage increases that would reignite inflation.

Unfortunately, the Fed has always had trouble with inducing "soft" and instead produces "hard".

Many thanks Scott for your excellent data/charts, analysis and commentary. Much appreciated.

Reply to your response “Monetizing deficit/Argentina”:

Is there not now a legal pirouette which allows the FED to indirectly buy American bonds via US banks under the guise of facilitating trade and the solidity of the banking system?

The FED cannot buy bonds on the primary US debt market. On the other hand, I understood that it provided credit facilities to the banks (via the provision of “illiquid” collateral assets) which allowed the US banks to buy American debt on the primary market under the pretext of solidifying their balance sheets and liquidity of the system. Ultimately, this scheme amounts to more or less the same thing as a direct purchase from the FED on the primary market (Argentina) except that the risk is covered by the banking system which will be protected by the FED in the event of default.

Best regards,

Joric

"legal pirouette which allows the FED to indirectly buy American bonds via US banks under the guise of facilitating trade"

This is where the Fed has been allowed to take actions that are clearly meant to be illegal, but have indeed created ability for other legal entities buy and sell securities instead of the Fed. To me it's like somebody hiring somebody else to commit a crime. For the rest of us, if we do the hiring, we are also guilty. For the Fed, this appears not to be true.

In ~2008 they created some entities to own various securities (don't recall the details), and I think in the past several years they created "special vehicles" (don't recall the actual name) to buy and sell securities of private companies- clearly not legal for the Fed to do directly.

I don't understand how this is legal.

this from Macintosh at WSJ today: "Isabel Schnabel, a member of the ECB’s executive board, said recently that it was possible both for the soaring money supply in 2020 to be a useful indicator of the inflation that came, and for the shrinking money supply now to provide little reason for concern.

She argues that some of the measured money destruction might be no more than a rebalancing of savings into higher-interest, long-dated accounts and assets such as government bonds, which aren’t captured in the traditional measures of supply. Money as measured by M2 or M3 goes down, but not because households or businesses are being more cautious."

care to comment Scott?

paywalled...https://www.wsj.com/finance/monetarism-is-back-it-may-not-last-decae7bf?mod=hp_lead_pos3

re: "which aren’t captured in the traditional measures of supply."

Virtually all demand drafts cleared through total checkable deposits. That's why the G.6 Debit and Deposit Turnover Release was so important.

Christian, re money supply. The WSJ article you link to is a classic, in that it only refers to money supply and not money demand. This is an almost-universal mistake made by nearly all analysts and even the Fed. This is what I’ve been emphasizing for many years: you can’t look at money supply only, you have to look at it relative to the demand to hold the money that is being supplied.

Re: Lending. We are seeing very little lending for commercial real estate projects and M&A deals. I have had two deals for $100MM+ commercial real estate projects (multi-family and retail) fail to close because lenders backed out. Our corporate M&A partners are seeing deals canceled because companies can't get financing. I don't know if this will all lead to a recession next year but many of our clients are concerned.

Fred: thanks for you comments. There's no doubt that high interest rates have had a huge impact on the real estate market, both residential as well as commercial. As of August, total construction spending was still rising, up over 7% year over year. But inside this we have seen weakness in residential (-3% yoy).

If the Fed doesn't ease up, it would not be surprising to see construction spending weaken significantly over the next 12 months, and this could be the spark that triggers a recession sometime next year. I hope it doesn't come to that.

The Israeli/Hamas war that started over the weekend appears to have jolted confidence by enough to put the Fed on hold for the foreseeable future, and that could have a profoundly positive impact on nearly everything. As I pointed out in this post, what has really got the market worried is the possibility of more Fed tightening and a prolonged period of high interest rates. If the Fed is beginning to get the message that this not only won't be necessary but might even pose unnecessary risks, then we could see a significant decline in 10-yr Treasury yields, and that in turn would result in a significant decline in mortgage lending rates. Lower mortgage rates would boost demand for real estate, and that could absorb what otherwise might be a glut of new construction coming on the market.

As long as increases in M2 go into asset prices, retail inflation - and interest rates - can remain very low (as they have for decades).

But the moment that increases in M2 start going into the real economy, interest rates do matter. I think this is what we are just beginning to see.

We have become used to the asset inflation scenario as if it is normal (more than doubling of P/E ratios). But that 6% "long-term trend growth" in the money supply, facilititated by the Fed, without a commensurate 6% growth in the economy/GDP, or without retail inflation, cannot continue indefinately. It is, as well, a type of theft from the middle and lower classes (by making assets unaffordable for them).

I have a question for Salmo, or anyone else that knows.

I assume that banking originally was taking in actual banknotes/gold from depositors and then loaning that physical money out.

When did the reverse begin, when loans were made first and deposits were the result, i.e. electronic money? And what laws allowed this change? Thank you.

When goldsmiths realized they could "loan" gold by issuing more receipts to borrowers than the actual amount held as "reserves", borrowers who agreed to pay back the "loan" + interest.

Interesting. Thank you Thenagain. Makes sense. I suppose once one goldsmith started doing it, all the rest had to follow. I guess "receipts" (banknotes, etc.) had been accepted for a long time. At some point this transmorgified into issuing them without the gold behind it. Thanks.

Yes Richard, what is referred to is the creation and eventual recognition and widespread use of fractional reserve banking. Like most things in life not enough money in the system creates friction and inefficiencies (John Law, a long time ago, had well explained that part) but too much of a good thing (money supply versus underlying economic activity) also leads (eventually) to unintended consequences. Like you mention, asset inflation (like weight gain) is related to pleasurable sensations but inflation tends to eventually rear its ugly head in these instances and "dealing" with inflation usually means (eventually) popping some bubbles. At least that's what history and rationality say but maybe this time is different?

Thank you Thenagain. I will read about John Law (I started reading a little about him; very colorful start to his life).

Post a Comment