Chart #1

Chart #1 compares the level of the S&P 500 to the level of the Vix "fear" index. The two tend to move in opposite directions: rising fear levels result in lower stock prices, and vice versa. The Vix index is back down to pre-Covid levels, and stocks have been rising—though not yet to new highs.

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows Bloomberg's Financial Conditions Index, a reliable measure of the underlying health of the financial markets and thus a forward-looking indicator of the health of the economy. Conditions are about average these days, so it's reasonable to expect the economy will continue to grow, albeit slowly (~2%).

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares industrial production levels in the U.S. and the Eurozone. There has been very little progress in the level of industrial production since 2007, although the U.S. economy has been somewhat more dynamic than the Eurozone economy by this measure. Still, nobody's posting gangbuster numbers.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows U.S. manufacturing production, a subset of overall industrial production. Here again we see very little improvement in recent decades. Ho-hum. But neither do we see any deterioration.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows two measures of producer price inflation at the final demand level. This captures inflation at an earlier stage of inflation pipeline than the CPI. By either measure, inflation has fallen to less than 2%. The Fed's done. The CPI won't be far behind, except for the fact that energy prices have spiked of late—through no fault of the Fed's. Biden's Green agenda is at work here, as well as fallout from the Ukraine-Russia war.

Chart #6

Chart #6 shows two broader measures of inflation at the wholesale level (as of August). Here again we see inflation back down to where it should be: 2% or less.

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows the 6-month annualized rate of change of the CPI compared to the CPI less shelter costs. As I and many others have been pointing out for the past several months, shelter costs have been artificially inflated as a result of the BLS using backward-looking statistics related to housing prices.

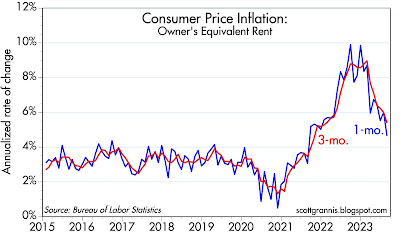

Chart #8

Chart #9

The major component of shelter costs used in the CPI comes from what is called Owner's Equivalent Rent. As Chart #9 shows, OER is driven primarily by housing prices 18 months in the past. The chart shifts OER to the left by 18 months to correct for this. Here we see the peak in housing price inflation corresponding to the peak in OER. Since housing prices peaked over a year ago, OER is now beginning to decelerate. That deceleration is showing up very clearly in Chart #8, which looks at changes in the level of OER over 1- and 3-month annualized rates. What this means is the OER is going be contributing meaningfully to lower rates of CPI inflation in coming months.

The FOMC meets next week, and I see no reason for them to raise rates yet again. The big question is when they will begin to lower rates. Today the market is betting on a 30% chance of another rate hike at the November meeting, with rate cuts not likely until mid-2024.

It's important to note (again) that Fed tightening this time around is fundamentally different from tightening cycles in the past. The main difference this time is that the Fed is not draining reserves from the banking system. Reserves are still plentiful at over $3 trillion. That's a huge deal. Chart #2 makes the point another way: there is no shortage of liquidity in the financial markets, unlike during periods leading up to recessions in the past. The only thing that is "disturbing" the economy this time around is that short-term interest rates are relatively high. That doesn't necessarily pose a threat to the economy. It simply makes it more attractive for people to hold money—that is, higher rates increase the public's demand for money, and that in turn neutralizes the amount of "excess" M2 that is still circulating. See this post from late August for a more detailed explanation.

8 comments:

re: "Reserves are still plentiful at over $3 trillion"

https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/economic-synopses/2023/08/23/the-mechanics-of-fed-balance-sheet-normalization.pdf

There's still a "savings glut". The volume of outside money is still suppressing interest rates.

Powell says: “As is often the case, we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies,”

The "the longer-run, or natural, rate of interest that is neither restrictive nor stimulative – the “r-star” rate of interest" is fictitious.

Higher real rates of interest are not restrictive, they are necessary for saver-holders, for balancing money demand.

The O/N RRP facility is a spectacular example of monetary policy failure:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RRPONTSYD/

Now down to $1,401.403T.

The stimulus that is represented by Atlanta GDPNow @ 4.9% comes from O/N RRPs and the transfer of funds through MMMFs. MMMFs are not supposed to be counted in the money stock. That's a double counting. So, the drawdown of the O/N RRP adds liquidity to the markets.

That, and the transfer of funds through the MMMFs, from bank-held savings, activates money (puts savings back to work).

The Austrian School gets this right. The FED doesn't know a credit from a debit. I.e., the MMMFs are nonbanks, and customers of the DFIs.

Link: Primer: A Deposit’s Life

https://fedguy.com/primer-a-deposits-life/

How do you think the TGA was funded?

Scott, Salmo Trutta is always talking about O/N RRPs. No offense Salmo, I appreciate the extra information, but I have trouble understanding everything you say in the comments (partially due to the limiting comment format and partially due to my own lack of basic comprehension of the topic).

Can you, Scott, shed some light on the O/N RRP topic and whether you share the same understanding of it/concern that Salmo clearly does?

Thanks to you both.

I'm not "concerned". I just think the FED's accounting is wrong. It’s virtually impossible for the Central Bank or the DFIs to engage in any type of activity involving non-bank customers without an alteration in the money stock.

And I think the economy is being run in reverse. Lending by the banks is inflationary, whereas lending by the nonbanks is noninflationary (other things equal).

Rather than bottling up existing savings, the authorities should pursue every possible means for promoting the orderly and continuous flow of monetary savings into real investment (which increases the real rate of interest). I.e., the FED should drive the banks out of the savings business (which contrary to the FED, doesn’t reduce the size of the payment’s system).

Powell should continue with QT, while lowering the administered rates.

Re: O/N RRPs (overnight reverse repurchase agreements): The Fed pays interest on reserves with the objective of setting a floor on short-term interest rates. However, that limits the number of banks that can lend money to the Fed. Left out are medium and smaller banks, plus a host of non-bank lenders. If these institutions have surplus funds that can't be placed at a rate that is competitive to what the Fed is paying, that would put downward pressure on short-term interest rates, thus foiling the Fed's objective. The O/N RRP facility solves that problem by allowing these other players to lend to the Fed at a rate similar to what the Fed pays on reserves. Currently the Fed is paying interest on about $3.3 trillion of reserves, and effectively paying a similar rate on about $1.45 trillion through its repo facility. That latter figure peaked at about $2.5 trillion at the end of last year, and has since been falling.

Should we expect shelter to begin to reflect disinflation in the next report?

Any comments on the energy situation as it pertains to CPI?

Thanks, as always.

Re shelter costs: Shelter costs are growing at a slower and slower rate, so they will be adding less and less to overall inflation. It will probably take 3-6 more months of this before shelter costs stop increasing. At that point shelter costs may even begin to decline somewhat.

Post a Comment