I'm a monetarist when it comes to inflation. As Milton Friedman taught us, inflation is what happens when the supply of money exceeds the demand for it. The best measure of the supply of money is M2, but nowhere is there a statistic which directly measures the demand for money. Money demand can only be measured after the fact, by observing changes in the money supply and changes in inflation. For example, if inflation rises we can be sure that the demand for money has been less than the supply of money. Even if M2 growth is low, inflation can rise if the demand for money is falling. And as we saw in late 2020, rapid M2 growth can occur even as inflation remains low, because back then the demand for money was very strong given all the uncertainties and shutdowns. (Check out this post from October 2020 for more background on this.)

The Covid era has given us something akin to a laboratory experiment in the interaction between money supply and money demand. We've seen a massive, unprecedented increase in the money supply followed by an equally impressive decline in the money supply. Meanwhile, inflation has gone from low to high and is now halfway back to normal. The lags between money and inflation have been "long and variable," as Friedman noted. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve has paid virtually no attention to any of this, and neither has the press nor the vast majority of economists. There are lessons to be learned here, and fortunately, there is reason to remain optimistic about the future.

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of M2 (blue line) and its 6% per annum trend growth rate (green line) which has been in place since 1995. According to data released yesterday, M2 increased by $131 billion in May, breaking a 9-month losing streak totaling just over $1 trillion. M2 has fallen 4% in the past 12 months, and is up only 0.9% in the past 24 months. Yet M2 is still about $2.6 trillion above where it might have been in the absence of the Covid crisis. I've argued that this "extra" amount of M2 serves as a cushion against recession, because it means that the economy is still flush with cash and liquidity. See this post for more on why liquidity is so important to both the economy and financial markets.

Chart #2

Chart #2 compares the growth rate of M2 to the 12-month running total of the federal deficit. This strongly suggests that the $6 trillion of federal deficit spending in 2020-2022 was financed by money creation. The one good thing here is that the increased deficit over the past year has not resulted in any increase in M2, because the spending has been financed by borrowing, not money creation. This is as it should be. Bottom line: the source of the inflation surge in recent years has dried up, and inflation is on the way out.

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares the growth of M2 with the rate of CPI inflation lagged by one year. The chart suggests that there is approximately a one-year lag between changes in money supply growth and changes in inflation. Given the dramatic decline in M2 growth which began early last year, the chart suggests we will see a similar decline in inflation over the next 6 months or so. As I've argued for months, the decline in inflation is well underway.

Chart #4

Chart #4 is my attempt to quantify "money demand." I'm one of the few economists who pay attention to money demand because it's crucially important: after all, inflation is what happens when the supply of money exceeds the demand for money. Check out this post from October 2020, in which I elaborate on how strong demand for money can offset rapid growth in money supply. Money supply can be abundant, as it was in 2020, but inflation didn't show up until April of 2021. I think that's because the demand for money was very strong in 2020: everyone was hoarding money because of all the Covid-related uncertainty. Inflation began to appear in 2021 only after confidence picked up and life began returning to normal after the first round of vaccines—people no longer wanted to accumulate money. People began spending the money they had accumulated, and that aggravated the problem of supply-chain disruptions, driving prices higher. This post from March 2021 elaborates on these thoughts.

Think of the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP as the amount of cash and cash equivalents that the average person is willing to hold, expressed as a percent of their annual income. As the chart shows, money demand fell rather dramatically beginning in late 2021, and inflation peaked about six months later. In recent months the decline in money demand has slowed quite a bit; I think that's due to 1) the Silicon Valley Bank failure and 2) rising real interest rates. People are more cautious about holding money these days, and it's not a coincidence that most of the M2 increase in May was due to a $76 billion increase in retail money market funds which are now yielding almost 5%. Holding money when rates are 5% is a lot more attractive than when they were almost zero back in early 2022. Higher interest rates also discourage borrowing, especially for mortgages; mortgage originations have fallen by 50% in the past year. (Note: being less willing to borrow money is equivalent to being more willing to hold money.)

For the past 18 months the Fed has been raising short-term interest rates in an attempt to bolster the demand for money. If they hadn't done that, plunging money demand would have pushed prices even higher. In effect, they were trying to prevent the public from rapidly spending all the excess money that accumulated in the 2020-2021 period. And it has worked. The May pickup in M2 suggests there has indeed been a slowing in the decline in money demand.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows nominal and real yields on 5-yr Treasuries (red and blue lines), and the difference between the two (green line), which is effectively the market's expectation for what the CPI will average over the next 5 years. Inflation expectations today are about 2.1%, which is very close to what inflation averaged in the 20 years leading up to the 2020 Covid crisis. In effect, the bond market believes the inflation problem has been solved. The yield curve is very inverted these days (i.e., short-term rates are much higher than long-term rates), which means that the bond market expects the Fed to lower short-term interest rates dramatically over the next year or two—because the market believes the Fed will eventually realize that the inflation problem has been solved.

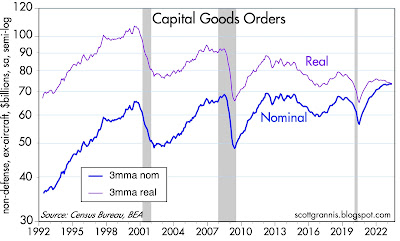

Chart #6

Changing the subject: Chart #6 shows the 3-mo. moving average of capital goods orders in both nominal and real terms. Capital goods orders ("capex") are investments that companies make which will boost future productivity (i.e., purchases of machinery, computers, tools, new plants). As such, capex is a leading indicator of future economic growth. Nominal capex has reached a new high in nominal terms, but in real terms capex has been lackluster to say the least: it's fallen almost 30% in the past two decades. I believe this tells us that economic growth in coming years will also be lackluster: 2% or less per year.

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows Bloomberg's index of financial conditions, with the components listed at the bottom. According to this, the outlook for financial markets and thus the economy is "normal."

Summary: There is nothing to fear from the behavior of M2; money and liquidity are still abundant and key indicators such as swap and credit spreads tell us that the economy's fundamentals are still sound. The source of our inflation problem has dried up and inflation is on its way back to normal. The Fed was slow to react to all this, but they have not yet made a significant mistake. It's therefore not surprising that the stock market has been creeping higher.

18 comments:

The "demand for money" is simple. Banks don't lend deposits. Deposits are the result of lending/investing. Hence, all bank-held savings are un-used and un-spent, lost to both consumption and investment, indeed to any type of payment or expenditure. It's stock vs. flow.

That's what Dr. Philip George's "The Riddle of Money Finally Solved" is all about.

See: “Should Commercial Banks Accept Savings Deposits?” Conference on Savings and Residential Financing 1961 Proceedings, United States Savings and loan league, Chicago, 1961, 42, 43

Alfred Marshall’s cash-balances approach (viz., a schedule of the amounts of money that will be offered at given levels of “P”), is where at times “K” is the reciprocal of Vt, or “K” has the dimension of a “storage period” and “bridges the gaps of transition periods” in Yale Professor Irving Fisher’s model.

Deposits are indeed a stock. And as with any stock of assets, what's important is the public's willingness to hold/own that stock. When that willingness changes, that's when things happen on the margin. Hence the importance of changes in the demand for money.

That capital goods orders chart is depressing, to put it mildly.

Let's hope the data-collection is missing something. Maybe capital goods are cheaper than before but better?

Offshoring of industry?

Sure seems like inflation is losing with each inning. China and Vietnam are below central bank inflation targets.

A couple of years of above-target inflation in the US is not the end of the world. The Fed can take its time.

Capital Goods Spending- is ~50% below its 1999 peak per capita, ex-aircraft/transportation and ex-military. Lack of construction, is my guess- not enough residential construction or processing plant construction. Some of the foundations and structural hardware in processing plants, such as refineries, is 100 (yes, 100) years old. They just keep adding bits and pieces, upgrading efficiency/control. They avoid spending capital on new plants/refineries.

GDP vs Wages- this is a very interesting comparison. GDP has been trending down for decades, but inflation adjusted weekly earnings/wages have been rising since~1995, though not in a straight line. Real weekly wages have been edging up for about a year now. These numbers started to turn positive when the GDP did last year. GDP is a bit stronger than expected so far in 2023. Very interesting for a time when the Fed is trying to slow the economy. I am still concerned the Fed Chair has some reputation/legacy on the line and will not hesitate to hurt the economy "more than necessary" to get inflation down.

Changing the subject: Chart #6 shows the 3-mo. moving average of capital goods orders in both nominal and real terms. Capital goods orders ("capex") are investments that companies make which will boost future productivity (i.e., purchases of machinery, computers, tools, new plants). As such, capex is a leading indicator of future economic growth. Nominal capex has reached a new high in nominal terms, but in real terms capex has been lackluster to say the least: it's fallen almost 30% in the past two decades. I believe this tells us that economic growth in coming years will also be lackluster: 2% or less per year.

What are the fastest growing sectors of the US economy? How much capital goods investment does it cost to build an app? Increase your "services" business both in the US and around the face of the earth? Produce software and services for beloved Apple, ChatGPT, etc...Questions to ask when you are comparing economic growth of the present versus the past?

Money demand comes and goes, but supply is forever.

Scott, although your analysis seems correct in the short term, it does not in the long. How do think the additional debt will eventually be paid for? Taxes or inflation. One or the other. The debt is what is important.

Richard H: Money supply (M2) is not forever. It can shrink if people repay debt, just as it can expand if banks make new loans. I agree it is not always easy to understand what is happening to money demand, but I think it provides a useful framework for thinking about how the Fed can use interest rates to control inflation. Remember, monetary policy in a time of abundant reserves is very different than it was before 2008, when the Fed restricted the supply of reserves in order to force rates higher.

I would argue that debt is not as important as government spending. Debt can be paid for by a) growing the economy, b) reducing spending, c) increasing tax revenues, and/or d) allowing inflation to rise. Spending is the problem because it permanently wastes precious resources, and that in turn weakens the economy.

BTFP is at 103B this week, a new record.

Where would the markets be without it?

Roy: The banks have been backstopped since the Banking Act of 1933 (if the FOMC has the will to exercise this right). However, Bernanke was late to the game in 2008.

ST,

Are the markets doing well because they estimate the economy will do well in the future or is it because of the Fed's stealth liquidity?

Scott, I follow you and I agree with your and Friedman's economic school. But..... inflation is "entrenched". The Fed several months ago said it feared that, and wanted to take steps to prevent that. But they werent agressive enuff early enuff. In my opinion, as a general coservative and lower middle class incomer, the Fed has allowed the tail (market, press, talking heads, financial blogs, politicians) wag the dog (the Fed itself)! I believe there is benefit in surprise rate hikes or surprise rate cuts, taken in the middle of the nite like they once were. The present system of well telegraphed actions in the hope of not surprising the markets is too much like the Fed"showing their cards" in a high stakes card game. With the use of modern sophistication, communications, and information available in today's financial world has come the gaming of the system.

Re: Stevieray

It's ultimately really only about setting an interest rate so that money supply matches money demand. All of the other things you're talking about are a sideshow, a surface level game. Not that they don't influence the market, everything can. But they don't matter at all in terms of effective policy.

Supply has slowed/dropped due to a lack of Covid payments from Washington.

Demand has risen due to higher interest rates from the Fed.

Inflation is falling for these two reasons.

End of story.

Interest is the price of credit. The price of money is the reciprocal of the price level.

Lending/investing by the DFIs (deposit taking, money creating institutions), expands both the volume and the velocity of new money. I.e., lending/investing by the DFIs is inflationary.

Lending/investing by the NBFIs (nonbanks) increases the turnover of existing deposits (a transfer of ownership), within the commercial banking system. I.e., lending/investing by the NBFIs is non-inflationary (other things equal).

The correct solution to stagflation is the 1966 Interest Rate Adjustment Act, i.e., drive the banks gradually out of the savings business, lowering deposit rates, while draining bank reserves.

Scott,

Thanks to you, I understand that inflation is what happens when the money supply outpaces money demand. Possibly oversimplified, but it's a nice one-word description of the likely outcome.

In similar terms, what is the clearest way of describing what happens when the demand for money gets too far ahead of supply?

Re: "what is the clearest way of describing what happens when the demand for money gets too far ahead of supply?"

When the demand for money exceeds the supply of money, money becomes scarce and its price therefore rises (as would the price of anything in short supply). This is otherwise known as deflation: when a dollar today buys more than a dollar bought yesterday. Or, if you prefer, when the dollar price of things falls; when the price level falls.

Deflation is the opposite of inflation.

Hello, I recently landed on your blog and I really appreciate you publishing them. I see that you also publish them on substack and substack recently add text-to-speech option that you can enable on your articles at https://airtable.com/shr11c70LRWq9saOb

It would be nice to have this option for people like us who is more auditory

Economic indicators:

- Jobs- better than people have expected, however, the quality of the jobs is starting to suffer: government and service jobs dominate

-Inflation- various measures show flat to slowly declining. The PPI has kind of plateaued for a year now, so it's not helping reduce rates.

-Growth- for about the past 2 years, GDP growth is around 1.6%

-Productivity- (the acid test for an economy) is negative/declining for the past 2.5 years

So, no recession, but not good. It reminds me of ~1974-1982, between several recessions.

It's textbook stagflation.

Post a Comment