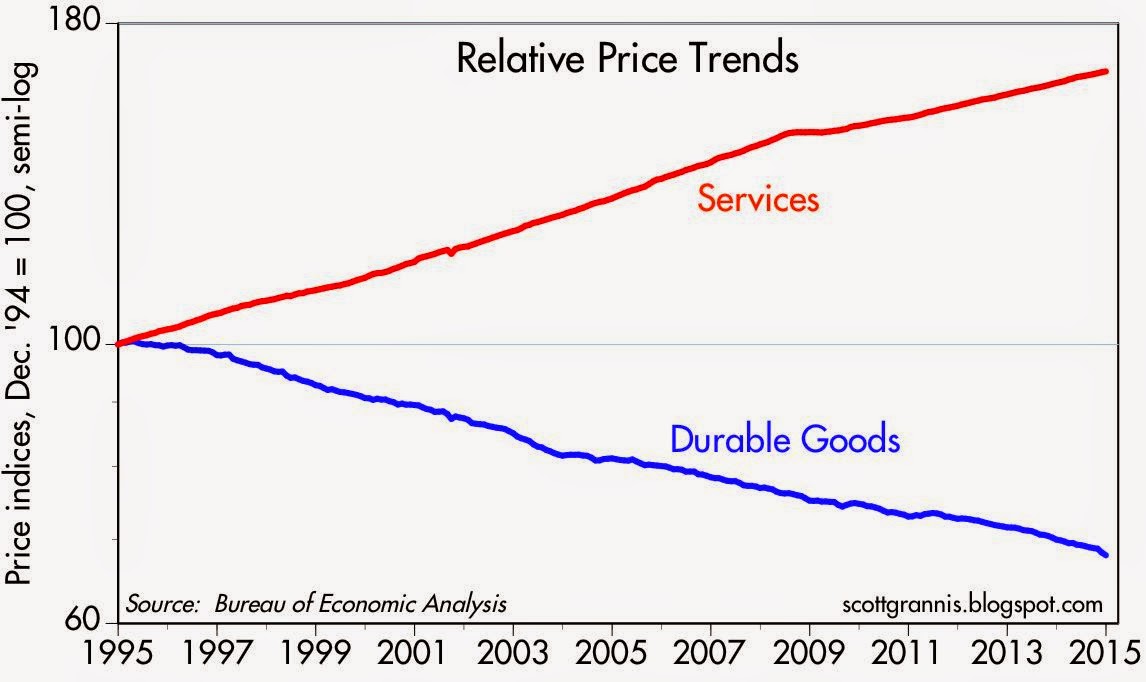

You can best appreciate what's going on with prices by disaggregating the personal consumption deflator into two of its three components: services (a good proxy for labor costs) and durable goods:

Even though the prices of many essential goods have fallen enormously and our living standards have increased, in a technical sense—assuming it's actually possible to estimate just how much more value for our money we're getting when we buy durable goods these days—prices on average have been rising. The first chart above shows inflation according to the overall personal consumption deflator (whose components include services, nondurable, and durable goods) and the core personal consumption deflator (which excludes food and energy). The second chart breaks out the rate of inflation in services and durable goods. The past 20 years have seen service sector prices rise by 2.5% and durable goods fall by an annualized 2% per year. Nondurable goods (e.g., commodities) prices have risen by an annualized 2.0% over the same period. Overall, prices have risen an annualized 1.8% over the past 20 years.

To understand durable goods deflation, consider the iPhone, which was first released about 7 ½ years ago. Although the price of an iPhone hasn't changed much over the years, its capabilities have multiplied. Before the iPhone, portable phones were largely just that: portable phones. The first iPhone showed us that phones could also be computers and simple cameras. Today, the iPhone produces full-length, high-definition movies and breathtaking photos; it's a 64-bit supercomputer that fits in your pocket; it monitors your health; it pays your bills with the touch of your thumb; it gives you directions to any place in the world, and the best route to avoid traffic; it holds your entire music and photo collection; it is a trading platform for stocks and bonds; it's a real-time news ticker; it accesses the world's knowledge base in seconds; it takes dictation; it's a video arcade and a movie theater; it communicates with anyone in the world in seconds; it can hold a library of books; and it can diagnose illnesses, to name just a few of its hundreds of thousands of applications for this miraculous gadget. For a mere $650, the iPhone saves you tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. Meanwhile, smartphones have spawned new industries (app developers), disrupted others (taxis), and are revolutionizing many others.

One more example: As the chart above shows, the cost of personal computers and peripherals has fallen by more than 95% since the BLS first started tracking them in 1998. That's taking into account, of course, all the extra value (faster speeds, more capabilities, more memory) that, say, $1000 buys today vs. 15 years ago. And by the way, despite two decades of falling prices, the computer industry has thrived. Deflation is not necessarily a death knell for anyone.

It may be hard to understand, but it's good news for just about everyone.

7 comments:

Excellent post. Yes, measuring inflation is an art not a science.

Another tricky area is the cost of housing especially when there is an urbanizing population moving into more-expensive housing, and housing becoming an investment vehicle. So what is inflation, and what is appreciation?

The Fed is a bit koo-koo to peevishly fixate on microscopic rates of inflation---official rates that may overstate Iinflation anyway.

Better to target sensible real growth.

"..making it difficult if not impossible to measure "inflation" or living standards by any objective measure."

Real GDP growth (per capita) is the measure of living standards. I for instance use Amazon and other sites quite a bit. This not omly gets me near the lowest price but also doesn't cost me time and personal transportation costs. Both of these benefits add a lot to my quality of life giving me more time and money. Curent GDP calculations do not take this into account. Further, I believe this added efficiency is part of the cause of our under employment as people aren't needed as much.

Scott, what do you think of the median CPI? It is reported for December to be 2.1% annualized which is higher than other methods.

I get your example with computers -- how about cars! The issue with IT products is that the Moore law is very important. Plus one aspect that is forgotten is that lots of value is given to things that dont really matter.

Sure, an Iphone can take picture -- but I had a perfectly good film camera that could do the same! Sure my computer is faster, but is that really an improvement to my daily life?

Finally, it is wrong to compare the price/cost of new technology with "older products". The comparison could also be made with the introduction of steel radial tires. Our parents had more flats, had to replace tires far more often. Changes in technology are bad at discussing inflation.

However, good are far less often produced on our shores. Rather they are produced in China/Vietnam and India -- by workers that earn a pittance -- agains goods here were produced, but the "service" element of these goods were sent to lower cost producers.

But your point is valide as far as it goes

The BLS tries to account for quality increases with hedonic modeling.

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiqa.htm

Re median CPI. I think this is something that's worthwhile following, along with other measures of inflation like the PCE core deflator and the GDP deflator. When I look at them these days, I see inflation that is probably running about 1.5%.

Falling prices emanate from two sources: a fall in demand or an increase in supply. The 1930s deflation was a demand side deflation as the economy shrunk. The current deflation is supply induced as Scott points out and is a good thing. For politicians it is important to distinguish the source of that deflation

Post a Comment