When yields on risk-free assets are close to zero, it only makes sense to hold those assets if you need liquidity and/or are highly concerned about the potential for losses in other assets, most of which are yielding substantially more. From a macro perspective, the fact that significant assets are being held with virtually a zero yield can be interpreted as a sign that the market is very worried about a recession, since that is the one event most likely to create widespread losses in risky assets.

This has been the case for most of the past 4 years (during which time the yield on 3-mo. T-bills has averaged about 0.1%), yet the economy has avoided a recession and the returns on almost all alternative assets have been astounding. The returns on cash have actually been negative in real terms, since inflation has averaged 2.2% a year over the past four years. Cash, the risk-free asset, has produced an annual loss of purchasing power of over 2% for four years running. The S&P 500 index, on the other hand, has produced annualized total returns of 16.8% for four years running.

With almost $7 trillion sitting in bank savings deposits earning practically nothing, and with tens of trillions invested in risk-free assets around the world, there are therefore many millions of people and investors who need a recession to justify their current asset allocation.

Are there any signs of a budding recession? None that I can see in the recent data.

Weekly unemployment claims are volatile around this time of the year since the seasonal adjustment factors can be large. The 4-week average of claims, which eliminates a good deal of this volatility, is now at a post-recession low. No sign here of any recession or even an economic slowdown, to judge by this relatively fresh and sensitive indicator of conditions in the jobs market.

No sign here either of a recession, to judge by the Challenger tally of announced corporate layoffs. There is no sign of any unusual downsizing.

Meanwhile, it's almost certain that a housing market recovery is well underway. As the above chart shows, the stocks of major home builders are up over 100% in the past 16 months, and they are up 270% since their recession low. Housing starts are up 77% since the beginning of 2011.

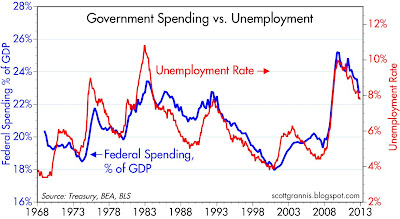

The zero growth reported for the fourth quarter of last year was the result of a downsizing of defense spending and a slowdown in inventory accumulation. Reduced government spending is not necessarily a bad thing, since it frees up resources for the private sector. Inventory investment is quite likely to bounce back, having been depressed in recent months by the uncertainty of the "fiscal cliff" which has since been resolved.

All of this is being repeated on a global scale. The value of global equities has more than doubled since their early-2009 low. $25 trillion has been earned by the holders of those equities, compared to a loss on the purchasing power of the tens of trillions that was held in cash over the same period.

Investors are notorious for following the money rather than anticipating where the money will be made, and $25 trillion in gains ought to be enough to get a lot of people's attention. We may finally be at the point where the private sector stops trying to deleverage and begins to releverage; when investors stop taking money out of equity funds in order to add to bond funds; and when investors try to reduce their cash balances in favor of riskier assets. The Fed and all other major central banks have been trying very hard to make this happen, and it would be foolish to think they won't be successful. By keeping interest rates on risk-free assets extremely low, the Fed is trying to destroy the demand for those assets, and trying to encourage money to find its way into other more riskier asset classes. The money can't actually leave cash, but the attempt by the private sector to reduce its cash exposure (and/or increase its borrowings) in favor of equities or real estate could unleash a powerful change in relative asset prices. Ultimately, the yield on cash will rise significantly, while the yield on other assets will decline as their prices rise.

All it takes for this to happen is to simply avoid a recession.