I'm a fan of nearly everything Trump has done this year, with the exception of his Terrible Tariffs. As I and many others have explained, Trump's threat to raise tariffs is a terrible idea because they're meant to fix something that isn't broken (Trump's claims to the contrary notwithstanding).

Our trade deficit with China, for example, means that we buy more goods and services from China than they buy from us. The difference, termed the trade "deficit," is evidence, in Trump's mind, that China is "ripping us off." But by the laws of commerce, he who sells more goods and services than he buys must do something with the net amount of money he receives. In the case of China-U.S. trade, the dollars China earns from its commerce with the US must inevitably find their way back to us in the form of investment, security or bond purchases, or simply bank deposits. Simply put: you can't spend dollars in China.

China is not ripping us off because it already spends everything it earns from our trade deficit. In economic jargon, the deficit in goods and services we have with China is completely offset by a surplus in our capital account.

Where Trump has a legitimate beef with China and other countries is their use of tariffs to make US goods and services expensive and thus reduce their demand for our stuff. They would be better off—and so would all of us—if no one used tariffs. Free global trade is nirvana for everyone. Everyone wins when tariffs are zero.

Trump understood this back in 2018 when he said during a discussion with G7 leaders that all countries should eliminate tariffs and subsidies, because that would be "true free trade." Has he forgotten what he once believed in and fully understood?

You might think so after living through the global financial turmoil of the past week or so. It was a nightmare scenario. Trump was a madman determined to wreak havoc among global economies and global trade. I was so anguished I could only think that the prospects were so awful that Trump would be forced to back off. This couldn't go on. And suddenly, yesterday, it didn't. Trump gave everyone except China a 90 day reprieve and markets rejoiced. Today, however, second thoughts were creeping back in.

I agree with what Bill Ackman said yesterday. By waiting until panic set in before announcing a reprieve, Trump forced the world to see first-hand what the results of a global tariff war would lead to. And he also put tremendous pressure on China, the biggest bad actor of global trade, to change its ways. It was a master-stroke of persuasion. Until yesterday I had begun to fear that Trump was making a huge mistake. Now my fears have been assuaged. We're not out of the tariff woods yet, but the prospects for a favorable resolution have improved dramatically. Maybe those tariffs Trump threatened weren't so bad after all, if they help the world understand how bad they can be.

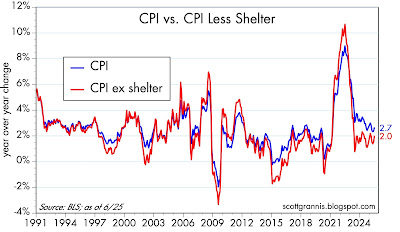

Now let me comment briefly on today's CPI release, which was a pleasant surprise. The chart below says it all:

Chart #1

Chart #1 compares the year over year change in the CPI index with the same change in the CPI index ex-shelter. The ex-shelter version of the CPI has increased by 2.3% or less for the past 23 months (since May 2023), and it has averaged a mere 1.7% per year for almost two years. In the past year, ex-shelter inflation was only 1.5%.

Only shelter costs have kept the broader CPI from long ago meeting the Fed's objective, and their impact is continuing to fade away.

To repeat what I said months ago,

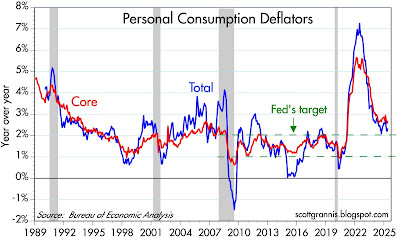

tariffs don't cause inflation. Only monetary policy causes inflation. So far the Fed has been doing a pretty good job of neutralizing the monetary excesses of 2020 and 2021.

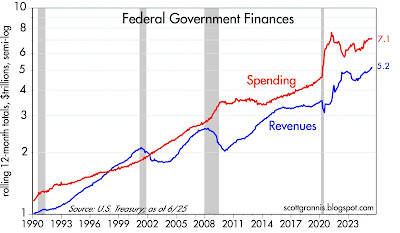

Chart #2

As Chart #2 shows, the M2 measure of the money supply is within shouting distance of the long-term trend growth that prevailed from 1995 through 2019. Excess money has all but disappeared, and Chart #1 goes a long way to proving it.

UPDATES (4/23/25):

The March data on M2 continue the trend described above. M2 is basically unchanged over the past three years, and is up at a modest rate of 4.1% over the past year. Excess money has been drained from the economy. Credit spreads have backed off from their recent highs and are far short of flashing even a modest yellow signal. Bank reserves remain abundant ($3.45 trillion) and the Fed is no longer threatening to make them scarce.

Trump got schooled by the market, so now he's dialing back his tariff threats. This is very good news. Tariffs are taxes, and nobody needs higher taxes right now. Paring back spending by streamlining our bloated bureaucracy is the best way to fix what's wrong with the economy. Let's do more of it.

Meanwhile, I won't feel comfortable until Stephen Marin, Trump's Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, and Peter Navarro, his tariff-loving trade advisor, are banned from the White House. Both advocate industrial policy on a global scale (e.g., devalue the dollar to promote US exports, and jack up tariffs on countries that don't buy enough of our goods) that has NEVER worked anywhere for anyone.

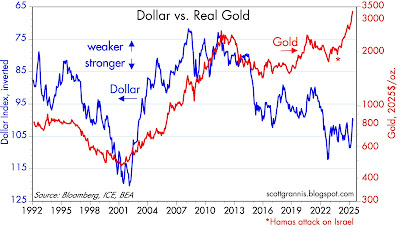

I would also like to see gold fall back to $2,500/oz. The current level of $3,300 is just way too high, reflecting extreme levels of discomfort and fear that are incompatible with a healthy economic environment.