Friday, July 29, 2011

Reading the bond and stock market tea leaves

Today's deeply disappointing GDP report has helped 10-yr Treasury yields to their lowest level of the year, and there's little doubt that the problems Congress is having over increasing the debt limit are contributing to the market's malaise. As my chart suggests, the current level of 10-yr yields is indicative of a market that expects a recession. The last time yields were this low or lower the market was last summer, when concerns about a double-dip recession were rampant.

10-yr yields are strongly influenced by the market's expectation of the future path of the Fed funds rate, and with the economy so weak and expectations for future growth so dismal, the market is now expecting the Fed to keep rates near zero throughout this year and most of next year; in fact, the market currently doesn't see much chance of any meaningful Fed tightening until the first half of 2013.

Are the bond and stock markets out of synch? Bonds are priced to a recession, but the S&P 500 is only 5% below its recent highs, and over 20% above last summer's lows.

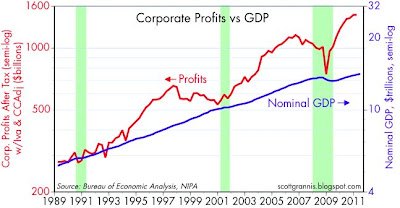

These two charts help explain what's going on. As a result of the recent revision to the past several years of GDP, corporate profits were revised to be much higher than before. First-quarter after-tax profits (which are based on corporate tax filings from the IRS) are now reported to be running at an annualized rate of almost $1.45 trillion, compared to the $1.26 trillion previous estimate. Relative to GDP, corporate profits are now at a new all-time high. Even though the recovery that began two years ago has been downright dismal, corporate profits have surged by almost 50% to record-setting highs.

Using NIPA profits as a proxy for all corporate earnings and the S&P 500 index as a proxy for the value of corporate equities, I've constructed the chart above. This shows that PE ratios have rarely been so low in the past 50 years. The market may be depressed by the economic outlook, but it's hard to ignore $1.5 trillion of corporate profits. If anything is sustaining the level of equity prices today, it's profits, not optimism. As a result, for those who believe that the debt limit will be raised and fiscal policy will improve—even marginally—current valuations represent real bargains.

GDP: less growth, more inflation

As this chart from Calculated Risk shows, today's historical revisions to GDP subtracted a lot—a little more than $200 billion—from real GDP. The recession now looks worse than before, and the recovery looks weaker. Real GDP has still not recovered to its 2007 high. Although growth in 2010 was revised upwards, growth this year has proved to be much weaker than previously thought. On a minor note, my original forecast in late 2009 that GDP would grow by 3-4% in 2010 has now been vindicated, since according to today's revisions, GDP expanded by 3.1% in 2010. But so far, first-half 2011 growth (0.8%) is much slower than the 3-4% I expected last December.

Much of what was subtracted from real GDP was added to inflation (i.e., nominal GDP didn't change very much, but its composition did). The first of the above two charts shows quarterly annualized changes in the GDP deflator before today's revision, and the second shows them after the revision, including the second quarter number. Previously, we had two quarters of deflation, with six quarters of inflation that was either very close to zero or negative. Now we see only one quarter of deflation, and only two that were close to zero or negative. For the first half of this year the GDP deflator has risen at a 2.6% annualized rate. The CPI rose at a 3.8% rate over the same period, so between the two we have clear signs of accelerating inflation.

This has to be a very surprising and even shocking result for establishment economists as well as for the Fed. As the above chart shows, real GDP is now over 12% below its long-term trend. This huge "output gap" should have been extremely deflationary, according to traditional Keynesian analysis, but that hasn't been the case at all. The Fed has been in a near-panic for the past three years, believing that the extreme weakness (aka "resource slack") of the economy posed the very real threat of a debilitating deflation, but deflation has proved to be only a fleeting phenomenon. If current trends continue, the Fed is soon going to be worrying about too much inflation, not too little.

Once again these developments underscore supply-siders' belief that growth can only come from hard work and risk-taking. Monetary policy can't create growth out of thin air, and neither can fiscal "stimulus" spending. The swimming pool analogy is very apt: fiscal spending "stimulus" is akin to taking water out of the deep end of a pool and pouring it into the shallow end—it achieves nothing and is simply a waste of effort. Real growth only occurs when people work more and/or someone figures out how to make the same amount of work produce more output.

If there is a silver lining to this gloomy GDP cloud, it is that fiscal and monetary policy "stimulus" have now been soundly discredited. Congress does not have the power to pull spending levers in order to speed up the economy, and the Fed can't speed up the economy by keeping interest rates at artificially low levels. In fact, fiscal and monetary policy errors of the sort we have lived with in recent years only serve to weaken the economy. Too much debt-financed spending only wastes the economy's scarce resources, while simultaneously boosting expected tax burdens. This in turn reduces the after-tax rewards to hard work and risk-taking, which explains why corporations have been so slow to invest their growing stockpiles of cash. Too much easy money only boosts speculative activity (which shows up as higher commodity and gold prices) while undermining the dollar and reducing investment.

Thursday, July 28, 2011

The end of the weekly claims seasonal problem

For most of this year, the weekly unemployment claims have been jerked around by seasonal adjustment factors that didn't quite match the typical seasonal variations that occur. As a result, claims were under-reported in late February and March, and over-reported in April. I've been blogging about this for a long time. Now I think this little sideshow is finally coming to an end.

The top chart shows the seasonally-adjusted data, while the bottom chart shows the actual data. Note that in actual data claims have been relatively low and flat since February, with a modest spike in July (which is typical in July because auto manufacturers usually lay off workers as they retool their assembly lines). In the adjusted data, there is a huge spike in April which does not show up at all in the raw data. This was largely the result of earlier-than-expected auto layoffs. The seasonal factors expected the actual data to be weak in April, but instead it was higher than usual, so that turned into a large rise in the adjusted data.

In any event, the predictable seasonal events are now in the past, and we won't have another until later this year when workers hired to prepare for the Christmas season start getting laid off. What's happened so far this year is that all the confusion created as a result of volatile claims numbers has been much ado about almost nothing. Despite the headlines, claims have been fairly stable for most of the year; the economy is neither accelerating nor decelerating. It's steady (and slow) as she goes, although I think there is reason to expect activity to pick up somewhat in the months to come.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Nobody is proposing actual spending cuts

When the history of the Great Debt Limit Debate is written, one of the key villains will be the definition of "cut." For everyone who lives outside the halls of Congress, "cut" means to reduce. But inside Congress, "cut" means to spend less than your baseline projection of future spending. Since spending always tends to rise by at least the growth of nominal GDP, which has averaged about 5.5% for the past 30 years, the baseline that everyone compares their budget proposals to tends to project increased spending of about 5-6% per year.

Over the past 12 months the federal government has spent $3.56 trillion. A typical baseline would project spending to increase about 5.5% a year, reaching some $6 trillion a year by 2021 (budget scoring generally focuses on what happens over the next 10 years). That would equate to total expenditures of $48.4 trillion over the next decade. So when one party proposes to "cut" spending by, say, $4 trillion, what they really mean is that they propose to spend $44.4 trillion over the next 10 years instead of $48.4 trillion. The $4 trillion "cut" they are proposing actually works out to a 4% annual increase in spending, instead of a 5.5% annual increase in spending.

So even the most radical of "cuts" that are being proposed today would still allow government spending to increase by 4% a year. How hard or draconian is that?

I suspect the great majority of Americans would be stunned to realize that if we allowed government spending to increase by only 2% a year, then we could probably balance the budget in about 7 years, without any need to increase tax rates or actually cut anybody's spending. No real cuts and no real tax hikes are needed to balance the budget within a reasonable time frame. Why is there so much sound and fury surrounding this debate?

(My calculations assume that tax revenues as a percent of GDP rise naturally to about 18% of GDP over the next 7 years, which is close to the long-term average and the same level that was achieved a few years after the Bush tax cuts. Tax revenue as a % of GDP always rises during the expansion phase of a business cycle, and we know that the current level of tax rates can generate 18% of GDP if the economy is healthy.)

UPDATE: Prompted by reader "William" as to why it seems so hard for Congress to do something simple like cutting the growth rate of spending to 2% instead of 5.5%, I offer this explanation: The problem with cutting the growth rate of spending is that CBO scores this as a "cut", and the "cut" that would result from a 2% growth rate in spending would be on the order of $8.6 trillion. My guess is that no congressman or senator would want to be labeled as the guy who "cut" such a gigantic amount of spending. Think of all the kids who would starve, the old folks who would die from lack of medicine, etc. In short, it would be too easy for political opponents to brand the cutter as an evil madman, when in fact he was just trying to be reasonably prudent.

Over the past 12 months the federal government has spent $3.56 trillion. A typical baseline would project spending to increase about 5.5% a year, reaching some $6 trillion a year by 2021 (budget scoring generally focuses on what happens over the next 10 years). That would equate to total expenditures of $48.4 trillion over the next decade. So when one party proposes to "cut" spending by, say, $4 trillion, what they really mean is that they propose to spend $44.4 trillion over the next 10 years instead of $48.4 trillion. The $4 trillion "cut" they are proposing actually works out to a 4% annual increase in spending, instead of a 5.5% annual increase in spending.

So even the most radical of "cuts" that are being proposed today would still allow government spending to increase by 4% a year. How hard or draconian is that?

I suspect the great majority of Americans would be stunned to realize that if we allowed government spending to increase by only 2% a year, then we could probably balance the budget in about 7 years, without any need to increase tax rates or actually cut anybody's spending. No real cuts and no real tax hikes are needed to balance the budget within a reasonable time frame. Why is there so much sound and fury surrounding this debate?

(My calculations assume that tax revenues as a percent of GDP rise naturally to about 18% of GDP over the next 7 years, which is close to the long-term average and the same level that was achieved a few years after the Bush tax cuts. Tax revenue as a % of GDP always rises during the expansion phase of a business cycle, and we know that the current level of tax rates can generate 18% of GDP if the economy is healthy.)

UPDATE: Prompted by reader "William" as to why it seems so hard for Congress to do something simple like cutting the growth rate of spending to 2% instead of 5.5%, I offer this explanation: The problem with cutting the growth rate of spending is that CBO scores this as a "cut", and the "cut" that would result from a 2% growth rate in spending would be on the order of $8.6 trillion. My guess is that no congressman or senator would want to be labeled as the guy who "cut" such a gigantic amount of spending. Think of all the kids who would starve, the old folks who would die from lack of medicine, etc. In short, it would be too easy for political opponents to brand the cutter as an evil madman, when in fact he was just trying to be reasonably prudent.

A suggestion for Boehner and Reid

Fellows, at this point there is no way anyone is going to come up with a serious reform of our dysfunctional federal government before August 2nd, and I don't even want you to try. You can't change the course of our government with a deadline approaching and with false accusations and hyperbole polluting the airwaves. I hope you don't attempt something like what happened with Obamacare, where a 2,000 page bill was put together in the wee hours of the morning and nobody had a chance to read the fine print before it was passed. This is a debate that needs to be conducted in the open air, with plenty of time and discussion. It's not going to happen this week.

So why not just concede that you have reached an impasse, and that the only sensible thing to do is to increase the debt limit by enough to buy us time for more discussion. In fact, the issues you need to resolve are exactly the issues we should all be discussing next year as a national election approaches. Let's extend and continue these discussions, but let's remove the threat of default that is just making things worse.

So why not just concede that you have reached an impasse, and that the only sensible thing to do is to increase the debt limit by enough to buy us time for more discussion. In fact, the issues you need to resolve are exactly the issues we should all be discussing next year as a national election approaches. Let's extend and continue these discussions, but let's remove the threat of default that is just making things worse.

Capex update: moderate growth

New orders for capital goods fell slightly in June, but the more stable 3-mo. moving average rose 0.3% (this series is notorious for its monthly and quarterly volatility), and is up at a 9% annualized rate over the past six months. Nevertheless, there has been a slowdown in the past year, compared to the rapid growth of the first half of 2010, and this is consistent with a lot of other indicators of moderating activity, and with the slower reported growth of the first and (most likely) second quarters of this year. So there's not much new or helpful information in this series.

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Housing price update

This first chart shows the latest data for two different but remarkably similar indices of home prices. The Case Shiller index tracks the sale price of the same houses over time, and reports the average price of homes sold, and the Radar Logic index tracks the average cost per square foot of homes sold. While both are showing that prices have slipped a bit in the past year, prices today (actually, the latest data report the average of the three months ended in May) are almost identical to what they where in the early part of 2009. Thus, we have had two years of relative price stability in the housing market.

After adjusting for inflation, however, housing prices have fallen about 5% in the past two years. Real home prices are now about 39% below their 2006 peak. That's a significant price adjustment.

We can look at prices over a longer period thanks to the Case Shiller data which covers 10 major metropolitan areas (the top chart cover 20). This third chart is also adjusted for inflation.

Those looking for further significant declines in housing prices might like this chart, since it suggests that prices could fall back to their 1997 lows, which would imply a 32% decline from today's levels. That would be painful indeed.

On the other hand, this chart of real median existing home prices shows that prices today are about the same as they were in the late 1970s, and that prices haven't even increased in real terms by 1% a year over the past 40 years. (It seems reasonable that real home prices should tend to increase by at least some small amount over time, to reflect rising real incomes and a rising standard of living).

In my opinion, what all these charts show is that there is good reason to think that the "bubble" in housing prices that formed in the mid-2000s has disappeared, and that prices today are reasonable, give or take a little, compared to long-term historical trends. There is no compelling historical reason, in other words, to think that prices need to drop significantly from current levels. Moreover, new home construction has been far below the rate of new housing formations for several years now, so we know that the excess inventory of homes has declined significantly. Whatever slack is left in the housing market could quickly become used up by a combination of 1) moderate economic growth, 2) rising incomes, 3) rising inflation, and 4) new household formations. And of course with mortgage rates near record lows, the effective cost of a home today is quite low by historical standards, perhaps as low as it's ever been.

I continue to believe that we've seen the worst of the housing market, and that the next shoe to drop will be the surprising news that prices are starting to rise and residential construction is starting to improve.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Thinking twice about a possible Treasury downgrade

I was probably too cavalier this morning in my dismissal of the risks of a Treasury downgrade. In discussions over lunch today with my most excellent former colleagues, Steve and Ken, I came to appreciate the deep concerns that hover over the institutional bond market community. My point this morning was that a downgrade of US Treasury debt is essentially a downgrade of all debt—since Treasuries are the bedrock upon which all debt is priced—so a downgrade doesn't really mean much.

Their point, however, is that a downgrade of Treasury debt has huge and little-understood implications for many large institutional bond portfolios. To understand why, consider the case of a billion dollar bond portfolio that is currently underweight Treasuries, overweight MBS and corporate bonds, and skewed to lower-quality debt given the steepness of the credit curve. Given the steepness of the yield curve and the still-generous level of corporate spreads, overweighting MBS and corporates has been a very profitable strategy in recent years and promises to continue to be so. Moreover, such a strategy recognizes that Treasuries are very fully valued (and quite possibly overvalued), and thus minimizes a portfolio's exposure to rising Treasury yields. If a manager is even modestly optimistic on the economy's prospects, and if he believes that the Fed's accommodative monetary policy stance should, by making liquidity relatively abundant, result in relatively low default rates and facilitate economic growth, then positioning this portfolio at the low end of his client's acceptable credit quality range makes a lot of sense. (And isn't the Fed trying to encourage people to take on more risk?) In short, there are many good reasons for large, diversified, institutional portfolios to be structured today with a relatively low average credit quality.

But here's the catch: If Treasuries are downgraded, then a portfolio's average credit quality, assuming it holds at least some Treasuries, will fall. Even if the portfolio holds MBS and no Treasuries, one could argue that a downgrade of Treasuries perforce implies a downgrade of current-issue MBS, since their AAA rating depends crucially on the assumption that the implied Treasury guarantee of principal is bullet-proof. In short, if you downgrade Treasuries you downgrade just about everything, as I was arguing this morning.

But if you downgrade Treasuries and MBS, you need to understand that the average credit quality of our diversified, billion dollar portfolio will fall, and meaningfully. If a portfolio is currently at the low end of its acceptable average quality, a downgrade of Treasuries and MBS could quickly put it in violation of its credit quality guidelines. The solution to this problem illustrates the quandary that the bond market is very concerned about: The only way to bring the average quality of our billion dollar portfolio portfolio back up to its minimum required level, if Treasuries are downgraded, is to sell the cheapest bonds (e.g., the low-quality corporates) and buy the most expensive bonds (e.g., Treasuries). How would you like to call your billion dollar client and explain to him that as a result of the downgrade of Treasury bonds, of which you held very little or none because you think they are overvalued, you now have to buy more? And that in order to buy more Treasury bonds you have to sell the bonds that yesterday you thought were the cheapest and most attractive?

When this example is multiplied over the hundreds of billions and even trillions of dollars of diversified bond portfolios with strict quality guidelines, you suddenly realize that the bond market might theoretically be forced to dump massive quantities of low-quality bonds (thus raising the borrowing costs of hosts of struggling companies) in order to buy equally massive quantities of Treasury bonds (thus keeping Treasury yields very low), should Treasuries be downgraded. To drive home the absurdity of this, consider that the worse the deficit situation of the US becomes, the more our billion dollar bond portfolio would have to invest in Treasuries. This may sound surprising and even counterintuitive to bureaucrats, rating agencies, and the layman, but it would be eminently in keeping with The Law of Unintended Consequences, which is always lurking in the background, waiting to make fools of those who live by rigid rules and not by logic.

Memo to the bond market: it's past time to make quality guidelines more flexible.

Their point, however, is that a downgrade of Treasury debt has huge and little-understood implications for many large institutional bond portfolios. To understand why, consider the case of a billion dollar bond portfolio that is currently underweight Treasuries, overweight MBS and corporate bonds, and skewed to lower-quality debt given the steepness of the credit curve. Given the steepness of the yield curve and the still-generous level of corporate spreads, overweighting MBS and corporates has been a very profitable strategy in recent years and promises to continue to be so. Moreover, such a strategy recognizes that Treasuries are very fully valued (and quite possibly overvalued), and thus minimizes a portfolio's exposure to rising Treasury yields. If a manager is even modestly optimistic on the economy's prospects, and if he believes that the Fed's accommodative monetary policy stance should, by making liquidity relatively abundant, result in relatively low default rates and facilitate economic growth, then positioning this portfolio at the low end of his client's acceptable credit quality range makes a lot of sense. (And isn't the Fed trying to encourage people to take on more risk?) In short, there are many good reasons for large, diversified, institutional portfolios to be structured today with a relatively low average credit quality.

But here's the catch: If Treasuries are downgraded, then a portfolio's average credit quality, assuming it holds at least some Treasuries, will fall. Even if the portfolio holds MBS and no Treasuries, one could argue that a downgrade of Treasuries perforce implies a downgrade of current-issue MBS, since their AAA rating depends crucially on the assumption that the implied Treasury guarantee of principal is bullet-proof. In short, if you downgrade Treasuries you downgrade just about everything, as I was arguing this morning.

But if you downgrade Treasuries and MBS, you need to understand that the average credit quality of our diversified, billion dollar portfolio will fall, and meaningfully. If a portfolio is currently at the low end of its acceptable average quality, a downgrade of Treasuries and MBS could quickly put it in violation of its credit quality guidelines. The solution to this problem illustrates the quandary that the bond market is very concerned about: The only way to bring the average quality of our billion dollar portfolio portfolio back up to its minimum required level, if Treasuries are downgraded, is to sell the cheapest bonds (e.g., the low-quality corporates) and buy the most expensive bonds (e.g., Treasuries). How would you like to call your billion dollar client and explain to him that as a result of the downgrade of Treasury bonds, of which you held very little or none because you think they are overvalued, you now have to buy more? And that in order to buy more Treasury bonds you have to sell the bonds that yesterday you thought were the cheapest and most attractive?

When this example is multiplied over the hundreds of billions and even trillions of dollars of diversified bond portfolios with strict quality guidelines, you suddenly realize that the bond market might theoretically be forced to dump massive quantities of low-quality bonds (thus raising the borrowing costs of hosts of struggling companies) in order to buy equally massive quantities of Treasury bonds (thus keeping Treasury yields very low), should Treasuries be downgraded. To drive home the absurdity of this, consider that the worse the deficit situation of the US becomes, the more our billion dollar bond portfolio would have to invest in Treasuries. This may sound surprising and even counterintuitive to bureaucrats, rating agencies, and the layman, but it would be eminently in keeping with The Law of Unintended Consequences, which is always lurking in the background, waiting to make fools of those who live by rigid rules and not by logic.

Memo to the bond market: it's past time to make quality guidelines more flexible.

The debt limit will be raised

There's a lot of political posturing going on in Washington, but by the end of the week we are almost certain to see an increase in the debt limit, because neither party can afford to fail on that issue. What is not clear, however, are three things: 1) how much the limit will be raised (will it be a short-term fix, or a fix that will take us beyond next year's elections?), 2) how much spending will be cut (spending will definitely be cut), and 3) whether taxes will increase. On the latter point, I see almost no chance that tax rates will increase; if higher revenues are part of the deal, the money will come as the result of cleaning up the tax code (eliminating deductions), and from a stronger economy. The economy is not strong enough to sustain tax rate increases, and everybody knows that.

So by the time the dust settles later this week, there's a very good chance that we will see Washington take action to fix our biggest problem, which is too much spending. The debt limit debate has served a good purpose, which has been to focus the public's mind on the huge growth in government spending that has left us with a staggering burden of debt in just a few short years. It's about time. Fiscal policy was on an unsustainable course, and now it looks like a course correction is imminent. The problem won't be completely solved, of course, because it will take years to fix. But next year's elections will give the people ample time and opportunity to think about our priorities. I suspect that the ongoing popularity of the Tea Party reflects a widespread and growing belief that government has become too large and must be cut back. If that's the case, then there is plenty of room for optimism.

Whether US debt is downgraded or not is almost a side-show compared to the bigger, long-term issue of the size of government. A downgrade doesn't seem very likely, but if it were to occur it would just add to the pressure to cut spending, a process that is already underway.

But all this is hardly news, and I only point out the obvious. A quick glance at the bond market, where 10-yr Treasuries are trading at 3%, is enough to know that the market is not at all concerned about the possibility that the US might actually default on its debt obligations.

UPDATE: This quotation from Thomas Babington Macaulay seems to fit perfectly the emerging mood of the people:

HT: Don Boudreaux

So by the time the dust settles later this week, there's a very good chance that we will see Washington take action to fix our biggest problem, which is too much spending. The debt limit debate has served a good purpose, which has been to focus the public's mind on the huge growth in government spending that has left us with a staggering burden of debt in just a few short years. It's about time. Fiscal policy was on an unsustainable course, and now it looks like a course correction is imminent. The problem won't be completely solved, of course, because it will take years to fix. But next year's elections will give the people ample time and opportunity to think about our priorities. I suspect that the ongoing popularity of the Tea Party reflects a widespread and growing belief that government has become too large and must be cut back. If that's the case, then there is plenty of room for optimism.

Whether US debt is downgraded or not is almost a side-show compared to the bigger, long-term issue of the size of government. A downgrade doesn't seem very likely, but if it were to occur it would just add to the pressure to cut spending, a process that is already underway.

But all this is hardly news, and I only point out the obvious. A quick glance at the bond market, where 10-yr Treasuries are trading at 3%, is enough to know that the market is not at all concerned about the possibility that the US might actually default on its debt obligations.

UPDATE: This quotation from Thomas Babington Macaulay seems to fit perfectly the emerging mood of the people:

Our rulers will best promote the improvement of the nation by strictly confining themselves to their own legitimate duties, by leaving capital to find its most lucrative course, commodities their fair price, industry and intelligence their natural reward, idleness and folly their natural punishment, by maintaining peace, by defending property, by diminishing the price of law, and by observing strict economy in every department of the state. Let the Government do this: the People will assuredly do the rest.

HT: Don Boudreaux

Friday, July 22, 2011

The great debate: more taxes vs. less spending

As Congress debates whether our massive budget deficits should be reined in by raising taxes or by cutting spending, it seems appropriate to republish the above chart. What it shows is that the top 10% of income earners paid 70% of all income taxes in 2008 (most recent data available). Moreover, it shows that the share of total taxes paid by the "rich" has increased substantially since the early 1980s, despite a huge reduction in the top marginal tax rate. If that is not a vindication of the Laffer Curve, I don't know what is. What the chart doesn't show is that the top 5% of income earners paid more in income tax than the other 95%, and roughly half of all workers pay no income tax. In short, the federal income tax burden is being shouldered by a small minority of taxpayers. This minority is now being subject to a "tyranny of the majority," in which the majority of those in Congress are trying to decide whether the minority of workers should effectively pay all the bills for everyone. In that context it's gratifying to note that according to a CNN poll, "two-thirds of voters favor the idea of tying a raise in the debt ceiling to spending caps and a balanced budget amendment." Congress may be out of touch with the people on this one.

As Milton Friedman taught us, the burden of government is not measured by taxes, but by spending. Whether a deficit is financed by raising taxes or by borrowing more, in the end, resources are taken from the private sector and spent by the public sector. That transfer imposes a burden on the economy since the public sector almost always spends money less efficiently than the private sector. So not only is the debate about who should pay for the huge increase in spending over the past several years, but also whether government spending should continue at such high levels.

UPDATE: For the sake of perspective, I am republishing the following charts which show the different ways in which the federal government taxes and spends (currently at an annual rate of almost $3.6 trillion) our money:

PIIGS update: Greece to get a voluntary debt restructuring

The top chart shows the history of 2-yr sovereign yields for the PIIGS countries, while the bottom chart shows the rate on 5-yr Greek Credit Default Swaps. The deal being finalized in Europe that combines more aid to Greece with the "voluntary" participation of private bondholders in a debt exchange (aka restructuring) has had a significant impact on these sensitive indicators of default risk. It's not that a Greek default now has become less likely, it's that the magnitude of the default will be much less than the market feared. And that, in turn, has reduced the likelihood of a sovereign debt default contagion. It's interesting that the ISDA (the International Swaps & Derivatives Association that determines whether a "credit event" has occurred that would in turn trigger the payment of by those who have sold CDS) has indicated that a voluntary restructuring would not necessarily qualify as a credit event.

As this chart of 2-yr swap spreads shows, the degree of systemic risk in Europe hasn't changed much despite the restructuring deal. It's uncomfortably high, but not seriously so. Some banks could be in trouble, but swap spreads of just under 70 bps don't point to an untenable or out-of-control financial meltdown. In short, Europe is dealing with the PIIGS problem in a variety of ways and is likely to survive largely intact. Conceivably, this could all turn out to be a nonevent.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

John Taylor nails it

Don't miss John Taylor's article in today's WSJ: "The End of the Growth Consensus." I think he summarizes quite nicely the reasons for why the economy is mired in a slow-growth recovery. It has nothing to do with partisan politics, and everything to do with policies that just don't make sense. Here's an excerpt, but please read the whole thing and pass it along:

In my view, the best way to understand the problems confronting the American economy is to go back to the basic principles upon which the country was founded—economic freedom and political freedom. With lessons learned from the century's tougher decades, including the Great Depression of the '30s and the Great Inflation of the '70s, America entered a period of unprecedented economic stability and growth in the '80s and '90s.

Economic policy in the '80s and '90s was decidedly noninterventionist, especially in comparison with the damaging wage and price controls of the '70s. Attention was paid to the principles of economic and political liberty: limited government, incentives, private markets, and a predictable rule of law. Monetary policy focused on price stability. Tax reform led to lower marginal tax rates. Regulatory reform encouraged competition and innovation. Welfare reform devolved decisions to the states. And with strong economic growth and spending restraint, the federal budget moved into balance.

As the 21st century began, many hoped that applying these same limited-government and market-based policy principles to Social Security, education and health care would create greater opportunities and better lives for all Americans.

But policy veered in a different direction. Public officials from both parties apparently found the limited government approach to be a disadvantage, some simply because they wanted to do more—whether to tame the business cycle, increase homeownership, or provide the elderly with better drug coverage.

And so policy swung back in a more interventionist direction, with the federal government assuming greater powers. The result was not the intended improvement, but rather an epidemic of unintended consequences—a financial crisis, a great recession, ballooning debt and today's nonexistent recovery.

The change in policy direction did not occur overnight. We saw increased federal intervention in the housing market beginning in the late 1990s. We saw the removal of Federal Reserve reporting and accountability requirements for money growth from the Federal Reserve Act in 2000. We saw the return of discretionary countercyclical fiscal policy in the form of tax rebate checks in 2001. We saw monetary policy moving in a more activist direction with extraordinarily low interest rates for the economic conditions in 2003-05. And, of course, interventionism reached a new peak with the massive government bailouts of Detroit and Wall Street in 2008.

Since 2009, Washington has doubled down on its interventionist policy. The Fed has engaged in a super-loose monetary policy—including two rounds of quantitative easing, QE1 in 2009 and QE2 in 2010-11. These large-scale purchases of mortgages and Treasury debt did not bring recovery but instead created uncertainty about their impact on inflation, the dollar and the economy. On the fiscal side, we've also seen extraordinary interventions—from the large poorly-designed 2009 stimulus package to a slew of targeted programs including "cash for clunkers" and tax credits for first-time home buyers. Again, these interventions did not lead to recovery but instead created uncertainty about the impact of high deficits and an exploding national debt.

Unfortunately, as the recent debate over the debt limit indicates, narrow political partisanship can get in the way of a solution. The historical evidence on what works and what doesn't is not partisan. The harmful interventionist policies of the 1970s were supported by Democrats and Republicans alike. So were the less interventionist polices in the 1980s and '90s. So was the recent interventionist revival, and so can be the restoration of less interventionist policy going forward.

A deficit reduction bill should push interest rates higher

Markets got excited yesterday at the prospect that Congress may be closing in on a bipartisan deficit reduction bill. 30-yr Treasury yields fell 12 bps, as investors reasoned that a reduction in federal debt issuance would lead to higher prices for Treasury debt. (Much of that drop in yields has been reversed so far today.)

I think this is one of those times when the bond market's initial reaction to some new and important development is wrong, or at least not well thought out.

To understand why, it is important to realize that yields on Treasury notes and bonds are fundamentally determined by inflation and inflation expectations. Inflation expectations, in turn, can be impacted by the market's perception of the economy's strength, because the market, and the Fed, believe that strong growth can add to inflation pressures, while weak growth creates deflationary pressures.

It's also important to understand that every bond issued in dollars is priced relative to Treasuries of a comparable maturity. Since Treasuries are the risk-free bedrock of the dollar-based bond market, non-Treasury securities have to pay a higher yield, or spread. That spread can change, of course, but if Treasury yields rise significantly, then it's a safe bet that the yields on all bonds will rise significantly.

The larger point here is that a change in the yield on Treasuries affects the yields on all bonds. Treasuries do not exist in isolation.

Our current $1.3 trillion federal deficit is a fairly large percentage of the $9.7 trillion of Treasury debt held by the public (about 13.5%), but the marginal borrower (in this case the U.S. government) does not set the price of the outstanding stock of U.S. debt, which is more than $30 trillion. Even very large $2 trillion deficits would have little impact on the level of bond yields, because the new supply of bonds would still be only a small fraction (6-7%) of all the investment-grade and high-yield bonds outstanding in the U.S. market. And I'm not even considering the more than $30 trillion in liquid, non-U.S. bonds outstanding in the world. Let me hasten to add that new Treasury issuance need not have any direct impact on inflation fundamentals, unless the Fed takes action to expand the money supply by more than the world desires.

Whether the federal government borrows $2 trillion or $1 trillion in the next year is not going to have much of an impact on the level of interest rates, taken in isolation, because the outstanding stock of bonds is orders of magnitude bigger. What could have a meaningful impact on interest rates, however, is how meaningful the package of spending cuts turns out to be. Many worry that a big cut in spending would weaken the economy, and that in turn would lead to lower inflation and lower interest rates.

But I think that a big cut in future spending would have a positive impact on the economy, since it would free up resources that can be better utilized by the private sector, and, by reducing future deficits, it would greatly increase the expected after-tax returns to investment. Combined, this could prove to be a powerful stimulus to growth. And so I think that upon reflection, a serious debt reduction package would eventually be perceived by the market to be good for the economy and therefore "bad" for the bond market, and that would mean higher, not lower yields.

I think this is one of those times when the bond market's initial reaction to some new and important development is wrong, or at least not well thought out.

To understand why, it is important to realize that yields on Treasury notes and bonds are fundamentally determined by inflation and inflation expectations. Inflation expectations, in turn, can be impacted by the market's perception of the economy's strength, because the market, and the Fed, believe that strong growth can add to inflation pressures, while weak growth creates deflationary pressures.

It's also important to understand that every bond issued in dollars is priced relative to Treasuries of a comparable maturity. Since Treasuries are the risk-free bedrock of the dollar-based bond market, non-Treasury securities have to pay a higher yield, or spread. That spread can change, of course, but if Treasury yields rise significantly, then it's a safe bet that the yields on all bonds will rise significantly.

The larger point here is that a change in the yield on Treasuries affects the yields on all bonds. Treasuries do not exist in isolation.

Our current $1.3 trillion federal deficit is a fairly large percentage of the $9.7 trillion of Treasury debt held by the public (about 13.5%), but the marginal borrower (in this case the U.S. government) does not set the price of the outstanding stock of U.S. debt, which is more than $30 trillion. Even very large $2 trillion deficits would have little impact on the level of bond yields, because the new supply of bonds would still be only a small fraction (6-7%) of all the investment-grade and high-yield bonds outstanding in the U.S. market. And I'm not even considering the more than $30 trillion in liquid, non-U.S. bonds outstanding in the world. Let me hasten to add that new Treasury issuance need not have any direct impact on inflation fundamentals, unless the Fed takes action to expand the money supply by more than the world desires.

Whether the federal government borrows $2 trillion or $1 trillion in the next year is not going to have much of an impact on the level of interest rates, taken in isolation, because the outstanding stock of bonds is orders of magnitude bigger. What could have a meaningful impact on interest rates, however, is how meaningful the package of spending cuts turns out to be. Many worry that a big cut in spending would weaken the economy, and that in turn would lead to lower inflation and lower interest rates.

But I think that a big cut in future spending would have a positive impact on the economy, since it would free up resources that can be better utilized by the private sector, and, by reducing future deficits, it would greatly increase the expected after-tax returns to investment. Combined, this could prove to be a powerful stimulus to growth. And so I think that upon reflection, a serious debt reduction package would eventually be perceived by the market to be good for the economy and therefore "bad" for the bond market, and that would mean higher, not lower yields.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

The 2 1/2 year bottom in housing starts

Housing starts have been incredibly weak for the past 2 1/2 years, much weaker than at any time since records were first kept beginning back in 1959. As a result, residential construction has fallen to a record-low 2% of GDP, after averaging around 5% since WWII. During this extended and bitterly painful construction collapse, the economy has recovered from a severe recession, personal income has grown 8%, retail sales are up 15%, after-tax corporate profits have surged 38%, Apple stock has more than tripled, households' net worth has risen by over $8 trillion, and the U.S. population has increased by about 6 million, among a host of other notable milestones. Housing starts are almost certainly well below the rate of new household formations, so every month that starts remain at currently depressed levels puts us one month closer to an inevitable boom in new home construction, since the excess inventory of homes is shrinking daily. The outlook for housing is thus likely to be stable at the least, and eventually extremely positive.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Bond market sees very weak growth & higher inflation

The yield on 2-yr Treasuries is once again at rock-bottom levels (0.36%). This yield is a window to the market's expectations for Fed policy, since it can be equated to the expected average Fed funds rate over the next two years. With Fed funds currently at a mere 0.1%, the market obviously doesn't expect much in the way of Fed tightening over the next two years. Those expectations, in turn, flow directly from the market's collective belief that the economy is going to be dreadfully weak for a long time, thus forcing the Fed to remain ultra-accommodative. Weak growth and low yields, in other words, go hand in hand; as the above chart illustrates.

Many observers argue that the extremely low level of short-term Treasury yields is also a sign that the market expects very low inflation or deflation, but the chart below shows that in fact just the opposite is true. The bond market's inflation expectations have been on the rise, as reflected in a steeper slope between 10- and 30-yr Treasuries, and a rise in the 5-yr, 5-yr forward expected inflation rate that is embedded in Treasury and TIPS prices.

The message of the bond market also illustrates the policy conundrum that confronts the Fed: despite the most accommodative monetary policy ever, the economy is refusing to respond. The knee-jerk reaction of bureaucrats and politicians is to apply yet more stimulus when stimulus fails to work, but we've now had several years of super-accommodative monetary policy and massive fiscal spending stimulus, to no apparent effect. All we have to show for this exercise in public sector hubris is rising inflation expectations and moribund growth expectations. Which is not surprising to me, since as a supply-sider I have always thought that growth can only come from hard work, investment, and entrepreneurial risk-taking. The proper role of government is not to direct the economy's efforts, but to provide for essential services, uphold the rule of law, protect private property, and protect the purchasing power of the currency, among other (limited) things.

So the right thing to do is not to do more of the same, but to reverse course. Tighter monetary policy would reduce inflation expectations, strengthen the dollar, punish the gold and commodity speculators, and restore investors' confidence. Reduced government spending would free up resources for the private sector to exploit and increase investment, since it would automatically reduce future expected tax burdens—and increase the expected after-tax return to risk-taking.

The bond market is trying hard to send its message to Washington. Is anyone listening?

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Carmageddon, free markets, and the PIIGS crisis

Residents of the Los Angeles metropolitan area have known for almost two months that this weekend would be our worst traffic nightmare: the two-day closing of a key stretch of the 405 freeway. Signs have been posted everywhere with the warning, even as far away as San Diego. And what happened? Absolutely nothing. In fact, traffic hasn't been so good for as long as I can remember. Why? Because almost everyone stayed home to avoid the traffic.

If you want a reason to not worry about the looming PIIGS sovereign debt crisis, this is it.

When people have access to information and an incentive to act on it, they will.

The world has known since April of last year that the governments of Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain were in a bind and might not be able to meet their outsized debt obligations. For many months markets have been bombarded with the news that if one of the PIIGS defaults, it could trigger a default contagion that could bring down other PIIGS and perhaps the entire European banking system. Only those who have been in a coma could not know by now that this has the potential to be Debt Armageddon.

How many people are likely to be blindsided by a Greek default? Not many, I think, because the price of Greek debt already reflects something like a 40% default "haircut." How seriously could European banks be affected by a default? It would be painful, but it's quite likely to be far less than a catastrophe, as suggested by 2-yr Euro swap spreads of 70 bps. Would a PIIGS default present a serious problem for the U.S. economy? Not likely at all, as suggested by 2-yr U.S. swap spreads of 30 bps.

The reality of a PIIGS default is likely to be much less than the world fears, because the world has had a long time to prepare for it and most of the ill effects have already been priced in by the market.

If you want a good example of how powerful free markets can be, this is it.

When people have access to information and an incentive to act on it, they will.

The world has known since April of last year that the governments of Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain were in a bind and might not be able to meet their outsized debt obligations. For many months markets have been bombarded with the news that if one of the PIIGS defaults, it could trigger a default contagion that could bring down other PIIGS and perhaps the entire European banking system. Only those who have been in a coma could not know by now that this has the potential to be Debt Armageddon.

How many people are likely to be blindsided by a Greek default? Not many, I think, because the price of Greek debt already reflects something like a 40% default "haircut." How seriously could European banks be affected by a default? It would be painful, but it's quite likely to be far less than a catastrophe, as suggested by 2-yr Euro swap spreads of 70 bps. Would a PIIGS default present a serious problem for the U.S. economy? Not likely at all, as suggested by 2-yr U.S. swap spreads of 30 bps.

The reality of a PIIGS default is likely to be much less than the world fears, because the world has had a long time to prepare for it and most of the ill effects have already been priced in by the market.

Friday, July 15, 2011

Money supply growth alert (cont.)

Over the most recent two-week period, the M2 measure of money supply has surged by $165 billion. Such rapid and sizable growth is highly unusual, and has happened in the past only during periods of panic-driven demand for cash liquidity (e.g., following 9/11 and in the wake of the financial market panic of late 2008). As I noted in my first post on this subject, normal M2 growth would be about $10 billion per week. From the Fed's data, we see that about $100 billion of this growth has come from increased savings deposits at commercial banks, $55 billion has come from increased demand deposits, and all the growth has occurred in the non-M1 portion of M2. What's going on? It's tempting to think that this is somehow a reflection of the end of QE2 and the beginning of Treasury's need to juggle funds since the debt limit is approaching, but I honestly don't know. Stay tuned.

UPDATE: (Aug. 4th) It now appears that this surge in M2 was the product of panic-driven demand for safe-haven cash as Europeans attempted to escape the potential contagion of PIIGS defaults.

PIIGS update

The message of these three charts is that a PIIGS default/restructuring is highly likely to occur, but that it does not pose a serious threat to Eurozone banks or the Eurozone economy.

The first chart shows the yield on 2-yr sovereign debt for each of the PIIGS countries. The extremely high level of yields on Greek, Irish, and Portuguese bonds is the market's way of saying that a significant default is highly likely to occur. The second chart shows Eurozone swap spreads and U.S. swap spreads. With swap spreads being a good proxy for systemic risk and the default risk of large banks, we can infer that the market assigns a very low level of risk to the U.S. economy and banking system, and a moderate level of risk to the Eurozone economy and banking system. Note that the probability of default in PIIGS countries has never been higher than it is today, but Euro swap spreads are still lower than they were in April 2010, when the Greek debt problem first surprised the world. The third chart is Europe's equivalent of our Dow and S&P 500: the Euro Stoxx 50 Index. What it says is that the Eurozone economy has been in muddle-through mode ever since the Greek debt crisis broke. Muddle-through, but not collapse by any means.

Today we received the news that a stress test of European banks found that only 8 would likely fail to survive a worst-case scenario—a significant economic slowdown. Furthermore, these banks had a combined capital shortfall of only $3.5 billion, which is a relative drop in the global capital market bucket. Whether or not you believe this was a serious or rigorous test, it does jibe with the level of swap spreads. Both are saying that yes, there are problems, but these problems are not likely to bring about widespread contagion or financial market collapse. Since the sovereign debt problem has been around for well over a year, it is undoubtedly the case that banks collectively have taken steps to shore up their capital and to reduce their exposure to the sovereigns most likely to default. It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that the market has enforced enough discipline on the system, and enough repricing and restructuring, to render a catastrophe highly unlikely.

As I note before in a post about the consequences of debt defaults, much of the bad news has already been priced in, and it is evident in the fact that the Eurozone economy has been growing at a disappointingly slow pace, similar to what the U.S., with its extraordinary deficits, is experiencing. Defaults are symptomatic of debt that has been used to finance wasteful or inefficient spending, and in this case of economies that have used scarce resources ineffectively. Massive, debt-financed government spending cannot stimulate an economy, but it can stifle the ability of the private sector to generate meaningful growth.

Bond market on the horns of a dilemma

Inflation and expected inflation are arguably the major determinants of interest rates. If the bond market appears to react to signs of growth, as it often does, then that is because the bond market—and the Fed—continue to think that growth and inflation are linked: i.e., more growth increases inflation risk, while less growth reduces it. We are now living in interesting times, however, because growth has been unusually weak and the so-called "output gap" (the amount of excess capacity, or the amount by which the economy is operating below its potential) has been huge—currently about 10% according to my calculations. Yet inflation by all measures has been rising. The bond market wants to rally, given how weak the economy is, but it is bumping up against the reality of higher inflation, as the chart above suggests.

Core inflation over the past six months is running at a 2.5% annualized rate. That doesn't sound like much, but as the top chart suggests, when core CPI is 2.5%, 10-yr Treasury yields tend to be in the neighborhood of 4.5%, and a 2% spread between inflation and bond yields is close to the long-term average. If long-term trends reassert themselves, Treasury yields could rise significantly. So the bond market is essentially caught on the horns of a dilemma: the lure of weak growth (perhaps made weaker by sovereign defaults) vs. the reality of rising inflation. We haven't seen a test of the Phillips Curve theory of inflation like this for a long time. The last time I remember such a test was in the late 1990s, when the economy was booming, and the Fed was fearful that the economy was "overheating" and inflation would rise. By the time the dust had settled, around 2002-2003, we realized that inflation had almost fallen enough to produce deflation. I think that when the dust finally settles on the current environment, we will see inflation rising some more, and Treasury yields rising by a lot more.

In the meantime, there are two clear facts about inflation: 1) it has been extraordinarily volatile over the past 10 years, and 2) by all measures inflation has moved higher in the past year. At the very least, the volatility of inflation is a problem since it leaves the world uncertain as to what is really going on. The fact that inflation has risen, despite the very sluggish recovery and the existence of tons of excess capacity, is also problematic, because it directly challenges the theory that says inflation should be very low because the economy is so weak. Both of these realities weigh heavily on Treasury note and bond prices.

Thursday, July 14, 2011

Inflation still alive and well at the producer level

June Producer Price Inflation came in a bit stronger than expected, despite the biggest decline in energy prices in two years. Although the headline PPI fell by 0.4% during the month, the more important number is the core PPI, which rose by 0.3%, vs. an expected rise of 0.2%. On a six-month annualized basis, the headline number is now 8.1%, and the core number is 3.7%. The core PPI hasn't risen this fast since April 1991.

That core prices are rising is a reflection of the strong gains in commodity prices that are making their way through the production pipeline. It is also a reflection of the fact that monetary policy is quite accommodative, since it is not trying to fight higher energy prices. If policy were tight, then higher energy prices would have forced declines in non-energy prices, but that is not happening. Since producer prices are more sensitive to commodities than the CPI, the PPI is thus like the canary in the coal mine, predicting higher inflation on the way in the CPI.

It's also important to note that rising inflation is showing up at the producer level, despite the substantial amount of economic "slack" that presumably exists in the U.S. economy. This casts doubt on the widely-held belief, which the Fed shares, that today's large output gap will be an important restraining force on inflation.

Much ado about nothing (cont.)

Today, seasonally adjusted claims for unemployment fell "unexpectedly," and the market is responding positively, just as I have been predicting for weeks. But in fact, all that has happened is that not as many people are getting laid off in the auto industry in July as the seasonal factors expected. That's because they were laid off last April instead.

The first chart above shows the seasonally adjusted level of claims, which have declined in July. The second chart shows the actual level of claims, which for the first time this year has risen meaningfully. Seasonal factors expected claims to rise even more, much as they did at this time last year, so they subtract from the actual number.

Whatever you might think is actually happening to the real economy, what this shows is that seasonal adjustment factors can actually be wrong, in the sense that the economy doesn't always behave as expected. Sometimes you have to be skeptical of jobs numbers (in particular the June employment numbers released last week). The market and the headlines are somewhat excited about today's claims number, but I'm not. I think it's just payback for the "unexpected" increase in claims last April, when auto layoffs happened earlier than expected. The reality is that the economy remains in a slow-growth recovery, and any pickup that is suggested by the claims numbers is illusory.

The first chart above shows the seasonally adjusted level of claims, which have declined in July. The second chart shows the actual level of claims, which for the first time this year has risen meaningfully. Seasonal factors expected claims to rise even more, much as they did at this time last year, so they subtract from the actual number.

Whatever you might think is actually happening to the real economy, what this shows is that seasonal adjustment factors can actually be wrong, in the sense that the economy doesn't always behave as expected. Sometimes you have to be skeptical of jobs numbers (in particular the June employment numbers released last week). The market and the headlines are somewhat excited about today's claims number, but I'm not. I think it's just payback for the "unexpected" increase in claims last April, when auto layoffs happened earlier than expected. The reality is that the economy remains in a slow-growth recovery, and any pickup that is suggested by the claims numbers is illusory.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Federal budget update

Here's an update of the federal budget situation. It's still in awful shape, but on the margin things have improved a bit. Spending growth has slowed, revenues continue to grow faster than spending, and the deficit has consequently shrunk a bit.

With all the talk in Washington about the need for higher taxes, I note that federal revenues have grown about 9% in the past year. That's what usually happens during a recovery, as more people return to work, incomes rise, corporate profits grow, and capital gains get realized. It doesn't take higher tax rates to get more revenue, it just takes a bigger and stronger economy. Considering that the economy has been recovering a pace that is definitely subpar, 9% revenue growth is actually pretty impressive. If we could get the economy to grow at 5% or better, we would probably see a huge pickup in tax revenues.

The biggest problem, therefore, is spending. Spending is very elevated by any measure, and it will only balloon further if current law and programs are unchanged (social security and Obamacare promise to be real budget-busters). As I've argued repeatedly, excessive government spending is likely one of the chief causes of a disappointingly slow recovery. Cutting back spending should be the top priority, and from what I see of the goings-on in Washington and the opinion polls, most people understand this. Higher tax rates are not only unnecessary, they could easily jeopardize the recovery by reducing the after-tax incentives to work and invest.

Gold and commodity prices thrive on PIIGS and growth

Today gold hit a new all-time high against the dollar and yesterday it made a new high against the euro. What's driving gold higher? Gold continues to be a haven for those who worry about the health of the world's financial markets (e.g., the eurozone sovereign debt crisis), and it continues to benefit from the ultra-low interest rates and accommodative monetary policies of most of the world's central banks (with the Bank of Japan being the notable exception). Gold is a safe-haven play, and it is an inflation play. That's the way it's always been with gold.

As this next chart shows, gold has a tendency to lead commodity prices, so the continued strength in gold prices suggests we will see a renewed rise in commodity prices, after their recent selloff. In fact, as the chart below of a popular index of commodity futures prices shows, many commodities have already recovered much of their recent decline. It's the non-speculative type of commodity (many of which are in the CRB Spot index charted above) that have yet to recover, but at this point it's likely they will.

The action combined action in gold and commodity futures is a good indication that although investors are concerned about the risk of a PIIGS default, the global economy is not being impacted much, if at all, by the recent soft patch in the U.S. and the market's jitters. As the chart below shows, China's economy has grown by a massive 9.5% in the past year, and India's economy has been growing by 7-8% of late. Global trade is growing at strong double-digit rates, and commodity prices are trading very near all-time highs in almost all currencies.

Despite all the concerns out there, Euro swap spreads are still substantially below crisis levels, and U.S. swap spreads are perfectly normal. At the very least we can say that there does not appear to be any shortage of global demand, and no shortage of money. If there were, commodities would be a whole lot weaker, swap spreads and implied volatility would be on the moon, and equities markets would be collapsing.

To put the looming PIIGS debt default crisis in perspective, consider that the market value of global equity markets is north of $50 trillion, and the liquid global bond market (investment grade and high yield) totals over $60 trillion, according to the Lehman/Merrill Lynch bond data. Given that as a backdrop, it's hard to get overly concerned about the increasing likelihood that a few hundred (or even several hundred) billion worth of PIIGS debt—less than 1% of the value of outstanding global bonds—is likely to be written off. Especially since this problem has not exactly snuck up on unsuspecting market. The PIIGS crisis first surfaced over a year ago, so markets have had plenty of time to adjust prices and investors have had plenty of opportunities to reduce unwanted exposure.

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

More news which confirms the soft patch

The trade deficit expanded by more than expected in May, thanks mainly to higher petroleum prices, but as Brian Wesbury notes, oil prices fell in June so this should wash out and probably have little impact on second quarter GDP. But the contribution of trade to GDP is not as important as the ongoing, strong gains in exports, which have been growing at a 15-20% annual rate for the past two years and have surpassed their pre-recession high. This is very impressive, and good evidence that the U.S. economy is still among the world's most dynamic—strong export growth is helping to offset the weakness in finance and construction. It also reinforces the fact that global economic activity remains strong.

The UCLA/Ceridian Pulse of Commerce Index has been making slow upward progress for the past six months or so, providing more confirmation that indeed the economy has been in a "soft patch."

Monday, July 11, 2011

Debt musings and misconceptions

The world is obsessed with the problem of too much debt and the threat it poses to the civilized world. Greece is very likely to default on its debt, and so are Ireland and Portugal. Meanwhile, the U.S. wrestles with its own burden of debt. Total outstanding debt owed by the U.S. government to the public now stands at $9.75 trillion, or about 64% of GDP. That’s the highest level of federal debt relative to the economy since the early 1950s, when the U.S. government was working off its huge debt (well over 100% of GDP) incurred while fighting WW II. If the federal deficit continues at the current level of 9-10% of GDP, total debt will exceed 70% of GDP one year from now, and eventually it could exceed GDP.

Does all this debt and its attendant problems mean the economic outlook is inescapably bleak? Will PIIGS defaults result in a collapse of the Eurozone banking system? Will debt default contagion bring about another global recession? Will debt defaults intensify lingering deflationary pressures? The short answer is that most of the bad effects of too much debt have already happened.

Debt has certainly become problematic, but the threat it poses to the world is likely being exaggerated. That’s because there are a number of popular misconceptions about debt, and because many ignore that the market has already factored in the likely consequences of defaults.

Debt is a zero-sum game, since one man’s debt is another man’s asset. Debt is an agreement between two parties to exchange cash now with a reversal of that exchange, plus interest, in the future. If the borrower fails to repay his debt (i.e., he defaults), then the borrower benefits by being relieved of some or all of his debt service obligations, and the lender suffers by not receiving some or all of his expected cash flows. Part of the interest the lender charges the borrower goes to offset the risk of default.

Debt payments by a borrower are not equivalent to flushing money down the toilet. The money borrower B pays to lender A is money that A will spend on something else. The amount of money available to the economy doesn’t change when debt is serviced or paid off. Demand doesn’t change, money simply changes hands. Similarly, the issuance of new debt does not create new demand. When A loans money to B, A must spend less in order for B to spend more.

Credit expansion is not the same as money creation. Central banks, not credit markets, control the amount of money in an economy. They typically do this by targeting the price of money (e.g., short-term interest rates), and that in turn increases or decreases banks’ ability to lend, and increased bank lending is what leads to new money creation. Credit expansion does not create any new money because the issuance of new debt only causes existing money to change hands.

Credit outstanding can grow faster than the amount of money in an economy without there being any inflationary consequences, because credit does not create new money or new demand; it simply redistributes existing money. Similarly, credit contraction can occur without there being any decline in overall output or any deflation, provided the central bank is properly overseeing the amount of money in the economy. Credit contraction, aka deleveraging, is a sign of increased money demand, which should be offset by an increased supply of money. The Federal Reserve has been doing exactly this with its quantitative easing program: responding to the private sector’s desire to reduce its debt burdens. That's why quantitative easing to date has not been inflationary.

Borrowing with new debt can be a good thing for both parties to the transaction, provided borrower B spends the money that lender A saved on something productive. Investing in productive assets or activities generates the cash flow that is needed to pay the interest on the debt. Debt can be a drag on growth, however, if B spends the money on something unproductive. For example, Greece has borrowed hundreds of billions over the years, in part to fund generous retirements for people who retired at a relatively young age. Greece now finds that its economy hasn't grown enough to generate the cash flows it needs to repay its debt. The damage has been done, and no amount of EU assistance to Greece can alter the fact that Greece in effect “wasted” the money and has nothing to show for it. Borrowing money only to spend it on unproductive things is already reflected in the slow growth of the Greek economy; Greece has been squandering its scarce resources. Markets now understand that a default is highly likely and have already priced in a significant Greek default.

A nation that defaults on its debt does not necessarily need to suffer a decline in its GDP or national income. GDP is determined primarily by the number of people working and the productivity of their labors. Debt defaults and/or restructurings can lead to positive outcomes if steps are taken to increase productivity. Relieved of some of the burden of its debt, but much less likely to qualify for new loans, Greece could move forward by cutting spending, trimming retirement benefits, and encouraging new investment and business formation. Many unproductive retirees may need to go back to work, and they might be encouraged to do so if enough new and attractive jobs are created.

If Greece's creditor banks fail to receive their expected cash flows, many may go out of business. But that won't change the cash flows and the incomes that are being generated by all the people working in the world. The PIIGS may end up defaulting on hundreds of billions of debt, but that won’t necessarily cause Eurozone GDP to decline; it’s already depressed because the money that was borrowed was spent unproductively. If anything, the painful restructuring that would inevitably follow in the wake of a default would likely result in higher living standards in the future. The world has survived large sovereign debt defaults many times in the past without disastrous economic consequences. Argentina's 2001 default on $132 billion comes to mind.

The disruption and fear that may be generated by bank failures could, however, disrupt growth insofar as investors become reluctant to accept risk and prefer instead to buy risk-free securities from governments like ours that have dubious uses for the money. Come to think of it, that has been happening a lot in recent years—Treasury has been borrowing trillions at extremely low interest rates from lenders seeking to minimize their risk, and spending the money in ways that are much less productive than if the money had been put to use by the private sector. The damage has been done, and it is reflected in disappointingly slow growth and relatively low valuation multiples.

In short, much of the disruption that can be expected from debt problems has already happened. Instead of fretting about defaults, the world should turn its attention to the aftermath of default, the new policies and adjustments that will be required, and the brighter prospects that these will entail for the future.

Does all this debt and its attendant problems mean the economic outlook is inescapably bleak? Will PIIGS defaults result in a collapse of the Eurozone banking system? Will debt default contagion bring about another global recession? Will debt defaults intensify lingering deflationary pressures? The short answer is that most of the bad effects of too much debt have already happened.

Debt has certainly become problematic, but the threat it poses to the world is likely being exaggerated. That’s because there are a number of popular misconceptions about debt, and because many ignore that the market has already factored in the likely consequences of defaults.

Debt is a zero-sum game, since one man’s debt is another man’s asset. Debt is an agreement between two parties to exchange cash now with a reversal of that exchange, plus interest, in the future. If the borrower fails to repay his debt (i.e., he defaults), then the borrower benefits by being relieved of some or all of his debt service obligations, and the lender suffers by not receiving some or all of his expected cash flows. Part of the interest the lender charges the borrower goes to offset the risk of default.

Debt payments by a borrower are not equivalent to flushing money down the toilet. The money borrower B pays to lender A is money that A will spend on something else. The amount of money available to the economy doesn’t change when debt is serviced or paid off. Demand doesn’t change, money simply changes hands. Similarly, the issuance of new debt does not create new demand. When A loans money to B, A must spend less in order for B to spend more.

Credit expansion is not the same as money creation. Central banks, not credit markets, control the amount of money in an economy. They typically do this by targeting the price of money (e.g., short-term interest rates), and that in turn increases or decreases banks’ ability to lend, and increased bank lending is what leads to new money creation. Credit expansion does not create any new money because the issuance of new debt only causes existing money to change hands.

Credit outstanding can grow faster than the amount of money in an economy without there being any inflationary consequences, because credit does not create new money or new demand; it simply redistributes existing money. Similarly, credit contraction can occur without there being any decline in overall output or any deflation, provided the central bank is properly overseeing the amount of money in the economy. Credit contraction, aka deleveraging, is a sign of increased money demand, which should be offset by an increased supply of money. The Federal Reserve has been doing exactly this with its quantitative easing program: responding to the private sector’s desire to reduce its debt burdens. That's why quantitative easing to date has not been inflationary.