A few days ago, Chairman Powell essentially admitted that the Fed will no longer be pursuing an aggressive tightening policy. Since then, key interest rates have registered some significant declines, and that is good news for the housing market, the economy in general, and the stock market. We have probably seen the end of the shortest and most dramatic round of Fed tightening in history.

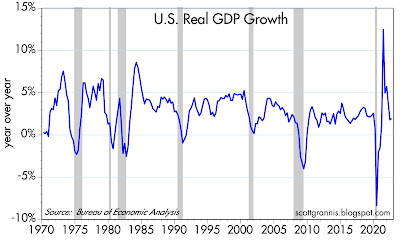

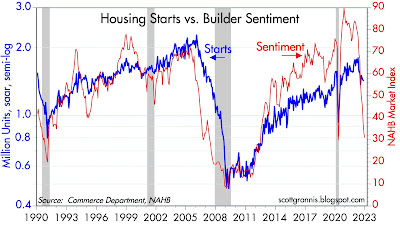

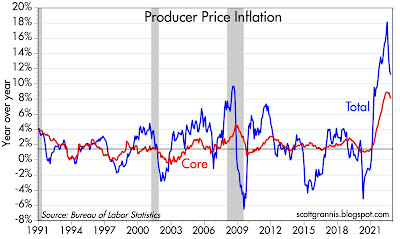

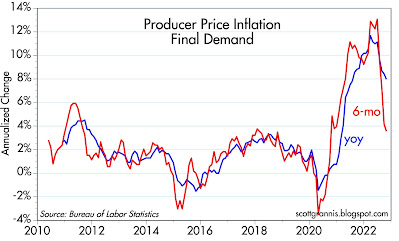

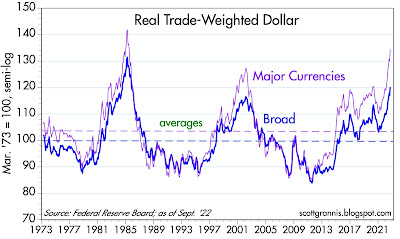

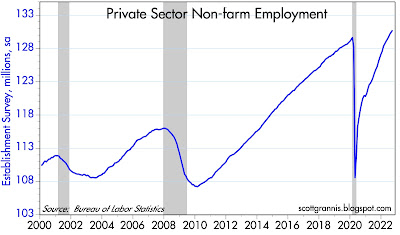

The Fed was late to see the inflation problem, which is very unfortunate, but they have not hesitated to act forcefully, and it seems to have worked. As almost always happens in the end stages of a Fed tightening, real yields have soared (up almost 400 bps in less than one year), the yield curve has inverted, the dollar has surged, commodity prices have dropped, the housing market has run into a brick wall, the stock market has sunk, and the economy appears set to enter a recession. All, of course, classic signs of very tight monetary conditions—tight enough to bring inflation down, and that is indeed what's happening.

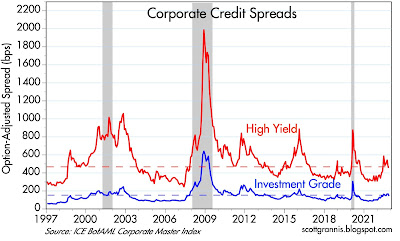

There are some unique features to this tightening cycle which bear attention. Most importantly, there is no liquidity shortage. Liquidity is the lifeblood of the bond and stock markets, because liquidity means that people can easily and quickly trade their positions and adjust their exposure to risk. We all know what happens when someone yells "Fire!" in a crowded theater: panic sets in and the exits quickly jam—casualties occur. But with plentiful liquidity, it's like being in a crowded open-air theater when someone yells fire—you simply walk outside unimpeded. And so it is today; there are few if any signs of the distress that typically accompanies very tight money. Credit spreads are low, especially the all-important swap spreads, which are a gauge of how easy it is for people to buy and sell all kinds of securities and risks in size (see Chart #1 in

this post for a history of swap spreads). Credit default spreads are low. Volatility is subsiding. There has been a surge of layoffs, but they are mostly concentrated in tech companies that had become seriously bloated. Unemployment claims are low and job growth has exceeded expectations; in fact, there are more job openings than there are people willing to work.

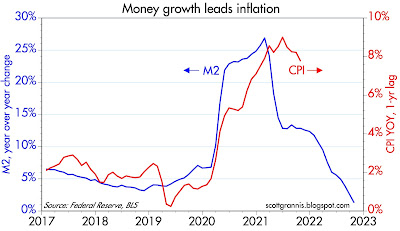

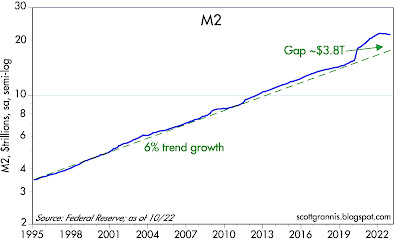

Another key difference this time around is that the bout of inflation we have suffered was not the result of Fed policy (it is usually is). It was the result of a massive surge in Covid "stimulus" payments which put trillions of dollars into the hands of people who were still hunkered down and unable to spend it. The result was a multi-trillion dollar surge in bank savings and deposit accounts. Once the Covid scare passed, the liquidity dam broke and a tsunami of price increases spread throughout the economy.

So it wasn't low interest rates that caused the problem, it was too much government spending. Higher interest rates came to the rescue, giving people and incentive to hold on to their extra cash, and that minimized the spending tsunami. Now, interest rates can decline and help the economy get back on a normal track fairly easily. It won't all happen at once, but the wheels have been set in motion. Meanwhile, M2 is declining, which means that excess cash is being reduced with the passage of time.

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of real yields on 5-yr TIPS. In the past year they have surged from -2% to almost +2%. That's an unprecedented swing of almost 400 bps in a relatively short time frame. That's why this year proved to be the most painful in history for anyone exposed to higher interest rates. Fortunately we appear to be waking up from this nightmare.

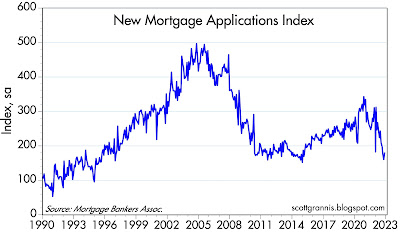

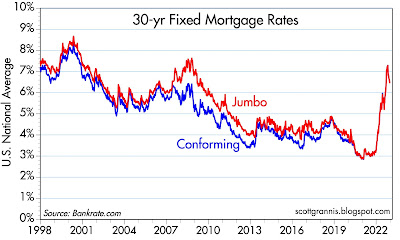

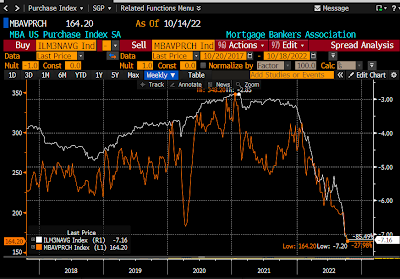

Chart #2 shows the national average rate on 30-yr fixed-rate mortgages. This has dropped from a high of 7.3% to now 6.5%: a decline of almost 80 bps in less than two months. This is the first step in making homes more affordable, but it won't be the last. Rates are going to have to decline significantly, and they should, even if 10-yr Treasury yields don't fall further. Chart #3 explains why.

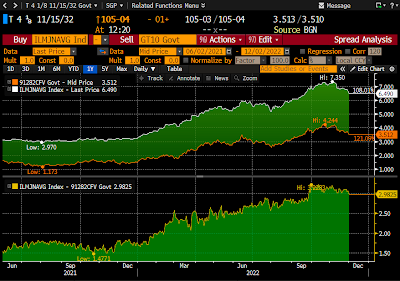

Chart #3 shows 30-yr mortgage rates (white line in the top half of the chart), 10-yr Treasury yields (orange line), and the spread between in the two in the bottom half of the chart. 10-yr Treasury yields are the benchmark for mortgage rates; mortgage rates typically run about 150 basis points above the 10-yr Treasury yield. In recent months, however, the spread ballooned to over 300 bps—twice the normal spread. If 10-yr Treasury yields stabilize around 3.5%, 30-yr mortgage rates should eventually decline to about 5%

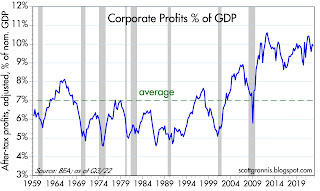

Chart #4 shows Credit Default Swap spreads, which reflect the market's assessment of the health of the economy and corporate profits. Spreads are still somewhat elevated, but they have declined impressively in the past few months. This is not what you would expect to see if the economy, as many seem to believe, were on the cusp of a recession.

While we're on the subject of market fears, it's timely to look at the burden of our surging

federal debt, which has now reached $24.6 trillion. You have probably seen many analysts saying it is $34.1 trillion, but that includes $6.9 trillion of intragovernmental holdings which is just an accounting fiction: money that one part of the government owes another. What counts is the debt that our government owes to the public.

$24.6 trillion is still an immense amount of debt. Relative to GDP, our national debt, now about 95% of GDP, was only once higher, at the tail end of World War II. Back then it got to almost 125% of GDP, but the world didn't end. In fact, after WWII, our debt/GDP ratio plunged as the economy boomed. It might seem improbable, but there is no a priori reason it can't happen again.

Chart #5

Furthermore, it is not inevitable that all this debt will push interest rates higher, thus imposing an impossible burden of debt service as many fear mongers are arguing. As Chart #5 shows, it would appear that a rising debt/GDP ratio can occur with lower interest rates, not higher. And a falling debt/GDP ratio can even correspond to higher interest rates.

Chart #6 shows the burden of our national debt, which is the cost of servicing the debt as a percentage of GDP. I've estimated what it will be by the end of this year. And as you can see, it will still be very low from an historical perspective because interest rates are still relatively low. If interest rates stabilize or decline from current levels, and the economy remains reasonably healthy, the debt burden is unlikely to reach unprecedented levels.

It all depends on how the economy behaves—how much inflation we have and how much growth. Higher inflation shrinks the burden of debt, because it can be paid back with cheaper dollars. A stronger economy boosts tax revenues, which helps support debt repayment. And in any event, paying back the debt is not equivalent to flushing money down the toilet. Every dollar of interest paid on our debt goes into someone's pocket. It doesn't disappear from the economy.

What's bad about our national debt is not the amount of debt that must be serviced, it's what was done with the money we borrowed. Therein lies the real burden of debt. If the money borrowed is squandered, then that places a huge burden on an economy that has not become more productive or more efficient. Unfortunately, a huge portion of our current debt (about $5-6 trillion) was money that was borrowed—or printed—and then handed out to the public. Using debt to finance spending is terrible, since it doesn't enhance the economy's productivity. We essentially wasted $5-6 trillion that might have been better spent on investments that create jobs. The real burden of that debt will thus be paid by future generations, in the form of a slower-than-average rise in living standards.