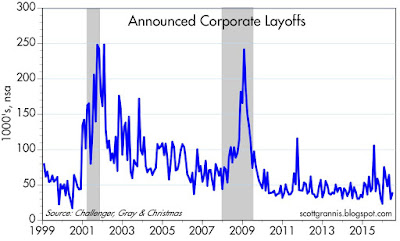

The data we can trust, however—tax receipts, market-based prices, corporate profits, unemployment claims—are in general agreement with the GDP stats, as I've been noting off and on for the past several months. The economy is most likely still growing at a sub-par pace of 2% or so, as it has on average since 2009 (see chart above). Just because it's growing slowly is no reason to worry that a recession is imminent. The analogy that says a slow-growing economy is like an airplane approaching stall speed is flawed. Indeed, recessions typically follow periods of excesses—soaring home prices, rising inflation, widespread optimism—rather than periods dominated by risk aversion such as we have today. Risk aversion can still be found in abundance: just look at the extremely low level of Treasury yields, and the lack of business investment despite strong corporate profits.

If Donald Trump wants to win the election, his campaign ought to promote the facts to be found in the chart above. The economy's ability to grow by a little more than 3% per year on average for over four decades suddenly vanished beginning in 2009. For the first time in post-war history, the economy failed to recover to its former growth path following the 2008-09 recession, and it has managed to grow only 2.1% since then. Seven years of slow growth following a big recession have left the economy about $3 trillion smaller than it could have been. We're missing out on approximately $3 trillion per year in income, and that's yuuge. Put another way, the average family could have been earning about 18% more this year if the economy had recovered in typical fashion, and of course there would have been many more people working. The $3 trillion GDP shortfall is the easiest way to understand the widespread level of discontent in the U.S. today.

As I noted some years ago, all the spending and borrowing that was supposed to "stimulate" the economy beginning in 2009 was essentially flushed down the toilet. Since 2009 we've conducted a laboratory experiment in the power of government spending and income redistribution to grow the economy by stimulating demand, and the result is proof that Keynesian theories are destructive, not stimulative. Neither government spending nor easy money has the power to create growth out of thin air, but politicians want to convince you that they do. The economy is weak today because we have wasted many trillions of dollars on transfer payments that only create perverse incentives to work less.

Hillary Clinton does not understand this, but Donald Trump most likely does. Clinton has vowed to "change" things for the better by raising taxes on the rich and profitable, and distributing the spoils to the middle class. But that is just a rehash of all that has gone wrong for the past seven years. Real change demands tax reform and simplification; lower and flatter marginal tax rates; a much lower corporate income tax; and extensive regulatory reform and relief. We've got to increase the after-tax incentives to work and take on risk, and reduce regulatory burdens (which add immeasurably to the cost of doing business), if we want a stronger economy. It's that simple. The reward to doing things right would be recapturing the $3 trillion annual shortfall in the economy's productive capacity. The upside potential lying dormant in today's economy is staggering. (And by the way, that's one big reason to remain optimistic.)

One of the best things about the past two decades is the strength of corporate profits, as illustrated in the chart above. From 1958 through the mid-90s after-tax corporate profits averaged about 5% of GDP (note that the right y-axis, corporate profits, is 5% of the left y-axis, nominal GDP). But while corporations have generated about $1.5 trillion in after-tax profits on average over the past seven years (about $10.5 trillion in total), federal government debt held by the public (i.e., net borrowing) has increased by about $6.8 trillion. That means that, in effect, our government has borrowed 2 out of every 3 dollars of corporate profits for the past seven years, and then handed the money out to favored constituencies. In return, the government has enjoyed the lowest borrowing costs in history, but the economy has squandered much of its scarce resources. We've plowed two-thirds of the profits of the most valuable companies in the world into (mostly) transfer payments that have generated zero net growth. This recovery has seen a colossal waste of money.

Another way to see this is to look at business investment, which has been miserable for many years. Businesses have been very profitable, but for whatever reason (e.g., the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world, which has discouraged businesses from repatriating trillions of dollars of overseas profits) they have been extraordinarily reluctant to reinvest those profits. Call it risk aversion, or as I've deemed it, the reluctant recovery.

Capital goods orders (see chart above) are a good proxy for business investment. Capital goods are the things that make labor more productive. You can't grow the economy without investing in tools and technology that make workers more productive. Lamentably, capital goods orders today are about the same as they were in the late 1990s. In real terms they have declined by 30%, even though the economy has grown by over one-third over the same period.

Private Fixed Investment tells the same story. Relative to GDP, fixed investment (structures, equipment, and software that are used in the production of goods and service) has declined by almost 20% since 2000. The go-go growth of the mid-80s and the late 90s were driven by strong investment. Today's weak investment climate has given us a miserably weak economy. It's not surprising.

What is surprising is that so few seem to understand that the solution to our weak growth is to do things that encourage investment, work, and risk-taking. That includes not only lower taxes and reduced regulatory burdens but also greater confidence that conditions will remain favorable in the future. How many today are willing to bet huge sums that taxes will be lower and flatter across the board a year or two or three from now? It's almost impossible to know at this point, with the election still a toss-up between one candidate who vows to increase taxes and regulatory burdens and the other who would likely reduce them.

I despise Donald Trump as a person (just as I despised Bill Clinton as a person), but I do think both Donald and Bill have a much better understanding of how business and the economy work than Hillary does. If Trump were able to push through a growth agenda, the rewards could more than make up for his failings in other areas. It remains a mystery why Hillary wants to double down on Obama's failed economic agenda when her husband's was so different and so much more successful.

To judge from the rhetoric, the election is all about personalities: Hillary is a corrupt liar, Trump is a xenophobic, redneck egomaniac. The list of negatives is long for each. Instead it should be all about which one would be best for the economy. On that score, Trump should win hands down.