Thursday, September 30, 2010

Oil is likely to remain somewhat expensive

Changing the subject, here's an updated version of an interesting chart I haven't shown for a long time. It compares the real price of crude oil with the total number of oil and gas drilling rigs operated worldwide (including offshore rigs). Not surprisingly, drilling activity responds to changes in the real price of crude with a lag. What stands out for the recent period is that while crude prices in real terms are back to the levels of the early 1980s, there are still far fewer rigs operating today than there were back then. Rig counts are still rising, however, so maybe the industry will eventually catch up. But the relatively low level of exploration activity today may help explain why crude prices are still quite high from an historical perspective. This further suggests that crude prices could remain in their current range of $70-80/bbl for quite some time.

This second chart is a reminder that the relatively high price of oil in real terms is much less burdensome for the economy today than it was in the early 1980s. That's because, thanks to conservation efforts and improved technology, the U.S. economy today uses about half as much oil per unit of output as it did in the early 1980s.

Caveat: I'm not an expert on the oil and gas market by any stretch; I'm just making some informed guesses based on a simple analysis of historical patterns.

The claims situation is slowly improving

Claims fell more than expected in the latest week, to a level (453K) that is a bit below the average for the year to date (465K). It's now clear that the unexpected swings in the index that occurred in July and August were the result of faulty seasonal factors (i.e., the actual numbers didn't behave as the seasonals had expected). The underlying trend in the labor market has been large unchanged this year, and that is a move towards very gradual improvement.

This chart shows the actual, unadjusted claims number, which has been clearly trending down all year. Importantly, it is now below the levels that prevailed at this time two years ago. Normally, actual claims would be moving higher at this time of the year, but so far that hasn't happened.

As this last chart shows, the biggest change in the claims situation has been the significant decline over the course of the year in the number of persons receiving unemployment insurance. That number has fallen by 3.75 million since the high at the beginning of this year. It's likely that at least some portion of this decline has occurred because some people are finding jobs. According to the household survey, some 1.8 million new private sector jobs were created in the first 8 months of this year. The improvements in claims to date suggests that next week's jobs number could hold some more pleasant surprises for the market.

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Thoughts on quantitative easing

Ever since the Aug 10th FOMC statement—in which the Fed announced it would be buying longer-term Treasury securities with the proceeds of its maturing or prepaid Agency and MBS holdings—there has been a very interesting and tight correlation between the slope of the Treasury yield curve from 10 to 30 years and the market's own inflation expectations. This is shown in the above chart, with the red line representing the 5-yr, 5-yr forward inflation expectations embedded in TIPS securities, and the blue line representing the slope of the Treasury yield curve from 10 to 30 years.

What stands out is that the slope of the longer end of the yield curve is now a good proxy for the market's inflation expectations. That is at it should be, of course, since the higher inflation expectations, the greater the premium that investors should demand to own 30-yr bonds instead of 10-yr bonds. But it hasn't been that way for some time. And as the next chart shows, the slope of the 2-10 portion of the yield curve has been trending down all year even as inflation expectations have perked up. Plus, the flattening of the 2-10 portion of the curve has occurred under very unusual circumstances. (Typically, the curve flattens when the Fed pushes up short-term rates, and it steepens when the Fed lowers rates. For some time now, the Fed has kept short-term rates steady at very low levels, while longer-term rates have been falling.)

So the behavior of the yield curve is telling us something important, namely that the Fed's purchases of (and intention to continue purchasing) longer-term Treasury notes is having an impact. The Fed is artificially depressing yields out to 10 years, and that's not surprising because that's what they are aiming for. The Fed believes that lower long-term yields will be stimulative for the economy.

Whether the Fed's purchases of bonds will prove to be a stimulus for the economy remains to be seen, of course. Since early August, lower 5-yr and 10-yr Treasury yields have not resulted in any significant decline in mortgage rates, for example, because the spread between Treasuries and mortgage rates has simply widened. This is not unusual at all, it is simply the market saying that it doesn't believe lower Treasury yields are permanent, and/or it doesn't think that buying mortgages at lower yields is likely to prove profitable. And even if the Fed were able to drive mortgage rates to artificially low levels, I think it's questionable at best whether this would prove to be a stimulus for the economy.

Artificially low borrowing costs are part of the reason we're in the mess we're in. Cheap credit, among other things, helped fuel the housing boom, which eventually went bust. Flooding the system with money could help bail out underwater homeowners by pushing up home prices, but only at the cost of another round of reflation (perhaps housing prices, or in some other area of the economy, who knows?). Plus, it's hard to convince people to borrow these days, when so many are still smarting from having borrowed too much some years ago.

But I suppose that if the Fed tried hard enough for long enough, it would soon become apparent to intelligent people that taking out a whopping big mortgage was a good way to become rich. Borrow now at a super-low fixed rate for 30 years, buy a bigger home or some other tangible asset, then sit back and wait for the price level to rise and reduce the cost of repaying your loan. If enough people decide to borrow more, that translates into a reduction in the demand for money, and that has the effect of increasing the amount of money in the system relative to the prices of goods and services. It shouldn't be hard to see how that would in turn result in a higher price level for just about everything. It won't, however, result in any material change in the economy's ability to grow, since growth only occurs when the productivity of labor rises—when we collectively produce more for a given amount of effort.

I think the bond market is already thinking along these lines, and that is why the long end of the yield curve is steepening. The Fed may be able to depress 10-yr yields by promising to keep the funds rate at zero for an extended period of time, but there is no way the Fed can convince investors to buy 30-yr bonds a ridiculously low yields. Savvy investors are figuring this out: quantitative easing is going to push up inflation, so the thing to do is to shun long-term bonds (or borrow at long-term rates), and buy tangible assets or other currencies. Did I mention that gold and other currencies are already rising? And that's why the steepening of the long end of the curve is indeed a good sign that quantitative easing is going to lift inflation.

Along the way to higher inflation—which could take years to show up—this Fed exercise in quantitative easing may have at least one salutary effect, and that will be to vanquish the widespread fears of deflation. Convincing people that holding onto cash yielding zero is a bad idea is one way of boosting the velocity of money, and that is in turn a way of boosting the economy, if only because velocity has been very depressed. People have been hoarding money since the financial crisis erupted, and the hoarding continues to this day. That has depressed growth in the economy, which is another way of saying that fear of the future and risk aversion are not compatible with healthy growth.

I'm not condoning a QE2, however. I am hopeful, in fact, that it will not prove necessary, and I think that will become obvious as more signs of economic growth show up in coming months.

Online job demand points to rising employment

This chart comes from The Conference Board, and it shows the relationship between the level of employment (red line) and an index of online help-wanted ads (blue line). Over the relatively short sample period available, ads seem to do a good job of leading employment, which in turn suggests that we should be seeing further job gains in the months ahead.

HT: Mark Perry, who notes that "the 4,296,100 job vacancies in September were the highest level since November 2008, almost two years ago." This is a fairly impressive and positive sign in my view.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Let's follow the lead of Sweden

Sweden? Yes, Sweden, where conservatives have demonstrated that supply-side theories do work as advertised: "when you tax something less, you get more of it." Read the whole story in "Swedish conservatives bucked the recession by lowering taxes." Some excerpts follow:

HT: Don Luskin

This week Fredrik Reinfeldt is celebrating the first re-election in history of his party, the Moderaterna. He is also celebrating the success of an extraordinary experiment. His response to the recession was to cut taxes, a move his critics said the country could not afford. The European Commission warned him it would end in tears. But instead, the lower taxes were a spur to growth and Sweden now has the fastest-growing economy in the Western world.

When elected four years ago, leading a four-party coalition, Reinfeldt had a striking slogan. 'We are the new workers' party,' he said, meaning he would cut taxes for those in employment, but not for those on benefits. When faced with protests about how the poorest would be paying a higher marginal tax rate, he appealed to voters' innate sense of fairness - and resentment at the high level of welfare dependency. At every stage, his ministers would explain the basics of low-tax economics. Cut tax on wages, and you increase the incentive to work. 'This will increase employment,' Reinfeldt said. 'Permanently.'

Tax on low-paid jobs fell sharpest. Nursing assistants, for example, saw their tax bill drop by a fifth. The aim was to make work compete more aggressively with Sweden's famously generous welfare state.

Like most of Europe, [in response to the recession] Sweden launched a stimulus, but Reinfeldt set aside two thirds of his for a tax cut. Corporation tax fell from 28 per cent to 26.3 per cent, taxes on jobs were cut further still while income tax thresholds were raised. Determined not to let a crisis go to waste, he declared the tax cuts permanent.

HT: Don Luskin

Tech and consumer stocks have recovered nicely

The world is so gloomy that I thought it would be nice to show some good news. As this chart shows, both tech sector and consumer sector stocks have almost fully recovered to their pre-recession highs. Consumer staples are only 5% below their late-2007 (and all-time) high, while tech stocks are less than 3% below their late-2007 high.

The tech sector is still well below its very-inflated 2000 high, but its recovery to date from the 2002 lows is extremely impressive. It just goes to show that this economy is quite dynamic, and able to bounce back from even the worst of news.

Confidence remains low, and that's good for investors

The September reading from this measure of confidence fell, and that spooked the market temporarily this mornign. In my view, this is old news, and it simply validates what I have been saying for a long time: the market is priced to very pessimistic assumptions. Optimism is hard to come by, and consumers especially are still quite concerned about what's going on in Washington and the lack of a meaningful recovery. But when the majority of people are very worried, that gives optimists some attractive odds to bet against the prevailing mood. If there is just a little bit of improvement going forward, this could be good for prices of risky assets. Investors should worry when confidence is high, as it was before every recession in the past.

The housing market has adjusted to new realities

The top chart shows inflation-adjusted prices for homes in 10 major metropolitan areas since 1987, while the bottom chart shows prices in 20 major metropolitan areas since 2000 (and is also seasonally-adjusted). Both show that real home prices have fallen by one-third since the peak in 2006, and both show that prices stopped falling over one year ago.

Because of the lags in the way this index is constructed, the latest datapoint (July) tells us only about the average of prices in the second quarter of this year, and that's admittedly old news. But it's impressive that prices have remained firm for over one year after a significant decline. This is the way you would expect an overbuilt market to work: prices have to decline to a new clearing level that allows excess inventory to be worked off. That has happened.

The issue going forward is whether we need another significant decline to allow what is presumed to be a "new wave" of foreclosures to be sold. Put me in the skeptical column, because a) the housing market has had almost 5 years to adjust to new realities, b) prices have adjusted very significantly, c) prices have been stable for over a year, d) mortgage rates have declined by one-third since their peak in 2006, which further reduces the effective cost of buying a home by a substantial amount, e) new home construction has plunged by two-thirds, which contributes mightily to work off the excess inventory of homes, and f) the economy has recovered and we are now seeing job and income gains. That adds up to a giant amount of price and inventory adjustment, and enough time for all sorts of things to be dealt with. Why would we need more?

The housing market is clearing and has apparently stabilized. It's time to worry about other things, such as what will happen to taxes beginning next year.

Monday, September 27, 2010

The market is priced to pessimistic assumptions

I haven't shown this chart for awhile, and in the meantime yields have fallen when I thought they would have risen. The colored "valuation zones" that I've added to the chart of 10-yr Treasury yields represent my guesstimate of the expectations/assumptions that underlie a given level of yield. Real investors determine the yield on 10-yr Treasuries, and they take into consideration a number of variables in coming to their decision to buy them. Chief among those is their outlook for economic growth and inflation, since those are the two variables that factor the most into the future course of the Fed funds rate. And the expected future course of the funds rate is ultimately the thing that most determines the level of the 10-yr Treasury yield. If the market expects growth to be very weak and inflation to be very low, the market will not expect the Fed to raise short-term interest rates for a long time. If the Fed stays on hold for many years, then a 10-yr Treasury yield of 2.5% looks very attractive relative to the expected return on staying in cash and earning almost nothing. That is the situation we find ourselves in today.

This is not to say, of course, that the market is always correct. I think one key to successful investing is identifying first what the market's assumptions are, and then deciding whether those assumptions could be wrong, and whether market pricing offers the investor attractive odds to "bet against" the market.

I knew that the market was expecting depression and deflation when yields fell to almost 2.0% at the end of 2009. That's because at the end of 2008, TIPS spreads were reflecting deflationary expectations, and corporate bond spreads were consistent with the assumption that as many as 50% of the companies in the U.S. would be out of business within the next several years. I had numerous posts in the fourth quarter of 2008 which expanded on the abysmal valuations and assumptions that were priced into the market at the time.

Today the market is revisiting the yield levels that we last saw near the end of 2008. There are some important differences this time around, however, which bear noting. For one, corporate credit spreads are an order of magnitude lower than they were in late 2008, which implies that the market currently is not expecting a depression, but rather something like a "double-dip" recession or a long period of agonizingly slow growth. Second, the implied volatility of equity and T-bond options is not nearly as high today as it was in late 2008, which suggests that the level of fear, doubt and uncertainty is much less. In a sense, the market seems more sure today that the economy will be very weak for a long time, whereas back then the market was terrified that we were headed over the edge of an abyss.

In my view, this means that the odds the market is offering to bet against it are not nearly as attractive today as they were in late 2008. Back then, you could make a fortune just betting that we weren't headed for the end of the world as we know it. Today, you need some amount of growth (which I'm guessing is 1-2% per year) and some positive inflation in order to make money.

Still, it seems to me that 10-yr Treasury yields are very low relative to the outlook implied by credit spreads and implied volatility. There is a disconnect, in other words, between Treasury yields and other key indicators of market valuation. Whether this makes Treasuries a bubble or not, I'm not sure. All I know is that if the economy grows 2% or more and inflation picks up just a little, it's not clear to me that the Fed will remain on hold indefinitely. That would challenge the market's current assumptions, and at the very least some holders of 10-yr Treasuries would likely get nervous and sell.

In order to like the idea of holding 10-yr Treasuries in your portfolio, in other words, you need to be quite sure that the economy is going nowhere for a long time, and that there are some lingering deflationary pressures out there which haven't been addressed by the Fed's $1 trillion injection of reserves into the banking system, or by the dollar's pervasive weakness against other currencies, commodity prices, and gold.

In short, the market is priced to some fairly pessimistic assumptions. I'm by nature an optimist, believing that free markets are a breeding ground for industrious people and new ideas that in turn lead to productivity gains and continually rising living standards. I'm also very encouraged by the sea change in the mood of the electorate—as reflected best in the astonishing appearance and rise of the Tea Party—and what this means for the future course of fiscal policy. Washington has been doing just about everything wrong for the past several years, and now there is reason to think that policy may get back on a more sensible and growth-generating track.

The deleveraging fallacy

Paul Krugman speaks for the bears when he argues that "when everyone tries to pay down debt at the same time, the result is a depressed economy and falling inflation, which cause the ratio of debt to income to rise if anything." I think his logic is flawed, just as the logic is flawed behind the assumption that an increase in outstanding debt leads to an increase in total demand.

The fallacy here is that borrowing increases demand, while deleveraging reduces demand. It's simply not true, except in the case that the lender happens to be a bank that is using its reserves to increase the money supply. Even then, an increase in the money supply cannot result in a real increase in demand, otherwise we could print our way to prosperity. Dumping money into the economy only increases prices.

If A borrows $100 from B and spends the money, there has been no increase in demand because B now has less money to spend. Similarly, if A repays his $100 loan to B, then A has less money to spend and B has more. When the private sector creates credit, it is not creating new money or new demand, it is only shifting money from one pocket to another. Now it's true that increased credit may result in a more efficient economy (though not necessarily), and that may result in a net increase in demand, but on the margin when one person lends to another, demand is shifted from one person to another, but no additional demand is created.

As supply-side theory tells us, new demand is created by new supply. Global demand cannot increase at all unless global production rises. Otherwise we could all get rich just by spending more, or as the late Jude Wanniski was fond of saying, "we could spend our way to prosperity." It just can't happen.

So deleveraging needn't result in a weak or depressed economy.

Mark Perry has a nice post today that is effectively a corollary to the above, recalling Milton Friedman's point that deficit spending is also powerless to stimulate an economy.

The fallacy here is that borrowing increases demand, while deleveraging reduces demand. It's simply not true, except in the case that the lender happens to be a bank that is using its reserves to increase the money supply. Even then, an increase in the money supply cannot result in a real increase in demand, otherwise we could print our way to prosperity. Dumping money into the economy only increases prices.

If A borrows $100 from B and spends the money, there has been no increase in demand because B now has less money to spend. Similarly, if A repays his $100 loan to B, then A has less money to spend and B has more. When the private sector creates credit, it is not creating new money or new demand, it is only shifting money from one pocket to another. Now it's true that increased credit may result in a more efficient economy (though not necessarily), and that may result in a net increase in demand, but on the margin when one person lends to another, demand is shifted from one person to another, but no additional demand is created.

As supply-side theory tells us, new demand is created by new supply. Global demand cannot increase at all unless global production rises. Otherwise we could all get rich just by spending more, or as the late Jude Wanniski was fond of saying, "we could spend our way to prosperity." It just can't happen.

So deleveraging needn't result in a weak or depressed economy.

Mark Perry has a nice post today that is effectively a corollary to the above, recalling Milton Friedman's point that deficit spending is also powerless to stimulate an economy.

Household financial obligations have eased considerably

According to a recent release by the Fed, households' financial burdens continued to decline in the second quarter of this year. From their peak in Q3/07, total household financial obligations as a % of disposable income have declined by fully 10%. And as this chart shows, debt and financial burdens today are about where they have been for the past 25 years on average.

Pessimists will argue that bankruptcy and foreclosure have been the drivers of reduced financial burdens, but while that may be true for a portion of the population, I think it is also the case that many people have been working hard to pay down debt in the past several years, while at the same time disposable personal income has been rising. In that regard, I note that disposable income (the denominator of the ratios in the chart) has increased on average about 3% per year per capita, and 4% per year in nominal terms, over the past 5 years. Thus, it's likely that most folks have seen their disposable income rise by more than their debt and financial obligations in recent years.

It's hard to see how this chart could be construed in a negative way. At the very least, we can say that consumers today are no more at risk from too much debt than they have been for the past several decades.

Pessimists will argue that bankruptcy and foreclosure have been the drivers of reduced financial burdens, but while that may be true for a portion of the population, I think it is also the case that many people have been working hard to pay down debt in the past several years, while at the same time disposable personal income has been rising. In that regard, I note that disposable income (the denominator of the ratios in the chart) has increased on average about 3% per year per capita, and 4% per year in nominal terms, over the past 5 years. Thus, it's likely that most folks have seen their disposable income rise by more than their debt and financial obligations in recent years.

It's hard to see how this chart could be construed in a negative way. At the very least, we can say that consumers today are no more at risk from too much debt than they have been for the past several decades.

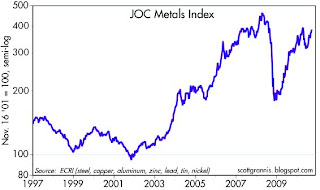

Commodities reach new all-time highs

It's official: the CRB Spot Commodities Index today reached a new all-time high (485), eclipsing the previous high (481) set in July 2008. This can be interpreted in many ways, of course, but let me state the obvious: this is not a symptom of deflation, and this is not a precursor of a double-dip recession. This is unambiguously symptomatic of growth and accommodative monetary policy.

What is amazing to me is that the Fed and so many commentators persist in wringing their hands over the possibility of deflation and a weakening of economic growth when commodity prices continue to move to all-time highs almost every day. I have yet to see anyone come up with a coherent explanation as to how we can be on the verge of deflation and recession when commodity prices are making new highs almost daily.

Commodity prices are measured in virtual real-time. They lie at the intersection of supply and demand across markets around the world. They tell us at the very least that economic activity is not contracting, it is expanding; that the price level is not declining, it is more likely increasing. Commodity prices are not subject to faulty seasonal adjustments, and they are not subject to revision. They are the here and now, and they are booming. And they are being led by gold, which is also at new all-time nominal highs.

Friday, September 24, 2010

Commodity recap

When so many commodities (the majority of which do not have futures contracts tied to them) rise by so much over the same period, I think it is logical to assume there is a common denominator or two at work behind the scenes. The prime suspects would be a) accommodative monetary policy and b) global growth. And the implications for investors is also straightforward: there is no reason to worry about a double-dip recession or deflation.

Stocks reconnect to corporate bonds

One month ago I noted the puzzling disconnect between equity prices and junk bond prices. They had been joined at the hip for a long time, but equities had drifted down while junk bond prices had drifted higher. I speculated that the corporate bond market was the one to follow in this case, since it has led the equity market many times in the past. I'm happy to report that this looks to have been a good call, with equities up almost 10% in the past month, and high-yield bond prices (using HYG as a proxy) up a bit less than 2%.

HT: Stephen Cook, for bringing this to my attention.

Capex continues very strong

Capital goods orders rose 4.1% in August, and July orders were revised up almost 3%, thus snuffing out any concerns that arose last month about a possible double-dip. Over the past six months orders are up at a very strong 23% annualized pace. This is undeniably good news, since it means that businesses are confident enough in the future to be investing in new plant and equipment, the seedcorn of new jobs and future productivity gains.

Update: I had some trouble getting this chart to show up correctly, but I think it works now. I'm also now more convinced that this series suffers from some faulty seasonal adjustment, since the first month of every quarter is always strong. So I'm going to stick with a 3-mo. moving average which gets rid of that problem. In any event, the 6-mo. annualized growth in capex is over 20% no matter how you measure it.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

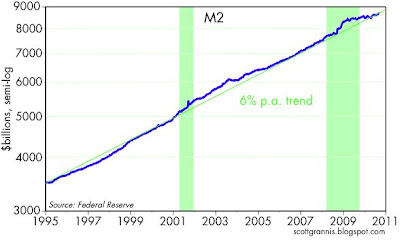

No shortage of money

Ever since late 2008 I have been making the point that whatever is wrong with the economy, it's not a shortage of money that is problem. That remains the case today. There are no signs that money is in short supply, either nominally or relative to the demand for money. Therefore there is no reason to worry about deflation or a deflation-induced slump in demand.

The best measure of money is M2, because it's definition hasn't changed much over time and for decades it has had a relatively stable relationship to GDP. I think most economists would agree on this. The first chart above shows the level of M2 over the past 16 years. As should be evident, M2 has grown on average about 6% a year. Sometimes faster, sometimes slower, but it always seems to revert to something like 6% a year, which also happens to be very close to the annualized growth rate of nominal GDP over the past 20 years or so. The slower growth of M2 in the past year or so is simply "payback" for very rapid growth in 2008, when a surge in money demand pushed up all monetary aggregates.

It was therefore not a coincidence that the the peak in M2 growth coincided almost exactly with the bottom of the stock market (March 2009). That was a big turning point, because what occurred was a rise in confidence accompanied by a decline in the demand for money. Money velocity picked up as people started spending the money they had hoarded, and that process continues to this day.

Meanwhile, the Fed force-fed $1 trillion to the banking system, swelling the monetary base and bank reserves by an unimaginable amount. Most of the extra reserves are still sitting idle at the Fed, though, since the world's demand for dollars remains elevated. (When demand for money is high, the demand for loans is weak. That's another way of saying that the world is still trying to deleverage, so demand for bank loans is not very strong.)

The recent increase in the M2 growth rate (M2 is up at 4.6% annualized rate in the past three months reflects a bit of an increase in money demand over that period, and that is likely a reflection of the confidence shock that resulted from concerns over the possible collapse of the european banking system. It is also the case that renewed concern over the health of the economy helped drive yields lower, and that in turn resulted in a surge of refinancing activity, which in turn has a strong tendency to increase money in circulation temporarily.

In short, I see nothing in the money numbers that is strange or foreboding—except, of course for the massive amount of bank reserves that lie in waiting to accommodate renewed loan demand. They haven't presented a problem so far, but at some point they could result in a significant expansion of bank lending which in turn could feed the fires of inflation if the Fed doesn't react in a timely fashion to drain those reserves. That's been a big worry for a long time, but so far nothing untoward has happened.

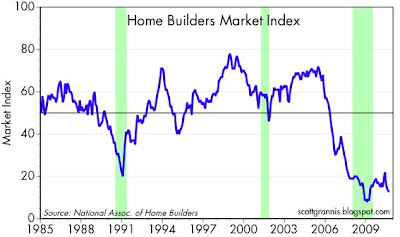

Housing market remains weak

The National Association of Realtors reported today that existing home sales rose only marginally in August, leaving them at very depressed levels (third chart above). The National Association of Homebuilders' survey of market conditions was flat in August (first chart above) and remains at depressed levels. About the only thing positive to be gained from current news on housing is that the inventory of homes for sale (second chart above) has been relatively flat for the past year or so. This, despite the expected flood of foreclosed homes coming on the market. All of this is consistent with the relatively depressed levels of new applications for home mortgages, and with the very low level of mortgage interest rates.

Housing is still very weak. Residential construction has fallen to 2.5% of GDP, it's lowest level in recorded history. This is not new news—it's been making headlines for many months. Are conditions deteriorating even further? That is possible, judging from the drop in existing home sales in recent months. But the recent decline in sales may also be payback for the burst of sales late last year and earlier this year, both of which were propelled in large part by government subsidy programs. If that's the case, then the recent weakness is just an unintended consequence of government meddling in the markets. That's not surprising.

Whatever the case, housing is not contributing to the economy's strength. Growth has to come from other sectors, and without a housing rebound it's going to be tough to post impressive growth numbers for at least the next year. But we've known that for some time—this is not new news.

Are other sectors of the economy growing? Absolutely, yes. Industrial production is up significantly. Exports are up significantly. Tax collections are up (meaning incomes and profits are up). Commodity prices are rising across the board. Private sector jobs are up 1.8 million so far this year, according to the household survey of employment. Default rates are way down (suggesting much stronger than expected cash flows for most businesses). On balance, the weight of evidence continues to point to growth, albeit growth that is still quite short of the levels which we should be seeing if this were a normal recovery. The economy is fighting the headwinds of a massive expansion of government spending and regulations, and all the uncertainty surrounding a rapid buildup of debt. The future course and strength of these headwinds will be decided within the next few months by the electorate. I think the electorate is going to vote overwhelmingly for Change, and the change will be a positive for the economy.

Weekly claims have been flat this year

As the top chart shows, weekly unemployment claims—abstracting from two periods in which seasonal adjustment factors proved faulty—have been essentially flat all year, averaging 465K, which also happens to be the latest weekly reading. No message here; this is entirely consistent with the sub-par recovery we've had so far.

As the second chart shows, however, the number of persons receiving unemployment compensation insurance is once again declining. In fact, the number has dropped by 1 million since the beginning of August. This could mean that more people are finding jobs, or it could mean that more people are sitting at home discouraged, or probably some of both. I think it's more of the former, and I note (again) in that regard that the household survey of private sector employment has recorded 1.8 million new jobs this year through August.

All this adds up to moderately positive news, consistent with a sub-par recovery. And again, not even a hint of a double-dip recession.

Leading indicators still point to growth

The Leading Indicators index rose a bit more than expected, and as the chart shows, the year over year change remains quite positive—a good indication that the economy is still growing. There is nothing in this series that would even suggest that the economy is slowing enough to qualify as the "double dip" recession that remains an obsession with so many observers. Instead, the index is behaving exactly at it has coming out of every recession in the past. It's natural for the growth in the index to slow as the economy continues to expand.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Commercial mortgage-backed securities are doing very well

This is a chart (source here) of the price of a AAA-rated basket of commercial mortgage-backed securities, most of which were originated in the heydays of 2007. Issued at par, this issue (which was assumed by almost everyone to be bullet-proof because of its AAA rating) fell to an unbelievable low of 55, but it has now rallied back to 92.7. You can check the prices of other AAA- and AA-rated securities issued earlier, and the story is basically the same—there has been a stunning recovery.

What this means is that in the depths of the depression and deflation fears, the market was priced to the expectation that almost half of the mortgages backing this security would default (or more likely, that 70% of the securities would default with a recovery value of 35%). It's not necessarily the case that the market was actually expecting a catastrophic default rate, but more likely, that the market's liquidity had evaporated at a time when many banks, and institutional investors were forced to sell at the height of the financial panic. Prices collapsed since lots of people wanted/needed to sell, and there were precious few buyers willing to buy.

Those institutions that decided to hold the securities were forced to write them down—with the losses going straight to their bottom line—because they were considered to be "impaired" according to accounting rules. But now the securities have almost doubled in value, yet the value recovered has in most cases not been recognized. This means there are lots of unrecognized profits on the books of institutional investors who were brave enough to hold these securities when everyone thought the sky was falling. I assume this is also good news for a lot of banks. And it's a vivid example of how illiquid and/or panicked markets can price securities to extremely unreasonable and even absurd assumptions. Markets are not perfect, and they can make huge mistakes. For an in-depth explanation of how this worked, I should once again recommend the book "Panic

In a similar vein, high-yield securities at the end of 2008 were priced to the expectation that an incredibly large percentage (as much as 50%) of companies would default on their obligations over the following 3-5 years. Yet we learn today that the default rate for high-yield securities will be less than 3% by the end of this year, according to Moody's.

Again, markets can and do make huge mistakes, especially when emotions are running high.

And, as should be obvious, conditions today are not nearly as bad as most people thought they would be.

Lowest 30-yr fixed mortgage rates in history

Thanks to 2.5% yields on 10-yr Treasuries and the ongoing improvement in the efficiency and liquidity of the mortgage-backed securities market (which has resulted in a tightening of the spread between conforming and jumbo rates), homebuyers today can take advantage of the lowest 30-yr fixed-rate mortgages in history, whether for a conforming or a jumbo loan.

One reason rates are so low is that demand for mortgage loans is also relatively low, as reflected in the above chart, which shows a measure of all mortgage applications for the purchase of a single-family home. The volume of new mortgage applications has fallen significantly since the peak of the housing market in 2005, but I note that the current volume is still higher than pre-1997 levels. Things have really cooled off, but they haven't ground to a halt by any means.

The other reason for low rates is that demand for high-quality yield is very strong. Investors are willing to accept 2.5% yields on 10-yr Treasuries and 3.4% yields on MBS because they worry about the ability of alternative investments to do better on a risk-adjusted basis. As I've noted before, the last time yields were this low for any meaningful period of time was in the late 1930s and 40s, when investing attitudes were powerfully shaped by depression and deflation.

Looking at both sides of the mortgage equation thus reveals great fear and uncertainty about the future: homebuyers worried that prices might fall further, and investors worried that the entire economy is at risk of a double-dip. That's one more reason to believe there is a lot of bad news that has been priced into today's market. This affords the investor an excellent cushion, since the mere absence of bad news ends up being a positive for prices.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Fed policy restarts the reflation trade

The FOMC's announcement today didn't reveal any signs of panic on the part of the Fed, but it did further open the door to another round of quantitative easing (aka QE2): "... the committee is prepared to provide additional accommodation if needed to support the economic recovery and to return inflation, over time, to levels consistent with its mandate." The market rationally interpreted this to be yet another sign that the Fed would rather err on the side of more inflation rather than less (or deflation). Predictably, measures of inflation expectations rose across the board. Gold has risen some $37/oz. so far this month, reaching yet another all-time high today. Gold is up against almost all currencies this month, but more so against the dollar, since it has fallen about 1.2% against a basket of major currencies.

TIPS are a reliable, if conservative, hedge against inflation, and TIPS yields/prices reached a new all-time low/high today. This is a direct reflection of investors' demands for inflation hedges, just as are record-high gold prices. Real yields on 10-yr TIPS have fallen 20 bps so far this month, while yields on 10-yr Treasuries are up 10 bps on the month; this translates into a 30 bps increase in average annual CPI expectations over the next 10 years. A more sensitive measure of inflation expectations, which is preferred by the Fed, is the 5-yr, 5-yr forward breakeven inflation rate; it has risen by over 50 bps so far this month, to a current 2.54%.

Other sectors of the bond market also reveal a recent increase in inflation expectations. As the chart above shows, the spread between 10- and 30-yr Treasury bond yields is now about as high as it has ever been (on a daily basis, we saw a record-high spread of 124 bps in early August). By insisting that short-term rates will remain low for a long time come what may, the Fed has helped 10-yr yields fall. But investors in 30-yr bonds have little or no reason to worry about what the funds rate will average over the next 10 years (a factor that does weigh heavily on the decision whether or not to buy the 10-yr), and they have decided that inflation risk outweighs carry concerns; as a result, 30-yr yields are up 25 bps on the month while 10-yr yields are up only 10 bps.

So we have now reached the point where the Fed's actions and its talk are definitely boosting reflationary expectations. By the same token, deflationary fears are declining. Monetary policy is "gaining traction," as economists are wont to say. Much as I hate the thought of higher inflation, I am not surprised to see equity prices up almost 9% so far this month. Reflation is good news for the equity market (and for high yield bonds) because a) it perforce reduces deflation risk, and b) it increases expected future cash flows without (so far) causing any significant rise in long-term interest rates.

My sense is that with the economy still on the mend—albeit slowly (i.e., modest growth of 3-4%, enough to bring down the unemployment rate in a very slow and painful fashion), and reflationary monetary policy gaining traction, we are now seeing a virtuous cycle kicking in that will at the very least act to help the economy grow. Consumers and businesses that have been hoarding massive amounts of money (as reflected in 12% decline in the velocity of M2 since the end of 2007) are now feeling increased pressures to unhoard some of that money, releasing it to be spent in a fashion that boosts nominal and real GDP. In the latter stages of this reflation process we would likely see an obvious buildup of inflation pressures, but for now this is of secondary concern.

Market expectations are dismal

As we wait for the Fed to tell us that not much has changed and they expect to keep rates low for a long time, I thought it would be interesting to show what market expectations are for future Fed actions. This chart shows the expected Fed funds rate one year in the future (using the one-year forward futures contract on Fed funds). Today the expected rate for Sep. '11 is 0.3%, which means that the market is not really expecting any chance of a tightening in monetary policy for the next year.

To my mind, this is characteristic of a market that has very little hope for an economic recovery, and very little concern about rising inflation. It is also the least optimistic view of the future that we have seen since before the recent recession started. This market is braced for bad news. In the absence of bad news, risky asset prices would likely rally.

UPDATE: With the FOMC's statement suggesting that the Fed continues to believe that the economy is on a slow path to recovery (i.e., the Fed is not panicking), equity prices have rallied.

Residential construction still in a bottoming formation

August housing starts came in a bit higher than expected, and remain consistent with a view that residential construction bottomed in the second quarter of last year, but has since made little progress. (Housing starts are the green line in the above chart.) Always on the lookout for market-based indicators that may lead the numbers put out by government agencies, I note that the Bloomberg index of 17 major homebuilder stocks (red line in the above chart) may fit the bill. It bottomed in the first quarter of last year and has spent about 18 months consolidating. It also predicted the modest slump in housing starts in May-July, and the modest upturn in August. Millions of investors on the ground and crunching numbers may prove better at divining the course of the housing industry than the folks at the U.S. Census Bureau who put out the housing starts number each month.

At the very least, I would venture to say that with housing starts and homebuilders' stocks failing to reach new lows after hitting bottom well over a year ago, one can say with some degree of confidence that we have seen the worst of the housing recession. More and more the issue becomes the timing and the strength of the recovery.

UPDATE: Here is a long-term chart of housing starts. Note how the past two years have seen the most severe drop in residential construction in recorded history, and the weakness has persisted far longer than in any prior recession. The good news is that once the excess inventory of homes is depleted, the rebound in construction—which does not appear imminent, but should be starting within the next 6-9 months—should be fairly dramatic.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Commodities: onward and upward

Commodities continue to rise, with gold making new highs again today, and non-energy industrial commodity prices (as measured by the CRB Spot Index) having essentially completely reversed their 2008 plunge. I've been highlighting rising commodity prices for well over a year as a good indicator of improving global economic health (most recent post here) and as a good indicator of the fact that monetary policy around the world is accommodative and therefore the risk of deflation is practically nil. Rising commodity prices are thus a good antidote to the doom, gloom, and deflation concerns that seem to be holding back so many investors who are content to leave significant sums in zero-interest-rate cash.

Before I proceed, this may be an opportune time to respond to a reader's request that I clarify the difference between contraction and deflation. A contraction refers to a shrinkage in the volume of economic activity, whereas deflation refers to a general decline in most if not all prices. These two conditions need not occur simultaneously, contrary to popular belief. In fact, it is quite possible for an economy to shrink even as prices rise; you have only to look at Argentina during its flirtation with hyperinflation in the 1970s and 80s to see this combination in action. This has relevance to the current situation in the U.S., since it seems that a great number of people are concerned that the dismal performance of, and the substantial "slack" that exists in the U.S. economy (all of which are summed up in the phrase "weak demand"), combine to almost ensure the onset of deflation. Deflation, in turn, is presumed to lead to a self-perpetuating economic slump, eventually ending in depression and deflation. What the deflationists ignore is the ongoing and impressive rise in gold and commodity prices, the 8 1/2 year slump in the value of the dollar (which means that most prices outside the U.S. have risen relative to our prices), the 2.5% annual inflation expectations embedded in TIPS prices, the negative real Fed funds rate, and the unusually steep Treasury yield curve, all of which argue strongly against deflation.

Instead, the deflationists believe that weak demand currently and prospectively will lead to falling prices. Weak housing demand has certainly led to falling housing prices, but weak demand shows up nowhere in the commodity markets. Some sectors of the U.S. and global economies are weak, and that weakness is reflected in falling prices, but that is not a statement that can be generalized. Some prices are falling, but lots of prices are rising, and since there is no evidence that money is in short supply, we have no reason to expect that all prices will fall in the future. Deflation, after all, happens only when there is a shortage of money relative to the demand for it, just as inflation happens when there is a surplus of money relative to the demand for it.

Deflationists also misunderstand the behavior of inflation following recessions. It is true that inflation almost always declines in the wake of recessions. But that's not because weak demand pulls prices down. It's because almost all recessions have been caused by very tight monetary policy. Very tight monetary policy—easily seen in the form of an inverted yield curve and a very high real Fed funds rate—first acts to disturb economic activity, then acts to bring inflation down. The lags are long and variable, of course, but today the Fed is more accommodative than ever before, and that is the biggest reason to ignore deflation risk.

Before worrying about deflation or even a decline in commodity prices, we would need to see at the very least some steps taken by the Federal Reserve to rein in the supply of dollars—either by withdrawing reserves from the banking system, or by raising interest rates and substantially flattening or inverting the yield curve. We would also need to see those moves result in a strengthening of the dollar relative to other currencies and relative to gold. I'm not holding my breath for any of these events to happen, and that's unfortunate since it means there is a lot of inflation uncertainty out there that makes it difficult for investors to have confidence in the future.

I am not saying that a lot of inflation is good for an economy or for the equity market. But right now the issue is not whether we have a lot of inflation or not; the issue is whether we have deflation or not. Once the market has overcome its fear of deflation, then it will be time to worry about how high inflation is likely to rise. For now, rising commodity prices are a direct reflection of declining deflationary and recessionary risks, and that is one of the factors driving the equity market higher.

Before I proceed, this may be an opportune time to respond to a reader's request that I clarify the difference between contraction and deflation. A contraction refers to a shrinkage in the volume of economic activity, whereas deflation refers to a general decline in most if not all prices. These two conditions need not occur simultaneously, contrary to popular belief. In fact, it is quite possible for an economy to shrink even as prices rise; you have only to look at Argentina during its flirtation with hyperinflation in the 1970s and 80s to see this combination in action. This has relevance to the current situation in the U.S., since it seems that a great number of people are concerned that the dismal performance of, and the substantial "slack" that exists in the U.S. economy (all of which are summed up in the phrase "weak demand"), combine to almost ensure the onset of deflation. Deflation, in turn, is presumed to lead to a self-perpetuating economic slump, eventually ending in depression and deflation. What the deflationists ignore is the ongoing and impressive rise in gold and commodity prices, the 8 1/2 year slump in the value of the dollar (which means that most prices outside the U.S. have risen relative to our prices), the 2.5% annual inflation expectations embedded in TIPS prices, the negative real Fed funds rate, and the unusually steep Treasury yield curve, all of which argue strongly against deflation.

Instead, the deflationists believe that weak demand currently and prospectively will lead to falling prices. Weak housing demand has certainly led to falling housing prices, but weak demand shows up nowhere in the commodity markets. Some sectors of the U.S. and global economies are weak, and that weakness is reflected in falling prices, but that is not a statement that can be generalized. Some prices are falling, but lots of prices are rising, and since there is no evidence that money is in short supply, we have no reason to expect that all prices will fall in the future. Deflation, after all, happens only when there is a shortage of money relative to the demand for it, just as inflation happens when there is a surplus of money relative to the demand for it.

Deflationists also misunderstand the behavior of inflation following recessions. It is true that inflation almost always declines in the wake of recessions. But that's not because weak demand pulls prices down. It's because almost all recessions have been caused by very tight monetary policy. Very tight monetary policy—easily seen in the form of an inverted yield curve and a very high real Fed funds rate—first acts to disturb economic activity, then acts to bring inflation down. The lags are long and variable, of course, but today the Fed is more accommodative than ever before, and that is the biggest reason to ignore deflation risk.

Before worrying about deflation or even a decline in commodity prices, we would need to see at the very least some steps taken by the Federal Reserve to rein in the supply of dollars—either by withdrawing reserves from the banking system, or by raising interest rates and substantially flattening or inverting the yield curve. We would also need to see those moves result in a strengthening of the dollar relative to other currencies and relative to gold. I'm not holding my breath for any of these events to happen, and that's unfortunate since it means there is a lot of inflation uncertainty out there that makes it difficult for investors to have confidence in the future.

I am not saying that a lot of inflation is good for an economy or for the equity market. But right now the issue is not whether we have a lot of inflation or not; the issue is whether we have deflation or not. Once the market has overcome its fear of deflation, then it will be time to worry about how high inflation is likely to rise. For now, rising commodity prices are a direct reflection of declining deflationary and recessionary risks, and that is one of the factors driving the equity market higher.

November's Choice: Free markets or managed capitalism

Somehow I missed this article by Arthur Brooks and Paul Ryan in last week's WSJ: "The Size of Government and the Choice This Fall." As a devoted fan of free markets and a believer in limited government, I think the article deserves some special mention, especially since it is quite good and in the best tradition of the Tea Party, of which I am also quite fond. Here are some excerpts, but read the whole thing if you haven't.

I share the authors' optimism, and their belief that voters will make the right choice in November. This is one of the major reasons I have remained optimistic since late 2008, despite the onslaught of Big Government. Too much government spending, too much income redistribution, and too much oppressive regulation have been major headwinds to economic recovery. With any luck this sea-change in the mood of the electorate that has been brewing since April 2009 will be able to reverse our statist course and eventually restore the economy to health.

And did I mention that I like the idea of Paul Ryan for President in 2012?

HT: Russell Redenbaugh

As we move into this election season, Americans are being asked to choose between candidates and political parties. But the true decision we will be making is this: Do we still want our traditional American free enterprise system, or do we prefer a European-style social democracy? This is a choice between free markets and managed capitalism; between limited government and an ever-expanding state; between rewarding entrepreneurs and equalizing economic rewards.

We [must] decide which ideal we prefer: a free enterprise society with a solid but limited safety net, or a cradle-to-grave, redistributive welfare state. Most Americans believe in assisting those temporarily down on their luck and those who cannot help themselves, as well as a public-private system of pensions for a secure retirement. But a clear majority believes that income redistribution and government care should be the exception and not the rule.

Unfortunately, many political leaders from both parties in recent years have purposively obscured the fundamental choice we must make by focusing on individual spending issues and programs while ignoring the big picture of America's free enterprise culture. In this way, redistribution and statism always win out over limited government and private markets.

Individually, these things might sound fine. Multiply them and add them all up, though, and you have a system that most Americans manifestly oppose—one that creates a crushing burden of debt and teaches our children and grandchildren that government is the solution to all our problems.

More and more Americans are catching on to the scam. Every day, more see that the road to serfdom in America does not involve a knock in the night or a jack-booted thug. It starts with smooth-talking politicians offering seemingly innocuous compromises, and an opportunistic leadership that chooses not to stand up for America's enduring principles of freedom and entrepreneurship.

As this reality dawns, and the implications become clear to millions of Americans, we believe we can see the brightest future in decades. But we must choose it.

I share the authors' optimism, and their belief that voters will make the right choice in November. This is one of the major reasons I have remained optimistic since late 2008, despite the onslaught of Big Government. Too much government spending, too much income redistribution, and too much oppressive regulation have been major headwinds to economic recovery. With any luck this sea-change in the mood of the electorate that has been brewing since April 2009 will be able to reverse our statist course and eventually restore the economy to health.

And did I mention that I like the idea of Paul Ryan for President in 2012?

HT: Russell Redenbaugh

The recession is officially over

It's not often that an economist makes a near-perfect forecast, so I deserve to take a moment to toot my own horn. In my 2008 year-end forecast, "Predictions for 2009," I wrote that "the economy is going to recover sooner than the market expects, with the bottom in activity coming before mid-2009." Back then the market was expecting a prolonged depression/deflation: 10-yr Treasury yields were approaching 2%, and corporate credit spreads had reached unimaginably high levels.

Today comes the official news, from the National Bureau of Economic Research, that the recession ended in June 2009. You heard it here first, 15 months ago, when I noted in a June 18, 2009 post that "we have very likely seen the end of the recession."

Today comes the official news, from the National Bureau of Economic Research, that the recession ended in June 2009. You heard it here first, 15 months ago, when I noted in a June 18, 2009 post that "we have very likely seen the end of the recession."

Friday, September 17, 2010

This is why stimulus spending is inefficient (and highly so)

According to an article in today's International Business Times, the City of Los Angeles received $111 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, yet created only 55 new jobs. That works out to a cool $2 million per job. Milton Friedman explained this long ago, when he said "you never spend other people's money as wisely as you would your own." It also casts serious doubt on whether the government spending multiplier is even remotely positive.

HT: Drudge

"I'm disappointed that we've only created or retained 55 jobs after receiving $111 million," says Wendy Greuel, the city's controller, while releasing an audit report.

"With our local unemployment rate over 12% we need to do a better job cutting red tape and putting Angelenos back to work,” she added.

According to the report, the Los Angeles Department of Public Works generated only 45.46 jobs (the fraction of a job created or retained correlates to the number of actual hours works) after receiving $70.65 million, while the target was 238 jobs.

Similarly, the city’s department of transportation, armed with a $40.8 million fund, created only 9 jobs in place of an expected 26 jobs.This is a disgrace and an abomination. But if the information is put to good use, it might help send enough new and disciplined people to Congress come November to make a difference.

HT: Drudge

Household Balance Sheet update

Today the Fed released its Flow of Funds report, which includes their calculation of households' net worth (chart above). It doesn't reflect any significant improvement over the levels of last year, and indeed it shows that net worth in the second quarter declined by about $1.5 from the first quarter, largely due to the 12% decline in the stock market. It's interesting to note, however, that the value of households' real estate holdings has been increasing, albeit only modestly, since the first quarter of 2009, and that tracks with the modest increase in the Case-Shiller housing price index over the same period. Also of note is the ongoing modest deleveraging of the household sector, with liabilities in the second quarter of $13.9 trillion, down from $14.3 trillion at the end of 2008.

In addition, the report shows that the household sector has been an important source of financing for our exploding federal deficit: households increased their holdings of Treasury holdings by $820 billion between the end of 2008 and the end of Q2/10. I can't help but think that if it weren't for the huge, deficit-financed federal spending that has occurred over the past few years, households might well have put that money to more productive use. Instead, we have households today holding over $1 trillion of Treasury debt that is yielding a paltry 1.5% on average.

The equity/inflation connection

This chart compares the S&P 500 index (orange line) with Bloomberg's calculation of the market's 5-yr, 5-yr forward inflation expectations (white line; as derived from TIPS and Treasury prices). There's a pretty decent correlation (0.7) between the two, and that implies that whatever causes inflation expectations to rise (though I think it makes more sense to say whatever causes fears of deflation to fall) also causes equity prices to rise, and vice versa.

The correlation has been especially strong in the recent rally. Inflation expectations have risen (deflation fears have fallen), and that has been expressed via a rise in nominal 10-yr Treasury yields and relatively flat TIPS real yields. Rising inflation expectations have moved hand in hand with equity prices. As I mentioned in yesterday's post, the market really believes that weak growth and deflation risk go hand in hand. The news this month has not been as bad as the market had expected, so the market has revised up its outlook for the economy (which is good for stocks) and revised up its outlook for inflation (which is bad for Treasuries).

Deflation again a no-show

Once again deflation has failed to show up in the numbers—it's the dog that didn't bark. I think the equity rally we've seen so far this month has been all about deflation failing to show up and a double-dip recession failing to materialize. The market didn't need good news to rally, it just need the absence of bad news. In other words, the market was priced to the expectation that the news would be bad, and when it wasn't, the market had to reprice upwards. Imagine what might happen if the news were to actually turn positive ...

Then again, perhaps the market is up because the odds of Congress extending the Bush tax cuts are improving.

Whatever the case, it looks like the CPI numbers have seen the low, at least for now. On a 3-month annualized basis, both the headline and the core CPI measures are up more than the year over year numbers (1.7% and 1.4%, respectively).

Meanwhile, corporations continue to make money, and many of them continue to report surprisingly strong profits. Commodity prices are rising across the board. Global trade is expanding. Credit spreads have narrowed significantly and default rates are coming down. Monetary policy all over the world is accommodative. Not one central bank or government is trying to rein in growth, while nearly all are trying (whether intelligently or not) to stimulate growth. Yet despite all these positive signs—and the absence of policy negatives—investors are so afraid of a double-dip recession that they are willing to forego all gains in order to enjoy the safety of cash.

I remain very bullish.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)