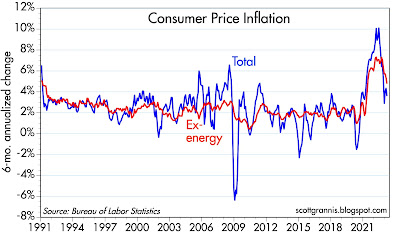

The news today was supposedly disappointing—GDP growth in the first quarter was weaker than expected, while inflation was a bit higher than expected—but I disagree. I see the economy continuing to grow at about a 2% rate and I see inflation falling. Here are two charts which I think give you a better picture of what's happening on the growth and inflation front.

Chart #1

Chart #1 compares the level of real GDP to different trend lines. (Note that the y-axis is logarithmic, so a straight line equates to a constant rate of growth.) From 1965 to 2008, the economy grew by about 3.1% per year on average. But then the economy's growth dynamics changed dramatically following the Great Recession of 2008-09. Since the recovery started in mid-2009, the economy has grown by 2.1% per year on average. Why? I see lots of policy headwinds: Huge increases in tax and regulatory burdens, huge increases in transfer payments, and huge spending on (inefficient) green energy sources, to name just a few, all of which I've discussed at one time or another over the years.

Yes, annualized growth in GDP fell from a 2.6% rate in the fourth quarter to a 1.1% rate in the first quarter, but those are annualized figures which magnify the actual change in the quarterly levels. Note how you can hardly see this change in the blue line on the chart. Moreover, the mini-recession that supposedly happened in the first half of last year is just a wiggle on this chart. The broad growth trend remains about 2%.

The net result is that 14 years of anti-growth policies have cost us over $5 trillion in lost output. Put another way, if nothing had changed since 2008, the economy would be about 25% bigger today—and incomes would also be 25% higher. To be fair, I note that demographics have changed; baby boomers retiring have reduced the growth of the labor force. Nevertheless, it's also true that the labor force participation rate has fallen from 66% in 2008 to now 62.6%. That means that some 5 million people of working age have decided to not work. I've tied that to a big increase in transfer payments, which I explained here.

Chart #2

Finally, it's worth noting that swap spreads and credit spreads continue to be relatively low and well-behaved; there is nothing in those statistics which foreshadows a recession. Corporate profits have been mixed, but there have been some pleasant upside surprises of late in the tech sector (e.g., GOOG and META). A recession is far from being "baked in the cake." Nevertheless, the yield curve is still quite inverted, which means the bond market is pricing in the strong likelihood of a recession and an eventual Fed ease. In fact, the bond market assigns a high probability of another 25-50 bps rate hike at next week's FOMC meeting.

The Fed may well hike next week, but that would be a mistake in my view. If they do (because they want to regain some of the credibility they've lost over the past year or so), it won't be a surprise to the market. But if they don't, that would be a nice surprise. In any event, I prefer to bet on what is going on in the economy, not what is going on in the heads of the FOMC members. The Fed may be late to react to the economic realities, but react they will, and that's the bigger story I prefer to follow.

An economy growing at a modest 2% rate, inflation by all measures declining significantly, combined with interest rates that are high enough to cause pain in many sectors of the economy, do not add up to a rationale for another rate hike next week.

UPDATE (April 28): Today we received the March figures for the Personal Consumption Expenditure Deflators, which are measures of inflation at the individual level which are arguably superior to the CPI, mainly because they cover a broader basket of goods and services and the weightings of the components adjust dynamically as the economy and consumer habits change. Over long periods, the PCE deflator tends to register about 0.5% less inflation per year than the CPI, which is why many believe that the CPI tends to overstate inflation. It also explains why the Fed prefers to focus on the PCE deflator even though they talk a lot about the CPI. Chart #3 compares the two measures on a year over year basis.

Chart #3

Chart #4

Chart #4 looks at the 3 components of the PCE deflator: services, durable goods, and non-durable goods. It starts at 1995 since that was the year after China devalued its currency for the last time and simultaneously began its long march to become the world's biggest exporter of durable goods. It also marked the first year that the durable goods component of the PCE deflator turned negative. China did become a global powerhouse in durable goods and in the process they drove durable goods prices lower worldwide. US durable goods prices today are 31% lower than they were at the beginning of 1995.

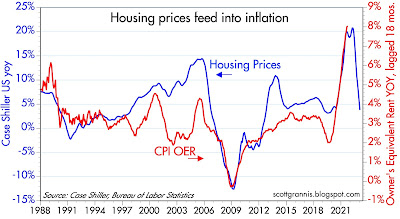

Another point I want to make here is that durable and nondurable goods prices today are unchanged since last June, which not coincidentally was the high-water mark for the year over year change in the CPI and the PCE deflator. In other words, service sector prices are the sole source of whatever inflation has occurred in the US for the past 9 months. It's also important to point out that the cost of shelter (housing prices and rents) is a significant portion of service sector prices, and as this post notes, that component of the CPI peaked last month. In the months to come, with housing and rental costs falling and durable and nondurable goods prices flat, overall inflation is almost sure to continue to fall.