Fear is slowly subsiding as reflected by a declining VIX index. Stock prices are rising, and probably have much further to go on the upside. The market has digested all the bad news, and the financial market is slowly healing its wounds of the past month. This is all very healthy, and this is no time to be pessimistic.

Fear is slowly subsiding as reflected by a declining VIX index. Stock prices are rising, and probably have much further to go on the upside. The market has digested all the bad news, and the financial market is slowly healing its wounds of the past month. This is all very healthy, and this is no time to be pessimistic.

Friday, October 31, 2008

Fear subsides, prices rise

Fear is slowly subsiding as reflected by a declining VIX index. Stock prices are rising, and probably have much further to go on the upside. The market has digested all the bad news, and the financial market is slowly healing its wounds of the past month. This is all very healthy, and this is no time to be pessimistic.

Fear is slowly subsiding as reflected by a declining VIX index. Stock prices are rising, and probably have much further to go on the upside. The market has digested all the bad news, and the financial market is slowly healing its wounds of the past month. This is all very healthy, and this is no time to be pessimistic.

Price stability is a dream

The nominal yield on a 5-year Treasury bond and the real yield on a 5-year TIPS bond are identical today, which means that the bond market is expecting consumer price inflation to average zero over the next five years. This chart is a reminder that price stablity is a long way away from where we are today. The Fed has told us that the personal consumption expenditures deflator (both with and without energy) is the preferred measure of inflation, since it is a broad measure of prices and doesn't suffer from some of the biases that the CPI has. Inflation have been above the Fed's 1-2% target for over four years now. I remain very skeptical that inflation will fall as much as the market expects.

The nominal yield on a 5-year Treasury bond and the real yield on a 5-year TIPS bond are identical today, which means that the bond market is expecting consumer price inflation to average zero over the next five years. This chart is a reminder that price stablity is a long way away from where we are today. The Fed has told us that the personal consumption expenditures deflator (both with and without energy) is the preferred measure of inflation, since it is a broad measure of prices and doesn't suffer from some of the biases that the CPI has. Inflation have been above the Fed's 1-2% target for over four years now. I remain very skeptical that inflation will fall as much as the market expects.The bond market has never been very good at predicting inflation. That's because of the pervasive view that a weak economy will reduce inflation while a very strong economy will push it up. That has the causality all wrong. Rising inflation is bad for growth, since it tempts people to speculate (e.g., by buying homes, gold, commodities and other currencies), while low inflation is good for growth, since it encourages people to invest (e.g. by buying things which lower costs and increase productivity).

Short sales (real estate)

I thought I was on top of what was happening in the real estate market, but yesterday I learned I was ignorant of what is probably one of the most significant trends sweeping the real estate market in the past year: the short sale. Instead of foreclosure, homeowners who find themselves under water on their mortgage (i.e., they owe more than their home is worth) may be able to convince their bank to agree to a short sale. The bank agrees to accept the proceeds of the sale and may then consider the debt to be satisfied. This avoids the messiness of foreclosures or evictions, and may allow the borrower to avoid a blotch on his or her credit history. If done right, it can be a win-win for all concerned, mitigating the misfortune of losing one's home. Another benefit is that these sales are going on all over the place, and they don't require any government bailout money. It's the private sector's answer to the problem of falling home prices.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Unemployment claims have stabilized

Weekly initial claims for unemployment have not increased at all in the past five weeks, and the much-touted 4-week moving average has fallen for the past three weeks. Claims today are about as high as they were at the peak of the last recession, which was the mildest on record. This confirms what the GDP data are telling us: to date the economy has experienced only a modest slowdown.

Weekly initial claims for unemployment have not increased at all in the past five weeks, and the much-touted 4-week moving average has fallen for the past three weeks. Claims today are about as high as they were at the peak of the last recession, which was the mildest on record. This confirms what the GDP data are telling us: to date the economy has experienced only a modest slowdown.

Is Obama a socialist?

Don Boudreaux has a thoughtful article which concludes that, while not a socialist in the classic sense, Obama shares many of socialism's beliefs.

A principal promise of socialism was to replace the alleged uncertainty of markets with the comforting certainty of a central economic plan. Of course, socialism utterly failed. By making the state the arbiter of economic value and social justice, as well as the source of rights, it deprived individuals of their liberty...

Anyone who speaks glibly of "spreading the wealth around" sees wealth not as resulting chiefly from individual effort, initiative, and risk-taking, but from great social forces beyond any private producer's control. Wealth, in this view, is produced principally by society. (And) because wealth is produced mostly by society (rather than by individuals), taxing high-income earners more heavily will do little to reduce total wealth production.

Consider the words of longtime Socialist Party of America presidential candidate Norman Thomas: "The American people will never knowingly adopt socialism, but under the name of liberalism, they will adopt every fragment of the socialist program until one day America will be a socialist nation without ever knowing how it happened." In addition to Medicare, Social Security, and other entitlement programs, the gathering political momentum toward single-payer healthcare – which Obama has proclaimed is his ultimate goal – shows the prescience of Thomas's words.

Modest economic slowdown

The contrast between rhetoric and reality is huge. With all the references to how this is the worst crisis since the Depression, you'd think the numbers would be awful. Well, they're not. Third-quarter GDP figures were released today, and it seems the economy shrunk at an annualized rate of -0.25% (translation: the US economy shrank by an infinitesimal 0.06% in the third quarter—so far within the range of rounding errors that it is meaningless to even say that it shrank). This may be the beginnings of a recession (which typically requires two quarters of negative growth), but if so, it looks pretty mild so far.

The contrast between rhetoric and reality is huge. With all the references to how this is the worst crisis since the Depression, you'd think the numbers would be awful. Well, they're not. Third-quarter GDP figures were released today, and it seems the economy shrunk at an annualized rate of -0.25% (translation: the US economy shrank by an infinitesimal 0.06% in the third quarter—so far within the range of rounding errors that it is meaningless to even say that it shrank). This may be the beginnings of a recession (which typically requires two quarters of negative growth), but if so, it looks pretty mild so far.This chart gives some history for perspective. Things were wild and wooly back in the 1970s, when GDP growth swung between -5% and +10% routinely. Since then, the economy has been on a stabilizing trend. I figure it has a lot to do with the ongoing development of our financial markets. It may be fashionable to blame free markets for our recent woes, but the truth is probably just the opposite: thanks to free markets we have developed instruments, like derivatives and credit default swaps, that very efficiently distribute risk among investors all over the world. Financial markets now act like a shock absorber for the real economy, minimizing the impact of shocks on the body politic.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Fear is the driver

This chart suggests that one of the biggest reasons for the market's collapse is fear. The red line (VIX) is a measure of the implied volatility of equity options, which in turn is highly correlated to the market's fears, doubts, and uncertainties. The higher the fear factor (which shows up as a declining red line since I have inverted the scale), the more people are willing to pay for the protection of things like put options, and the higher the VIX. Fear also contributes to a lack of liquidity and that too can depress prices.

This chart suggests that one of the biggest reasons for the market's collapse is fear. The red line (VIX) is a measure of the implied volatility of equity options, which in turn is highly correlated to the market's fears, doubts, and uncertainties. The higher the fear factor (which shows up as a declining red line since I have inverted the scale), the more people are willing to pay for the protection of things like put options, and the higher the VIX. Fear also contributes to a lack of liquidity and that too can depress prices.This chart is quite similar to the one comparing swap spreads to equities in my post last night. The main difference is that swap spreads are typically a leading indicator, whereas the VIX is a coincident indicator.

If fear and uncertainty subside, there is a lot of room for equity prices to move higher. Fear is easier to vanquish than depression. We're not talking depression by any stretch of the imagination.

Fed rate cut is likely, but that's not what matters

Everyone seems very excited about the likelihood of another Fed rate cut, but that's missing the forest for the trees. The seeds of a recovery from this financial crisis have already been sown. Whether the Fed funds rate target is 1.5% or 1% is not going to make much of a difference. The big changes to focus on have already happened:

The Fed has quadrupled the amount of bank reserves in the system in the past six weeks, enough to easily accommodate the world's sudden thirst for dollars.

The Fed has pumped $100 billion or so into the Commercial Paper market in the past two days, in order to alleviate a drastic shortage of liquidity.

Swap spreads are way down from their highs, reflecting an easing of tensions in the institutional money markets.

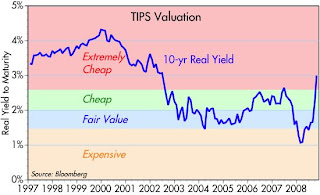

Real yields on 5-year TIPS have doubled in the past three weeks, ostensibly because of collapsing commodity prices and deflation fears, but really because the prospects for the economy have brightened considerably (the economy is much more likely to grow with oil at $65 than with oil at $150).

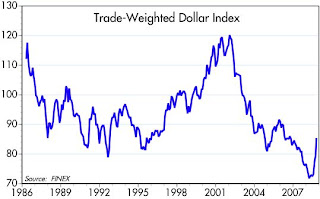

The dollar has jumped almost 20% in the past two months, pulling back from the abyss it was headed into earlier this year and reflecting a more balanced assessment of the economy's prospects.

The Fed has quadrupled the amount of bank reserves in the system in the past six weeks, enough to easily accommodate the world's sudden thirst for dollars.

The Fed has pumped $100 billion or so into the Commercial Paper market in the past two days, in order to alleviate a drastic shortage of liquidity.

Swap spreads are way down from their highs, reflecting an easing of tensions in the institutional money markets.

Real yields on 5-year TIPS have doubled in the past three weeks, ostensibly because of collapsing commodity prices and deflation fears, but really because the prospects for the economy have brightened considerably (the economy is much more likely to grow with oil at $65 than with oil at $150).

The dollar has jumped almost 20% in the past two months, pulling back from the abyss it was headed into earlier this year and reflecting a more balanced assessment of the economy's prospects.

Capital spending continues to grow

Capital goods are the things that businesses invest in to make people more productive (e.g., computers, machinery, factories). As such they are the seed corn of future growth. The impressive thing about business investment is that it has not fallen as it usually does in recessions. It may not be growing a lot, but considering the pervasive doom and gloom and the supposed difficulty in obtaining financing (which, as I've argued, is largely a myth), it's pretty impressive and at the very least suggests that businesses remain optimistic about their own future. A very healthy sign, and one reason I say the jury is still out on whether this is a recession.

Capital goods are the things that businesses invest in to make people more productive (e.g., computers, machinery, factories). As such they are the seed corn of future growth. The impressive thing about business investment is that it has not fallen as it usually does in recessions. It may not be growing a lot, but considering the pervasive doom and gloom and the supposed difficulty in obtaining financing (which, as I've argued, is largely a myth), it's pretty impressive and at the very least suggests that businesses remain optimistic about their own future. A very healthy sign, and one reason I say the jury is still out on whether this is a recession.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Are swaps forecasting a huge equity rally? (2)

I'm not giving up on this chart yet, especially after today's rally. The premise of the chart is that the financial market logjam which resulted in record-high swap spreads, credit spreads and the TED spread, not to mention a woeful lack of liquidity in the institutional money market, was a major contributing factor to sowing fear, uncertainty and doubt throughout world markets in general, severely depressing valuations for corporate bonds and stocks and pushing volatility (e.g., the VIX index) to record highs.

I'm not giving up on this chart yet, especially after today's rally. The premise of the chart is that the financial market logjam which resulted in record-high swap spreads, credit spreads and the TED spread, not to mention a woeful lack of liquidity in the institutional money market, was a major contributing factor to sowing fear, uncertainty and doubt throughout world markets in general, severely depressing valuations for corporate bonds and stocks and pushing volatility (e.g., the VIX index) to record highs.The thrust of government bailout efforts is to relieve some of this stress, and it appears that things are beginning to loosen up. Swap spreads are always the first to react to changes in systemic risk, so the rally today could be more confirmation that underlying conditions are starting to improve.

Could the rally really be as strong as the chart suggests? That sounds like a lot to hope for, but I don't think it's unreasonable to expect some dramatic improvements. To date this crisis has been mainly a financial market event, and it has only partially spilled over to the real economy. Big financial crises do not necessarily predict or foreordain economic depressions. And most importantly, equity valuations today appear to be extraordinarily depressed by fear that could be alleviated.

Reminder: stocks are very cheap

This is my version of an equity valuation model that is very similar to the "Fed Model" and the one used by Art Laffer for many years. It's based on the assumption that the best measure of corporate profits is to be found in the National Income and Product Accounts. It capitalizes those profits using the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds, and compares that theoretical measure of value to the actual value as measured by the S&P 500 index.

This is my version of an equity valuation model that is very similar to the "Fed Model" and the one used by Art Laffer for many years. It's based on the assumption that the best measure of corporate profits is to be found in the National Income and Product Accounts. It capitalizes those profits using the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds, and compares that theoretical measure of value to the actual value as measured by the S&P 500 index.Based on this model, stocks have NEVER been so cheap. That's another way of saying that this market is priced to the expectation that we will be in a depression that will cause massive bankruptcies and gargantuan losses all over the world. (World stock market capitalization yesterday was down 55% from its year-ago high.)

You've got to be a real pessimist to not like stocks at these levels.

Financial logjam appears to be breaking up

More signs that rescue efforts are gaining traction:

Yesterday the Fed began buying Commercial Paper (a popular way for many larger corporations to fund their short-term cash needs), and CP issuance jumped to a record daily high of $67 billion. Yields on 90-day financial CP (the only part of the CP market that had collapsed in recent months) fell sharply as issuance soared. New money is getting into the system, and this should reassure markets that there are fewer default landmines out there waiting to blow up unsuspecting investors.

The VIX index has retreated to 70 today, down from its high of 90 last Friday. Swap spreads are still high, but moving down in fits and starts. Likewise the TED spread. The Fed funds rate is a mere 0.5%, a sign that the Fed is happy to supply cheap money to whomever wants it, and that in turn means they are likely to lower the official target rate tomorrow.

Stocks may be picking up on the good news. The Dow is up 10% from its intraday, panicked low on October 10th.

UPDATE: Looks like the Dow today closed 15% above its Oct. 10th low.

Yesterday the Fed began buying Commercial Paper (a popular way for many larger corporations to fund their short-term cash needs), and CP issuance jumped to a record daily high of $67 billion. Yields on 90-day financial CP (the only part of the CP market that had collapsed in recent months) fell sharply as issuance soared. New money is getting into the system, and this should reassure markets that there are fewer default landmines out there waiting to blow up unsuspecting investors.

The VIX index has retreated to 70 today, down from its high of 90 last Friday. Swap spreads are still high, but moving down in fits and starts. Likewise the TED spread. The Fed funds rate is a mere 0.5%, a sign that the Fed is happy to supply cheap money to whomever wants it, and that in turn means they are likely to lower the official target rate tomorrow.

Stocks may be picking up on the good news. The Dow is up 10% from its intraday, panicked low on October 10th.

UPDATE: Looks like the Dow today closed 15% above its Oct. 10th low.

David vs Goliath (AAPL vs MSFT)

I've been a fan of Apple computers ever since 1987, when I bought my first Mac. I've used Macs and PCs almost every day since. I'm doing all of this on a Mac laptop that is also running (simultaneously) Windows XP, thanks to virtualization software from VMware Fusion. If you get a Mac you can do it all, you no longer have to choose one or the another. It's been fun to watch Apple catch up to Microsoft over the past five years. Microsoft can't figure out how to innovate, whereas Apple is King of the Hill when it comes to innovation. If current trends persist, and I think they should, we could see Apple surpass Microsoft's market cap within a few years. That would be one of the great David vs. Goliath stories of the modern age. It's also a good illustration of how free markets lead to creative destruction.

I've been a fan of Apple computers ever since 1987, when I bought my first Mac. I've used Macs and PCs almost every day since. I'm doing all of this on a Mac laptop that is also running (simultaneously) Windows XP, thanks to virtualization software from VMware Fusion. If you get a Mac you can do it all, you no longer have to choose one or the another. It's been fun to watch Apple catch up to Microsoft over the past five years. Microsoft can't figure out how to innovate, whereas Apple is King of the Hill when it comes to innovation. If current trends persist, and I think they should, we could see Apple surpass Microsoft's market cap within a few years. That would be one of the great David vs. Goliath stories of the modern age. It's also a good illustration of how free markets lead to creative destruction.

Gasoline prices plunge -- very good news

Not all the news is bad. Gasoline prices nationwide have plunged $1 per gallon in the past month, to $2.75. Last July they were around $4.25, and in part of Los Angeles they were approaching $5 per gallon. The best message here is that markets work. Some times prices get out of whack but they do so in order to bring supply and demand back into balance. With oil prices now around $60/barrel, gasoline prices will probably fall some more.

Not all the news is bad. Gasoline prices nationwide have plunged $1 per gallon in the past month, to $2.75. Last July they were around $4.25, and in part of Los Angeles they were approaching $5 per gallon. The best message here is that markets work. Some times prices get out of whack but they do so in order to bring supply and demand back into balance. With oil prices now around $60/barrel, gasoline prices will probably fall some more.

Another measure of fear (4)

Markets continue to be extremely pessimistic about the future, and this chart is one reason why. This is a measure of commodity shipping costs. As recently as last June, strong global growth collided with a dearth of shipping capacity to produce sky-high prices. Today, shippers are idling ships and slowing the speed at which they travel. Global commerce has slowed sharply as uncertainty grips nearly everyone. If global commerce actually ground to a halt this would replicate the conditions that led to the depression of the 1930s.

Markets continue to be extremely pessimistic about the future, and this chart is one reason why. This is a measure of commodity shipping costs. As recently as last June, strong global growth collided with a dearth of shipping capacity to produce sky-high prices. Today, shippers are idling ships and slowing the speed at which they travel. Global commerce has slowed sharply as uncertainty grips nearly everyone. If global commerce actually ground to a halt this would replicate the conditions that led to the depression of the 1930s.Consumer confidence numbers released today plunged to their lowest level ever, and the data go back to 1967. Everyone is scared, everyone is pulling back.

The Smoot-Hawley tariffs sparked a global tariff war which shut down commerce back then, but nothing like that has happened today. It's mainly fear generated by the panic in financial markets. Markets can right themselves given time, and confidence can be restored. We don't have to undo any nasty legislation. It shouldn't be too hard to get things going again.

Monday, October 27, 2008

Subprime factoids -- we've seen most of the bad news

I was just looking through a fascinating collection of data relating to the mortgage disaster put together by the Milken Institute. At the peak of subprime mortgage lending in 2006, there were about $1.2 trillion of outstanding subprime mortgages. By March of this year that had dropped to just under $900 billion. To date, financial institutions around the world have recorded losses (most of them related to subprime lending) of just over $500 billion.

The eventual losses suffered by holders of defaulted mortgages will be equal to the original value of the mortgages less the recovery value of the homes that are sold in foreclosure. Let's be very pessimistic and assume that every single subprime mortgage ever made was a zero down loan; that they all default; and that the foreclosed homes all sell for only 50% of their original value. That would translate into total subprime losses of roughly $600 billion.

That's most likely the upper limit for subprime losses. Derivatives and leverage can't magnify these losses. Derivatives only distribute losses. Leverage magnifies the losses of the leveraged loser, but leverage doesn't increase the total losses to the system.

So, it would appear that we are closing in on the tail end of the subprime-related losses. The vast bulk of the losses have been taken, realized, and written down. There's not much left to this sad and tragic story. But it sure seems like a pretty small tail to be wagging the big global dog.

The eventual losses suffered by holders of defaulted mortgages will be equal to the original value of the mortgages less the recovery value of the homes that are sold in foreclosure. Let's be very pessimistic and assume that every single subprime mortgage ever made was a zero down loan; that they all default; and that the foreclosed homes all sell for only 50% of their original value. That would translate into total subprime losses of roughly $600 billion.

That's most likely the upper limit for subprime losses. Derivatives and leverage can't magnify these losses. Derivatives only distribute losses. Leverage magnifies the losses of the leveraged loser, but leverage doesn't increase the total losses to the system.

So, it would appear that we are closing in on the tail end of the subprime-related losses. The vast bulk of the losses have been taken, realized, and written down. There's not much left to this sad and tragic story. But it sure seems like a pretty small tail to be wagging the big global dog.

Spreading the wealth only makes us all poorer (2)

In case you've missed it, the blogosphere is buzzing over the discovery of a 2001 interview on Chicago NPR that revealed yet more of Obama's socialist/marxist core instincts. You can check it out here, and here is the transcript of the relevant portion:

... the Supreme Court never ventured into the issues of redistribution of wealth, and of more basic issues such as political and economic justice in society. To that extent, as radical as I think people try to characterize the Warren Court, it wasn’t that radical. It didn’t break free from the essential constraints that were placed by the founding fathers in the Constitution, at least as its been interpreted and Warren Court interpreted in the same way, that generally the Constitution is a charter of negative liberties. Says what the states can’t do to you. Says what the Federal government can’t do to you, but doesn’t say what the Federal government or State government must do on your behalf, and that hasn’t shifted and one of the, I think, tragedies of the civil rights movement was, um, because the civil rights movement became so court focused I think there was a tendancy to lose track of the political and community organizing and activities on the ground that are able to put together the actual coalition of powers through which you bring about redistributive change. In some ways we still suffer from that.Obama apparently favors an extremely activist court that would rewrite the Constitution, granting unheard of new powers to government to "spread the wealth."

TIPS are a steal (2)

Plunging commodity prices have convinced some traders that inflation is going to be negative for the next 5 years. As a result, the prices of TIPS have plunged, and their real yields have risen. 5-year TIPS being auctioned today will have a real yield that is actually higher than the nominal yield on 5-year Treasuries. The iShares LehmanUS Treasury Inflation Protected Securities Fund (TIP) today is selling at its lowest level (closing price) ever.

Plunging commodity prices have convinced some traders that inflation is going to be negative for the next 5 years. As a result, the prices of TIPS have plunged, and their real yields have risen. 5-year TIPS being auctioned today will have a real yield that is actually higher than the nominal yield on 5-year Treasuries. The iShares LehmanUS Treasury Inflation Protected Securities Fund (TIP) today is selling at its lowest level (closing price) ever. With real yields high and expected inflation extremely low, TIPS add up to a very cheap way to buy insurance against inflation.

With real yields high and expected inflation extremely low, TIPS add up to a very cheap way to buy insurance against inflation.

Global equities seesaw -- and exaggerate

This chart compares the S&P 500 to Germany's DAX index; note that the y-axis has a similar range of magnitude for both equity markets. European equities have been more volatile than US markets mainly because of swings in the value of the dollar. Abstracting from the dollar's swings, both German and US equity markets have tracked each other pretty closely. In short, this is globalization, and we're all in this together.

This chart compares the S&P 500 to Germany's DAX index; note that the y-axis has a similar range of magnitude for both equity markets. European equities have been more volatile than US markets mainly because of swings in the value of the dollar. Abstracting from the dollar's swings, both German and US equity markets have tracked each other pretty closely. In short, this is globalization, and we're all in this together.The problem that started with declining home prices in the US and was magnified by subprime mortgage loans has now spread to the entire world. The market value of all the stocks in the world, when measured in dollars, is now down a staggering 53% from the high one year ago. World market capitalization has fallen from $62.6 trillion to $29.6 trillion, a loss of $33 trillion! And the pundits are talking about a global recession getting underway.

A thought experiment: let's say that the value of all the homes owned by US households is down 25% from the high, which is probably a stretch but would be in line with the fall registered by the Case-Shiller home price index. Using the Fed's data, that would mean US homes have lost $5 trillion in aggregate value and are now worth only $15 trillion (which is what they were worth 5 years ago).

I'm having trouble understanding how a loss of $5 trillion in the US housing market, while certainly not trivial, could trigger a loss of $33 trillion in global stock markets. Something is out of whack, and I think equities have over-reacted.

How taxes affect the incentive to work

Greg Mankiw has a terrific post that sums up how the tax proposals of McCain and Obama would affect his incentive to work more on the margin.

If there were no taxes, then $1 earned today would yield my kids $28. That is simply the miracle of compounding.

Under the McCain plan, a dollar earned today yields my kids $4.81. That is, even under the low-tax McCain plan, my incentive to work is cut by 83 percent compared to the situation without taxes.

Under the Obama plan, a dollar earned today yields my kids $1.85. That is, Obama's proposed tax hikes reduce my incentive to work by 62 percent compared to the McCain plan and by 93 percent compared to the no-tax scenario.

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Things I'd like to hear

There is plenty of money out there. This is not a problem of a shortage of money, it's a shortage of buyers. Buyers are lacking because there is a problem of confidence, a lack of trust. To fix that, we need less uncertainty. Accordingly, I'd like to hear the following very soon:

First, Obama should explain to the world that he understands that the financial markets are in great turmoil. He should acknowledge that this poses a threat to the global economy. He should say that he understands that this is therefore not a time to try to "change the world" with higher taxes on anyone, or any kind of radical restructuring of the American economy. He should promise to forego any attempts to raise taxes, especially taxes on capital, and only consider such a move once the economy and the financial markets are back on their feet. We have far bigger problems today than redistributing wealth are likely to solve.

Second, someone in the government should make it clear to the world's financial markets that the $1 trillion outstanding debt of Government Sponsored Entities such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae are now 100% backed by the full faith and credit of the US government. This is not a time to mince words (e.g., is the debt of the GSEs is "explicity" or "effectively" guaranteed by the US government?). The world's investors were shocked to learn that shareholders in Freddie and Fannie were wiped out when the government placed these GSEs in conservatorship, so they have reason to wonder whether the debt holders will be wiped out or not. I don't think there's any question: for the US government to not honor GSE debt would be a mistake of disastrous proportions; it would do unthinkable harm to the reputation of our government and undermine the very foundations of global financial markets that rely on US government guaranteed debt as the risk-free gold standard. Could this waffling have anything to do with the elections? Would assuming full responsibility for GSE debt imply adding that debt to the existing national debt? To be sure, adding $1 trillion to our national debt would not be the end of the world, but it certainly wouldn't burnish Bush's legacy. But I sure hope this isn't the reason for the semantics. (What I'm referring to here is the source of the fear that has driven the credit spreads on GSEs to historically wide levels, even as swap spreads have declined.)

Such are the issues that have investors trembling all over the world. And to think these fears could be banished with just the right combination of words....

Anyone have suggestions for other critical issues that need to be clarified?

First, Obama should explain to the world that he understands that the financial markets are in great turmoil. He should acknowledge that this poses a threat to the global economy. He should say that he understands that this is therefore not a time to try to "change the world" with higher taxes on anyone, or any kind of radical restructuring of the American economy. He should promise to forego any attempts to raise taxes, especially taxes on capital, and only consider such a move once the economy and the financial markets are back on their feet. We have far bigger problems today than redistributing wealth are likely to solve.

Second, someone in the government should make it clear to the world's financial markets that the $1 trillion outstanding debt of Government Sponsored Entities such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae are now 100% backed by the full faith and credit of the US government. This is not a time to mince words (e.g., is the debt of the GSEs is "explicity" or "effectively" guaranteed by the US government?). The world's investors were shocked to learn that shareholders in Freddie and Fannie were wiped out when the government placed these GSEs in conservatorship, so they have reason to wonder whether the debt holders will be wiped out or not. I don't think there's any question: for the US government to not honor GSE debt would be a mistake of disastrous proportions; it would do unthinkable harm to the reputation of our government and undermine the very foundations of global financial markets that rely on US government guaranteed debt as the risk-free gold standard. Could this waffling have anything to do with the elections? Would assuming full responsibility for GSE debt imply adding that debt to the existing national debt? To be sure, adding $1 trillion to our national debt would not be the end of the world, but it certainly wouldn't burnish Bush's legacy. But I sure hope this isn't the reason for the semantics. (What I'm referring to here is the source of the fear that has driven the credit spreads on GSEs to historically wide levels, even as swap spreads have declined.)

Such are the issues that have investors trembling all over the world. And to think these fears could be banished with just the right combination of words....

Anyone have suggestions for other critical issues that need to be clarified?

Friday, October 24, 2008

Home sales activity picking up

As noted before, home sales are picking up, and look to have bottomed out. This has got to be very good news, since it means housing prices have fallen to levels that are now allowing the market to clear. If prices find a bottom soon, this will remove a huge source of uncertainty from the market. I keep thinking that with the Fed ensuring that money is available to those who want it, the market can sort out the subprime losses and life can go on, and this financial nightmare will soon fade into the past.

As noted before, home sales are picking up, and look to have bottomed out. This has got to be very good news, since it means housing prices have fallen to levels that are now allowing the market to clear. If prices find a bottom soon, this will remove a huge source of uncertainty from the market. I keep thinking that with the Fed ensuring that money is available to those who want it, the market can sort out the subprime losses and life can go on, and this financial nightmare will soon fade into the past.One hurdle that has popped up of late is government waffling on whether the debt of Freddie and Fannie is actually backed by the US government or not. If the government were to walk away from the mountain of debt these agencies have issued, it would be a true nightmare of unthinkable proportions. Clarification of this matter is needed urgently.

Thursday, October 23, 2008

Enter quantitative easing

As this chart graphically illustrates, the Fed has entered "quantitative easing" mode with a vengeance. The only parallel to this that I'm aware of is when the Japanese central bank doubled bank reserves in 2001 and again in 2002, and then increased them another 50% in 2003. That was considered to be beyond the realm of the possible for developed countries back then, but now the Fed has quadrupled bank reserves (according to my estimates) over the past six weeks!

As this chart graphically illustrates, the Fed has entered "quantitative easing" mode with a vengeance. The only parallel to this that I'm aware of is when the Japanese central bank doubled bank reserves in 2001 and again in 2002, and then increased them another 50% in 2003. That was considered to be beyond the realm of the possible for developed countries back then, but now the Fed has quadrupled bank reserves (according to my estimates) over the past six weeks!It took about four years for a massive expansion of raw money supply to reverse Japan's deflation, but reverse it did, and inflation in Japan is now 2% instead of being negative. I think we can safely assume that it won't take that long for the Fed's current efforts to get us out of this financial crisis. But some intense prayer might not hurt in the meantime.

The scope of the Fed's response to this crisis is beyond anything that could have been imagined just weeks ago, so we can only speculate about the future might hold at this point. But this we do know: this financial crisis (as I've mentioned previously) is all about people wanting fewer things and more money (many describe this as a massive deleveraging of the system). And the Fed is determined that people will not be disappointed.

The demand for money has soared in recent weeks as investors have fled equities, commodities, gold and foreign currencies in favor of cash. By flooding the banking system with reserves, the Fed is responding to this increased demand for money and they are taking no chances—they are supplying reserves in excess of the market's demand for them, as evidenced by the fact that the federal funds rate has traded below the Fed's target almost every day since they began their quantitative easing. In effect, they have abandoned their fed funds targeting procedure in favor of simply throwing reserves into the system as fast as they can figure out which assets to buy to expand their balance sheet.

Eventually (and that is the rub, because we don't know how long this will take), a massive expansion of bank reserves should at the very least forestall or reverse any deflationary tendencies that might result from the current financial crisis. As I have said before, now is not the time to worry about deflation.

If the crux of the current crisis is that there is an excess of "things" (e.g., equities, real estate, commodities, gold) because people want more money instead, the Fed is all but guaranteeing that there will be no shortage of money available to those willing to buy "things" from those wishing to sell them.

Housing price bottom is approaching

This first chart shows the housing price bubble. It uses the broadest measure of US home prices, as calculated by OFHEO, and I have adjusted it for inflation as measured by the personal consumption deflator. The 1.3% trend line is my guess for how much real home prices tend to rise over time, given increases in real earnings and a tendency for homes to increase in size. The difference between actual and trend would be the size of the current bubble. If the trend holds, then at the peak of the market a few years ago, prices were "overvalued" by about one-third. If prices overshoot on the downside as they have in the past, they could end up falling by 35% in inflation-adjusted terms from their peak. Unfortunately, this would suggest we're only in the initial stages of a protracted decline.

This first chart shows the housing price bubble. It uses the broadest measure of US home prices, as calculated by OFHEO, and I have adjusted it for inflation as measured by the personal consumption deflator. The 1.3% trend line is my guess for how much real home prices tend to rise over time, given increases in real earnings and a tendency for homes to increase in size. The difference between actual and trend would be the size of the current bubble. If the trend holds, then at the peak of the market a few years ago, prices were "overvalued" by about one-third. If prices overshoot on the downside as they have in the past, they could end up falling by 35% in inflation-adjusted terms from their peak. Unfortunately, this would suggest we're only in the initial stages of a protracted decline.This might be a better way to look at it: The second chart shows another version of inflation-adjusted home prices, as measured by the Case-Shiller folks and adjusted for the same measure of inflation. This index covers only properties in the 20 largest metropolitan markets of the country, whereas OFHEO covers the whole country. But that's probably not a bad thing, since the big cities tend to be the areas where prices increased the most and have now fallen the most and the fastest. In any event, the Case-Shiller index appears to respond much more quickly to changing conditions than the OFHEO index.

Even so, the official description of this index says that it is "calculated monthly using a three-month moving average and published with a two month lag." With the latest data being in July, that means this index is only giving us the average of home prices during the months of May through July. So, if prices were moving down throughout that period, as seems quite likely, then the index is overstating the level of prices. I have extrapolated the index through the end of this year, in order to get a feel for what prices might be doing right now. I've assumed that the price index will fall each month by the average of monthly declines from January through July, and inflation will be essentially zero given the big decline in energy prices. Both of these are pretty conservative assumptions. The bottom line is that this measure of inflation-adjusted prices today has probably fallen 30% from the high. That is the same order of magnitude as the size of the bubble suggested in the first chart. If true, this would mean that in major markets around the country we may be getting close to the end of the bursting of the housing bubble.

Even so, the official description of this index says that it is "calculated monthly using a three-month moving average and published with a two month lag." With the latest data being in July, that means this index is only giving us the average of home prices during the months of May through July. So, if prices were moving down throughout that period, as seems quite likely, then the index is overstating the level of prices. I have extrapolated the index through the end of this year, in order to get a feel for what prices might be doing right now. I've assumed that the price index will fall each month by the average of monthly declines from January through July, and inflation will be essentially zero given the big decline in energy prices. Both of these are pretty conservative assumptions. The bottom line is that this measure of inflation-adjusted prices today has probably fallen 30% from the high. That is the same order of magnitude as the size of the bubble suggested in the first chart. If true, this would mean that in major markets around the country we may be getting close to the end of the bursting of the housing bubble.Caveat: this analysis has lots of apples vs oranges problems (e.g., comparing two very different indices), and I have made assumptions which could be wrong. But I do think it is reasonable to say that we have seen the bulk of the decline of housing prices by now. The August data for the Case Shiller index will be released next Tuesday.

My concerns with Obama

As a fan of free markets, liberty, and limited government, I have grave concerns about Obama as president. I acknowledge his depth of intellect, and I also note that he has changed his views on a wide range of subjects in the past year, moving more to the center from the extreme left. But there are a handful of core beliefs and characteristics of his that I find quite disturbing. Karl Rove pinned this down in his WSJ column today.

And all of this will detract from individual liberty and free markets as it grants more power to government.

Wanting to raise taxes -- anyone's taxes -- in a slowdown is a warning sign of a misguided economic philosophy. Obama's proposal to redistribute wealth is a warning of indifference or hostility to enterprise.To these I would add: Obama's strong belief in man-made global warming is a warning that the government will assume much broader control over economic activity (e.g., via limits on CO2 emissions). Obama's advocacy of youth corps and community service is a warning that the government will have more power to indoctrinate the young. Obama's belief in the power of government to do good is a warning that he will invariably choose more regulation and more government bureaucracy rather than less as a solution to problems that crop up.

Three years ago, Mr. McCain called for stricter oversight of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, warning their risky practices threatened our economy and could cost taxpayers billions. Mr. Obama and congressional Democrats ignored these signs and opposed reform.

Obama's health-care plan is a warning that government will have more, not less, to say about your health care if he has his way.

Obama's dismissal of offshore drilling and opposition to nuclear power are warning signs for an economy whose growth depends on affordable energy.

The absence of a single significant instance in which Mr. Obama cooperated in a bipartisan manner in the Senate is a warning sign. And so is his refusal to break with his party or its interest groups on any issue of substance.

And all of this will detract from individual liberty and free markets as it grants more power to government.

Unemployment claims suggest mild recession

Weekly claims for unemployment have risen about as much as they did in the 2001 recession, and that was the mildest on record. Claims haven't risen at all in the past three weeks. While the rise we've seen so far looks like it would qualify as a recession, the net loss of jobs so far has not been as much as in past recessions. The jury is still out on whether this is a recession.

Weekly claims for unemployment have risen about as much as they did in the 2001 recession, and that was the mildest on record. Claims haven't risen at all in the past three weeks. While the rise we've seen so far looks like it would qualify as a recession, the net loss of jobs so far has not been as much as in past recessions. The jury is still out on whether this is a recession.

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

The dollar has seen its lows (2)

Everything is crashing, it seems, with the very important exception of the dollar, which is up 20% from its all-time low six months ago. The dollar is up against every currency in the world, with the only exception I'm aware of being the yen. Not coincidentally, the yen and the dollar were among the world's weakest currencies six months ago, and now they are both soaring.

Everything is crashing, it seems, with the very important exception of the dollar, which is up 20% from its all-time low six months ago. The dollar is up against every currency in the world, with the only exception I'm aware of being the yen. Not coincidentally, the yen and the dollar were among the world's weakest currencies six months ago, and now they are both soaring.So what does this mean? It's fashionable to talk about how the world is undergoing a massive deleveraging that is resulting in a severe asset price deflation. Real estate is down 20%, commodity prices are down 25%, gold is down 20%, oil is down 50%, and global stock markets are down 50%. It's a vicious cycle, the deflationists say, since falling prices only trigger more sales, and the end isn't yet in sight. That's the glass-half-empty explanation.

I prefer the glass-half-full interpretation. Of course there are many institutions and individuals who are being forced to deleverage, but prices aren't falling into the abyss, they are merely retreating from unsustainably high levels. Everything that is down today is still much higher than it was a few years ago (with the exception of US equities, which are revisiting their 2002 lows). And as the Spot Commodity chart shows, prices are still lofty when viewed from an historical perspective.

In short, the dollar is returning to more normal levels, as are the prices of things like real estate, gold, and energy. While this impoverishes those who bet that "things" would continue to rise in price while the dollar continued to fall, it enriches everyone else. The dollar's new-found strength is boosting the global purchasing power of US citizens, and making everyday living expenses more affordable.

In short, the dollar is returning to more normal levels, as are the prices of things like real estate, gold, and energy. While this impoverishes those who bet that "things" would continue to rise in price while the dollar continued to fall, it enriches everyone else. The dollar's new-found strength is boosting the global purchasing power of US citizens, and making everyday living expenses more affordable.The big story from 2002 until recently was that money was cheap (because the Fed was easy), and everyone started wanting less money and more things. So they borrowed or sold dollars and bought houses, gold, and other currencies. This resulted in a huge shift in relative prices which grew to be unsustainable. We're now reversing that binge. The big story today is that everyone wants more money and fewer things. So they are paying off loans and buying dollars, and selling houses, gold, and other currencies.

Just as the cycle maxed out when prices for things got ridiculously high, it ought to "min" out when prices get ridiculously low. Stocks and corporate bonds already look ridiculously low. As this last chart shows, at the rate we're going it won't be long before commodity prices reach the ridiculously low levels (in real terms) that we saw in the early 2000s.

Prices are changing to accommodate changing preferences. At some point they will stop adjusting and we'll reach a new equilibrium point. Meanwhile, the Fed is furiously accommodating the world's desire for more dollars, and that ought to mitigate the extent to which this cycle swings to the downside.

Prices are changing to accommodate changing preferences. At some point they will stop adjusting and we'll reach a new equilibrium point. Meanwhile, the Fed is furiously accommodating the world's desire for more dollars, and that ought to mitigate the extent to which this cycle swings to the downside.

Banks are lending by the bushel (3)

Just a reminder that the banking industry has not shut down, despite what you read in the MSM. This chart shows loans made by banks to small and medium sized companies. These now total $1.6 trillion and counting. In the past four years they have almost doubled. There is no shortage of money in the world: all measures of the US money supply are at or very near all-time highs. The problem continues to be a shortage of buyers. People continue to worry about the solvency of banks and other institutions that hold subprime mortgage-backed paper, because it is very difficult to analyze these securities. This will take time to sort out, and it may help when the Fed and Treasury start buying some of the stuff.

Just a reminder that the banking industry has not shut down, despite what you read in the MSM. This chart shows loans made by banks to small and medium sized companies. These now total $1.6 trillion and counting. In the past four years they have almost doubled. There is no shortage of money in the world: all measures of the US money supply are at or very near all-time highs. The problem continues to be a shortage of buyers. People continue to worry about the solvency of banks and other institutions that hold subprime mortgage-backed paper, because it is very difficult to analyze these securities. This will take time to sort out, and it may help when the Fed and Treasury start buying some of the stuff.

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Why I'm optimistic

For the benefit of new visitors, let me recap why I am optimistic.

To begin with, it's not hard to be optimistic when everyone is pessimistic and there is no shortage of bad news to worry about (e.g., Obama is likely to win, he wants to raise taxes and expand government; housing prices are plunging; financial markets are frozen; banks aren't lending; stock prices have collapsed; the great majority of economists are now saying we're in a recession, and the only areas of disagreement are over how deep and how long the recession will be). I think that the market has priced in all the bad news by now, and is fully expecting the news to get worse, which is why corporate bonds and stocks are so incredibly cheap.

All this would be reason alone to be optimistic, but here's the good news the pessimists are overlooking: 1) the Fed, along with other major central banks, has launched a massive effort to pump money into the banking system and backstop the credit worthiness and credibility of major financial institutions and money funds, and there are plenty of signs that these efforts are gaining traction—swap spreads and the TED spread have plunged, and implied option volatility is down; 2) there is plenty of money in the system, with all measures of money supply currently at all-time highs; 3) the credit squeeze is a myth—bank lending is at all-time highs and nonfinancial commercial paper is expanding—the problem is not a shortage of money but a shortage of buyers; 4) the credit default swap market has so far managed to settle and liquidate many hundreds of billions of contracts without so much as a hiccup, and without a shred of assistance or oversight from the federal government; 5) housing prices have plunged and this has resulted in a surge of home sales, to the point where buyers are competing with each other to grab foreclosed properties; 6) capital spending by corporations has been rising for the past year, laying the foundation for future productivity gains, 7) the labor market is weak but not collapsing—corporate layoffs according to Challenger Gray & Christmas have risen only modestly, the Monster Index appears to have leveled off, and weekly unemployment claims are flat for the past four weeks; and 8) speculative excesses have been wrung out of the commodity markets, leaving most prices (especially energy prices) at levels that pose little or no threat to future growth.

In short, we're seeing evidence that unprecedented action by central banks is restoring confidence, and there are lots of signs that the market is busy fixing itself. Rather than pulling the rug out from under the economy, the financial market has functioned as an ideal shock absorber for the real economy. This means that the recovery from this crisis could come much quicker than most would expect.

I've talked about all of this in previous posts. I called for a bottom in the equity market a few days too early, it seems, but the action of the past week or so, especially the improvement in key financial indicators such as swap spreads and the TED spread, has significantly increased my confidence that we've seen the worst of this financial crisis.

To begin with, it's not hard to be optimistic when everyone is pessimistic and there is no shortage of bad news to worry about (e.g., Obama is likely to win, he wants to raise taxes and expand government; housing prices are plunging; financial markets are frozen; banks aren't lending; stock prices have collapsed; the great majority of economists are now saying we're in a recession, and the only areas of disagreement are over how deep and how long the recession will be). I think that the market has priced in all the bad news by now, and is fully expecting the news to get worse, which is why corporate bonds and stocks are so incredibly cheap.

All this would be reason alone to be optimistic, but here's the good news the pessimists are overlooking: 1) the Fed, along with other major central banks, has launched a massive effort to pump money into the banking system and backstop the credit worthiness and credibility of major financial institutions and money funds, and there are plenty of signs that these efforts are gaining traction—swap spreads and the TED spread have plunged, and implied option volatility is down; 2) there is plenty of money in the system, with all measures of money supply currently at all-time highs; 3) the credit squeeze is a myth—bank lending is at all-time highs and nonfinancial commercial paper is expanding—the problem is not a shortage of money but a shortage of buyers; 4) the credit default swap market has so far managed to settle and liquidate many hundreds of billions of contracts without so much as a hiccup, and without a shred of assistance or oversight from the federal government; 5) housing prices have plunged and this has resulted in a surge of home sales, to the point where buyers are competing with each other to grab foreclosed properties; 6) capital spending by corporations has been rising for the past year, laying the foundation for future productivity gains, 7) the labor market is weak but not collapsing—corporate layoffs according to Challenger Gray & Christmas have risen only modestly, the Monster Index appears to have leveled off, and weekly unemployment claims are flat for the past four weeks; and 8) speculative excesses have been wrung out of the commodity markets, leaving most prices (especially energy prices) at levels that pose little or no threat to future growth.

In short, we're seeing evidence that unprecedented action by central banks is restoring confidence, and there are lots of signs that the market is busy fixing itself. Rather than pulling the rug out from under the economy, the financial market has functioned as an ideal shock absorber for the real economy. This means that the recovery from this crisis could come much quicker than most would expect.

I've talked about all of this in previous posts. I called for a bottom in the equity market a few days too early, it seems, but the action of the past week or so, especially the improvement in key financial indicators such as swap spreads and the TED spread, has significantly increased my confidence that we've seen the worst of this financial crisis.

Swap spreads point to a huge corporate bond rally

Swap spreads are the most basic and the most liquid of credit spreads. They tend to lead other spreads, with the best example being the 2001-2002 period, when swap spreads fell way in advance of other spreads. Swap spreads measure generic or systemic risk in the economy, while BAA spreads, for example, measure the risk of certain types of companies. So it's not unusual that swap spreads should move first. For example, the underlying economic conditions seem to be improving right now, but it may take us awhile to know whether ABC company is going to benefit.

Swap spreads are the most basic and the most liquid of credit spreads. They tend to lead other spreads, with the best example being the 2001-2002 period, when swap spreads fell way in advance of other spreads. Swap spreads measure generic or systemic risk in the economy, while BAA spreads, for example, measure the risk of certain types of companies. So it's not unusual that swap spreads should move first. For example, the underlying economic conditions seem to be improving right now, but it may take us awhile to know whether ABC company is going to benefit.There is a fairly dramatic healing process taking place right now, as evidenced by a plunge in the TED spread (now 263 bps, down from a high of 481), a plunge in 10-year swap spreads (now 40 bps, down from a high of 80), and a plunge in 2-year swap spreads (now 103 bps, down from 167). The implied volatility of options has also declined: the Merrill MOVE index is down to 192 from a recent high of 265, and the VIX index is down to 56 from a high of 81. All of these are measures of fear and systemic risk, and they show significant improvement which probably reflects a) the concerted efforts of the world's central banks to alleviate financial market stress, and b) the free market's own efforts to sort out its difficulties by writing down and absorbing losses.

With the financial markets breathing a major sigh of relief, the next shoe to drop should be a rise in the price of corporate bonds and equities. It's hard to know when that will take place, but corporate bond and equity prices still reflect an inordinate amount of fear and uncertainty. As the chart above shows, spreads on corporate bonds have skyrocketed to levels once thought to be impossible, and equity prices also reflect extremely pessimistic assumptions. But if swap spreads are reflecting some palpable improvement in the fundamentals, it only stands to reason that the outlook for individual companies will start to improve as well.

Monday, October 20, 2008

Are swaps forecasting a huge equity rally?

I've always been drawn to swap spreads as a leading indicator of other things (e.g., credit spreads, generic financial conditions, fear, health of the economy), so when I put together this chart I told myself to not get too excited, because it suggests that the big selloff in equity markets was just a temporary thing that will soon be almost entirely reversed. Wouldn't that be exciting?

I've always been drawn to swap spreads as a leading indicator of other things (e.g., credit spreads, generic financial conditions, fear, health of the economy), so when I put together this chart I told myself to not get too excited, because it suggests that the big selloff in equity markets was just a temporary thing that will soon be almost entirely reversed. Wouldn't that be exciting?

10-yr swap spreads have really turned the corner

Central banks are really gaining traction in their efforts to improve liquidity conditions. 10-year swap spreads are now lower than they have been at any time since the peak of the housing price bubble about three years ago. At 44 bps today, they are within spitting distance of the 30-40 bps range that we would expect in "normal" times. This tells me that the market is finally able to look out across the valley of the current crisis and see a future than looks much brighter. This is extremely good news.

Central banks are really gaining traction in their efforts to improve liquidity conditions. 10-year swap spreads are now lower than they have been at any time since the peak of the housing price bubble about three years ago. At 44 bps today, they are within spitting distance of the 30-40 bps range that we would expect in "normal" times. This tells me that the market is finally able to look out across the valley of the current crisis and see a future than looks much brighter. This is extremely good news.And all this good news comes amidst a general outpouring of angst over how deep and long the recession we are supposedly in is going to be. You have to be careful of getting your news on TV. That is, unless you watch Larry Kudlow.

Aussie dollar comes back to earth

Further to my previous post, here's the value of the Aussie dollar relative to my estimate of its purchasing power parity against the US dollar. Both the Aussie and the Canadian dollars are "commodity currencies" and they have both plunged pretty much in line with the big drop in commodity prices, only the Aussie dollar has fallen by more.

Further to my previous post, here's the value of the Aussie dollar relative to my estimate of its purchasing power parity against the US dollar. Both the Aussie and the Canadian dollars are "commodity currencies" and they have both plunged pretty much in line with the big drop in commodity prices, only the Aussie dollar has fallen by more.If you were thinking of leaving the US if Obama wins, Australian is now much more affordable. If my PPP estimate is correct, an American travelling in Australia should find that things cost about the same there as they do here. As recently as last July things probably cost about 40% more in Australia. This is good news also for those of us who like Australian wine.

Commodity bubble pops

The second chart shows the very strong correlation between the Canadian dollar and commodity prices. The first chart shows the value of the Canadian dollar in US dollars, relative to my estimate of what the purchasing power parity (green line) of the loonie is. Think of the green line as the "normal" rate of exchange, one that would put most US prices on a par with most Canadian prices.

Back in 2002-2003 the Canadian loonie was quite undervalued, and so were commodities. That was the tail end of the big deflationary squeeze the Fed put us through with its very tight monetary policy stance from 1995 through 2000. With dollars in short supply, the value of the dollar rose and commodity prices fell. US inflation also reached a significant low around that time.

Then came the Fed's easy money period, and that saw the dollar collapse and commodity prices soar. By March of this year the dollar had fallen to extraordinary levels, and commodities had reached stratospheric levels. Like the housing bubble, it couldn't last. Now we're seeing the frantic unwinding of commodity speculation and all the short dollar sales that made so much money for people in the past several years.

As the first chart suggests, the dollar is still weak (and the loonie is still strong relative to PPP), and by inference commodity prices are still strong, only much less so. We're rapidly approaching levels that are "normal" in an historic context. This has to be a very positive development. The collapse of commodity prices doesn't reflect a collapse of the global economy, but rather an unwinding of speculative excesses.

Spreads continue to narrow

Swap spreads have tightened across the board. The TED spread today is 316 bps, down about 150 bps from its recent all-time high. Spreads are still very high by historical standards, but the improvement in the past few weeks is extremely positive. This is a sign that the logjam in the fixed income market is breaking up. This is a good leading indicator for the health of financial markets in general, and is adding to the case that we've seen the worst.

Swap spreads have tightened across the board. The TED spread today is 316 bps, down about 150 bps from its recent all-time high. Spreads are still very high by historical standards, but the improvement in the past few weeks is extremely positive. This is a sign that the logjam in the fixed income market is breaking up. This is a good leading indicator for the health of financial markets in general, and is adding to the case that we've seen the worst.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Real estate prices are not in free-fall

Tonight I spoke with my nephew who does mortgage lending in the Inland Empire for a major bank (Southern California real estate that lies about 35-45 miles east of Los Angeles). He related something remarkable: Just the other day he was one of 15 buyers bidding on a home that his bank had foreclosed on and was selling at auction. The home last sold about 3-4 years ago for $780K. The bank was asking $400K, in addition to requesting that bids include a minimum down payment of 20%. My nephew’s job is to prequalify all those who want to bid. He hopes that if they have the winning bid they will finance the purchase with him. He says he is doing lots of business, which is why he wanted to bid on this house. It turns out that the minimum bid was $400K, exactly what the bank was asking, and the winning bid was $430K, with a 30% down payment! My nephew did not have the winning bid. He is going to have to be more aggressive the next time around.

Does this sound like a real estate market that is melting down? I don't think so. I think prices in many areas have fallen much more than the general public perceives, and these prices are attracting plenty of buyers. Therefore I think we are getting very close to the bottom in real estate prices.

Does this sound like a real estate market that is melting down? I don't think so. I think prices in many areas have fallen much more than the general public perceives, and these prices are attracting plenty of buyers. Therefore I think we are getting very close to the bottom in real estate prices.

Anna Schwartz bashes the Fed

Here's a must-read interview with renowned Fed scholar and historian Anna Schwartz. She blames the Fed for causing the crisis, and she thinks the Fed has been using the wrong tools to solve the crisis. And it's really good because she agrees with me: "This is not due to a lack of money available to lend, but to a lack of faith in the ability of borrowers to repay their debts." Other key excerpts:

So what does she suggest? The Fed and Treasury should be focusing on reducing the uncertainties that are blocking lending decisions, by letting banks fail, and by applying consistent policies when doing so. It would also help if the government can resolve the valuation problem of "toxic" securities, as Paulson is trying to do with his plan to buy these securities via auctions.

I would add that since the Fed caused this problem with too-easy money, then easing money even more is probably not a good thing to do. This could result in more inflation and more uncertainty going forward. Better to have confidence in the currency than to have too much currency.

I wish she had some magic solutions to the crisis which have been overlooked, but she doesn't, unfortunately. At least she is not afraid to tell us that the (Fed) Emperor has no clothes, and that throwing money at this crisis is not necessarily going to solve it.

(HT to Marc Denny)

"The Fed," she argues, "has gone about as if the problem is a shortage of liquidity. That is not the basic problem. The basic problem for the markets is that [uncertainty] that the balance sheets of financial firms are credible."

So even though the Fed has flooded the credit markets with cash, spreads haven't budged because banks don't know who is still solvent and who is not. Today, the banks have a problem on the asset side of their ledgers -- "all these exotic securities that the market does not know how to value."

How did we get into this mess in the first place? "The basic underlying propagator was too-easy monetary policy and too-low interest rates that induced ordinary people to say, well, it's so cheap to acquire whatever is the object of desire in an asset boom, and go ahead and acquire that object."

Today's crisis isn't a replay of the problem in the 1930s, but our central bankers have responded by using the tools they should have used then. They are fighting the last war. The result, she argues, has been failure. "I don't see that they've achieved what they should have been trying to achieve. So my verdict on this present Fed leadership is that they have not really done their job."

So what does she suggest? The Fed and Treasury should be focusing on reducing the uncertainties that are blocking lending decisions, by letting banks fail, and by applying consistent policies when doing so. It would also help if the government can resolve the valuation problem of "toxic" securities, as Paulson is trying to do with his plan to buy these securities via auctions.

I would add that since the Fed caused this problem with too-easy money, then easing money even more is probably not a good thing to do. This could result in more inflation and more uncertainty going forward. Better to have confidence in the currency than to have too much currency.

I wish she had some magic solutions to the crisis which have been overlooked, but she doesn't, unfortunately. At least she is not afraid to tell us that the (Fed) Emperor has no clothes, and that throwing money at this crisis is not necessarily going to solve it.

(HT to Marc Denny)

Friday, October 17, 2008

Best reason to vote for McCain -- divided government

All those who find Obama's promise of "Change" resonating deep inside them should "make sure" (Obama's favorite phrase) to read today's lead op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, "A Liberal Supermajority."

An Obama victory would give the Democrats control of the presidency and both houses of Congress. Obama, Nancy Pelosi, and Harry Reid would be running the show for at least the next two years. The last time we had a 3D government (Carter's 4 years, and Clinton's first 2 years) it ended badly for the Democrats, since it ushered in the Reagan presidency and handed Congress over to the Republicans in 1994.

Imagine if Obama were able to achieve his heart's desire, such as universal health care, increased regulation of business and financial markets, expansion of union power, higher taxes, government power to regulate CO2 emissions (a key priority according to Obama's energy advisor Jason Grumet would be to declare CO2 a dangerous pollutant, thus giving the EPA authority to set emission limits on power plants and manufacturers), and revival of the Fairness Doctrine, to name just a few. Is this the sort of change that you had in mind?

If it isn't, you should vote for McCain, even if it means holding your nose. A divided government would surely mean less expansion of government power and more room for the economy to fix its own problems.

An Obama victory would give the Democrats control of the presidency and both houses of Congress. Obama, Nancy Pelosi, and Harry Reid would be running the show for at least the next two years. The last time we had a 3D government (Carter's 4 years, and Clinton's first 2 years) it ended badly for the Democrats, since it ushered in the Reagan presidency and handed Congress over to the Republicans in 1994.

Imagine if Obama were able to achieve his heart's desire, such as universal health care, increased regulation of business and financial markets, expansion of union power, higher taxes, government power to regulate CO2 emissions (a key priority according to Obama's energy advisor Jason Grumet would be to declare CO2 a dangerous pollutant, thus giving the EPA authority to set emission limits on power plants and manufacturers), and revival of the Fairness Doctrine, to name just a few. Is this the sort of change that you had in mind?

If it isn't, you should vote for McCain, even if it means holding your nose. A divided government would surely mean less expansion of government power and more room for the economy to fix its own problems.

Money is plentiful (2)

Wow, the Fed really means business. According to data released yesterday, in the past few weeks the Fed has pumped about $132 billion worth of high-powered reserves into the banking system. As a result, bank reserves, which must back up a fraction of the deposits and checking accounts held by our banking system, have increased by a staggering 135%. If most of those extra reserves were not sitting idle because banks are trying to shore up their balance sheets, they could support such a massive expansion of the money supply (e.g., by allowing banks to make new loans) that it would make Bernanke's analogy of dropping money out of helicopters in order to fight deflation seem tame by comparison.

Wow, the Fed really means business. According to data released yesterday, in the past few weeks the Fed has pumped about $132 billion worth of high-powered reserves into the banking system. As a result, bank reserves, which must back up a fraction of the deposits and checking accounts held by our banking system, have increased by a staggering 135%. If most of those extra reserves were not sitting idle because banks are trying to shore up their balance sheets, they could support such a massive expansion of the money supply (e.g., by allowing banks to make new loans) that it would make Bernanke's analogy of dropping money out of helicopters in order to fight deflation seem tame by comparison.This is so far beyond any precedent that it's pointless to wonder what it might mean. It's enough, however, to know that the Fed is deadly serious in its fight to keep the banking system afloat. I've learned over the years that you can never underestimate the Fed's ability to achieve its objectives. After all, it has a monopoly on controlling and creating the world's reserve currency.

Housing starts have collapsed -- good news