I'm a monetarist when it comes to inflation. As Milton Friedman taught us, inflation is what happens when the supply of money exceeds the demand for it. The best measure of the supply of money is M2, but nowhere is there a statistic which directly measures the demand for money. Money demand can only be measured after the fact, by observing changes in the money supply and changes in inflation. For example, if inflation rises we can be sure that the demand for money has been less than the supply of money. Even if M2 growth is low, inflation can rise if the demand for money is falling. And as we saw in late 2020, rapid M2 growth can occur even as inflation remains low, because back then the demand for money was very strong given all the uncertainties and shutdowns. (Check out this post from October 2020 for more background on this.)

The Covid era has given us something akin to a laboratory experiment in the interaction between money supply and money demand. We've seen a massive, unprecedented increase in the money supply followed by an equally impressive decline in the money supply. Meanwhile, inflation has gone from low to high and is now halfway back to normal. The lags between money and inflation have been "long and variable," as Friedman noted. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve has paid virtually no attention to any of this, and neither has the press nor the vast majority of economists. There are lessons to be learned here, and fortunately, there is reason to remain optimistic about the future.

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of M2 (blue line) and its 6% per annum trend growth rate (green line) which has been in place since 1995. According to data released yesterday, M2 increased by $131 billion in May, breaking a 9-month losing streak totaling just over $1 trillion. M2 has fallen 4% in the past 12 months, and is up only 0.9% in the past 24 months. Yet M2 is still about $2.6 trillion above where it might have been in the absence of the Covid crisis. I've argued that this "extra" amount of M2 serves as a cushion against recession, because it means that the economy is still flush with cash and liquidity. See this post for more on why liquidity is so important to both the economy and financial markets.

Chart #2

Chart #2 compares the growth rate of M2 to the 12-month running total of the federal deficit. This strongly suggests that the $6 trillion of federal deficit spending in 2020-2022 was financed by money creation. The one good thing here is that the increased deficit over the past year has not resulted in any increase in M2, because the spending has been financed by borrowing, not money creation. This is as it should be. Bottom line: the source of the inflation surge in recent years has dried up, and inflation is on the way out.

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares the growth of M2 with the rate of CPI inflation lagged by one year. The chart suggests that there is approximately a one-year lag between changes in money supply growth and changes in inflation. Given the dramatic decline in M2 growth which began early last year, the chart suggests we will see a similar decline in inflation over the next 6 months or so. As I've argued for months, the decline in inflation is well underway.

Chart #4

Chart #4 is my attempt to quantify "money demand." I'm one of the few economists who pay attention to money demand because it's crucially important: after all, inflation is what happens when the supply of money exceeds the demand for money. Check out this post from October 2020, in which I elaborate on how strong demand for money can offset rapid growth in money supply. Money supply can be abundant, as it was in 2020, but inflation didn't show up until April of 2021. I think that's because the demand for money was very strong in 2020: everyone was hoarding money because of all the Covid-related uncertainty. Inflation began to appear in 2021 only after confidence picked up and life began returning to normal after the first round of vaccines—people no longer wanted to accumulate money. People began spending the money they had accumulated, and that aggravated the problem of supply-chain disruptions, driving prices higher. This post from March 2021 elaborates on these thoughts.

Think of the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP as the amount of cash and cash equivalents that the average person is willing to hold, expressed as a percent of their annual income. As the chart shows, money demand fell rather dramatically beginning in late 2021, and inflation peaked about six months later. In recent months the decline in money demand has slowed quite a bit; I think that's due to 1) the Silicon Valley Bank failure and 2) rising real interest rates. People are more cautious about holding money these days, and it's not a coincidence that most of the M2 increase in May was due to a $76 billion increase in retail money market funds which are now yielding almost 5%. Holding money when rates are 5% is a lot more attractive than when they were almost zero back in early 2022. Higher interest rates also discourage borrowing, especially for mortgages; mortgage originations have fallen by 50% in the past year. (Note: being less willing to borrow money is equivalent to being more willing to hold money.)

For the past 18 months the Fed has been raising short-term interest rates in an attempt to bolster the demand for money. If they hadn't done that, plunging money demand would have pushed prices even higher. In effect, they were trying to prevent the public from rapidly spending all the excess money that accumulated in the 2020-2021 period. And it has worked. The May pickup in M2 suggests there has indeed been a slowing in the decline in money demand.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows nominal and real yields on 5-yr Treasuries (red and blue lines), and the difference between the two (green line), which is effectively the market's expectation for what the CPI will average over the next 5 years. Inflation expectations today are about 2.1%, which is very close to what inflation averaged in the 20 years leading up to the 2020 Covid crisis. In effect, the bond market believes the inflation problem has been solved. The yield curve is very inverted these days (i.e., short-term rates are much higher than long-term rates), which means that the bond market expects the Fed to lower short-term interest rates dramatically over the next year or two—because the market believes the Fed will eventually realize that the inflation problem has been solved.

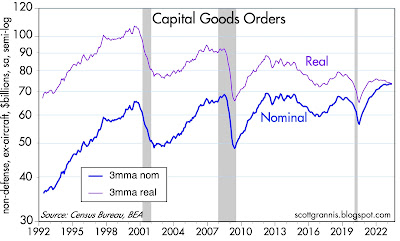

Chart #6

Changing the subject: Chart #6 shows the 3-mo. moving average of capital goods orders in both nominal and real terms. Capital goods orders ("capex") are investments that companies make which will boost future productivity (i.e., purchases of machinery, computers, tools, new plants). As such, capex is a leading indicator of future economic growth. Nominal capex has reached a new high in nominal terms, but in real terms capex has been lackluster to say the least: it's fallen almost 30% in the past two decades. I believe this tells us that economic growth in coming years will also be lackluster: 2% or less per year.

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows Bloomberg's index of financial conditions, with the components listed at the bottom. According to this, the outlook for financial markets and thus the economy is "normal."

Summary: There is nothing to fear from the behavior of M2; money and liquidity are still abundant and key indicators such as swap and credit spreads tell us that the economy's fundamentals are still sound. The source of our inflation problem has dried up and inflation is on its way back to normal. The Fed was slow to react to all this, but they have not yet made a significant mistake. It's therefore not surprising that the stock market has been creeping higher.