Forgive me if I'm a bit late with this top-down analysis of last February's faux-Stimulus Bill (aka The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009), but I have been worrying a lot of late about the gargantuan deficits that are being projected not only by the White House but also by the Congressional Budget Office.

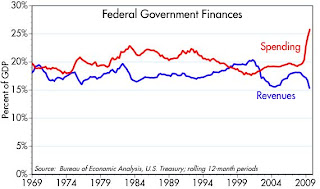

Forgive me if I'm a bit late with this top-down analysis of last February's faux-Stimulus Bill (aka The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009), but I have been worrying a lot of late about the gargantuan deficits that are being projected not only by the White House but also by the Congressional Budget Office.As I detailed in an earlier post, they are talking about 10-year deficits of about $10 trillion dollars, and you've got to believe they're putting all the positive spin on the numbers that they possibly can. Plus, no one is yet talking about what would happen to the numbers if healthcare reform or cap-and-trade passes. Some folks (e.g., The Concord Coalition) are saying the 10-year deficit could be $14 trillion or more. If the deficit is anything even close to $10 trillion over the next decade, this puts us in largely uncharted waters, since it would represent the biggest deficit, in both nominal terms and relative to GDP since World War II. Deficits could range from 6-10% of GDP annually, far out of the range of anything we've seen in the post-war period.

So I began asking myself some tough questions, especially since I've been saying that the economy can grow 3-4% a years in spite of the ugly fiscal policy environment staring us in the face. Just how easily are these deficits going to be financed? Could they effectively absorb all or most of the savings of the private sector, leaving the economy with little or no private-sector investment? Could this be the real "crowding-out" of private borrowers that became a fashionable concern during the Reagan years but in the end proved overblown? How can the economy grow if the government—a chronically inefficient spender and investor—is commandeering nearly all the economy's savings? Annual deficits on the order of 10% of GDP are reminiscent of Japan in recent decades, and haven't they led to a moribund economy and a crippled stock market?

As a supply-sider I have learned that deficits aren't necessarily bad things. Art Laffer years ago taught me that if the government is faced with a shortfall of revenues, of the two alternatives to plugging the gap—higher taxes or increased borrowing—taxpayers should always prefer the latter, since that gives them at least some hope of getting their money back in the future. If taxes rise, however, then the money is lost forever. Milton Friedman taught us that the burden of government is best measured not by the level of taxes or the deficit, but by the level of spending, since the government uses the economy's resources less efficiently than the private sector.

But these trillion-dollar deficits for as far as the eye can see are being driven primarily by a big increase in goverment spending. So that leaves us with the worst of all worlds, doesn't it? How can one be optimistic in the face of this impending disaster?

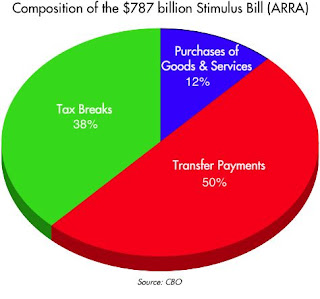

My former colleague at Western Asset, Mike Bazdarich, helped me come to terms with this apparent dilemma, by reminding me that most of the additional spending we're talking about is not really new spending. To illustrate this, the Stimulus Bill can be broken down as shown in the pie chart above. (Data based on the CBO's analysis of the bill.) As should be quickly apparent, only a very small part of the spending involves government purchases of goods and services. This is the part that will commandeer the resources of the private sector inefficiently. As Mike noted in a paper last March, of the $88 billion in federal purchases of goods and services, "only about $12 billion will be spent in the current fiscal year, with only an additional $26 billion slated to be spent in 2010." So we're really talking small potatoes here.

The vast bulk of the "spending" will just amount to reshuffling the distribution of income: $377 billion will be "spent" on transfers to state and local governments and individuals, and $284 bilion will be "spent" on tax breaks to individuals and corporations. Excerpts from Mike's paper:

From my supply-side perspective, 88% of the stimulus bill (transfers and tax breaks) will amount to taking money from one person and giving it to another, while only 12% (spending on goods and services) will involve new government spending that absorbs (inefficiently) resources from the private sector. And I should add that as of not too long ago, transfer payments (e.g., social security, medicare, unemployment insurance, welfare, subsidies) already accounted for over half of total federal spending. These transfer payments don't show up in the GDP accounts because they are not direct government payments for goods and services.

In analyzing the spending initiatives in the 2009 stimulus plan, it is important to distinguish between direct purchases of goods and services by the government and transfer payments to individuals, firms or state/local governments. Increases in purchases—procurement, hiring and the like—directly boost aggregate spending. Transfer payments merely disburse funds to recipients, where they may or may not be spent. Transfers are little different in effect from tax rebates (but with incentive effects reversed), and as the transfers in the stimulus package are also one-time payments, their prospective impact on spending is similarly small.

The bulk of these transfer payments will go to state/local governments in response to the fiscal emergencies these governments are experiencing. The best this aid can do will be to prevent declines in state/local government spending. Even those prevented declines would occur only if other financing sources were utterly unavailable. If other financing avenues were available to the local governments, then the aid would merely substitute federal debt for the state and local indebted- ness that would otherwise be incurred, with no net impact on GDP at all.

The story is much the same with about $100 billion of transfer payments to persons over the next two years. These are also one-time boosts and will likely elicit only slight changes in spending behavior, mostly affecting destitute households that would have no recourse to other financing sources without the temporary aid provided in the bill.

Transfer payments are awful things, of course, since they can and do create perverse incentives. Taking money from Peter who makes a lot and giving it to Paul who either doesn't earn much or doesn't work much is likely to result in Peter working less, while giving Paul an incentive to work less. That's a lose-lose proposition, but it's not going to shut down the economy. It's simply going to result in a slower-growing economy than we might otherwise have enjoyed. Keynesian economists fail to appreciate this, however, since they think that demand drives growth, whereas supply-siders insist that work and investment drive growth.

Almost all of the tax breaks in the stimulus bill are of the rebate variety, and that makes them not too unlike a transfer payment, since one group of taxpayers is favored with a reduced tax bill while another group will have to shoulder the burden of higher taxes in the future. The rebates are one-time, not permanent, and as such they won't do much to change behavior on the margin. Plus, a lot of the tax "rebate" money will go to those who haven't paid any taxes to begin with, so if anything, a windfall tax check could result in them working less. As supply-side theory emphasizes, the only tax cuts that can make a difference to the outlook for the economy are those that result in a positive change in behavior on the margin. Cutting the income or corporate tax would directly increase the after-tax incentive to work and invest, and likely result in more work and a faster-growing economy. Unfortunately, the stimulus bill makes no permanent cuts to income or corporate tax rates.

If I had to restate the above in economic jargon, I would be saying that the "multipliers" used by the White House and the CBO are way too high. Instead of boosting economic growth by a percentage point or two per year on average, the net effect of the bill's spending will be to reduce economic growth by one or two percentage points per year compared to what it otherwise might have been.

So, think about the trillion-dollar deficits mainly in terms of transfer payments. The government is not really going to be consuming a trillion extra dollars of the economy's resources every year that might otherwise be put to better use by the private sector. The wasteful spending is likely to be only a fraction of a trillion per year. There's still some room for private saving and investment, albeit less. Again, this is not going to kill the economy, but it is likely to slow it down.

I've always thought Obama was a socialist at heart, and he has made it very clear that income redistribution is high on his list of priorities. As these numbers show, that is exactly what he has achieved with his stimulus bill. If he manages to get universal healthcare and cap-and-trade passed, then the redistribution will be even larger and more intrusive, while wasting some additional portion of the economy's resources in the process. It's all very unfortunate from a supply-side perspective, but it's not the end of the world.

Look on the bright side: to the extent that Obama's policies lead to positive change on the margin, it will be by increasing the opposition to his policies and subtracting from the Democrats' majority in Congress in next year's elections. And that, in turn, creates more favorable conditions for positive policy changes on the margin in the future.