Valued readers, please excuse me. For the past few months I've suffered from writer's block complicated by a lack of government-produced data. I now have some facts to work with, and they look pretty good. I've assembled a baker's dozen of my favorite charts here, and I will try to keep the commentary lean and let the charts do the heavy lifting. It feels a lot like Christmas!

To sum up: The economy is in decent shape (2-3% growth) and inflation remains subdued (2.5% or less). More specifically, the M2 money supply is growing at a very moderate 4.5% rate and most if not all of the $6 trillion increase in M2 that was "printed" during the Covid era has been absorbed. There is still no evidence that Trump's tariffs have boosted inflation. The main source of slightly-above-target inflation in recent years can be traced to the government's faulty measurement of housing and shelter costs, and these have finally subsided and should remain low (if not negative) for the foreseeable future.

Commodity prices (abstracting from gold, which appears to inhabit an alternative universe) are very well behaved, and haven't shown any meaningful increase for years. GDP growth was surprisingly strong in Q3/25, and Trump's Big Beautiful tax cuts, coupled with impressive deregulation and an actual shrinkage of the public sector workforce, have set the stage for continuing growth in the coming year. It is comforting to see a 4-5% increase in business investment so far this year (e.g., capital goods orders and shipments), and it is now common knowledge that AI is already contributing to improved productivity. Finally, it is also VERY comforting to see that federal government spending has not increased at all over the past 12 months, while revenues have surged by almost 10%!

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of the M2 money supply, arguably the best measure of readily-spendable money. It grew at a 6% pace from 1995 through 2007, during which time inflation averaged about 2%. Then all hell broke lose: M2 surged by some $6 trillion in a 2-yr period, fueled by Covid stimulus spending which was effectively monetized. That bulge now has all but disappeared.

Chart #2 shows the 6-mo. annualized growth rate of M2, now a mere 4.6%. The economy is now on a low-inflation monetary diet. As I have said about M2 many times in the past 5 years, this is arguably the biggest news that no one, not even the Fed, is paying attention to.

Chart #3 shows the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP. I call this the "demand for money," since it essentially measures how much of our annual incomes we prefer to hold in the form of money. Money demand surged in the first year or so of Covid, because people were terrified and largely unable or unwilling to spend all the cash the government was doling out. Strong money demand effectively neutralized the surge in the M2 money supply, which explains why inflation didn't start rising for a year after M2 began to soar. Money demand then collapsed beginning in mid-2022, as things began to return to normal, and that effectively offset the collapse and actual shrinkage of M2—that's why a contracting money supply didn't cause the recession that was so widely anticipated. (Remember: inflation happens only when the supply of money exceeds the demand to hold it.) Now money demand is almost all the way back to where it was prior to Covid.

Chart #4

Chart #5

Chart #4 compares the strength or weakness of the dollar to the level of inflation-adjusted spot commodity prices, while Chart #5 shows the nominal level of those same commodities since early 2020. These are all very basic commodities, not the sort that are subject to speculative pressures (like gold can be). What we see here is a very strong inverse correlation between the dollar and real commodity prices. A stronger dollar tends to coincide with weaker commodity prices, and vice versa. Note that commodity prices over the past 33 years haven't changed at all in real terms, and the dollar has only strengthened modestly. Over the past several years, commodity prices have gone nowhere—a strong symptom of an absence of underlying inflationary pressures.

Chart #6 is structured the same way as Chart #4, except that I've used the inflation-adjusted price of crude oil. In real terms, oil prices are relatively low, and that reinforces the outlook for low and stable inflation. Oil is the most volatile of all commodity prices, and the price of energy is an important contributor to the economy's health. Nationwide gasoline prices are currently just under $3 per gallon, and that is roughly what gasoline prices have averaged over the past 20 years. This is very good news for economic growth.

Chart #7

Chart #7 looks at the short-term, annualized rate of change in Owner's Equivalent Rent, which in turn constitutes about one-third of the CPI. In the past two months, this important component of the CPI has decelerated markedly; this will subtract meaningfully from reported inflation over the next 10 months.

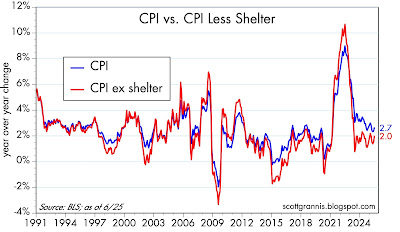

Chart #8

Chart #8 compares the year over year change in the total CPI to its ex-shelter version. The gap between the red and blue lines over the past 2 years is largely due to the government over-estimating shelter costs. The gap has now all but closed.

Chart #9

Chart #9 shows the long-term growth trend of real GDP (green line), which averaged about 3.1% per from the post-war period through 2007. Sadly, the economy has yet to return to those glory days; growth has averaged only a bit more than 2.3% per year since the Great Recession ended in 2009. Why this huge shortfall? I suspect a variety of culprits: massive increases in transfer payments (e.g., green energy subsidies, Obamacare), burdensome regulations (e.g., CAFE standards), and DEI hiring, to name a few. Stepping back, mankind has spent several trillions of dollars on inefficient energy projects in a vain attempt to "save" the planet from climate change. A return to efficient energy investment appears already to be underway. This is great news for the planet and its economies.

Chart #10

Chart #10 tracks the growth of private sector jobs in recent years, which are now growing at a snail's pace. Contrast this to the surprisingly strong growth of Q3/25 GDP (4.3%) and you must conclude that productivity is on the rise by more than enough to offset the drag of massive deportations of illegals. Meanwhile, federal government payrolls have shrunk by 9% (273K) so far this year! To my mind that's the equivalent of pouring much less sand into the wheels of commerce.

Chart #11

Chart #11 shows the inflation-adjusted price of gold over the past 113 years. Monetarists like me have trouble reconciling soaring gold prices with an apparent absence of inflation pressures. Central banks have meaningfully increased their purchases of gold in the past four years, and that at least partially explains gold's rise to levels never before seen—or even imagined. On the other hand, this could be a classic case of speculative froth which eventually exhausts itself and collapses. The 30% collapse in Bitcoin prices since early October could be a harbinger of trouble ahead for other markets.

Chart #12

Chart #12 paints a disturbing picture, suggesting that the recent collapse in bitcoin could be presaging a similar decline in equity prices. The market cap of crypto currencies peaked at $4.28 trillion on October 6th, and current stands at $2.95 trillion; $1.33 trillion of paper wealth has thus evaporated in a matter of weeks. Dabble in gold and bitcoin at your peril. I wouldn't touch the stuff—give me real, productive assets instead.

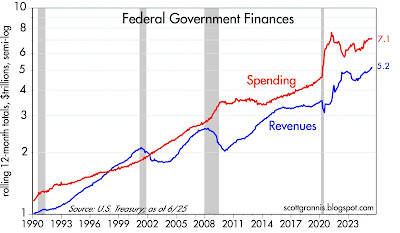

Chart #13

Chart #13, in contrast, paints a hopeful picture; federal government finances look to be returning to some measure of sanity. Federal government spending has been flat for the past year, while revenues have increased by 10%. The days of $2 trillion dollar annual deficits are fading fast. Federal debt owed to the public has been 90-100% of GDP for over 5 years (it peaked at 103% in mid-2020) and may soon begin to decline. In the meantime, the true burden of our national debt is currently 3.7% of GDP, and that is significantly less than the 4.5-5% levels which prevailed during the 1980s. There is still reason to be optimistic.

Happy New Year!

P.S. Thanks to Larry K for the words of encouragement!