Here are 5 charts which illustrate some very important points about the state of the economy and the outlook for inflation.

The economy is doing "Ok", but it's nothing to write home about. The housing sector is struggling mightily, and is very unlikely to improve without a boost from lower interest rates. Jobs growth is modest at best, and unlikely to improve without immigration reform which prioritizes making hard-working illegals legal instead of deportable.

There is no longer any doubt that the Fed has tamed inflation.

Given low inflation and an economy that is struggling, there is no reason for the Fed to delay lowering interest rates. Trump is right to criticize Chairman Powell for this, but Trump could help by backing off on his egregious tariff demands and his aggressive deportations of illegals, most of whom are decent, hard-working, and tax-paying members of society. He should focus instead on lowering tax and regulatory burdens and greatly expanding immigration quotas.

Given low inflation and an economy that is struggling, there is no reason for the Fed to delay lowering interest rates. Trump is right to criticize Chairman Powell for this, but Trump could help by backing off on his egregious tariff demands and his aggressive deportations of illegals, most of whom are decent, hard-working, and tax-paying members of society. He should focus instead on lowering tax and regulatory burdens and greatly expanding immigration quotas.

Chart #1

Chart #1 is yet another update of a chart I've been featuring for the past 15 years. The green line represents the 3.1% annual growth path the economy followed from 1966 through 2007. During that time, the economy was able to rebound and regain that growth path after every recession (this is commonly referred to as the "plucked string" theory of growth). Since the end of the Great Recession in mid-2009, the economy has only managed to follow a 2.3% annual growth path (red line). If the economy had instead recovered to a 3.1% growth path it would be 23% bigger today. I've attributed this monstruous growth shortfall to increased tax and regulatory burdens and a sizable increase in transfer payments. (See my post from 11 years ago which explains this in greater detail.)

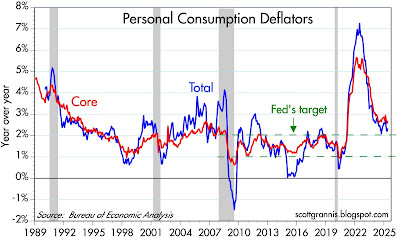

Chart #2

Chart #2 compares the year over year growth rate of private sector jobs (red line) with the year over year growth rate of real GDP (blue line). It stands to reason that without more people working it's hard for the economy to expand. Currently, jobs growth is only slightly higher than 1%, and the economy has expanded by only 2% in the past year. That 1% difference is a good approximation of productivity growth, which is less than the 1.9% annualized rate of productivity since 1966. If jobs growth doesn't pick up (and it won't if we are deporting millions of hard-working illegals), then the economy is going to continue to grow at a sluggish pace.

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares the level of housing starts (blue line) to an index of homebuilders' sentiment (red line). There is only one interpretation: the outlook for the housing market is gloomy. Housing affordability is at all-time lows (due to the combination of high prices and high interest rates), and the inventory of unsold homes is relatively high and rising rapidly. I'm hearing talk that construction sites around Southern California are having trouble getting workers to show up—they are mostly Mexican and many are likely illegally here. Everyone is afraid of ICE raids.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows the year over year change in the Personal Consumption Deflators (total and core). Although both are somewhat above the Fed's target range, a closer looks says they are well within it. In the past three months (March, April, and May), the annualized rate of growth of both these inflation measures has plunged to 1.1% (total), and 1.7% (core). Powell's favorite measure, PCE core services less shelter, is up at a mere 1.1% annualized pace in the past 3 months. Note: these same three months include the impact of Trump's higher tariffs—which is to say that higher tariffs have not resulted in higher inflation by any measure. This is what I and many others predicted.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows the three components of the PCE deflator: services, durable goods, and non-durable goods. As should be obvious, goods prices have been flat to down for the past 3 years. Inflation is only to be found in the services sector, and shelter costs make up a large portion of that sector. Lower housing costs are going to be depressing services inflation for a long time. The Case/Shiller index of national home prices peaked earlier this year and has fallen at an annualized rate of 1.8% in the most recent 3 months. Add it all up and the outlook for inflation is LOW for the foreseeable future. I think the Fed is getting very close to realizing this, so we will soon have lower interest rates and that should help.

Despite this somewhat downbeat, near-term outlook, I remain reasonably confident that we can avoid a disaster and the economy can improve with time. Trump has been a wrecking ball in many ways, which is unfortunate, but in the process he has provoked a lot of thought and shaken up things that needed to be shaken up (corruption and waste in the federal government, immigration, trade barriers, to name just a few). Between the Abraham Accords and the targeted bombing of Iran's nuclear sites, he may well have transformed the future of the Middle East for the better.