A little over 3 weeks ago I opined that the the big October decline in US equity prices still looked like a

panic attack. Shortly thereafter, equity prices climbed over 6%, but have once again returned to their late-October lows. I haven't made further comments because I didn't see that anything had changed. I'll comment now, but it still looks like a panic attack. Key economic and financial fundamentals remain healthy, but fear still dominates the landscape. One new development is the very recent 24% plunge in AAPL, driven by fears that demand for new iPhones is much weaker than previously thought. This has led many observers to theorize that global demand in general may be flagging, increasing the risk of a global recession that might spread to the US. To be sure, equity markets in Europe and Japan have dropped around 10% since late-October, but Chinese equities, surprisingly, have actually picked up a bit of late. It's not an easy diagnosis, but a global or even a US-only recession is far from an inevitable conclusion.

What follows is a recap of the same charts I featured October 29th, plus a few extras:

Chart #1

As Chart #1 shows, market selloffs are typically accompanied by a rise in the market's fear and uncertainty. (The ratio I use to capture that is the Vix index divided by the 10-yr Treasury yield. The former is a direct measure of fear and also a measure of how expensive options are, while the latter is a proxy for the market's confidence in the outlook for the economy; higher yields typically reflect more confidence, while lower yields reflect uncertainty about the future.) It's worth noting that the "worry" level these days is significantly less than it has been at other times in the past several years, even though the market's response has been of similar magnitude.

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows the level of 2-yr swap spreads in the US and in the Eurozone. Swap spreads are excellent coincident and leading indicators of systemic risk and financial market liquidity. At today's levels, swap spreads tell us that liquidity in the US is abundant and systemic risk is low. The Eurozone isn't quite as healthy, however, since it struggles with Brexit and the Italian budget outlook, among other things such as generally sluggish growth.

Chart #3

Chart #4

Chart #3 shows the level of real and nominal 5-yr Treasury yields and the difference between the two, which is the market's expected annual inflation rate over the next 5 years. Inflation expectations today are very close to the Fed's 2% target. They have dipped a bit in the past week or so, and Chart #4 suggests that the reason is simply a sharp drop in oil prices. We have seen this pattern quite a few times in recent years. Today's 1.8% forward-looking inflation expectation is nothing to worry about. Indeed, it tells the Fed that there is no pressing need to tighten monetary policy, and that should be a source of comfort to the market. Indeed, in the past two weeks the bond market has priced out one Fed tightening, and now expects only two rate hikes (from 2.25% currently to 2.75%) by the end of next year, with no more rate hikes after that.

I note that gold has been flat for the past 5 years, and the dollar is only 4% above its 5-yr average. Neither suggest that the Fed today is too tight or too loose. The Fed is not likely the main source of the market's concerns.

Chart #5

Chart #5 compares the value of the dollar, relative to other major currencies, to an index of industrial metals prices. Note that there is tendency for these two variables to move inversely—a stronger dollar tends to coincide with weaker commodity prices and vice versa. The "gap" between the dollar's current level, which is on the strong side, and commodity prices, which are still relatively strong, suggests that the global economy is still healthy (i.e., demand for commodities is still relatively strong despite the relatively strong dollar). This runs directly counter to the current meme which holds that the global economy is slowing down meaningfully.

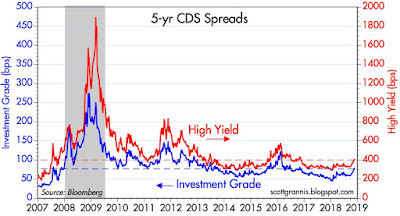

Chart #6

Chart #6 shows 5-yr Credit Default Swap Spreads. These are highly liquid and generic indicators of the market's confidence in the outlook for corporate profits—wider spreads equate to more concern, tighter spreads to less concern. These spreads have increased somewhat as equities have experienced a sharp correction. But they are still relatively low from an historical perspective. This further suggests the market is still reasonably confident in the outlook for corporate profits and the health of the economy, despite all the concerns floating around.

Chart #7

Chart #8

Charts #7 and #8 show various measures of corporate credit spreads. Spreads in the energy sector have been hit the worst, due to the recent decline in oil prices, but the damage is nothing compared to what happened when oil prices collapsed from $110/bbl in mid-2014 to $30/bbl in early 2016. The recent decline has brought oil prices back to where they were a year ago. This is not a major problem.

Chart #9

Chart #10

Chart #9 shows Bloomberg's measure of the S&P 500's PE ratio, which uses trailing 12-month profits from continuing operations. Since January of this year PE ratios have plunged rom 23.3 to now 18.1 (-22%). This reflects a rather sudden loss of confidence in the long-term outlook, especially considering that profits continue to rise, and are in fact up 22% versus November 2017, as Chart #10 shows. Curiously, the bond market appears to be much more confident about the future than the stock market (given that credit spreads are up only modestly, whereas equities have suffered a significant correction). This further suggests the equity market may just be in the throes of a panic attack. Looked at from the positive side, the recent decline in PE ratios has made the market that much more attractive.

Chart #11

Chart #11 shows the equity premium of the S&P 500 relative to the 10-yr Treasury yield. The current earnings yield of the S&P 500 is 5.5%, whereas the current 10-yr Treasury yield is only 3.1%. That investors are apparently indifferent to an equity yield that is more than 200 bps higher than the risk-free yield on Treasuries suggests that the market doesn't have much confidence in the outlook for earnings.

Risk aversion has been an important part of the market's behavior in the current business cycle expansion, and it hasn't gone away even as economic growth has picked up of late. Consider how optimistic the market was back in the 1980s, when the equity risk premium was solidly negative for many years. It's been solidly positive for most if not all of the current expansion. Selling equities in favor of bonds today means giving up yield, so sellers must have the courage of their convictions.

Chart #12

Chart #12 compares the real Fed funds rate (a good measure of how loose or tight monetary policy is) with the slope of the Treasury yield curve. Recessions have always been preceded by a substantial tightening of monetary policy and a flattening or inversion of the yield curve. We're a long way from those two conditions today. Neither of these variables have changed meaningfully since late October. Real short-term yields are still very low, and the yield curves still positively-sloped.

Chart #13

Chart #14

Chart #13 compares the value of the Chinese yuan with the level of China's foreign exchange reserves. The yuan rose relentlessly from 1994 to 2013, despite the central bank's repeated interventions (i.e., buying dollars and selling yuan) to keep it from strengthening even further. But since then the yuan has been under pressure, and the central bank has had to sell foreign currency (any buy yuan) to keep it from declining further. This represents a sea change in the outlook for the Chinese economy. Before 2014 it was a magnet for capital, whereas now capital is fleeing the country. Still, capital flight has not been severe; the central bank has "lost" only about $1 trillion of its once $4 trillion in forex reserves.

As Chart #14 shows, the real value of the yuan vis a vis the world's currencies is still much stronger than it was throughout most of China's modern past. But on the margin it has been weak for several years now, and China's economic growth rate has slowed from 12% in 2010 to now only 6.5%. The bloom is off the Chinese rose, and if recent trends continue, China's economy could prove to be the world's weakest link.

Chart #15

Chart #15 shows how incredibly weak the Chinese equity market has been relative to the US equity market since China first entered the developed-country world in 1995. Chinese equities have suffered significantly more this year than any other developed countries' equity markets. This once again makes the point that China is the country that is hurting the most. If China doesn't find a way to deal with President Trump, what's bad for China could prove to be bad for everyone. I continue to believe that a deal is possible, since it would be in everyone's best interests to have lower tariffs and more respect for international property rights.

Chart #16

Chart #16 compares the US and Eurozone equity markets. The US has been outperforming Europe for the past decade, and to a sizable degree.

The global winds are at our back, but that doesn't mean we can ignore local headwinds. The following charts highlight some areas of weakness in the US economy that bear watching.

Chart #17

As Chart #17 shows, there has been a remarkable tendency for the physical volume of goods transported by US trucks and the level of the S&P 500 stock index. As the economy grows, so do equity prices. Truck tonnage was weak in the third quarter, and that appeared to foreshadow the October-November weakness in the stock market. But the latest reading of the Truck Tonnage index shows a significant 2.2% increase. On the surface, this would suggest that the economy is entering the boom phase that supply-siders have been looking for ever since Trump's impressive reduction in corporate tax rates. But it's also possible that trucks these days are scurrying around trying to deliver a flood of imports that were purchased in the hopes of avoiding increased tariffs scheduled for January.

Chart #18

Chart #18 shows the real and nominal level of capital goods orders, which in turn are a good proxy for business investment. By this measure business investment has increased by an impressive 16% since the November 2016 election. But investment has gone relatively flat in recent months, and it is far from impressive by historical standards. This could and should be better. What are companies doing with all their new-found profits? Buybacks are one answer, but they are still only a fraction of the current market value of US equities and thus not a satisfying answer.

Chart #19

Finally, Chart #19 shows how the wind has been knocked out of the residential construction industry in recent months. Most disturbing is the big decline in homebuilders' sentiment last month. We know that rising prices and higher mortgage rates have made housing much less affordable. But the current level of new housing starts is still far below its 2006 peak, and still below the level required to replace aging structures and accommodate new families. I've argued that this adds up to a pause or consolidation, not the beginning of another crash. Why can't prices stop rising or decline a bit, without that leading to the wholesale collapse of everything like what we saw in 2006-2008? Why can't the relatively strong economy continue to boost incomes and drive demand for more housing? Household leverage today is far below the levels that preceded the Great Recession, and mortgages are not being extended on ridiculous terms as they were back then. Still, it remains the case that what's bad for housing tends to be bad for the economy.

The horizon is not empty of threats, but the worst one (China) can be avoided or seriously mitigated by a trade "deal" that is in everyone's best interests. Free trade is a wondrous tonic for global growth, and free trade benefits all parties, contrary to what Trump's clueless Peter Navarro happens to think. All we need is for clearer heads to prevail. How hard is that?