Friday, October 28, 2016

Can we have a Mulligan?

I think it's time we all realized that the only solution to our presidential election problem is to agree to give ourselves a mulligan. Let's just start this whole thing over from scratch.

The $3 trillion gap

Today we got the first estimate of third quarter GDP. The economy advanced at a 2.9% annualized pace, much better than the 1.1% annualized pace for the first half of the year. But it remains the case that the economy appears to have downshifted from the 4+% pace we saw in the second and third quarters of 2014; growth over the past year has been a miserable 1.5%. I think this has a lot to do with the tremendous amount of uncertainty surrounding the upcoming elections. People in charge of making big decisions are holding off to see if things are likely to improve next year—or deteriorate. Business investment remains quite weak, and the pace of job growth has slowed. The combination of years of bad policies (e.g., rising tax and regulatory burdens, income redistribution) coupled with uncertainty about the future equals a huge cost in lost output, which could be as much as $3 trillion this year alone.

The chart above illustrates just how miserable economic growth has been in the current recovery. Instead of averaging just over 3% growth per year, as it did from 1965 though 2007, the economy has only managed a 2.1% annualized pace for the past 7 ¼ years. The gap between where we are and where we might have been had this been a normal recovery is a bit more than $3 trillion, by my calculations. That's huge, and that's the measure of our discontent.

An economy can't grow if businesses don't invest. As the chart above shows, capital goods orders—the seed corn of future productivity gains—have been flat to down for the past 5 years.

The chart above tells the same story from a different perspective. Fixed private investment has been much weaker in the current cycle than it was in prior cycles.

Businesses have been making huge profits during the current expansion (see chart above), but not investing nearly as much as they could have. If we want a stronger economy we need to find ways to encourage businesses to invest more. Lower taxes—especially the onerous tax on overseas profits—could do the trick, and so would reduced regulatory burdens. Corporations have parked some $3 trillion overseas that could be brought back if tax burdens were sharply lower.

The chart above illustrates just how miserable economic growth has been in the current recovery. Instead of averaging just over 3% growth per year, as it did from 1965 though 2007, the economy has only managed a 2.1% annualized pace for the past 7 ¼ years. The gap between where we are and where we might have been had this been a normal recovery is a bit more than $3 trillion, by my calculations. That's huge, and that's the measure of our discontent.

An economy can't grow if businesses don't invest. As the chart above shows, capital goods orders—the seed corn of future productivity gains—have been flat to down for the past 5 years.

The chart above tells the same story from a different perspective. Fixed private investment has been much weaker in the current cycle than it was in prior cycles.

Businesses have been making huge profits during the current expansion (see chart above), but not investing nearly as much as they could have. If we want a stronger economy we need to find ways to encourage businesses to invest more. Lower taxes—especially the onerous tax on overseas profits—could do the trick, and so would reduced regulatory burdens. Corporations have parked some $3 trillion overseas that could be brought back if tax burdens were sharply lower.

As the chart above shows, private sector jobs growth has slipped to a 1.5% pace over the past six months. With weak jobs growth and virtually no productivity gains, the economy is simply not going to be able to do much better than 1.5-2% going forward.

Not surprisingly, the bond market has figured this out. As the chart above shows, the real yield on 5-yr TIPS is -0.3%, and that is consistent with expectations that economic growth will be stuck at around 2% or so for the foreseeable future.

The problem with Hillary—leaving aside for the moment things like the mounting evidence of corruption and influence peddling surrounding the Clinton Foundation thanks to her careless handling of her email server—is that she does not understand the importance of incentives to economic growth and prosperity (and neither did Obama). Trump does. For all his flaws, he would be much more likely to pursue policies that could close our $3 trillion gap. Can we afford to not give him a chance? We'll find out soon.

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

The biggest scandals: debt, corruption and healthcare

In his recent column for USA Today, Glenn Reynolds correctly notes that instead of sex and behavior scandals, the electorate should be talking about the monumental scandals that have impacted the entire country. He lists a variety of corruption scandals (not exhaustive, since among others he omits the IRS scandal which is still ongoing), and reminds us that Obama's signature achievement, healthcare reform, is collapsing, after rejiggering one seventh of the US economy and causing wrenching adjustments and huge costs for nearly everyone in the process. Unfortunately, he neglects to put numbers on the debt scandal, so allow me to pitch in:

Shortly after Obama assumed office in early 2009, our national debt (debt held by the public) stood at $6.8 trillion. By the end of this year it will have reached about $14.3 trillion, having more than doubled in the space of just eight years.

A $7.5 trillion increase in our national debt in eight years is a huge number, but so is the economy, which will likely be almost $19 trillion in size by the end of this year. Only by comparing the debt to the size of the economy can we judge how big and burdensome the debt really is. By my calculations, federal debt should be about 76% of GDP by the end of this year. In the history of our country, the surge in our debt burden that began in 2008 (Bush gets a share of the blame) is exceeded only by the immense amount of debt we incurred while fighting WW II.

I should point out that the federal deficit this year will likely exceed 3% of GDP. Fortunately, that is down hugely from a peak of 10.2% in 2009. Unfortunately, the deficit is once again increasing relative to GDP, having bottomed at 2.2% of GDP a year ago.

The chart above illustrates the change in our national debt burden by presidents. Red bars stand for increasing debt burdens, green bars for declining debt burdens. The increase in our debt burden under Obama is about the same as the net increase in our debt burden for all presidents preceding Nixon. Clinton stands out for having achieved the most significant reduction in our debt burden since the 1970s, and G.W. Bush stands out for reversing all of that gain.

When as a nation we borrow money to finance our federal debt, what matters most is not how much we borrow, but what we do with the money we have borrowed. (Recall Milton Friedman's admonitions that "spending is taxation." All money spent must eventually be paid for by taxes, either directly or indirectly, even if it's financed initially by debt.) Debt that is used to finance productive investments can pay for itself by boosting incomes and creating new jobs (e.g., infrastructure, research). But debt that is used to finance consumption is money that is squandered—Greece comes to mind as a good example of what not to do with borrowed money.

Shortly after Obama assumed office in early 2009, our national debt (debt held by the public) stood at $6.8 trillion. By the end of this year it will have reached about $14.3 trillion, having more than doubled in the space of just eight years.

A $7.5 trillion increase in our national debt in eight years is a huge number, but so is the economy, which will likely be almost $19 trillion in size by the end of this year. Only by comparing the debt to the size of the economy can we judge how big and burdensome the debt really is. By my calculations, federal debt should be about 76% of GDP by the end of this year. In the history of our country, the surge in our debt burden that began in 2008 (Bush gets a share of the blame) is exceeded only by the immense amount of debt we incurred while fighting WW II.

I should point out that the federal deficit this year will likely exceed 3% of GDP. Fortunately, that is down hugely from a peak of 10.2% in 2009. Unfortunately, the deficit is once again increasing relative to GDP, having bottomed at 2.2% of GDP a year ago.

The chart above illustrates the change in our national debt burden by presidents. Red bars stand for increasing debt burdens, green bars for declining debt burdens. The increase in our debt burden under Obama is about the same as the net increase in our debt burden for all presidents preceding Nixon. Clinton stands out for having achieved the most significant reduction in our debt burden since the 1970s, and G.W. Bush stands out for reversing all of that gain.

When as a nation we borrow money to finance our federal debt, what matters most is not how much we borrow, but what we do with the money we have borrowed. (Recall Milton Friedman's admonitions that "spending is taxation." All money spent must eventually be paid for by taxes, either directly or indirectly, even if it's financed initially by debt.) Debt that is used to finance productive investments can pay for itself by boosting incomes and creating new jobs (e.g., infrastructure, research). But debt that is used to finance consumption is money that is squandered—Greece comes to mind as a good example of what not to do with borrowed money.

By that measure, we have squandered a huge portion of the money we've borrowed in the past 8+ years. For example: Since the end of 2007, transfer payments have increased by $3.76 trillion, rising from 12% of GDP to now 15% of GDP. This is money that was taken from one person and given to another, with no regard as to whether the beneficiary has contributed anything to the economy. Call it "unproductive spending" if you will. And as I noted some years ago, only 8% of the nearly $1 trillion in "stimulus" spending under Obama was spent on transportation and infrastructure. Not a dime went to increase anyone's incentive to work harder or invest more.

We've been spending lots of money in an unproductive fashion, and that helps explain why this has been the weakest recovery ever. As bad as things are, however, this is not necessarily the end of the world. We can reverse course, and with a lot of growth we can reverse the increase in our debt burden, which is what happened in the post-war period. Unfortunately, Hillary will almost certainly attempt to double-down on the failed spending and taxation policies of the Obama administration. Only Trump is talking about pro-growth policies, with the notable exception of his complete lack of understanding of the dynamics of trade.

Housing as an inflation hedge

Over long periods, the inflation-adjusted price of homes in the U.S. has tended to increase by a little more than 1% per year. However, this doesn't mean that owning a home is a good way to make a 1% real return on your money.

According to the Census Bureau, new homes have been getting bigger and bigger: since 1973, the average new house increased from 1660 square feet to 2687 square feet, for an annualized increase of 1.15%. New homes today are 1,000 square feet larger than they were in 1973, and living space per person has nearly doubled. Bigger and better houses explain why inflation-adjusted home prices have increased by a little more than 1% per year. On balance, and over long periods, homes maintain their value, relative to other goods and services. They are a thus a decent inflation hedge, nothing more.

The first of the charts above shows indices of real and nominal national home prices since 1987, according to Case Shiller. Over that period, the annualized real rate of increase in home prices was 1.4%, only slightly faster than the long-term increase in the size of homes. The second of the the charts above shows real existing single-family home prices since 1968; its annualized increase is about 1.1% per year, very much in line with the increasing size and quality of homes.

In short, housing has been a decent inflation hedge, holding its value over long periods.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

15 important charts

The craziest, most depressing election in my lifetime is less than three weeks away. Half of the country will be shocked, dismayed and depressed at the outcome, whoever happens to win. One candidate is an uncouth, xenophobic buffoon, the other a congenital liar who is deeply corrupted. The policies they are proposing, if implemented, could spark an international trade war, another recession, an economic boom, or pave the way for another four years of miserably slow growth. Meanwhile, the Middle East is in terrible shape, ISIS is attacking within our borders, Russia and China are making threatening advances, and North Korea is lobbing missiles our way while testing nuclear weapons.

With so much uncertainty out there, you would expect to see markets trading at depressed levels. Many pundits, however, argue that the world's central banks are inflating asset prices by keeping interest rates artificially low. Which is it?

As I examine the facts, as summarized in the 15 charts that follow, I find little or no evidence of distorted prices, looming deflation, or another recession in the making. I see more signs of caution and risk aversion than signs of exuberance. My contrarian instincts warn me that it's unwise to expect the trends of the past seven years—slow growth and low inflation—to continue indefinitely, yet that seems to be what the market is priced to. How to proceed?

Investors face an excruciating dilemma, which can be measured by the extremely low level of short-term interest rates—even below zero in Europe and Japan—versus the much higher level of yields on risky assets. If you can't stand the risks, of which there are many, you must pay a very high price for the safety of cash and cash equivalents. In many developed economies, yields on cash and cash equivalents are meaningfully negative in real terms: even cash is risky these days!

This first chart is arguably the most important. What it shows is that the world's demand for money (using M2—currency, retail money market funds, time deposits, checking accounts and bank savings deposits—as a proxy) has soared in unprecedented fashion since 2008. The world wants to hold more cash relative to nominal GDP than ever before. People everywhere are more risk averse; caution permeates our daily lives; uncertainty abounds. People worry about QE, about the risk of another financial collapse, about the direction of politics, about the rise of terrorism, about instability in the Middle East, about the proliferation of nuclear weapons; there is no shortage of things to worry about.

Another way to interpret this first chart is to see that it was the public's increasing demand for money that essentially forced the Fed to adopt Quantitative Easing. The Fed needed to increase the supply of money in order to satisfy the world's huge demand for money. Otherwise we would have experienced deflation, which is what happens when there is a shortage of money.

The two charts above tell the inflation story. Headline inflation in the U.S. has been very low and even negative in the past few years, but that's entirely due to the plunge in oil prices. As the top chart shows, the ex-energy version of the CPI has been running at a 2% rate for the past 14 years. As the bottom chart shows, headline inflation, which reached negative levels last year, is now reversing and will likely return to 2% or higher shortly (all it would take is three more months of increases like the 0.29% increase we saw last month). It's very similar to what happened during the 1986-1988 period, when oil prices suffered a collapse and recovery of similar magnitude to what we've seen since mid-2014. The bond market already understands this: Based on the pricing of TIPS and Treasuries, the market expects CPI inflation to average between 1.6 and 1.9% per year over the next 10 years, which is very close to what we've seen over the previous 10 years.

One other important message here: since inflation has been relatively low and stable in the U.S. for a number of years, we can infer that the Fed has done a good job of balancing the supply of money with the demand for money. QE has not been inflationary. Although it might become inflationary should the public's demand for money start to decline and should the Fed fail to take timely, remedial action. That's an important and lingering source of uncertainty.

For all the talk about how oil is "cheap," the chart above shows that in real terms, today's oil prices are just about average from a long-term perspective. The chart above also shows that nearly every recession in the past 45 years has followed or coincided with a spike in real oil prices. Although oil prices have bounced significantly from their recent January lows, the operative trend that is impacting the economy is still one of cheaper prices: oil today is some 50% cheaper than it was in the 2011-2014 period. Oil prices, in other words, do not pose a threat to growth—more likely, they are supportive of growth.

I've long argued that swap spreads are excellent indicators of systemic risk and financial market health. When swap spreads are 40 bps or less, it's a sign that financial markets are liquid and systemic risk is very low. (See a longer explanation for the meaning of swap spreads here.) U.S. 2-yr swap spreads are just about perfect at current levels. Eurozone spreads are trading at the high end of what might be termed a "normal" range, but that probably reflects the fact that conditions in Europe are not as stable as they are here. In any event, swap spreads today are far less than what they have been during times of great economic stress and anxiety. Today's level of swap spreads is symptomatic of healthy liquidity conditions and an economy with relatively low systemic risk, and that adds up to a bulwark against recession.

I should further note that any Fed "tightening" in the current environment of huge excess bank reserves is not going to put the banking system under any significant degree of stress. The Fed used to tighten by reducing the supply of reserves, but this time around they will tighten simply by increasing the interest they pay on bank reserves. Liquidity is going to be abundant even as interest rates rise, and that should mitigate recession risk.

The chart above is a reminder that swap spreads are often good leading indicators of other credit spreads, and of the health of the economy. (Note how swap spreads rose in advance of the past two recessions and fell in advance of recoveries.) Earlier this year, when swap spreads were low but high-yield spreads were high because of concerns that cheap oil would bankrupt the oil patch, I argued that healthy financial market conditions would allow the economy and the markets to adjust to the oil price shock without disrupting the economy. That appears to have been the case.

Corporate credit spreads, shown in the chart above, have declined quite a bit from their recent and past spikes, but they are still meaningfully above their historical lows. The message: markets are still cautious, because investors demand a somewhat-higher-than-normal risk premium for accepting the credit risk of corporate bonds.

As the chart above shows, the current PE ratio of the stock market is above average. This is not unprecedented, however, and we have seen much higher PE ratios in the past, although not on a sustained basis.

One problem with standard PE ratios is the way they are measured, typically by dividing current prices by profits over a trailing 12-month period. However, standard measures of earnings that conform to FASB accounting standards are not necessarily the same as "economic" profits. The chart above corrects for both these problems by dividing current prices by the most recent quarter's estimate of economic profits found in the National Income and Product Accounts. (HT to Art Laffer for pioneering this approach back in the 1980s.) Here we see that PE ratios today are only marginally higher than their long-term average. Considering how low interest rates and discount rates have been and continue to be, does it not make sense for PE ratios to be at least somewhat above average?

See here for a more detailed discussion of PE ratios and NIPA profits.

The chart above is a relatively arcane way of measuring whether stocks are "cheap" or "expensive." The Rule of 20 says that stocks are fairly valued when the sum of PE ratios and the year over year change in the Core PCE deflator equals 20. On this basis, stocks are somewhat expensive, but still nowhere near their past extremes.

The chart above shows the difference between the earnings yield on stocks (the inverse of PE ratios) and the yield on 10-yr Treasuries. It's been higher at times, but not often. Put another way, consider the difference between the PE ratio of the 10-yr Treasury today (i.e., 57, the inverse of its 1.75% yield), and the PE ratio of the S&P 500, which is just over 20. Investors today are willing to pay $57 for a dollar's worth of annual earnings on T-bonds, but only 20 or so for a dollar's worth of corporate earnings. Wow. If this isn't risk aversion I don't know what is. In effect, the market is saying that it is extremely unlikely for corporate profits to maintain their current levels for the foreseeable future.

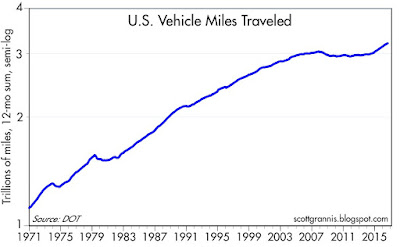

The chart above illustrates one tangible result of lower oil prices: people are driving more, after roughly 10 years of no increase at all. Prices do make a difference in people's behavior. Consider: if today's oil price has boosted the public's willingness and ability to use their vehicles, might it not also boost the economy's ability to grow?

As I've noted before, Chemical Activity has been picking up of late, and that is a good sign that industrial production is about to pick up, after almost three years of zero growth in manufacturing activity.

In the chart above, we see that the real yield on 5-yr TIPS tends to track the real growth rate of the economy. That makes sense, because the risk-free real yield on TIPS needs to compete with the ability of investors to achieve real returns in the broader economy. For years now, real yields have been trading at depressed levels and the economy has turned in its worst recovery ever. The current relatively low and stable level of real yields suggests the market holds out little or no hope for any meaningful improvement in economic activity in the foreseeable future.

The market fully expects the Fed to raise short-term interest rates, probably by 25 bps at the December FOMC meeting, and perhaps once more sometime next year. But even at 1%, the real funds rate would be zero or negative, and the yield curve won't become flat or negative until the market realizes that the Fed has tightened so much that its next move is likely to be to cut rates. Thus, tight monetary policy is still years in the future, barring an unexpected surge in economic growth and/or a surprising rise in inflation, either of which would force the Fed to become more aggressive.

– – – – –

Investors need to weigh all these considerations against their own appetite for risk. Personally, and despite all the negatives looming on the horizon, I don't find a compelling reason to exit risky assets. Going to cash is not without risk, and the extra yield available on risk assets is meaningful—and it compounds fruitfully over the years. If I saw evidence of widespread optimism in the market I might reconsider, but so far I see more caution than optimism, and that is encouraging from a contrarian point of view. Having said that, the current environment does not present a compelling opportunity to put one's financial future at serious risk.

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

Chart updates

The outlook hasn't changed much this month, and I've been doing some traveling (this week I'm in Park City to attend a Cato conference), so that explains the lack of posts. What follows are some updated charts and commentary:

The September payroll report was consistent with what I've been saying in recent months: jobs growth has downshifted, from a 2% annual pace to now 1.7% or so. That's not a huge deal, but I think it reflects the uncertainty surrounding the elections and the eventual policy outcome. Those with investment decisions to make on the margin are most likely to hold off until next year before deciding to move ahead with new investment/expansion/hiring plans. We therefore are unlikely to see any meaningful improvement in the economy this year.

Jobs growth is slowing, but the growth of the labor force is picking up. More and more people are deciding they would prefer to work than to sit on the sidelines. The gap between the two lines in the above chart suggests that there are as many as 10 million people potentially available to re-enter the workforce.

There is a similar gap between the current size of the economy and its potential size, as the chart above shows. That gap is now equivalent to about $3 trillion in "lost" income per year. In other words, there is tremendous untapped potential in the U.S. economy. That potential could be tapped if policies become more growth-friendly (e.g., lower tax rates, reduced regulatory burdens). That's what this election should be about, but the degree of acrimony that exists between the two parties and their candidates is an unfortunate distraction. I wish I knew how it will all play out.

The unemployment rate has stopped declining and looks set to increase a bit in coming months. Traditionally, a rising unemployment rate only happens as the economy slides into a recession. Things are very different this time around, however. The unemployment rate is moving higher not because more and more people are getting laid off, but because more and more people are deciding they'd rather work than sit on the sidelines. This is arguably the first time this has happened in modern times. Don't be worried, therefore, by a rising unemployment rate—it doesn't mean what it used to mean.

In the currency market, the big news is the abrupt decline of the pound. According to my PPP analysis, the pound is now "cheap" relative to the dollar, for the first time in more than a decade. Time to make plans to visit the U.K.! The most likely cause of the pound's weakness is the U.K.'s decision to exit the European Union. There are lots of things in play, and thus the outcome is fraught with uncertainty. In the long run I think a Brexit is good for the U.K. (since it will free up markets), but in the near term the uncertainty is not surprisingly bad for markets.

The U.S. stock market is more nervous these days, as indicated by the Vix index in recent months rising from a low of 11.3 to now about 16. But the Vix/10-yr ratio hasn't increased much at all, because 10-yr yields have risen from a low of 1.36% to now about 1.8%. Investors are more nervous, but yields are rising because there is less pessimism surrounding the outlook for growth. As a result, the stock market has been relatively stable.

In the chart above we see that the prices of 5-yr TIPS and gold have been flat to down in recent months. This suggests that the market's demand for safe-have assets has stabilized or declined, and that further suggests that the general level of uncertainty has improved a bit. Nothing wrong here.

UPDATE: Here is a chart of excess reserves (reserves held by banks that are not needed to collateralize deposits). Excess reserves have declined in line with a decline in total reserves; apparently the Fed is slowly (and quietly) unwinding some of its QE efforts. But there are still plenty of reserves out there.

The September payroll report was consistent with what I've been saying in recent months: jobs growth has downshifted, from a 2% annual pace to now 1.7% or so. That's not a huge deal, but I think it reflects the uncertainty surrounding the elections and the eventual policy outcome. Those with investment decisions to make on the margin are most likely to hold off until next year before deciding to move ahead with new investment/expansion/hiring plans. We therefore are unlikely to see any meaningful improvement in the economy this year.

Jobs growth is slowing, but the growth of the labor force is picking up. More and more people are deciding they would prefer to work than to sit on the sidelines. The gap between the two lines in the above chart suggests that there are as many as 10 million people potentially available to re-enter the workforce.

There is a similar gap between the current size of the economy and its potential size, as the chart above shows. That gap is now equivalent to about $3 trillion in "lost" income per year. In other words, there is tremendous untapped potential in the U.S. economy. That potential could be tapped if policies become more growth-friendly (e.g., lower tax rates, reduced regulatory burdens). That's what this election should be about, but the degree of acrimony that exists between the two parties and their candidates is an unfortunate distraction. I wish I knew how it will all play out.

The unemployment rate has stopped declining and looks set to increase a bit in coming months. Traditionally, a rising unemployment rate only happens as the economy slides into a recession. Things are very different this time around, however. The unemployment rate is moving higher not because more and more people are getting laid off, but because more and more people are deciding they'd rather work than sit on the sidelines. This is arguably the first time this has happened in modern times. Don't be worried, therefore, by a rising unemployment rate—it doesn't mean what it used to mean.

In the currency market, the big news is the abrupt decline of the pound. According to my PPP analysis, the pound is now "cheap" relative to the dollar, for the first time in more than a decade. Time to make plans to visit the U.K.! The most likely cause of the pound's weakness is the U.K.'s decision to exit the European Union. There are lots of things in play, and thus the outcome is fraught with uncertainty. In the long run I think a Brexit is good for the U.K. (since it will free up markets), but in the near term the uncertainty is not surprisingly bad for markets.

The U.S. stock market is more nervous these days, as indicated by the Vix index in recent months rising from a low of 11.3 to now about 16. But the Vix/10-yr ratio hasn't increased much at all, because 10-yr yields have risen from a low of 1.36% to now about 1.8%. Investors are more nervous, but yields are rising because there is less pessimism surrounding the outlook for growth. As a result, the stock market has been relatively stable.

The Fed is on the minds of nearly everyone these days, but I don't see major problems ahead. The chart above tells us that the market only expects a very modest rise in real short-term interest rates in coming years. (That's the message of the blue line in the chart above.) And that makes sense given the sluggish economy and the relatively low and stable rate of inflation. Things could change in the future, of course, but interest rates are likely to surprise on the upside only if the economy strengthens meaningfully and/or inflation rises.

It's important to keep in mind that there are two ways the Fed can "tighten" monetary policy: 1) they can take steps that result in an increase in the nominal Fed funds rate, and/or 2) they can take steps that result in an increase in the real Fed funds rate. It's the change in the real Fed funds rate that is the most important, since that affects real borrowing costs (and real returns on savings) for everyone. Traditionally, the Fed has increased the nominal funds rate by draining bank reserves, which the Fed accomplishes by selling bonds that it owns. Prior to late 2008, any reduction in the supply of bank reserves would force banks to curtail their lending, since banks had a strong incentive to avoid holding excess reserves. With a shortage of reserves, banks were forced to pay up to borrow needed reserves (needed to collateralize their deposits), and that is what caused short-term interest rates to rise.

Since 2008 that has all changed, for the first time ever. Today there are over $2 trillion in excess reserves in the banking system. As a practical matter, the Fed can't possibly drain enough reserves on the margin to cause a shortage of reserves. Instead, in order to push short-term rates higher all the Fed has to do today is declare that it will pay more interest on the reserves held by the banking system.

So as the current "tightening" cycle proceeds, the banking system will almost certainly not experience any shortage of reserves or any shortage of essential liquidity. Today, higher short-term rates will mean only that borrowing costs increase marginally and the rewards to savings increases marginally. It's more of a zero-sum game now, whereas "tightening" in prior cycles meant the banking system was being squeezed and money and liquidity were becoming scarce. Of course, we've never experienced a tightening cycle under the current IOER regime, so it's impossible to predict how things will play out. But it is safe to say that this time things will be different. The Fed won't really be tightening in the sense of limiting bank liquidity; rather, it will acting directly to raise the level of short-term interest rates. A quarter-point increase in short-term borrowing costs and a similar increase in the interest rate paid on bank savings deposits and money market funds is not likely to create more than a minor ripple in the U.S. economy. Lots of people (e.g. savers) will likely cheer, while few (borrowers) will grumble. As long as liquidity is plentiful, the banking system and the financial markets will be able to play the role of "financial shock-absorber," and that in turn will mitigate the risk of recession.

In the chart above we see that the prices of 5-yr TIPS and gold have been flat to down in recent months. This suggests that the market's demand for safe-have assets has stabilized or declined, and that further suggests that the general level of uncertainty has improved a bit. Nothing wrong here.

UPDATE: Here is a chart of excess reserves (reserves held by banks that are not needed to collateralize deposits). Excess reserves have declined in line with a decline in total reserves; apparently the Fed is slowly (and quietly) unwinding some of its QE efforts. But there are still plenty of reserves out there.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)