A much stronger-than-expected manufacturing report (54.5 vs. 52) from the Institute for Supply Management, indicating that U.S. manufacturing activity in July was picking up, has proved once again that the perceived health of the economy is a more powerful determinant of interest rates than the Fed's monthly purchases of $85 worth of Treasuries and MBS. 10-yr Treasury yields are now over 100 bps higher than they were when the Fed initiated its QE3 campaign almost a year ago—in which time it has purchased enough bonds to finance the entire federal deficit—because the market now sees that the economy is on a stronger footing, even though expectations for growth remain very unimpressive. A year ago the market thought the U.S. economy faced a serious risk of many years of dismal growth or even another recession; today the market likely believes that the economy can sustain growth of 2-3%, a rate of growth that would still qualify this recovery as being the weakest ever.

This is a very important assertion, since it casts serious doubt on the assumption that many observers have made that the Fed has been artificially lowering interest rates and in the process distorting the capital markets and artificially stimulating the economy. As I've asserted for a long time, the Fed's QE program has been designed not to stimulate the economy but to accommodate the world's intense demand for money and cash equivalents. And not only has monetary policy not been stimulative, but fiscal policy has been acting like a headwind to growth, since its emphasis has been on redistribution, huge new regulatory burdens (e.g., Dodd-Frank, Obamacare), and higher taxes. In short, what we are seeing is that the economy has been growing in spite of monetary and fiscal policy, not because of it. The recovery, as meager as it has been, is nevertheless a genuine recovery which could be much stronger if fiscal policy were to get out of the way of the private sector. Which it in fact is, though much remains to be done for the outlook to brighten significantly.

The export orders subcomponent of the ISM index suggests that overseas economies continue to expand. If the world is increasing its purchases of U.S. goods, that helps sustain our growth.

The prices paid index continues to point to little or no inflationary pressures, confirming that monetary policy has not been stimulative—it's simply been accommodative of strong demand for money.

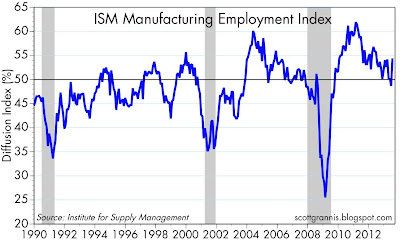

The employment index last quarter had dipped to zero-growth levels, but has now rebounded, suggesting that manufacturers feel more optimistic about the future.

Although the Eurozone has yet to pull out of its two-year recession, manufacturing activity is no longer contracting, as suggested by the July Markit survey of manufacturing. It would appear from this chart that both the U.S. and the Eurozone are enjoying a modicum of improving conditions.

1 comment:

Well...central bankers have been fighting the war against inflation since the 1970s, and they mostly won that war.

Global sovereign interest rates have been falling for decades, and now are converging on ZLB. Japan was a leader in this regard.

Japan tried passive central banking in ZLB for the better part of 20 years. It did not work.

Since Abenomics, the Nikkei Dow is up 70 percent. They are showing 4 percent GDP growth. I like prosperity. I like QE.

Since QE started in the USA, the DJIA has nearly doubled.

In this climate of dead inflation and capital gluts, a passive central bank means keeping the monetary noose around the economy's neck nice and tight.

For better or worse, we have three choices:

1. Go back to higher rates of inflation, in the 3-6 percent range, and then "conventional" central banking can be effective.

2. Do nothing and mimic Japan. BTW, you will suffer 80 percent declines in real estate and equities.

Or 3. Keep very low inflation and interest rates in a era of capital gluts, and use QE as a permanent conventional tool.

You know, I loved the 1970s, and disco and a full head of hair. But the 1970s are over.

Inflation is dead, capital is abundant even glutted. ZLB is the new norm in much of the developed world.

We need central banking for the 2010s, not the 1970s.

Post a Comment