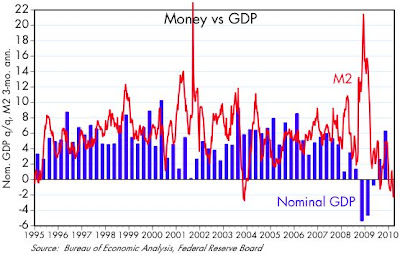

This is a follow-up to my post last month on the same subject. The issue is that M2 money growth has been extremely slow in the past year, as the first chart shows.

As this chart also illustrates, the big slowdown in money growth has coincided almost exactly with the big rise in equity prices. I don't think this is a coincidence. Indeed, I think it is a story that makes perfect sense. This past recession was provoked by an extreme increase in the demand for money, which was expressed in a huge increase in money balances as people cut back their spending and did just about everything they could to increase their money balances. Now that the fear of an international banking collapse has passed, and evidence accumulates that the US and global economies are firmly in recovery mode, the public's desire to accumulate money has gone in reverse. Money is being spent that was hoarded, and money balances are declining.

Declining demand for money has reduced the growth rate of M2, but it has not slowed the economy because declining money demand means that money is being spent at a faster rate, and that is lifting nominal GDP. The next chart illustrates this point quite nicely, as we see that extreme swings in M2 growth tend to coincide with equally strong, but opposite, swings in nominal GDP growth.

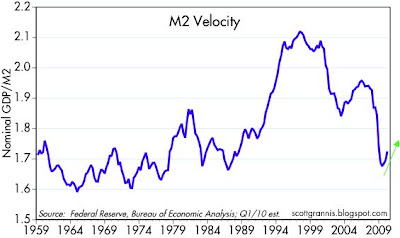

Big increases in M2 tend to occur opposite big declines in nominal economic activity, and vice versa. What this means is that the big untold story underlying all this is the velocity of money. M2 velocity (the number of times a dollar of M2 is spent for a given amount of nominal GDP) has been increasing over the past nine months, because M2 growth has slowed way down and nominal GDP growth has picked way up. That's illustrated in the next chart.

The rise in velocity has been significant, but it is only in its early stages. A better way of describing this is to say that over the past two years M2 increased by an unusually large amount. The money wasn't spent, however, it was stored. Now it is being released, and the stored-up M2 is sufficient to generate some very strong gains in nominal GDP over the next few years.

Friday, April 2, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Is it possible to know the global picture re money supply?

Have other nations expanded their rough equivalent of m2? Will velocity increase worldwide?

As the US economy becomes increasingly globalized, do we lose control over our financial future as we will be subject to what happens on the global money supply front? Seems like it--we will rise and fall with the global tide, the more we become a trading nation, for real and financial reasons.

No one talks about the money supply in Arizona vs, California. Why talk about the money supply of the US vs. the world?

How does a trading nation like Germany, with so much of its economy in trade, manage money supply issues?

Your questions are good, but not relevant. Central banks have three ways to run monetary policy: 1) control a measure of money supply, 2) control an interest rate), or 3) peg the value of the currency to something. Almost all central banks choose #2. That means money supply becomes a dependent variable, and tells you nothing unless taken in the context of the other variables and objective standards like gold, etc.

Okay, German controls interest rates. Do higher interest rates attract capital into Germany? I buy German bonds--does the money go into the German economy?

And what if (as Anthony Downs contends) we have a "Niagara of Capital." That is, global savings rates are very high. That should result in lower global interest rates. (I believe this to be true).

If we have a global glut of capital, can a central bank raise interest rates without damaging the real economy? Or does such an action simply attract even more money into an economy?

What does global high savings rates mean for international monetary authorities?

And I still have the question: If we have a globalized economy, it seems we are subject then to the actions of other monetary authorities--you say don't worry about supply, but rather interest rates.

Okay, if other foreign players are yanking interest rates this way and that, and we become more and more globalized, then we will be impacted by decisions of foreign monetary authorities to greater and greater extent, no?

It seems inevitable, for all of the obvious virtues of international trade, and seamless financial borders (it is possible now to open a bank account in China and withdraw money from their US branches), we also lose control over our economy. We rise and fall with the global economy.

We have been somewhat immune in recent deceades, as we were so large, and trade was smaller.

But, obviously, soon we will be dwarfed by Asia, and trade keep growing. Capital will flow freely across borders--not sure what this means for interest rates and the money supply.

Seems to me, we these monetary instruments become as dull as my garden shears that give me blisters.

Post a Comment