Thursday, May 19, 2011

Systemic risk remains low, so equities continue to rise

I must have showed this chart at least a dozen times since late 2008, but it's still worth showing again. The story here is that a big cause of the recession was fear: fear of an international banking collapse, widespread bankruptcies, a global depression, and just plain fear that the world was coming to an end. So it made sense to think that if and when fear subsided, then the world and the global economy would sooner or later get back on the path of growth, asset prices would recover, and that's what has been happening ever since.

In the chart above, we see that the Vix index, a good measure of the fear and uncertainty priced into the equity market, has been fairly low for over a year now, and equity prices have been slowly but surely recovering. The Vix is still somewhat elevated, to be sure, since it was as low as 10 back in late 2006 and early 2007, so the market is not entirely fearless. Ditto for credit spreads (below), which have come down a lot from their recession highs, but remain meaningfully higher than their pre-recession lows. Both indicators of fear, doubt, and uncertainty show that the market is still infused with a degree of caution, which further suggests that asset prices are not over-priced.

The upward blip in unemployment claims a few weeks ago gave the market pause, but as the chart above suggests, investors appear to understand that the rise was due to statistical noise rather than any actual weakening of the economy. In the next few weeks the 4-week moving average of claims should move back down to 400K or less, putting it back on track with a slowly rising stock market.

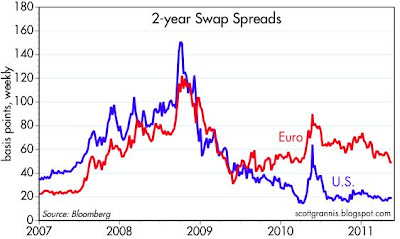

Swap spreads (above) tell a similar story. As a leading indicator of financial and economic risk, swap spreads in the U.S. are telling us that there is no reason to expect any calamity: economic and financial fundamentals are healthy, liquidity is abundant, and default risk is low. Europe is where systemic risk still lingers, in the form of looming sovereign debt defaults/restructurings. Still, the level of swap spreads in Europe is low enough to suggest that whatever problems Europe faces are unlikely to be calamitous—painful, to be sure, but unlikely to cause any significant disruption to the Eurozone economies. The market has seen the likelihood of a Greek default, it has been priced in (see chart below, which shows 2-yr Greek government yields at almost 25%, a level which indicates a very high likelihood of default), and it is unlikely to be earth shattering when it happens (German 2-yr yields are a mere 2%).

Meanwhile, life goes on, and some sectors of the stock market are at new, all-time highs, such as the relatively pedestrian consumer staples sector, shown below.

The Fed's role in all this (so far) has been to help the market deal with and overcome its lingering fears. Short-term interest rates have been set close to zero for more than two years, in part to accommodate the market's huge appetite for risk-free cash and cash equivalents. The world has been content to accumulate cash and cash equivalents paying little or no interest, as shown in the chart below. If a zero short-term interest rate were way below the market clearing rate, then the demand for M2 (i.e., the demand for cash and cash equivalents) would have collapsed, and nominal GDP would have exploded, but it has not (at least so far).

But there are increasing signs that we are transitioning out of the fear phase of this business cycle. As I've pointed out before, bank loans to small and medium-sized businesses have been growing this year, a sure sign of rising confidence. As banks lend more, they increase their deposits, and that increases the amount of required bank reserves, as we see in the next chart. Required reserves have increased at strong double-digit rates so far this year.

All of these developments are significant, and they all act to reinforce each other; rising confidence displaces fear, rising confidence boosts asset prices, and rising confidence and stronger markets fuel more investment, which in turn feeds back into more jobs, more production, and rising profits. This process is unlikely to be easily derailed, and it has a lot more room to run.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

17 comments:

Well done. What a difference a year makes. This time last year the markets were freaking out over Greece. Horror stories were conjured up by bearish investors. Euro collapse, Hindenberg Omen, and other fearful phrases were headline staples. Many commenters on this site swallowed it hook, line and sinker. Well, it's a year later and the S&P 500 is something like 20% higher. Where will it be in another year? I won't hazard a number but I will a direction. Up.

A tour de force by Scott Grannis.

Given the huge success of QE2, why not QE3?

We seem to be sagging the last few weeks, coincident with the expiration of QE2.

Well, let's see what develops in coming months. Until I saw recent weakness in light of QE2's end I was optimistic. Now I am cautious.

Also, the federal debt problem is ugly.

Scott, would you hazard any comments on Mr. Mauldin's "Endgame" thesis?

Re The Endgame, I think that first of all there is confusion about whether deleveraging is bad for growth or not. Leverage per se is not a bad thing, and debt defaults aren't as bad as they sound, since defaults don't necessarily destroy an economy's productive capacity. Debt and leverage (assuming stable, low-inflationary monetary policy) are just ways to redistribute future cash flows; they don't create growth, and so defaults don't necessarily destroy growth.

The bad thing about the US federal budget deficit is not the debt it creates, it is the inefficiencies and perverse incentives and corruption that follow in the wake of increased government spending. Government spends money much less efficiently than the private sector, so more government usually leads to a reduction in an economy's growth potential. That's where John Mauldin's 'muddle through' economy comes from.

To the extent that governments cut back spending in order to reduce debt/GDP levels that is a great thing, and I would dearly love to see it happen. I think that would result in stronger growth.

I agree with John that bad policies (monetary and fiscal) are the source of all the economic volatility we have had. So I would hope to see improvements in both these areas. That remains to be seen, however.

Excellent post, Scott. Your analysis comes greatly appreciated. Any word on what kind of P/E metrics you prefer to use measure the broad market valuation? Maybe you have an earlier post on it, please point it out - I only recently started following you.

I saw a big advisor saying that in 5+ years some of the poorest US states will takeover some productivity from China due to costs advantage.Seems strange, but if done improves bugdet.

No QE2, no rally?

Scott,

It seems like today's market action title should be "systemic risk rises, so equities fall for third straight week." Do you see a correction in the coming weeks?

Bill,

I'm sure Scott will have his opinion. FWIW, IMO market corrections of 5 to 10% are normal and healthy in ongoing bull markets, which is what I believe we have been in since the March '09 bottom. There was a ~16% correction about this time last year that lasted through the summer. That culminated in what was IMO among Scott's best posts, made in August, "20 bullish charts" at perhaps the lowest point of optimism since the March '09 lows. I will be using any correction this summer to accumulate high quality companies at marked down prices, just as last summer. A year from now, I believe they will be meaningfully higher. Just my cheap opinion.

John,

So nice to see you back on this blog. Thanks for your usual helpful comments. I'm still a bit confused about the potential threat of a Greek default. Is the market worried about it or not? It seems like its recent dips say yes, but then on other days it would appear that it's not a big threat. Do we really know how exposed banks are to PIGSs defaults or will we just have to wait and see when it happens?

Hi Bill,

The market IS worried about Greece...and the other troubled soverigns of lower Europe. But the markets are almost always worried about something. Its when the markets stop worrying that concerns me most. Greece has been 'out there' for over a year. Its old news. IMO if you read Scott's posts regularly you should get ample warning of major economic decelleration.

Its a beautiful day on the NW Florida coast. Hope its just as pretty in Atlanta.

Sorry but your graph 'Corporate Credit Spreads' does not show the spread. It shows each series and we have to interpolamate what we think is the spread.

Thee chart does indeed show the spread, which is measured in basis points. A 600 bps spread means that corporate yields are 6 percentage points higher than yields on Treasuries of comparable maturity.

From Greg Mankiw:

A Bond Market Meme

There seems to be a conventional wisdom forming that long-term interest rates in the United States are as about as low as they can possibly be. For example, this is from an article in today's Wall Street Journal:

"Rates are so low it's hard to see them going much lower, but it's easy to imagine them going higher," said Kevin March, chief financial officer of Texas Instruments.

And this is from a post at Brad DeLong's blog:

It is certainly true that most of the time when the yield spread is high the way to bet is that long-term bond rates are coming down and long-term bond prices are going up. But somehow I can't see U.S. nominal interest rates falling much lower than they are now.

I don't buy it. Why? Note this fact: The U.S. ten-year Treasury bond pays 3.18 percent, whereas a ten-year Japanese government bond pays 1.16 percent.

No, I am not predicting the United States is about to become just like Japan. But it is not inconceivable. That is why buying long-term bonds now is not a crazy investment strategy, and selling them (as many companies are now doing) is not at all a sure thing.

Addendum: Another noteworthy fact about bonds is that they have recently been negative beta assets. (You can verify this fact with this link.) Their hedging properties also make buying bonds a reasonable investment strategy.

Me talking:

I am glad more top economists are thinking about Japan. Next stop Tokyo?

Martin Feldstein called for a 20 percent correx on the Dow if no QE3. I wonder if he was right.

Robert Mundell, a big conservative monetarist, is now talking deflation.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704816604576335250426158790.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

Re: Mundell. I've known Mundell for a very long time and his track record is not exactly stellar. Mundell has made some very good observations along the way, but his arguments are not always as coherent or as cogent as Rushton makes them out to be. This is not a convincing article/argument either way.

Post a Comment