Friday, November 20, 2009

Commodity update

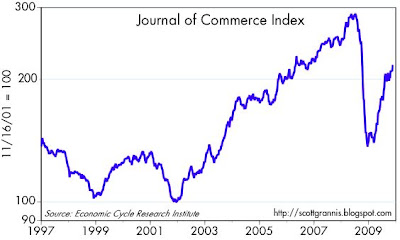

Here are two more charts to add to my commodity reflation recap post on Wednesday. The first chart is the Journal of Commerce index of 18 industrial commodities; the second chart is the textile subset of this same index. I think it's quite interesting that textile prices—hardly the stuff (cotton, burlap, and polyester) one might think would be the subject of commodity speculators—are at a new all-time high. This bolsters my view that the rally in commodity prices is a good indicator of global growth, and of growth that belies the cautious growth forecasts that I'm seeing from most sources. Accommodative monetary policies are also playing a role, but for now it would appear to be a secondary role.

Note: I've reindexed the values of both indices so their Nov. '01 values are equal to 100. I chose that date because that was when the great commodity price rally of the 2000s began.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

11 comments:

Here is an interesting fact...

California had positive nonfarm payroll gtowth for the first time since April 2008....

Very interesting, but I note that one survey showed an increase of 25,700 jobs, while another showed a decrease of 94,000. But even if the news is mixed, it's a lot better than what we have been seeing for the past year.

http://yubanet.com/california/California-s-Nonfarm-Payroll-Jobs-Increase-by-25-700.php

Agreed...here is another interesting fact 28 states showed positive nonfarm payroll growth compared to 8 states in September and 7 states in August....

Scott,

I'd be interested in your thoughts on the difficulty companies are still facing getting credit to complete transactions (which is really impacting my corporate law partners). Do you see any light at the end of the tunnel with respect to credit or do you think the banks are going to hold on to their cash for quite some time?

Monetary policy is not just "accommodative;" short term interest rates have been artificially managed to an ultra low level. Banks and investment banks can borrow at a few basis points, and there is a growing number of people who believe the US dollar has now become the carry trade source of the world.

Given nearly zero interest rates, lots of economic projects appear to be feasible, even though they would not be in a normal free market environment. I don't know how you can conclude that this artificial environment is a relatively unimportant contribution to the statistical trends you are identifying. The question is: how many economic projects will be revealed as "malinvestments" when the policies change?

Time will tell. My guess is that the next crisis will be more severe than the crisis spawned by the bursting housing bubble -- which was more severe than the crisis caused by the bursting tech bubble.

Scott:

I think Iread in the paper recently that a Fed Gov. said that interest rates are being kept where they are to encourage investments in riskier things, stocks etc. Any thoughts.

Jay

Here's how I see the issue of zero interest rates. This whole crisis began with an enormous increase in the world's demand for dollars. To avoid a general deflation, the Fed responded with an attempt to satisfy the world's demand for dollars by lowering the interest rate on dollars to zero. In addition, the Fed went on to purchase $1 trillion or so of agency and MBS, to ensure that the banking system would not experience any restrictions on its ability to satisfy the demand for dollars.

With interest rates at zero, the Fed is trying very hard to makes the world want fewer dollars. Making it easier for the world to borrow dollars is equivalent to encouraging the world to demand fewer dollars (very important note: borrowing dollars is equivalent to selling or shorting dollars, and that is the opposite of demanding, buyer, or being long dollars). If dollar demand declines because of zero interest rates, then most likely the demand for risk assets of all sorts will rise.

We don't yet know how exactly how successful the Fed has been in not only offering tons of dollars to the world, but also actively encouraging the world to want fewer dollars, but the rise in gold and commodity prices suggests they have had at least some success.

The Austrian School economists believe that the natural interest rate is determined by human "time preferences" -- and they believe the market determined interest rate coordinates important economic decisions.

The Fed's notions, as you explain them, have destroyed the interest-rate coordination mechanism in our economy. This is not a good thing. During the last boom it led to a huge excess investment in housing, in commercial property, in manufacturing capacity (in Asia), and moved lots of people into unsustainable occupations. Similar, but different, economic dislocations will flow from these even more extreme interest rate manipulations.

The economic turn down was not caused by the demand for dollars. The demand for money was caused by the destruction of capital which resulted from all these failed investments. People were left with assets worth less than the debts that built them -- so they needed lots of money to remain solvent.

The demand for money will remain high if the Fed is willing to exchange money for securities of questionable value. Why wouldn't the banks want to "sell" all of their junk to the Fed, if it would take it? In free markets a high demand for money is satiated when the price of money (in terms of goods they must exchange for money) rises high enough to bring demand and supply into balance. With the Fed willing to supply a seemingly infinite amount of money at lower and lower prices, it's no wonder the demand was "incredible."

The crisis began with a lack of confidence in banks and insurance companies ability fulfill their debt obligations.

This crisis in confidence stemmed from the ability of banks and insurance companies to leverage 30+ times using ultra cheap credit.

The source of the fuel for the crisis that the banks and insurance companies used to lever up stemmed from shakey credits in housing and commercial real estate, which in turn stemmed from cheap credit.

Cheap and unjustifiable credit is the common denominator throughout all of this.

The current situation is no different. Too much cheap credit provided by the Fed.

I think that is equivalent to what I've been saying. The weak dollar and rising gold and commodity prices say that the Fed is too easy. Treasury yields are very low, and will probably rise significantly once the Fed gives the all-clear sign on the economy.

Bill: I think I've mentioned before that we are in a strange environment: money is quite plentiful (more than ever before), but for some people it is very hard to get. I think this is due to the huge changes sweeping the financial industry (not all good, unfortunately) and the fact that the world is still quite risk averse. Traditional lending channels aren't working as well as they used to. It will take time to rebuild lending channels, and perhaps they will function in new and innovative ways, but in the meantime it's going to be hard for some to access the credit markets. Eventually, lenders and borrowers are going to reconnect, but it's going to be a challenge. Your partners are going to have to think outside the box to solve their problem quickly.

Post a Comment