And that means inflation has peaked and will be headed down in the months to come.

Inflation as measured by government indices (e.g., CPI, PCE Deflator) is a lagging indicator of true inflation. True inflation is defined as the loss of purchasing power of a currency. Right now that is just not the case: the dollar is soaring against nearly every currency in the world and virtually all commodity prices are collapsing. Don't pay attention to inflation; pay attention to sensitive market-based prices—they tell you where inflation is headed.

The Fed was very slow to see the inflation problem which showed up in surging M2 growth in 2020, and they are being very slow to see that inflation fundamentals have improved dramatically this year.

Chairman Powell has it all wrong: the way to kill inflation is not to kneecap the economy, it's to reduce the supply of money and increase the demand for it by raising interest rates. The Fed has already succeeded in doing that! There's no reason at all that we need a recession to get inflation down. In fact, a growing economy can actually help to bring inflation down by increasing the supply of goods and services. I just don't see the Fed continuing on the inflation warpath for very much longer.

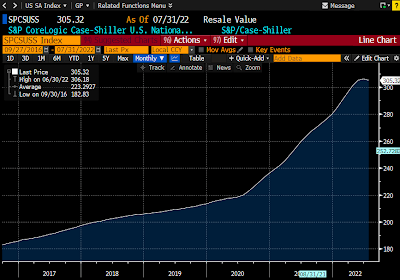

Chart #7 shows the best measure of US housing prices. Note that prices stopped rising a few months ago according to this measure. However, since the index is based on an average of prices over the previous three months, it's quite likely that the actual peak in housing prices happened some time in the March-April time frame. And it's not at all surprising that housing prices have peaked considering that mortgage rates have more than doubled so far this year (most recent quote is 6.7% for a 30-yr fixed conventional mortgage). This is how monetary policy impacts prices and inflation: higher rates increase the demand for money and reduce the demand for borrowed money; people become much less anxious to own things when interest rates are high. It's better to hold on to your money than spend it; better to rent than buy, which is why rents are increasing as housing prices soften.

Chairman Powell has it all wrong: the way to kill inflation is not to kneecap the economy, it's to reduce the supply of money and increase the demand for it by raising interest rates. The Fed has already succeeded in doing that! There's no reason at all that we need a recession to get inflation down. In fact, a growing economy can actually help to bring inflation down by increasing the supply of goods and services. I just don't see the Fed continuing on the inflation warpath for very much longer.

This bad Fed dream will be over soon. This is not the time to be cashing out of risk assets.

Chart #1

The dollar is very strong and rising against virtually every currency in the world (Chart #1). That means that most prices outside our borders are going down. Come to Argentina, where I am at the moment, and you won't believe how cheap things are. Great wine for $3-5 per bottle. Steaks for $3. A 1-mile Uber ride for $1. Tip a cabby with 1000 pesos (the largest-denomination bill, but worth only $3.33 US) and they will sing your praises. We have a 3-room suite in a nice hotel for only $70 a night. To worry about US inflation at a time like this is crazy.

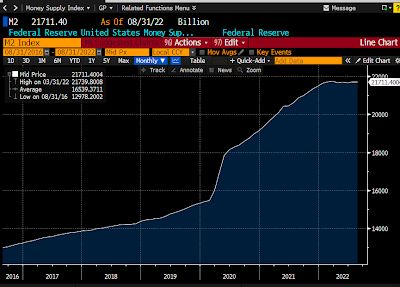

Chart #2

The M2 money supply (Chart #2) has risen at a paltry 2.3% annualized rate over the past 9 months, and M2 has been flat for the past 6 months. If rapid M2 growth beginning in 2020 was the fuel for inflation (very likely), then the inflation fires are already dying down. The surge in M2 that began in 2020 was the spark that triggered rising inflation about a year later; the lack of M2 growth that began late last year will undoubtedly result in a decline in measured inflation before year end.

Chart #3

The CRB Raw Industrials index (Chart #3) is down 18% since its early March high. Nearly every commodity has exhibited the same behavior, as the following charts show.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows copper prices, which are down 35% since March. "Dr. Copper" is telling us that the Fed has no reason to worry. But maybe they should worry because they are threatening a whole lot more tightening when none is needed. This is what is called "closing the barn door after all the horses have left."

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows gold prices, which are down 22% from last March's high. Gold is traditionally very sensitive to changes in monetary policy. This is a strong signal that the Fed may have already tightened too much.

Chart #6

Chart #6 shows crude oil prices, which are down a whopping 35% since mid-June. This is a very significant decline that will have the effect of lowering the prices of all things that depend on energy.

Chart #7

Chart #8

Finally, as Chart #8 shows, the market's expectation for what CPI inflation will average over the next 5 years has now fallen to 2.33% (the bottom half of the chart), thanks to a huge increase in market interest rates (top half, representing 5-yr Treasury yields and 5-yr TIPS yields.

Markets these days are a lot more worried that the Fed will needlessly kill the economy than that inflation will do anything but decline.

UPDATE: We've been in Argentina for a week now, and it's painful to see the sorry state of the economy and the abysmal level of prices. Food here costs about one-fourth what it does in the U.S., not because unemployment is high (which it is), but because no one earns enough to afford to spend more. Those pundits who argue that the Fed needs to tighten by enough to push unemployment higher so that inflation will come down should come to Argentina to see the results of high unemployment. Prices for basic things may be low, but the inflation rate here is about 100% a year. Anything produced outside of Argentina comes in at international prices, and sooner or later the prices of basic things will necessarily rise to international levels. Things are cheap here only temporarily. The lower and middle classes are being robbed of their purchasing power by inflationary monetary policy, and the only one benefiting from the theft is the government. That's called the inflation tax. The government prints money to pay its bills, and anyone who touches that money loses purchasing power on a daily basis, while on the other side of the coin the government gets to keep on spending. Bottom line: Argentine M2 is growing by leaps and bounds—70% a year at last count, whereas in the US, M2 is flat. The US is on the cusp of disinflation, while Argentina is on the cusp of hyperinflation.

If higher unemployment were necessary to bring inflation down, Argentina would be suffering from deflation by now.

38 comments:

Another great wrap-up by Scott Grannis.

The dollar's strength against Asian currencies is remarkable. You are seeing 25% appreciation against the Thai baht or the Japanese yen in 2022.

Beijing/CCP are in knots over what to do on the yuan, which is also depreciating.

If America's leadership wants to fight inflation, they should plan a way to a national moratorium on property zoning.

the inflationist is getting desperate to re-inflate his stocks

Scott:

Thanks for this. I agree with your analysis. My concern is that the supposedly smart people leading the Fed and the Treasury Department may not have grasped your point that inflation has already peaked.

How about velocity? Where is that headed?

Scott, thanks. As usual you're the adult in the room.

Two questions?

(1) Do you have a sense as to why the Fed continues to see the need to raise rates? These are obviously smart people. Are they subscribing to some alternate economic theory? Reacting to sentiment? Political pressure?

(2) It's great to "tame" inflation, but prices have gone up over the last year plus, and I'd like them to go back to where they were. Is there an economic path for that to happen without us entering a recession?

Thanks in advance!

Re "what about velocity?" Velocity has definitely picked up (which is to say the demand for money has definitely declined). Velocity, typically defined as the ratio of GDP to M2 (which is the flip side of money demand, M2/GDP) has picked up from a low of 1.074 in Q2/20 to (I estimate) 1.7. Money demand, correspondingly, has fallen from a high of 0.93 in Q2/20 to now (I estimate) 0.86. I prefer to talk in terms of demand. The demand for money has declined because there is less uncertainty in the world now than there was when Covid fears were raging. Economies are now getting back on track and Covid is like a bad dream.

There is still an unusually large amount of money in the economy, however, which means that money demand has lots of room to weaken further. The Fed's job therefore is to take steps to strengthen the demand for money (otherwise it will get spent and boost inflation). That is easily accomplished by raising interest rates, and that is what they have done.

Re "can prices go back down to where they were?" Theoretically they could, provided the Fed keeps rates high enough to cause money demand to rise. In practice that could be difficult. I'm guessing that the best case going forward is for measured inflation to subside (i.e., disinflation) gradually over the next year. That would leave prices relatively stable, but at a permanently higher level that pre-Covid. We can't just make the multi-trillions of dollars of Covid "stimulus" disappear and the Fed can't withdraw such a massive amount of money from the economy without wreaking havoc.

Re "why can't the Fed figure this out?" I think this is simply a case of the Fed reacting to events rather than being proactive. They were slow on the uptake and they are now being slow on the reversal. The Fed is more often a follower of the market rather than a leader (I've discussed this numerous times over the years). The Fed works like any committee tasked with making big decisions: it takes a lot of time since it requires consensus, and at times like today, consensus is very hard to come by (lots of confusion). The Fed made a similar mistake in late 2018, when they began talking tough, only reverse themselves in early 2019.

Also a factor: the Fed was effectively blindsided by events and now they want to act tough in order to avoid losing their credibility. Once it becomes painfully obvious that they are too tight they will be able to ease and then claim credit for having done the right thing.

Re "does the Fed subscribe to some alternate economic theory?" Yes, and it's name is the Phillips Curve, which posits that unemployment must rise if inflation is to fall (conversely, inflation is believed to rise as the unemployment rate (barometer of the health of the labor market) falls. This explains why the Fed has never once mentioned the growth of M2; they just don't believe the amount of money has anything to do with inflation. Instead they believe that inflation rose because "demand" was just too strong; so the key to lower inflation is to destroy demand (i.e., weaken the economy with higher interest rates).

I'm a more traditional monetarist. I believe inflation results from an imbalance between the supply of money and the demand for it. We've seen a huge increase in the amount of money in the economy, and that was followed by a decline in the demand for money (because of rising confidence), with the result being higher prices. The solution therefore is to shrink the amount of money (by selling bonds and reducing the Fed's balance sheet) and boost the demand for money (by raising interest rates).

Hi,

I have read below:

“Total bank assets have actually accelerated this year. Moreover, the Treasury ran a massive surplus in April and that took M2 out of the system.”

Any rebuttal?

Thank you

re: "Chairman Powell has it all wrong: the way to kill inflation is not to kneecap the economy, it's to reduce the supply of money and increase the demand for it by raising interest rates"

On point. Interest, as our common sense tells us, is the price of obtaining *loan- funds*, not the price of *money*. The price of money is the inverse of the price level (as you point out). If the price of goods and services falls, the “price” of money rises.

The economy is being run in reverse. There have been 12 boom/busts in the housing cycle since WWII (including Covid-19’s)

Higher interest rates impound savings, inducing nonbank disintermediation.

CBs’ disintermediation is not predicated on interest rate ceilings.

Disintermediation for CBs can exist only in a situation in which there is both a massive loss of faith in the credit of the banks and an inability on the part of the Federal Reserve to prevent bank credit contraction as a consequence of currency withdrawals from the banking system.

The last period of disintermediation for the CBs occurred during the Great Depression, which had its most force in March 1933. Ever since 1933 the Federal Reserve has had the capacity to take unified action, through its “open market power, to prevent any outflow of currency from the banking system by forcing the banks to contract credit.

Scott, you write above " I'm guessing that the best case going forward is for measured inflation to subside (i.e., disinflation) gradually over the next year. That would leave prices relatively stable, but at a permanently higher level that pre-Covid."

Not sure what level you believe inflation would settle at when you discuss "permanently higher than pre-covid" but many people have a recency bias here. Inflation over the past 6 decades has averaged 3.27% in the US and I'd be surprised if the permanently higher level exceeds this. It may, but it may not. Currently the bond market doesn't think it will (when looking out 5-10 years). We will see if they are correct.

@Shane

I believe Scott was referring to absolute prices relative to pre-COVID levels not the rate of inflation, which seems likely to settle in the ballpark of where it was before the pandemic.

Variant: you are correct. Shane confuses the level of prices with the rate of inflation. Inflation raises the level of all prices. If inflation falls to zero, the level of prices will no longer rise, but prices will be higher than they were before inflation went up.

Hello,

What about the story, that there is no buyers for US bonds,rather forced sellers, i.e. Japan and China to name the biggest names. So the yields can rise much further decoupling from FED's policy.

Scott thank you for the post. As you mentioned, M2 doesn't grow for 6 months. However, the elevated M2 excess requires 5-6 years to be flat to return to the multiyear M2 line slop. Does it means that Fed requires to keep the interest high enough (higher than inflation) for the same period of 5-6 years to support demand over spending? Or I miss something?

Scott, thoughts on LDI’s and it’s ability to have an affect on the US like it did in the UK?

https://www.ft.com/content/f4a728a5-0179-48bd-b292-f48e30f8603c

Scott, thank you for your post and all the others I have read for the last fourteen years. You are insightful and wise. It is hard to believe that the Fed gets it wrong so often despite having immense resources including hundreds of PhDs in economics on the staff but they do. Secondly, I am interested in Argentina travel. Are your observations about prices there rural areas or big city? What area is your favorite?

@AI re: "that took M2 out of the system.”

Savers never transfer their savings out of the banks unless they hoard currency or convert to other National currencies, e.g., FDI. I.e., savings flowing through the nonbanks never leaves the payment’s system. There is just an exchange of preexisting deposit liabilities between counterparties in the banking system.

Re Argentina travel: You will find things are amazingly cheap just about anywhere in the country, but the further you go from Buenos Aires the cheaper things tend to get (but not dramatically so). Also, you should avoid going to American/International hotels and tourist trap restaurants, since they can be much more expensive. Go where the locals go and you won't be disappointed.

One important consideration, however, is the exchange rate. The official rate is about 150 pesos/dollar, and that applies to credit card and bank transactions. The "blue" rate is the unofficial, market, or "black market" rate, and it is currently about 300. (Double the bang for your buck) In order to benefit from the blue rate you must avoid using a credit card. You can take dollar cash with you to Argentina (stick to clean $100 bills) and exchange them at restaurants (not all, but most do this) and some retail establishments and some hotels. Another way is to use Western Union. Send yourself $1000 the day you depart, for example, via Western Union's mobile app, specifying the destination country as Argentina. When you arrive in the country, go to any WU kiosk (there are lots of them everywhere, usually to be found in retail shopping areas) and present your WU code and your passport and they will happily hand you a huge bundle of pesos (300 bills, since the largest denomination is $1000 pesos). The smaller WU kiosks may not have that much cash on hand, but the larger ones do.

before the dot com boom/bust it was commonly believed 6% unemployment was full employment. the 10yr bond's avg yield was about 6% as well and was viewed as a balanced rate for growth. if you look at fed fund activities over the last 70 yrs you'll see the spikes. point is, we have been experiencing major inflation, but rates are far too low to combat HEADLINE INFLATION numbers (vs what the avg american is experiencing).

... i think the 10yr bond returns to 6% before all is said/done.

I sense that the Fed intends to accelerate expansion of the money supply , and that the Fed (and other central banks) are using interest rate hikes to mask the intended expansion of the money supply -- said another way, the only way to save the dollar is to conjure more dollars ad infinitum -- global de-dollarization is the center of gravity for the US today -- crime, pandemics, famine, war, and energy are smoke screens to the dollar crisis -- to be honest, I doubt the dollar can survive as the world's reserve currency.

"Velocity, typically defined as the ratio of GDP to M2 (which is the flip side of money demand, M2/GDP) has picked up from a low of 1.074 in Q2/20 to (I estimate) 1.7."

From the Fed:

M2 velocity Q2 2020 1.112 now 1.165

If you adjust for excess reserves (asset inflation not consumer inflation money flows):

Adjusted M2 velocity Q2 2020 1.346 now 1.381

-----

To the extent the concept of money demand (which also has a quantity aspect) bears an impact on money velocity (which is essentially a flow concept), velocity has been mostly flat despite unprecedented monetary/fiscal easing. Also, using the adjusted measure, a peak of 1.419 was reached in Q4 2021 so money velocity has started to come down.

-----

Given the strong trajectory down of money velocity measures for the last 20 years or so, why one would expect to get out of a hole if the overall strategy is to keep digging?

-----

It's cumbersome but 'we' need higher interest rates, somehow.

Have you pondered that we are following the footsteps of the BOJ in the late 80s and our Dow may follow the pattern of the Nikkei?

"Have you pondered that we are following the footsteps of the BOJ in the late 80s and our Dow may follow the pattern of the Nikkei?"

Please elaborate your thinking.

-----

In the late 80s, the BOJ started to tighten in order to contain inflation pressures which were building and then (up to this day!) have tried to ease enough in order to get the productive engine going again and some would contend that this was a slow-death strategy. My bet is that the US will do better but that may require the recognition that the emperor has no clothes.

I use a few (~4) indicators to estimate GDP, which are coincident or lagging. So far they have not shown recession. They have been flat to slightly improving over this calendar year.

I use about 5 asset classes to monitor the financial markets, which are somewhat leading indicators for the economy. All of these are now pointing down.

This bear market hasn't lasted very long, and the duration of a bear market is an important indicator.

So, I would guess the markets and economy are not looking good for the next few months, at least.

Income velocity, Vi, is meaningless. Vt may move in the opposite direction. The rebound in R-gDp is due to the reversal of money flows. The demand for money has fallen, while the means-of-payment money has risen. It is likely to force the FED to tighten faster than now expected.

Link: George Garvey:

Deposit Velocity and Its Significance (stlouisfed.org)

“Obviously, velocity of total deposits, including time deposits, is considerably

lower than that computed for demand deposits alone. The precise difference

between the two sets of ratios would depend on the relative share of time deposits

in the total as well as on the respective turnover rates of the two types of

deposits.”

But Powell sums up all deposits together and claims M2 is worthless: “We have had big growth of monetary aggregates at various times without inflation, so something we have to unlearn.”

The FED doesn't know a debit from a credit, nor money from mud pie.

Historically, the markets bounce when R-gDp rises.

The markets' problem is the Keynesian macro-economic persuasion that the banks are intermediary financial institutions, the Gurley-Shaw thesis. Disintermediation is made in Washington. The payment of interest on interbank demand deposits induces nonbank disintermediation (like the 2019 repo spike) or a decline in the supply of loanable funds. I.e., the banks outbid the nonbanks for loanable funds.

Savings flowing through the nonbanks increases the supply of loan funds, but not the supply of money - a noninflationary velocity relationship.

see: “Should Commercial Banks Accept Savings Deposits?” Conference on Savings and Residential Financing 1961 Proceedings, United States Savings and Loan League, Chicago, 1961, 42, 43.

Strange, dangerous $US loop?

As I understand it, because the UK (rest of Europe?) trades a lot in $US, and requires such trade (read de-industrialization of UK & Europe), the $US strength is causing a lot of pain.

Pensions going bad because domestic bonds are tanking, requiring a bailout by the govt. This sounds like a kind of "bank run". People would be selling these bonds in a panic without govt intervention.

I have thought for some time the pension system(s) in the US would be the focus of some kind of panic (including social security, private, and private pensions).

Can this be contagious to the rest of the world?

Well, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) raised it key rate only 0.25% yesterday instead of 0.50%, and that led to a rally in Sydney.

I do not know why the Fed thinks it has to keep raising rates in huge chunks. Steady smaller increases might be better.

BTW the Fed is also operating a huge "reverse repo" program. (This is so complicated it makes me want to go back to the gold standard).

OK, it goes like this: The Fed is selling Treasuries, called a "reverse repo operation." They have sold net about $2 trillion worth outstanding so far.

Is this a form of reverse QE? (QT)? Some say it is not.

The commercial banking system seems to like the reverse repos.

"Is this a form of reverse QE? (QT)? Some say it is not.

The commercial banking system seems to like the reverse repos."

From a balance sheet perspective, reverse repos are exactly the opposite of QE and both 'operations' are run concurrently.

Out of the 2.2T now outstanding, 1,9T accrued to money market funds.

Reasons:

-Commercial banks reached saturation point for deposit growth (many reasons including regulatory liquidity ratios, SLR rule etc)

-Excess money created by the Fed (asset swap for government security) was diverted to money market funds

-As a result of relative scarcity of Treasury bills (despite high issuance, the Fed was buying them all), money market funds had nowhere to turn to but the reverse repo window at the Fed.

A lot of the money 'created by the Fed went back to the Fed.

-----

The reverse repo facility is just another tool for the Fed to put a floor on short term interest rates.

Simple Answer:

REPO: infuses capital into financial institutions

REVERSE REPO: drains cash fr finacial institutions.

The FED's accounting is obviously wrong. If it were term deposits, instead of O/N deposits, maybe the accounting would be different.

-As a result of relative scarcity of Treasury bills (despite high issuance, the Fed was buying them all), money market funds had nowhere to turn to but the reverse repo window at the Fed.-Carl

I do not disagree with you.

But the relative and market-driven scarcity of Treasuries should drive Treasury interest rates down.

In other words, is the Fed artificially holding rates higher?

There is a global glut of capital and we have globalized capital markets.

Maybe people "should" get negative returns on ultra-safe assets.

Mr. Market is signaling that savings are not valuable.

Not a popular thought---but a true thought?

LSAPs create new credit. The monetization (operations of the buying type), and sterilization vis-à-vis remunerating IBDDs (destroys velocity) decreases the demand for loan funds, while increasing the supply of loan funds.

It's an artificial suppression of real interest rates. It's backwards. Whereas the activation of monetary savings by the intermediary financial institutions (nonbanks), increases the real rate of interest. The FDIC's Dec. 2012 reduction in deposit insurance is prima facie evidence.

Rather than bottling up existing savings, the monetary authorities should pursue every possible means for promoting the orderly and continuous flow of monetary savings into real investment.

The problem is that the FED doesn't know that it's already tightening. Not only does the FED eschew the notion of monetarism, but it also eschews the notion that there is a lag to monetary policy. The FED conflates hiking interest rates with "tightening". Another hike in the administered rates will come at the same time long-term money flows are already decelerating.

This upcoming hike in rates is a lot like Volcker's 1st and 2nd qtrs. in 1980. Volcker didn't understand monetary lags. That was a good time to sell gold.

Post a Comment