Time for a review of some key charts that I'm following. On balance, I see evidence that inflation is running about 1 ½% to 2%, as it has for the past 15 years or so. I find very little, if any, evidence that monetary policy is too tight or that deflation is likely or a real threat. This suggests that the market is overly concerned about the Fed "running out of ammunition," and overly concerned about the risk of a "downward spiral" that might be sparked by an outbreak of deflation (i.e., people stop spending because money acquires more value with time). It all but rules out the need for negative interest rates, which could be potentially dangerous since their purpose is to destroy the demand for money, and it suggests that the Fed was justified in making a modest increase in short-term interest rates. I also see reasons to think the market may be too pessimistic about the outlook for economic growth.

The Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Deflator (above charts) tend to track each other, with the CPI running about 30-50 bps higher the the PCE deflator due to differences in the basket of goods and services measured by each. In the past year or so, both measures dipped close to zero, due mainly to collapsing oil prices, but they have recovered significantly in recent months. Meanwhile, the core and ex-energy versions of both have been relatively stable: the CPI ex-energy is up 2% in the year ending January '16, and the core PCE deflator is up 1.7% over the same period. Both have accelerated a bit of late, which runs counter to the prevailing notion that inflation is dead. With oil prices stabilizing, it's therefore quite likely that the headline CPI will hit 2% within a few months, and the PCE deflator will be close behind. In the world of macroeconomics, this is as close to the Fed's target of 2% on the PCE deflator as one could hope for, and there is no reason for a shortfall of even ½ % to be of concern. Arguably, the ideal rate of inflation would be 0-1%, but I'd be happy with 1 ½%.

As the chart above suggests, one important source of low inflation over the past 15 years has been declining prices for durable goods (e.g., computers, electronic gadgets, appliances). Durable goods prices on average have fallen by one-third since 1995. At the same time, the prices of "services" (which are mostly driven by the cost of labor) have increase by more than two-thirds. Thus, the deflation of durable goods prices means that an hour's worth of labor buys two and a half times more durable goods today than it did in 1995.

The source of this "deflation" can be traced rather easily to China, which became a significant exporter of cheap durable goods beginning in 1995. (Durable goods prices never experienced a sustained period of decline prior to 1995, by the way.) The collapse of energy prices in the past year or two shows up in flat to declining prices of non-durable goods, which have depressed inflation of late.

It's a mystery to me why folks like Donald Trump say that China has been stealing our jobs, when thanks to cheap Chinese goods the purchasing power of the entire country has increased significantly.

So: is inflation low because the Fed been too tight? I think not. Inflation has been low mainly because of supply shocks: China's export boom, and fracking technology which has significantly boosted oil production, which in turn has resulted in collapsing oil prices.

The chart above shows the market's expectation for the average annual inflation rate over the next five years (green line), as derived from the yields on 5-yr Treasuries and 5-yr TIPS. Currently 1.32%, expected inflation is lower than the current level of core inflation, and lower than the 2% average inflation rate of the past 15 years. If anything, this suggests the market may be underestimating inflation. If so, then it would stand to reason that the bond market is quite vulnerable to any sign of rising inflation.

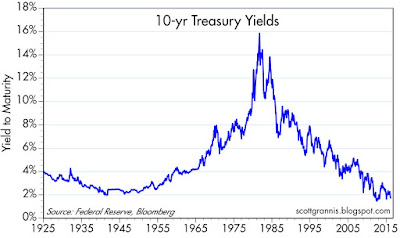

With 10-yr Treasury yields currently a mere 1.73%—only 25 bps above their all-time lows of mid-2012—the bond market is priced to slow-growth, low-inflation perfection; it's vulnerable to any sign that inflation is either not falling or rising, and/or any sign that economic growth is, say, 2% or better.

Extremely low Treasury yields are also a good sign that the market is consumed by pessimism, given that the earnings yield on equities is 5.7%. Choosing 10-yr Treasuries with a yield of only 1.7% in lieu of equities yielding 400 bps more (and considering further that equities have far more upside potential than bonds at this point) only makes sense if one is convinced that earnings will suffer significantly in the years to come. So far, earnings are down only a little more than 2% in the past 12 months, and most of that is coming from the oil patch. Put another way, the current PE ratio of the S&P 500 is 17.4, whereas the PE ratio of the 10-yr Treasury is 58! To pay so much for the presumed safety of Treasuries is to have truly dismal expectations for economic growth and corporate profits.

About 10 years ago I put together the chart above in order to illustrate how tight money (as reflected in rising real short-term interest rates) and high and rising oil prices conspired to trigger the recessions of 1990-91 and 2001. (As I described it then, the economy gets "squeezed" by expensive money and expensive energy, as illustrated by the blue and red lines converging.) The same thing happened with the recession of 2008-9, as oil prices reached record-high levels and the Fed raised the real Fed funds rate (its primary policy tool) to over 3%. If tight money and expensive oil have traditionally been bad for the economy, then today's negative real rates and cheap oil prices are likely a godsend. This suggests that the economy can do better than the market expects, even if it only continues to grow at 2 -2 ½%, as it has since 2009.

The chart above illustrates how Fed tightening has preceded every recession since the late 1950s. Recessions have always followed the confluence of high and rising real interest rates (the blue line) and flat to inverted yield curves (the red line). Today, real rates are still negative and the yield curve is still positively-sloped. Monetary policy thus appears to pose no threat to economic growth, at least as far as the bond market is concerned. Otherwise the curve would be flat in the expectation that a recession would make it impossible for the Fed to ever raise rates from their current level.

This recovery continues to be the weakest in modern times. As I pointed out a few weeks ago, the main culprit is extremely weak productivity gains. As the chart above shows, real disposable personal income would be about $1.5 trillion per year higher today if this had been a typical recovery. That's a lot of income left on the table, and it explains why the middle class is not happy with the current state of affairs. Trillions of dollars of prosperity are riding on the results of the November elections, with only Republicans proposing policies that could change things for the better (e.g., reduced marginal tax rates, tax code simplification, reduced regulatory burdens).

Markets are still very worried, of course, as the chart above shows. The Vix index is unusually high, the 10-yr Treasury yield is quite low, and equities are still down almost 10% from their highs of last May. The pattern in the above chart (i.e., spikes in the Vix/10-yr ratio coinciding with plunges in the S&P 500 index) has been repeated quite often in recent years, only to be resolved with higher equity prices as fears decline and confidence returns. The recent decline in the Vix/10-yr ratio is thus encouraging, as is the lack of evidence that the problems in the oil patch are spreading. Still, there are many ongoing calls for a sharply lower market and a worsening of economic conditions. But from what I see, there is no reason to panic. A simple continuation of what we've seen in recent years should be enough to support equity prices at current or higher levels. In the end, avoiding recession is all that matters, as I've been saying for the past three years.

17 comments:

Lots of great charts and commentary.

Still, 10-year Treasuries at 1.7% suggest institutional investors expect a very, very tight Fed for a long, long time. Maybe we are arguing semantics here. Maybe one man's tight is not another man's tight. Ten years ago, if you asked anyone about 1.7% interest on 10-year Treasuries, they would say that means a central bank has beaten inflation dead and for a good long time.

The 2% Fed inflation target is supposed to be an average target, not a ceiling. Maybe 2% is a bad number. But if it is the Fed's number, then they should run between 1.5% and 2.5% on the PCE, and do what they say they are going to do.

I think Scott Grannis is correct, and the Fed in fact regards 2% on the PCE as a ceiling, despite its stated target.

Whether an economy loaded with structural impediments such as the US--rural subsidies, ubiquitous property zoning, a $1-trillion-a-year national security complex, FICA taxes, the ACA, the minimum wage--can prosper at such microscopic rates of inflation is yet to be seen. It strikes me as a highly risky and precarious course to follow, promising endless economic and financial instability.

One thing for sure--we won't see the next recession, and when it hits the Fed cannot lower rates much, before hitting zero again. The Fed will have to turn to QE, but that remains taboo and politically risky.

Jeez, were the 1980s-1990s so bad? Moderate inflation and great growth?

scott, total agreement. if energy holds anywhere near current levels, corp hy could be THE trade of the year and I am long (buyer beware, I am a trader and I'm good at this having been doing it for 20 yrs +). I think the trump/sanders phenomenon has lead us down this pessimistic path and for some reason people (voters) are buying it. I learned a long time ago to never doubt the stupidity of the average american voter. ever watch "water's world"?

After the Japanese combined equity market / housing market bubbles of the late 1980s - for more than 25 years, Japan has had extremely low growth and frequent recessions.

Not once has their sovereign yield curve inverted.

The US had their equity bubble in the late 1990s and housing bubble in the mid 2000s and has had extremely low growth since. Just saying....

Scott To say that innovation is not part of the inflation complex is wrong. In a sense, the shift of manufacturing from America to China (lets be clear it was simply an acceleration of an already present trend) is a reasonable component of the inflation complex. What is amazing, is that in those industry where "American labour" cannot be replaced inflation remains strong.

Finance and education are good example of sector that have so far escaped globalizations. I can easily see technological shifts in finance, that will lead to a massive reduction in cost of operations, from smart systems to simply Fintech -- they are having a massive impact on service inflation. Education has been seeing price inflation at double digit rates for nearly 25 years. There too changes are afoot.

All I am saying is that technology (whether its new drilling technology or Fintechs) will have an impact on future inflation. The market seems to agree that inflation will remain subdued -- since they are buying tightly priced long bonds.

As for your preference of inflation at 1% or 1.5% rather than 2%... well that's just your preference.

BTW thank you for your analysis, I agree with about 90% of what you say (I agree more with you than I agree with myself!)

Frozen: If I somehow implied that innovation had nothing to do with inflation, then I apologize. Innovation lets us produce more from a given set of inputs, and that's productivity in a nutshell. It expands the economy and a larger economy creates a greater demand for money. If the Fed doesn't respond by also expanding money, then innovation can lead to lower inflation or even deflation.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/CUUR0000SA0L2 (CPI Index for all Urban Consumer: All items less shelter)

Looks like housing is really what has kept the CPI in positive territory. Looks like we haven't seen CPI increase in total in about 3 years excluding housing.

Seeing the same thing with corporate profits (https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/CPATAX) which haven't really increased in about 3 years.

Total business sales don't look very positive (https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/TOTBUSSMNSA).

Seeing C&I lending tighten two quarters in a row for the first time since 2007. (https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=3ntH)

https://www.frbatlanta.org/cqer/research/shadow_rate.aspx?panel=1 (shadow rate shows a high and rising real interest rate)

More CB balance sheet expansion to fuel this growth cycle for longer? ECB meeting next week and the Fed in two weeks. More QE please!

Imagine the prosperity that would result (from a significant decline in uncertainty) from an asset-backed currency. If the Fed announced (and we all believed it) that it would target a range of gold, say 1250 plus/minus 25. Or, for those of you who are allergic to the word "gold," how 'bout a basket of 20 different commodities?

We could do away with all these definitional problems as well as the debate about the impact of technology on prices. CEOs could actually plan their businesses better and politicians would be more answerable for their stupid spending. As an added bonus, war making would be made more difficult.

Thinking Hard: CPI less shelter does not obviate the huge negative impact of energy prices. yes, the shelter component of CPI is up faster than the core CPI (3% vs 2%), but energy costs have fallen by orders of magnitude. Energy remains the dominant factor in CPI.

Lending standards may have tightened, but lending is still growing at very strong rates (8-11%).

The growth cycle is not being "fueled" by QE. The Fed is not printing money. (In fact, the Fed CAN'T print money.)

More QE might help, since the demand for safe assets remains strong.

Approx. $10T in worldwide CB balance sheet expansion is not fueling the growth cycle? Good summary by Yardeni here http://www.yardeni.com/pub/peacockfedecbassets.pdf

Why the huge increase in assets held by the CBs? Looks like a global shift in monetary policy because interest rates can only go so low...which leads to a question of how low can they go? Higher liquidity, lower interest rates equates to spurring more lending and borrowing.

Think we are topping in buybacks? (http://www.yardeni.com/Pub/buybackdiv.pdf) Would like to see tax-free or at least lower taxed dividends by the way. Corporate debt up a couple trillion dollars since 2007 seems to assist in this equity growth cycle.

I agree that the Fed is not printing money directly (BEP does that), but the derivative effects ultimately lead to increased credit growth.

With fracking technology revolutionizing oil production, it seems less likely energy will be a big contributor to the upside in CPI. Fracking is just getting started in countries like Argentina. Energy still remains a dominant factor in CPI, but is this time different? Don't like to use "is this time different" but fracking technology increases have revolutionized oil production.

Demand for safe assets remains strong because of uncertainty caused by monetary and fiscal policy worldwide. How low in interest rates can we go? How high can CB balance sheet expansion go? How high can credit growth go before there is little material effect on GDP growth? Will the government step out of the way for business creation? How will demographics alter growth moving forward? Will productivity increases save the day? Will taxes go up or down? Will governmental entitlements be cut or eliminated?

Uncertainty is definitely fueling the demand for safe assets.

Everyone seems to think that central banks' QE efforts have "fueled" growth. But how does this square with the fact that 1) QE programs have been orders of magnitude greater than anything central banks have done before, yet 2) economic growth has been weaker than ever before, 3) inflation remains very low in every major economy (if we had had a lot of money printing we should have seen a lot of inflation), and 4) the dollar (where QE has been the most aggressive) is been the strongest of the major currencies (lots of money printing should have weakened the dollar)?

The only answer that conforms with the facts: QE was NOT money printing; QE simply transformed notes and bonds into T-bill equivalents, which were necessary to support huge demand for safe assets. And it is always the case that monetary policy can only facilitate growth, not create growth.

I think it makes more sense to say that QE only facilitated growth, that growth happened in spite of increased uncertainty, in spite of the increased marginal tax rates, and in spite of the increased regulatory burdens. Lingering uncertainty, as you note, is still fueling demand for safe assets.

charlatanisms: earnings yield. contained. and the decline in earnings is only the oil patch (ignoring the flattering of earnings from lower oil). conclusion first, then go find the support. sophism.

Scott: the Bank of Japan has been more aggressive in QE than the Federal Reserve Board. And indeed the yen has fallen against the dollar from about 80 to 120, and then gained to 112-113 recently.

But even the recent yen rise against the dollar appear to be the result of a capital flight to safe haven or quality in Japanese bonds.

Assuming Donald Trump becomes president, we should all prepare ourselves for tariff wars between the US, China, Mexico, and OPEC. I am not a fan of tariffs, but I would say the tariffs Donald Trump has in mind would be a boon for domestic energy and manufacturing. Yes, Trump may not appeal to everyone, but the reality of the anti-establishment movement is likely to result in tariffs that will drive domestic investment, price flexibility, and ultimately earnings in the energy and manufacturing sectors. Said another way, domestic energy and manufacturing stocks may be a real bargain right now...

PS: A 45% tariff against the import of consumer electronics, crude, and automobiles would change the investment landscape in the US. The tariff would probably mean the end of US borrowing from these countries as well, which would mean a balanced budget and savage cuts in government spending -- we should all think ahead...

I'm not willing to make that assumption.

A huge tariff on imports would be very bad for the U.S. economy. Period. I seriously doubt that 1) Trump would actually propose this and 2) even if he did, that it would pass Congressional muster.

Let's consider instead a Cruz presidency and its meaning for investors. What does a Cruz presidency portend for the US economy? I'll have to think that through a bit...

Post a Comment