Real GDP declined for two quarters straight, and most would agree that meets at least one condition for a recession call. I would prefer to call it a Recession Lite.

Over the course of the first six months of the year, real GDP declined by 0.63%. On an annualized basis, that works out to -1.25%, which by the standards of past GDP revisions (which can easily be on the order of ±1-2%), is arguably statistically insignificant. But it does seem clear that the economy is in a bit of a funk, most likely due to high inflation, so it would be fair to say we are (once again) experiencing Stagflation.

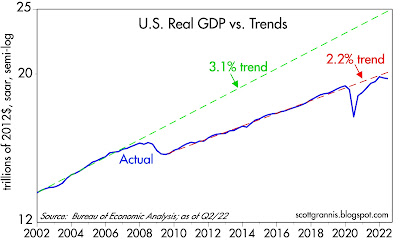

Chart #1

Chart #1 is my contribution to understanding what's going on with the economy. I don't think you'll see this anywhere else. Let me first note that the y-axis is logarithmic, which makes steady growth rates look like a straight line. The blue line is inflation-adjusted GDP, in 2012 dollars (the dollar was worth about 22% more back then than it is now). The green line shows what the path of GDP would have been if the 40-yr trend from 1966 through 2007 were still in place (during which period the economy grew on average about 3.1% per year). The red line shows the 2.2% annual trend which has held since mid-2009.

Today the economy is only about 2.2% below its most recent trend, but it is a gigantic 26% below its long-term trend. The big question we should be asking is why the economy is so far below a trend that persisted for 40 years and which suddenly disappeared following the Great Recession. Demographics likely played a role (an aging population), and globalization likely resulted in the export of lots of traditional jobs to other countries. But those factors don't change overnight—they change over many years. So I'm more inclined to point the finger at politics: increased regulatory burdens, huge deficit spending, and rising tax burdens, all of which create headwinds to growth.

In any event, this year's modestly disappointing economic growth hardly justifies dramatic changes in policy. Since the inflation we are suffering today has its roots almost exclusively in massive deficit spending in 2020 and 2021, the last thing Congress should do is spend more money that must be borrowed (or, perish the thought, printed). And since incentives to work, invest, and take risk are the lifeblood of productivity, the last thing Congress should do is raise taxes on anyone, since higher taxes reduce the incentives to work, invest, and take risk. And since any good economist knows that businesses don't pay taxes, Congress should not even consider raising the corporate income tax rate. If a business is taxed more it must pass the tax burden on to its shareholders, employees, and customers—otherwise it will go out of business. Taxing business is just an indirect—and very inefficient—way of taxing everyone.

Joe Manchin, are you listening? That deal you just signed on to violates economic reason.

Recession Lite seems like an apt descriptor for today's economy, because a lot of the ingredients of a true, painful recession are missing. Jobs are growing by leaps and bounds (about 400K per month so far this year!), job losses are low, job openings are at stratospheric levels, industrial production is rising, capital spending is rising, the volume of world trade is at a new high, the stock market is recovering, and Covid-19 is yesterday's news.

31 comments:

I have preferred the term "recessionette" since 1990 and 2000/2001. That was when the "great moderation" was all the rage and the "experts" thought that the Fed had all the buttons and levers to avert deep recessions.

I recall the dread I had at the end of the 2000/2001 recession. I knew that the pain from at least one and maybe two business cycles had been only delayed. It festered and we got the Great Recession. Even the Great Recession papered over the big time bomb of all the debt in the world. I do not know how that gets resolved. Probably freezing a bunch of benefits in the long term commitments, i.e. pensions- private, state, federal- especially Social Security.

I would like to have a recession where the true excesses of the previous cycles were beaten out of the big risk takers.

The economy since 2008 has resembled Japan, but only a bit. It's also possible we get decades of "no significant growth" in the economy because of all of this nonsense.

The Fed might get its 2% inflation wish for many years- with a O.2% average GDP growth to go along with it.

There is much more potential in our economy and people.

Suggestion humbly based just on arithmetic.

1. slow down the fed funds hikes

2. increase rate of balance sheet reduction by the fed

3.---> hoping that the 2 year might top out about 2.5% and the 10yr might be 3.5%

4. 30 fixed mortgage rates seem to have over-shot, so they might settle at about 5.5%

A softer landing might be achieved by this...

Again, just simple arithmetic. I am not a banker.

Great blog, great post! Thanks.

Yeah, I wonder that that crimp in the graph at 2008 also. Sure, the Great Recession, but then?

Obama became president, but he was sort of another Clinton. Not great, but Wall Street, Silicon Valley, entertainment and the multinationals loved him.

Local governments have just about snuffed out development in places like California and New York.

It is possible that central banks were too tight after 2008, hence the sub-target inflation rates in places like the US and Japan.

Australia's Reserve Board has a 2% to 3% inflation target band, and I always liked that idea.

My take is governments have to be generally pro-business or things begin to stagnate. Endless foreign wars are a drag too.

Economists just don't get it. Banks are not intermediary financial institutions. Bankrupt-u-Bernanke, e.g., introduced the payment of interest on interbank demand deposits (at a level higher than the general level of short-term interest rates - which was illegal per the FRSSA of 2006).

The result was a $6.2 trillion dollar drop in the nonbanks' liabilities, while the banks were unaffected, increasing by $3.6 trillion dollars. I.e., the remuneration of interbank demand deposits inverted the retail and wholesale funding yield curve for up to two years out.

I.e., the remuneration rate induced nonbank disintermediation, an outflow of funds, or negative cash flow.

Then the FDIC insured transaction deposits to unlimited, but reduced them to $250,000 in Dec. 2012 (which caused the "taper tantrum").

Banks don't lend deposits, deposits are the result of lending. All bank-held savings are frozen. This is the cause of secular stagnation.

People don’t have an historical clue. Lending by the DFIs is inflationary (where S “≠” I). Whereas lending by the nonbanks is non-inflationary (where S = I), ceteris paribus.

The ABA got jealous of the S&Ls, etc.

Reg. Q ceilings were gradually eliminated.

The nonbanks were turned into banks.

Interbank demand deposits were remunerated.

Legal reserves were gradually eliminated.

The recipe was the fallacious Gurley-Shaw thesis.

“substitutability between money and wide range of financial assets, also called near- moneys”

“an appropriate definition of money must include the liabilities of non-bank financial institutions.”

R * revolves around the activation of monetary savings. The impoundment of monetary savings lowers R * and vice versa.

Jerome Powell doesn’t have a clue. He has destroyed deposit classifications and overstated deposit volumes.

If banks were intermediaries, we wouldn’t have this problem.

Princeton Professor Dr. Lester V. Chandler, Ph.D., Economics Yale, theoretical explanation was: 1961 – “that monetary policy has as an objective a certain level of spending for gDp, and that a growth in time (savings) deposits involves a decrease in the demand for money balances, and that this shift will be reflected in an offsetting increase in the velocity of demand deposits, DDs.”

Thus, the saturation of DD Vt (end game) according to Corwin D. Edwards, professor of economics. [Edwards attended Oxford University in England on a Rhodes scholarship and earned a doctorate in economics at Cornell University. He spent a year teaching at Cambridge University in England in 1932. He taught at New York University in 1954, the Chicago School from 1955-1963, the University of Virginia, and the University of Oregon from 1963-1971.]

Edwards: “It seems to be quite obvious that over time the “demand for money” cannot continue to shift to the left as people buildup their savings deposits; if it did, the time would come when there would be no demand for money at all”

Chandler’s conjecture was correct from 1961 up until 1981. The S-Curve” hybrid dynamic damage (sigmoid function) in money velocity, was completed by the first half of 1981 (the "monetization of time deposits).

Professor emeritus Leland James Pritchard (Ph.D., Chicago Economics 1933, M.S. Statistics) never minced his words, and in May 1980 pontificated that:

“The Depository Institutions Monetary Control Act will have a pronounced effect in reducing money velocity”.

Why? In short, because banks don’t loan out deposits. Deposits are the result of lending. All bank-held savings are lost to both consumption and investment, indeed to any type of payment or expenditure.

Your question on the natural rate of growth of the economy is interesting. If we take China as an example, we all agree that for several years a rate of 10% per annum was the "natural rate of growth". In the case of China, underinvestment for decades explains the catch-up. Nobody today would think that a 10% GDP growth is reasonable for China -- it has more than caught up (it's around 6% now).

GDP growth has to be based on two things, increased productivity, and population growth that has the same characteristics as in the past. America's population growth for the past 5 years has been less than 1% (in fact below 0.5%). In addition, the composition of the population has changed.

For a long time, America confused off-shoring with an increase in productivity. Now America is beginning to see the opposite trend; offshoring is no longer feasible (and possibly desirable) and population growth is not about to change, first birth rates are falling and immigration is also falling due to the policies of all administrations for the past 15 years (even under Obama). It peaked most recently in 2006, but the trend has been negative.

Again, not saying it's a bad or a good thing, but on-shoring for supply security purposes, lower immigration and low birth rate are all input in the natural rate of GDP growth.

Seriously, a very interesting question; what is the natural rate of growth for America's GDP?

The Chart #1 is fascinating. As a suggested enhancement: could you re-plot the chart with the Y-axis as GDP divided by working age population? This would be a variation on GDP/capita but would tease out the boomer retirements. Or if there is a way to calculate GDP per employed adult, that might tell a different story than the aggregate GDP does. Or maybe not, but I think it would be interesting to know how much population growth/decline plays a factor.

Any chance Manchin will run for POTUS?

"what is the natural rate of growth for America's GDP?"

Tough question.

An easier answer is the clear developing trend of lower growth and productivity due to population aging and debt growth and thereby lower 'natural' rates of growth.

It's bewildering to see the collective drive for more debt to solve issues as population aging requires more productivity for the residual in the working age group.

One way to improve, as a group, would be to try to maintain health and productivity levels with aging. The Covid episode showed many things (difficulty in establishing constructive collaboration etc etc) but it also showed how the US (and other developed countries) is quite sick as a population.

Since the beginning of 2022, a very high number of 'workers' went back to work and net output decreased. Think about that for a minute when analyzing this 'recovery' as, just a few months ago, the economy was felt to be "red-hot" and as it is felt now that the recession will be "lite"?

The unemployment rate is always going to be “too low”. See: “The Great Demographic Reversal” by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan.

But secular stagnation is the deceleration in velocity stemming from the impoundment and ensconcing of monetary savings (beginning in 1981). Contrary to the morons of this world, banks don't lend deposits, deposits are the result of lending. All bank-held savings are unused and unspent.

Jerome Powell thinks banks are financial intermediaries:

https://www.bis.org/review/r170309b.pdf

Scott, in your post from 7/26 you wrote in re the expansion of the money supply: “Fed policy did not create it; massive fiscal deficits did. And since those deficits have all but disappeared, the money supply is coming back to earth.” I commented a few weeks back on this, but think it is important again to repeat the warning with Manchin reverting to form and the two new bills (chips + climate-health) totaling nearly $1 trillion in new spending (the layouts come first, new offsetting taxes down the road): $14.5 trillion in deficits between now and 2031 according to CBO. So my question to you is do you see any reason to doubt CBO’s forecast, or do you think that M2 will not expand again above its pre-pandemic trend line to fund our ever-growing fiscal recklessness?

Jon: the evidence is pretty clear that the Covid-related "stimulus" checks (totaling 4-5 trillion dollars) were somehow monetized and thus became the fuel for rising inflation (i.e., the checks represented newly-minted money). The same does not hold for fiscal deficits prior to Covid, however. But do I worry that another round of deficit-funded spending could end up pushing inflation higher. What remains a mystery, though, is exactly how all those stimulus checks were monetized. Creating M2-type money has traditionally been limited to banks engaged in net new lending, but I can't connect the dots on this for 2020-2021.

Scott, according to GAO, “The federal government made direct payments to individuals totaling $931 billion to help with COVID-19” but I assume you are referring not just to stimulus checks but the entire panoply of covid-relief spending. In any event, here’s my concern: in the 9 years preceding the pandemic, the deficits totaled $6.997 T, averaging out to $777.4 B/yr. But in the next 9 yrs, the deficits will total $14.5 T, or $1.6 T/yr. If so, there will be enormous pressure on the Fed to keep accommodative. Yes, they’ve stopped growing M2 for now, but that can change quickly — especially if the Fed believes they need to finance Congress’s trillion-plus growing deficits, not least of which is their concern about keeping interest payments on the debt swamping virtually all other federal spending. So it seems to me that M2 growth will have to ramp up again beyond the pre-pandemic trend line.

Frozen / Carl - thoughtful comments - thanks. The comment about confusing productivity with lower costs from off shoring, and how that looks in reverse seem right on.

Data point: Here in SoCal, the real estate market has gone into hibernation. Wife kitteh is currently trying to sell a friend's condo in a very attractive location. Two months ago, it would have seen a bidding war after the first weekend on the market. Now, it's been on the market for almost a month, almost no showings and no bids. Other realtors are reporting the same.

Scott your point in cash injection creating inflation. OK yes maybe but does it mean that the additional cash injected into the US Economy created inflation on the whole planet? I mean sure, I am Canadian, I get that you export your inflation to us, but in Europe too.

There's something wrong with your argument, I think, it takes too little account of the ROW. But again, maybe everyone else did the same (BTW they didn't in Mexico and they have huge inflationary pressures -- far worse than the USA.

" OK yes maybe but does it mean that the additional cash injected into the US Economy created inflation on the whole planet?"

Global markets in various items means that ~local inflation gets globalized. For example, many broad commodity indices have more than TRIPLED since their 2020 recession lows. That's a spectacular addition to inflation.

Remember that prices change by the marginal/most recent buyer. Also, be aware that one region having a supply shortage can drive the whole global market price, e.g. if Europe has a Nat Gas supply deficit, the North American price will be spiked higher because those supplies will be redirected to use in Europe.

Many commodities can be significantly impacted by one supplier (or buyer) because many of these markets have few suppliers and buyers. (e.g. a lot of monopoly-like action).

Recall what happened ~5-10 years ago? OPEC continued to increase supply into a low priced oil market to try to drive frackers with expensive cost structures out of business (by lower and lower prices)- just so we could have what we have today- a slight under-supply, and higher oil prices.

Frozen, re whether US money growth created inflation everywhere. It didn't. A quick check of Eurozone M2, UK M2, Japan M2, and Canada M2 shows that M2 grew at an unusually rapid pace in all of these economies, beginning in the second quarter of 2020 and lasting for at least a year. The US wasn't the only government trying to make up for economic shutdowns by flooding their economy with extra money (ostensibly to boost demand).

As for Mexico, its money supply has been increasing at double digit rates for years, so it's not surprising they have high inflation. Nevertheless, I note that Mexico's M2 money supply has increased by 40% since the end of March 2020.

Scott-

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/understanding-bank-deposit-growth-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-20220603.htm

Well, this is what they say.

"Well, this is what they say."

What do you mean by "this" and "they"?

The "note" is simply a simple presentation of basic numbers without ideological or political interpretation?

Carl-

I dunno. Just what the Fed says. They didn't run it by me before publishing.

What do you think of it?

Thanks Benjamin for that link. It does a fairly good job of describing how M2 grew by such an enormous amount. It is also consistent with my concerns (which began in late 2020 and intensified in mid-2021) that the huge increase in M2 had lots of inflationary potential. In short, M2 grew because the public's demand for money surged in the wake of the Covid-era panic. But since the end of 2021, the demand for money has declined since the public's concerns over Covid have also declined. People are spending down their unwanted money balances, and that has fueled a surge of demand and higher prices for a wide range of goods and services.

Fortunately, this process has become less intense and I'm pretty sure inflationary pressures peaked earlier this year as a result. It was all a one-time event which is passing. It was not a massive error on the part of the Fed; that's why the dollar remains strong and gold has failed to rise.

The Fed should be seeing these same things and not panicking. The Fed doesn't need to raise rates much more than they already have. The economy needn't collapse.

Scott-

IMHO, I agree with you.

Government bumbling (or worse) on the C19 situation created a first-class mess. Toss in Ukraine, and some bad luck with OPEC+, the usual government clogging, and you have the present circumstance.

I will say it again: America's large private-sector (public) companies are the best-run large organizations on the planet, maybe in history.

They can prosper through inflation. I hope we can dodge a recession. Ordinary people get hurt in recessions.

^The linked article, in numbers, explain the sources of M2 growth in the last few years. As mentioned several times in the last few months:

-the most important component was QE, which is not a significant factor in consumer inflation

-the second most important factor was the accelerating commercial banks' intake of government-debt securities (printing a deposit and effectively financing the Treasury, MMT-style)

-the last component was, overall, relatively low loan and leases growth

-----

The MMT-style event has come to an end but could come back with more bipartisan failure.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USGSEC

Note that the MMT-style event has happened since the GFC (like the linked article also demonstrates) but the inflationary impetus was masked and overridden by secular deflationary forces then before the Covid massive acceleration.

The MMT-style event has resulted in a huge increase in the levels of checkable deposits and this explains (mostly and on top of supply-chain related constraints which are being cleared; with about a 12-month lag) the rise in inflation recently seen.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGZ1FL193020005Q#0

-----

There have been changes in savings behavior including large movements of money to money market funds (without which the rise in commercial banks' deposits would have been even more spectacular) but (as Salmo Trutta keeps mentioning) even if the RRP operations effectively reduce M2 and deposits, this is not recorded as such due to the 'temporary' accounting definition.

Anyways. The concept of precautionary savings and money demand in order to explain the rise in deposits, as explained, is flawed. Once money is 'created' through QE or MMT-style events, it largely remains within the system and, apart from the MMF component described, money stays essentially within the commercial banks' system. Let's say Scott decides to spend, this will lower the bank account balance but it will ($ for $) raise Benjamin's bank account. In the aggregate, people don't decide the level of deposits in the system. For the last few years, QE and MMT-style events do. People no longer influence money supply through hoarding (mattresses, safety vaults etc).

-----

A conceptual way to complement understanding is to look at the loan to deposit ratios across banks. With the modern Fed-Treasury cooperation, the deposit part has increased and the main-street loan part has remained a marginal factor (Japan has been going through this for more than 20 years).

https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/us-banks-see-decrease-in-q1-loan-to-deposit-ratio-yoy-70569360

A fascinating aspect is that the growth (real growth) of all credit at commercial banks is becoming negative, a very unusual development, especially if you expect robust growth in a tightening phase and an amazing inverted curve environment.

I took a long road trip last week, and stopped in a small midwestern town.

I looked it up and it had lost about 25% of its population (~3000) in the past 40 years.

I went into three businesses and two of the three appeared to either have AC problems or they were purposely not cooling all of the building due to the high cost. I am pretty sure at least one of them was purposely keeping the AC off in areas of the building.

In addition, the average person certainly did not look "very well off".

It was unfortunately stagflation and globalization on full display.

re: "A fascinating aspect is that the growth (real growth) of all credit at commercial banks is becoming negative"

No, that was predictable. The welfare of the banks is dependent on the welfare of the nonbanks. The pundits think banks are intermediaries. That's why the FED eliminated reserve requirements, eliminated Reg Q ceilings, etc.

Banks don't lend deposits. Deposits are the result of lending. Ergo, all bank-held savings are frozen, lost to both consumption and investment. An increase in bank-held savings shrinks R-gDp. Mr. Grannis refers to this as the "demand for money".

Japan is a perfect example. “Japanese households have 52% of their money in currency & deposits, vs 35% for people in the Eurozone and 14% for the US.”

Dr. Philip George refers to this as "The Riddle of Money Finally Solved" (Alfred Marshalls: "cash balances" approach). Dr. Leland Pritchard said the same thing more than 30 years earlier in IMTRAC.

To avert a recession, you lower FDIC deposit insurance back to $100,000, and simultaneously drain the money stock.

From the standpoint of the system, and not an individual bank, the commercial banks do not loan any existing deposits, demand or time; nor do they loan out the equity of their owners, nor the proceeds from the sale of capital notes or debentures or any other type of security.

It is absolutely false to speak of the commercial banks as financial intermediaries not only because they are capable of “creating credit” but also because all savings held in the commercial banks originate within the banking system.

A great many Americans are about to lose everything...

Hello Salmo Trutta:

I love reading you comments, even if, as I am not an economist, I need to re-read and go to your references to better understand.

Can I ask if you could, uhh .. in laymen terms, say exactly why you think inflation/interest rates have remained so low - until recently, despite the huge increase in Fed balance sheet/reserves over the last 13 years. I know you believe the money has been locked up in banks, and not lent out. But why have the banks not been loaning? Or why is there not the demand for loans?

Alternatively, are low interest rates also a result of simply increased productivity from technology over the last 20 years? Even if the productivity figures do not show up in studies from various organizations that calculate such things, it is hard to imagine that technology has not immensely increased productivity.

Thank you,

Richard

Post a Comment