It's no secret that virtually every recession in the past 50 years (with the exception of the brief economic collapse of last year) was triggered by the Fed tightening monetary policy in order to bring inflation down. That explains why the equity market is reeling: the market believes that today's unexpectedly high inflation will provoke a serious Fed tightening which would inevitably pose a serious threat to the economy.

But even though inflation is much higher than nearly everyone expected (with the exception of economists such as Steve Hanke, John Cochrane, Brian Wesbury, Ed Yardeni, and Bill Dudley and yours truly), a recession is not inevitable this time around, for two very solid reasons: 1) the current bout of inflation was triggered by runaway federal spending that was monetized by the banking system, and that inflation source has all but dried up, and 2) the way the Fed is tightening monetary policy today is very different from how it worked before 2008, and much less likely to harm the economy.

In my last post, I discussed how the evidence shows that enormous federal deficits resulting from Covid-related "stimulus" spending were monetized, resulting in an unprecedented increase in spendable money (M2) held by the public. In earlier posts I've discussed how the the tremendous uncertainties surrounding the Covid-related economic shutdowns boosted the demand for money, and how this delayed the onset of inflation by about a year. Inflation didn't start rising until a year after M2 started surging and until it became clear that the Covid threat was receding. Five weeks ago I explained how money demand was likely to start falling, and how this could result in a surge of retail demand (and continued high inflation) over the next year or so.

We now know that federal deficits have collapsed (because spending has collapsed and revenues have surged) and M2 growth has also collapsed. In fact, M2 grew at a very slow 1.3% annualized pace in the most recent 3 month period, and in April of this year it actually declined from its March level. This effectively removes a major source of future inflation potential going forward, thus making the Fed's inflation-fighting job a lot easier.

It's instructive here to recall how the great inflation of the 1970s was created. It began with the Nixon administration's 1971 decision to abandon the dollar's peg to gold, which in turn sparked a massive loss of confidence in the dollar that took 10 years to run its course. The devaluation of the dollar reduced the world's demand for dollars, and it was excess dollars being unloaded that fueled a decade of painfully high inflation. M2 grew at a rapid pace (8-10% per year) throughout those 10 years, so it's not surprising that it took Volcker about 4 years and two recessions before he could bring inflation down. Nothing like that is happening today.

Federal deficits have plunged, and are likely to remain relatively low and non-threatening for the foreseeable future. With his approval ratings nearing rock bottom, Biden hardly commands enough power to push through more spending bills, and meanwhile there is a growing awareness that past spending sprees are responsible for today's inflation. If Congress can simply stop spending more, economic growth and inflation will continue to boost federal revenues. Ongoing inflation will also erode the burden of all the federal debt that has been incurred in recent years. Doing nothing and allowing time to pass will go a long way to bailing us out. Unfortunately, there will be a cost to all this, and it will be borne mainly by the middle class as real incomes decline.

Prior to 2008, the Fed tightened monetary policy by draining bank reserves, which in turn created a liquidity shortage and forced short-term interest rates to rise, since banks needed to compete for scarce reserves by paying more for borrowed reserves to support their deposit base. In the latter stages of Fed tightening, very high real interest rates and scarce liquidity triggered bankruptcies and generally depressed economic activity—until the Fed realized that tight money was no longer needed. It's a sad story often told, but it won't necessarily be repeated.

Today, the Fed doesn't need to drain bank reserves, even though they are super-abundant (currently $3.3 trillion, an order of magnitude larger than required) and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. Because the Fed now pays interest on reserves, it can tighten monetary conditions simply by raising the rate in pays on reserves, since that effectively sets a higher floor on all other interest rates. Higher interest rates have the added benefit of increasing the public's demand for M2 money (by making bank deposits more attractive and borrowing less attractive), thus limiting the inflationary potential of all the excess M2 that is sloshing around. With no need to drain reserves, we are unlikely to see threatening liquidity shortages.

Meanwhile, the dollar is strong, inflation expectations are subdued, and excess M2 is declining. All of which reinforces the idea there is light at the end of this inflation tunnel. The situation is far from being out of control.

Nevertheless, we should expect to see uncomfortably high inflation for another year or so. The huge increase in housing prices in recent years will take at least that long to find its way into Owner's Equivalent Rent, an important component of the CPI, and it will take time for excess M2 to unwind. And meanwhile, supply-chains are still in disarray, and geopolitical tensions are working to boost energy and raw materials prices.

As Chart #12 suggests, the current level of the 5-yr TIPS real yield is consistent with real economic growth of about 2%. In other words, the bond market expects the economy will grow at a moderate 2% pace for the foreseeable future. This is somewhat slower than the 2.2% annual pace that the economy managed from 2009 to just before the Covid crisis hit. There is every reason to think the economy will continue to grow: job openings far exceed the number of people looking for a job, and there are still millions of workers who are sidelined currently but potentially available to rejoin the workforce. Meanwhile, business investment (e.g., capital goods expenditures) is stronger than it has been for decades.

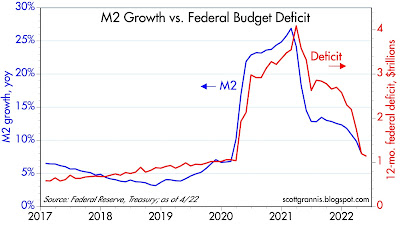

Chart #1

Chart #1 is an update of Chart #3 in my last post. The federal deficit over the past 12 months has declined to $1.1 trillion, which is WAY down from its high of over $4 trillion a year ago. Money printing is not likely to recur, and that greatly reduces the future inflation threat we face.

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows the level of M2 and the huge gap that exists today relative to where M2 would be if it had continued its long-term trend growth rate of 6% per year. The vertical dashed line marks the point at which I project the future path of M2 assuming it declines by about 1% every 3 months (in line with the decline that has already occurred in the April M2 data). At this pace the level of M2 would return to "normal" by around the end of next year.

Chart #3

Chart #3 is one I have been showing for many years, since I think it is the best way to visualize the demand for money (think of this as the amount of cash the average person holds as a percent of his or her annual income). Money demand typically rises during recessions, as uncertainty causes people to become more cautious. It typically declines in the wake of recessions, as confidence returns and spending increases—exactly what's been happening over the past year. But as I've mentioned several times in the past, money demand has been extraordinarily high in recent years, and it seems very likely to decline going forward, which is why it's very important that money printing cease and the Fed raises interest rates to offset the decline in money demand. The last data point in the chart (Q2/22) assumes a modest decline in M2 (which is already underway), a modest 2% real growth rate of GDP, and inflation of 7%.

If those assumptions hold, then the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP would fall back to 70% by around the end of next year, which is where it was prior to Covid. A painful round trip, to be sure, but not the end of the world.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows how an increase in housing prices (blue line) takes about 18 months to show up in the Owner's Equivalent Rent component of the CPI (currently, OER is about 30% of the CPI).

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows the rates on 30-yr fixed rate mortgages. Mortgage rates started exploding last February, rising from 3.25% at the end of last year to now almost 6%. Not surprisingly, the number of new mortgage loans originated already has plunged by one-third since February, thanks almost entirely to soaring borrowing costs. This is evidence that Fed tightening has already had a significant impact on the economy—it's already cooling the super-hot housing market. The Fed doesn't need to raise rates so much as it needs to convince the market that rates are going higher, and they have accomplished that already.

Chart #6 shows the current shape of the Treasury yield curve (blue) and what the market expects it to look like at the end of next year (red). The market fully expects the Fed to raise its target funds rate to about 3.5% or so between now and then. Longer-term rates haven't changed much and are not expected to change much going forward.

Chart #7

If there's one thing that is looking pretty bad these days, it's consumer confidence (Chart #7). Confidence is abysmally low, and that owes much to the huge increase in food and gas prices along with disapproval of the Biden administration's handling of things. On the bright side, this lack of confidence is working to keep the demand for money stronger than it otherwise might be, and that lessens the inflationary potential of all the extra M2 out there.

Chart #8

It's also nice to see that credit spreads are not soaring. Chart #8 looks at the "junk spread," which is the difference between investment grade and high-yield debt. Spreads are up, to be sure, but they are nowhere near worrisome levels.

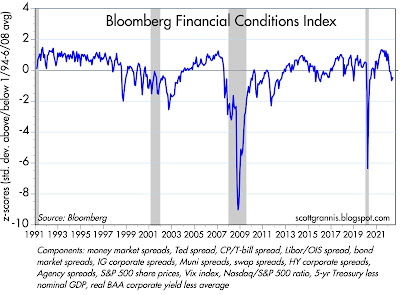

Chart #9

Bloomberg has an index of financial conditions, shown in Chart #9. Here we see the same story: conditions have deteriorated somewhat, but they are far from being worrisome.

Chart #10

Chart #10 shows 5- and 10-yr Treasury yields and the difference between the two, which is the market's expectation for what the CPI will average over the next 5 years. Inflation expectations are up, but they are not out of control—currently about 3.2%.

Chart #11 compares the current level of 5-yr real yields on TIPS (red) with the current real Fed funds rate (blue). The red line is effectively what the market expects the blue line to average over the next 5 years. The Fed is expected to tighten significantly, but from a very accommodative stance to begin with.

Chart #12

Chart #13

Chart #13 shows the Fed's calculation of the real, inflation-adjusted and trade-weighted value of the dollar vis a vis other currencies. That the dollar is so strong these days—despite trillions of dollars of newly minted M2—can only mean that while things could certainly be better here, we are in much better shape than the rest of the world. All central banks have been ultra-accommodative, but the dollar and the US economy are the best safe-havens given today's geopolitical turmoil.

-----------

There is definitely light at the end of the inflation tunnel (though it's about a year long), and there is little reason to think that Fed tightening—which has already had a significant impact—will be as much of a threat to the economy as past tightenings have been. With one major caveat: Congress must resist Biden's pleas for more taxes and more spending. More taxes would weaken the economy and more spending would aggravate inflation pressures, but neither seem very likely in my judgment.

66 comments:

the smiths will have to record a follow up to "bigmouth strikes again" with "pangloss strikes again". cork the cheerleading and be humble in the face of the pain many are experiencing.

I believe what you say about the economy. But this scenario is bearish for equity markets. The rise in long term rates, which I think is permanent, is terribly for growth, and growth is (was) most of the market. A lot of growth/venture/angel investors are screwed, and may be out of the market for awhile.

I agree that the credit spread is not high but that's because treasury yields are way up-currently over 3% on the ten year. That treasuries are falling (yields rising) while stocks are falling is VERY worrisome.

Scott I always enjoy you commentary and the accompanying detail. You are far more optimistic than other that I follow, in particular there is no mention of the bow wave of debt we are pushing and how it may be resolved. Sure, inflation does it work in real terms but we will need inflation in the low double digits for a decade to get the debt/GDP back in 70-75% range. That means the FED's balance sheet will have to expand since they will be one of the few buyers on the street. I worry we may find ourselves in a debt spiral.

Jim

Scott,

As usual enjoy your analysis. Could you answer two questions as a follow up? 1. The rest of the world has similar debt and inflation problems. How will they be effected by the Fed’s actions. 2. The congress and President over the last few years have resorted to spending stimulus whenever the public has had financial stress. What are your thoughts on the odds of that happening in the next year?

Your analyses are exceptional. Your "demand for money" is fascinating. It shows that income velocity is fictitious. It explains the 4th qtr. 2021 surge in N-gDp @14.5%.

The 1970's inflation was driven by several factors, the growth of the E-$ market, the pegging of interest rates during the monetization of time deposits (the un-gating of commercial bank savings deposits and transition from clerical processing to electronic processing), and the acceleration in money stock growth.

But some pundits are re-writing history:

https://www.realclearmarkets.com/articles/2022/06/03/monetary_policy_is_all_talk_all_the_time_and_always_has_been_835544.html

Even Alt-M gets it wrong: "they therefore entail financial intermediation in which the depositor can be thought to lend cash to the bank, which then relends part or all of it"

https://www.alt-m.org/2015/11/07/monetary-base-total-reserves-fed-confusions-misreporting/

"Canada, the UK, New Zealand, Australia, Sweden and Hong Kong[13] have no reserve requirements...This does not mean that banks can—even in theory—create money without limit. On the contrary, banks are constrained by capital requirements"

Thank you Scott for your continued analysis and contributions. They are very much needed in today's markets. Long time follower here, thank you!

Tightening always produces unanticipated naked swimmers. My guess is a crpyto collapse taking overleveraged participants with it. Yes interest rates are impacting securities markets but the current downdrafts aren't about an impending recession but rather shadow banks forced liquidations because of crypto as illquid collapsing markets find margin calls being met with liquid market sales. The only issue is the banking sector's exposure to those participants and in their own trading accounts. The real unknown is what new instruments the algorithmic geniuses have created to arbitrage the differentials or to give the appearance of offloading risk.

I pretty much have given up on all other financial blogs and "news." Thank you for your generous sharing of your expertise, data and insights. It keeps my plan on track during the rough rides.

"...Steve Hanke, John Cochrane, Brian Wesbury, Ed Yardeni, and Bill Dudley and Scott Grannis!"

The summer reading list is now a pile-high, solid stack!

Can the central bank withstand the pressure and let inflation run that high for another year? I doubt it. CBs are cornered.

you say "...inflation expectations are subdued..."

6/12/22 WSJ: "...consumers’ longer-term inflation expectations rose to a new 14-year high...: https://www.wsj.com/articles/sizzling-prices-complicate-feds-inflation-fighting-strategy-11655026200?mod=hp_lead_pos3

so which is it?

Most companies hired way more than they need, now they are laying off, this will gain momentum going forward.

Fed's looking backwards.

One reason why credit cards balance sky rose substantially last couple of months, people remember that when time are tough, credit disappear.

We'll get a nasty recession.

Another excellent wrap-up by Scott Grannis.

I sure hope SG is right.

Looks like the GOP will win the Congress come November, so whether for better or worse, Biden is finished making macroeconomic policy. It will be Congress and the Fed.

The US looks bad right now, and the polarization in the US is terrible. But if you lived through the 1970s, inflation was even higher, and it looked like US cities were dying, and crime was running out of control. The US convulsively left Vietnam, in the wake of 60,000+ dead US soldiers and millions of SE Asians. People had bad hairdos (though no facial tattoos or nose rings).

The 2020s look ugly so far, but maybe better times ahead.

Good luck everybody.

Re which is it? (inflation expectations are subdued vs inflation expectations rose). Both are true. 5-yr inflation expectations are 3.12%, which is quite high relative to where those expectations have been over the past 25 years, but actual inflation is much higher (8.5%) than it has been in many decades.

Re crypto collapse underway: Somewhere in my comments to a post or posts in recent months I think I said that what most worried me was a crypto collapse. Seems like that is underway, and it is creating shockwaves all over. No one knows what the eventual impact of this could be, and that's true uncertainty. The stock market hates true uncertainty. Unlike recessions and their consequences, the Fed has little or no ability to bail out cryptos. If I have done one smart trade in the past several years, it was to never touch crypto currencies. Crypto has always been pure speculation in my mind.

Scott,

Thanks for compiling and sharing this information. I stop here for every update. However, I'm going to disagree with your conclusions in this case.

I believe that you miss a key factor driving the economy into recession (over the cliff?) - government regulation. The executive branch is busy throwing regulations onto every facet of the economy. The cumulative effect will be to generate a recession far deeper and longer than what we would expect based solely on Fed tightening. In addition, most blue states are busily growing their own regulatory mess, even as they lag untangling their insane Covid regulations. Given that the blue states still generate a majority of GDP, their cumulative regulatory behavior has a significant impact. Even the Republicans taking Congress this fall will have little impact. Hundreds of thousands of bureaucrats can manage to escape legislative oversight pretty easily, and they still have a lot of sympathetic ears in the judiciary. Bottom line, I expect the worst recession in my lifetime and since I'm 70, I've seen a lot.

John, re regulatory burdens: I have no doubt whatsoever that government regulation is very bad for the economy. I've been lamenting increasing regulatory burdens ever since I started this blog back in Sep. '08. For most of the Obama administration I thought that increased regulatory burdens would add up to sub-par growth. I still think the economy's growth potential has been seriously reduced because of regulatory burdens, and as you note, the outlook has not improved.

However, I doubt that regulatory burdens are going to increase by enough to engineer a recession. Sluggish growth for sure, but not outright recession. We've been enduring egregious regulatory burdens for a long time, and the result has been felt in sub-par growth. Trend growth prior to 2007 was 3.1% per year, and since then it has been about 2.1%. 1% less growth for 15 years adds up to trillions of dollars of living standards down the toilet. It's a shame, but it's not necessarily the end of the world

One small but encouraging fact: the number of public sector jobs today (22.3 million) is the same as it was in late 2007. That means that the ratio of public sector workers to private sector workers has declined by about 10% over the past 15 years.

Thank you for the thoughtful piece Scott, I appreciate your insight. My only issue is your chart of HY/junk spreads: HY OAS as of Friday 6/10 was ~450 bps (and higher yet today), not the ~250 bps shown in your chart. So, risk in that corner of the bond market is indeed elevated, although not to flashing-red levels.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BAMLH0A0HYM2

Thanks for the forum.

Re. the Fed now paying interest on reserves - what a nice trick.

When you can't move interest rates anymore because you've plowed so many reserves into the system - and too big a risk to drain them - bingo - lets just get around that by paying interest on those reserves. The more we pay, the more you (banks) can borrow at something less than that. If the Fed wants to pay me (bank) 1%, I will do whatever I can to borrow at 3/4%. The higher the interest rate, presumably the higher the spread.

How is this interest going to be paid (taxpayer/saver)?

This is so circular and perverse.

I have one unrelated question to anyone who knows the answer .. why is 2% inflation the holy grail? I can never find an explanation. Why should it not be zero? Or negative, reflecting productivity? (I have never bought arguments that people delay purchases a year! because the dollar will be worth 2 or 3% more the next year.) I know in a depression no one wants to buy anything anyway, but that is not an example of normal productivity deflation.

Thank you in advance. Richard

Unknown, re credit spreads: Chart #8, to which you refer, represents the difference (i.e., the "junk spread") between HY spreads (450 bps) and Investment Grade spreads (140), which difference was 310 bps as of Friday. But yes, it's probably higher today, although the data has yet to be released. I would guess the junk spread is now about 350 bps. Not insignificant, but still quite a bit less than the peak spread (546) we saw in March 2020, at the height of the Covid scare.

Thanks, Scott. Upon further review I saw the difference in data series. Appreciate your work.

Richard, re 2% inflation. I completely agree with you. There is no good reason I'm aware that the ideal rate of inflation is or should be 2%. Zero would be the logical choice for me.

Re the Fed paying interest on reserves. I've discussed this at length starting in 2009. It was certainly a major shift, but there is some logic to it. The main reason the Fed shifted to Quantitative Easing was to address the fact that there was a severe scarcity of risk-free assets in the world that arose in mid-2008. The Fed sold all its T-bill holdings that year in a vain attempt to satisfy the demand for risk-free assets. Then someone at the Fed realized that if the Fed paid interest on reserves, then reserves became functionally equivalent to T-bills. With the demand for T-bill equivalents super-huge, the Fed could then transmogrify Treasury securities in to T-bill equivalents massively and the financial markets would be satisfied. Do a search on "transmogrify" in the search bar (upper left hand corner of my blog) and you will see a whole bunch of posts on the subject.

Of course, as you note, the Fed would start getting squeezed if and when short-term rates (e.g., interest on excess reserves) exceed longer-term rates, because at that point the Fed's portfolio of Treasuries would not generate enough interest to cover the interest the Fed pays on reserves. The Fed itself has worried about that for many years, but it has always seemed to be a problem far in the future. For example, for calendar 2021, the Fed enjoyed a positive spread between IOER and its security holdings of $107 billion, which sum was transferred to Treasury. There may come a day when the spread turns negative, but then Treasury could always bail out the Fed I suppose.

Thank you Scott.

I will look up the "transmogrify" links.

The trick was simpler before; the gov. (treasury) just borrowed, through the banks, from the gov. (fed), and they exchanged some interest. Now the banks are getting much of the interest.

This from an "idea" someone at the fed came up with as a way to create T-bills out of thin air - I did not know that. I once built a card house up 6 levels ..

Amen, on crypto currencies.

Talk about 21st-century witchcraft. Voodoo investing.

I am not even a gold fan, but at least gold is desired as jewelry and ornamentation, and has some legitimate industrial uses.

The risk in gold, art, collectibles is that they are worth what people say they are worth. No income streams. If Andy Warhol goes out of style tomorrow, then your $150 million print becomes worth $5 million (to me, $5).

Crypto is a one cut below even that.

Add on:

The S&P 500 p-e ratio now at 18.95. Still a little rich, but much less rich than other recent eras. The long-term average is 15 and change.

I am surprised not at the recent bear moves, but how strong stocks are. We have a full-on lunatic in Moscow (and maybe Beijing too), governments cratering economies in the unsuccessful fight against C19, and inflation.

Good luck everybody.

We are entering a period when current market data should be read with suspicion. My guess is that the Fed's recent actions to save the economy will fail. Hence, the only way forward that has any chance of saving the dollar and US economy will be to crash the economy through a transitory recession leading to deflation and economic depression. Note that depressions bring much economic hardship, including unemployment and fundamental restructuring of markets and industries. However, depressions tend to shake the 'bad stuff' out the economy in a way that can restore free market capitalism in America. My primary worry is that a depression would somehow result in national socialism (fascism) in Western countries of Europe and the Americas. But again, I believe the Fed's effort to save the dollar and economy will fail leaving only economic depression as the only remaining path forward. I hope I am wrong. In the meantime, be safe out there, every second.

PS: I am long commodities and cryptocurrencies -- no changes in my real estate holdings.

PPS: The US is losing the currency wars...

2% as inflation target- because the powers that be are much more afraid of a little deflation than inflation. Cutting and raising rate tools they have don't work in deflation- or at least differently/not as well.

The Fed actually has some room in their mandates- 5% inflation and 5% unemployment would likely be viewed as a "victory". I think it's possible. Probable? Maybe not.

No offense to anybody.

But cryptocurrencies.

That is called "voodoo investing."

“Mr. Hanke, predicted in these pages (WSJ) last July that year-end inflation for 2021 would “be at least 6% and possibly as high as 9%.”

https://www.wsj.com/articles/powell-printing-money-supply-m2-raises-prices-level-inflation-demand-prediction-wage-stagnation-stagflation-federal-reserve-monetary-policy-11645630424

https://www.wsj.com/articles/money-supply-inflation-friedman-biden-federal-reserve-11626816746?mod=article_inline

“Powell cited 1965, 1984 and 1994 as examples where the FED corrected the economy without a recession.” Interest rates are not the primary determinate of GDP.

link: Daniel L. Thornton, Vice President and Economic Adviser: Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Working Paper Series “Monetary Policy: Why Money Matters and Interest Rates Don’t” bit.ly/1OJ9jhU

Nominal retail sales are down (!) and GDPnow is now at zero for the quarter.

The Fed announces a 0.75% hike and long rates are going down and the curves are inverting.

The Fed is initiating a tightening as stocks and the economy are turning negative and with velocity of money coming down.

This recent inflation episode is living on borrowed time.

There is a lot going on today that connects with Japan in the late 80s.

Retrospectively, it was discovered that their central bank was slow to react to inflation (asset and consumer) and then slow to react to ease during the subsequent downturn.

A humbling aspect (for the observer) is that Fed's actions (if any significant) tend to be associated with long (12-24 months) lags.

It’s not rocket science. The FED’s Ph.Ds. don’t know a credit from a debit. It’s not just theoretical, there’s empirical evidence.

Lending by the banks is inflationary. Lending by the nonbanks is noninflationary, other things equal. The nonbanks are not in competition with the banks. The NBFIs are the DFIs customers. The elimination of Reg. Q ceilings was a huge mistake.

The latest Atlanta GDPnow forecast is zero percent. Raising policy rates disproportionately affects the nonbanks or the velocity of circulation (because of paying interest on reserves). It reduces R-gDp faster than inflation.

Link: REGULATION Q AND THE BEHAVIOR OF SAVINGS AND SMALL TIME DEPOSITS AT COMMERCIAL BANKS AND THE THRIFT INSTITUTIONS by Timothy Q. Cook

https://www.richmondfed.org/~/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/economic_review/1978/pdf/er640602.pdf

The “demand for money” is fickle. It fluctuates more than the money stock. But the FED discontinued the G.6 Bank Debits and Deposit Turnover Release in Sept. 1996 for spurious reasons.

In 1931 a commission was established on Member Bank Reserve Requirements. The commission completed their recommendations after a 7 year inquiry on Feb. 5, 1938. The study was entitled “Member Bank Reserve Requirements — Analysis of Committee Proposal” its 2nd proposal: “Requirements against debits to deposits”

http://bit.ly/1A9bYH1

After a 45 year hiatus, this research paper was “declassified” on March 23, 1983. By the time this paper was “declassified”, Nobel Laureate Dr. Milton Friedman had declared RRs to be a “tax” [sic].

Pre-bell Thursday not pretty

^Yes, the 'narrative' seems to be evolving fast.

The fundamentals are long in the making but fear/greed psychology can turn on a coin.

This title may soon require rewording:

Recession happening need not require much Fed tightening.

Thanks Scott. Excellent write-up.

Assuming Fed ultimately raises FF to about 3.5%, and inflation evolves as you lay out, what would you expect long-term treasuries to be (say) end of next year? Corollary question: Does the Fed have some incentive to accelerate quantitative tightening (selling some of their securities BEFORE they naturally mature), to maintain a positive sloping yield curve? Or perhaps based on one of your comments above, raise FF to less than 3.5%, and do a little accelerated QT ... so as to maintain that positive yield delta on their balance sheet.

(I tentatively disagree with you re crypto. But we shall see;)

Well, I bought in today. It all seemed pretty cheap; not that it can't get cheaper. But a sale is a sale.

Brian Wesbury, explains latest M2 low print, by distortion from tax payments. So that data need to be watched longer term.

I’m late to the game here, but while I agree with much of Scott’s thinking on this, I think he’s too optimistic re future federal spending. While the deficit will fall to $1 trillion in 2022, according to CBO federal deficits will begin rising in 2023 and over the next decade will total $14.5 trillion, more than 6% of GDP by that point. For this reason alone I’m not sure I see inflation being tamed anytime this decade.

@Adam

The distortion from tax payments is real only because most of the unusually high tax payments in April were deposited in the Treasury General Account at the Fed, an accounting event which results in exactly the same thing as quantitative tightening: less reserves, less deposits and...less M2.

Are peaking tax payments a lagging, coincident or leading indicator?

@Mark

Interesting. after moving form QE, qualitative QE, semi-yield curve control (with interest rate caps), now comes active selling of longer dated debt securities to 'control' the slope of the yield curve. The central control of longer-dated rates may prove to be an elusive concept? Isn't the bond market refusing to cooperate at the longer end?

@Jon S.

Fiscal dominance is an issue and one has to hope that, somehow, growth through money printing becomes an idea belonging to the dustbin of history.

If the US proxy war keeps on going and gaining strength as it looks locked in with Lithuania actions today then Depression is very much in the cards. Currency wars and capacity wars are now in play. The fed was behind on inflation long ago as stated here long ago...

this one is going to hurt

Hi, many thanks for your blog. I don't do any macro related investment decisions but despite that it is really useful to have an objective independent opinion on what is going on, always referred to facts.

On this blog entry the doubt I have is that all the inflation component that you talk about is purely monetary. I agree with your logic and views regarding that angle, but I think that part of the inflation is not purely monetary but comes from energy effect on costs. Even the effect in inflation from energy will go back to zero, I don't think it will be go to negative (energy prices to remain high) so that extra cost will gradually transfer to all goods and services traded in the economy bringing more lasting second round inflation.

I understand I might be wrong but would be glad to hear your opinion on why or where I am wrong.

Many thanks, again.

An anecdote to Enrique's point - I'm trying to buy a car to replace one that lost a collision with a deer. I'm told I can order one - and pay a few thousand over sticker, or buy one that's arriving that buyer backed out on for $10,000 over sticker. That's not monetary inflation - that's supply.

For those that think energy prices will remain high- that's another "this time it's different"... it's never really that different. Note that two or three times in the past 30 years, oil prices have been lower than they were in the 1950-1960 time frame.

The reason for high energy prices is mainly from government regulations/costs being put on energy suppliers. I believe about 75% of executive orders since 2021 have been on this industry.

The technology for extracting energy is so much better now than it was in the past energy crisis era (~1973-1983), that just government getting out of the way will solve this part of the inflation problem.

See:

https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart

Enrique, re whether part of today's inflation is due to energy not monetary factors. It's always the case that energy prices can rise (or fall) significantly and that this has an impact on reported inflation (eg., the CPI). Energy prices are an order of magnitude more volatile than prices in general. But rising energy prices by themselves do not create inflation. Inflation is when all or almost all prices rise, and that can only happen if there is monetary accommodation.

If monetary policy is done right, increases in energy prices will result in decreases in other prices. There is only so much money to finance purchases; if you have to pay more at the pump, you have less to spend on other things.

I think both things are happening today. Energy prices have increased because the supply of energy has been reduced. Biden has been anti-oil from the beginning, and the problems in Ukraine have also served to distort the energy market. But at the same time there has been an enormous increase in the amount of money in the banking system, and this allows other prices to rise along with rising energy prices.

More recently, however, we are seeing signs of falling commodity prices and a very strong dollar, both of which are inconsistent with a monetary-led inflation. I'm working on a post to expand on this.

The recession began in January 2022.

We are already in a recession.

From an historical point of view, long-term monetary flows, the volume and velocity of money, are at their highest rate-of-change ever. No other period is even close.

"Inflation is when all or almost all prices rise, and that can only happen if there is monetary accommodation.---Scott Grannis

Well...

George Selgin is an interesting guy, and long story short, he points out (he uses an example of an agriculture economy going through a crop bust) that transactions can drop as prices rise.

MV=PT

A contraction of V or T, and you can get higher P, even if M is held constant. A shrinking economy with higher prices.

IMHO, this happens in the modern US economy when you have increasingly strict property zoning and red tape, and other regulations, pushing down on T and V.

The CPI, as measured, rises, even as the supply of housing (and related transactions) is cut down.

Of course, one could posit in a world of decreasing velocity and transactions, the central bank should reduce the money supply to hold prices constant.

But...that is tricky business. Tightening up on the money supply into a world of decreasing transactions...the Great Depression come to mind.

This is the challenge central banks often face. Of course, see Turkey: At other times central banks are just too expansive.

Maybe the Fed recently too.

Hello, I have a question for anyone who can help. For a long time we have heard that the Fed increases reserves by buying treasuries through the banks (I believe this is correct - that it has to happen through the member banks). My question is where do the member banks get the money to initially buy the treasuries that they sell to the Fed?

This seems important. In other words, assuming a bank has no excess reserves - or additional bank capital - to begin with, where is it going to get the money to help the FED create these excess reserves?

I think I might hazard the answer, which is what I'm afraid of. That the FED allows, for a microsecond, the banks to purchase the treasuries with no excess reserves.

Thank you in advance. Richard

@Unknown

QE is simply an asset swap (Treasury for money).

With open market operations involving what the banks hold on their balance sheets, reserves are created vs the acquired government debt securities and reserves, when created, remain trapped within the financial plumbing (Fed and commercial banks).

We know though (from Flow of Funds and other works), that most open market operations are carried out with a relatively select few non-banks (hedge and pension funds etc) and banks, then, are only intermediates. Then, you get the same balance sheet movements in the plumbing but ALSO you get banks 'printing' a new deposit (money as an asset and money as a deposit liability)in the real world. This results in distorted results for reported aggregates but the functional outcome is simply an asset swap where the pension fund simply switches a security which yielded close to nothing for a money asset yielding nothing.

QE is not tied to consumer inflation in a meaningful way but it's the associated facilitation of non-productive issue of government debt that is the fiscal QE that Selgin refers to.

-----

Numbers reveal a clear downturn in manufacturing and services are not picking up the slack as Fed-Treasury support becomes a drag. Forward-looking indicators for services are not looking good. It's not a matter of if, it's more a matter of how long/deep etc. It feels like we're back to end 2019, pre-covid, except much more indebted. With MV=PY in mind, it's hard to picture sustained inflation.

Thank you very much Carl. Ok, I understand that the banks already own the treasuries and, then, it is just an asset swap. But, what if a bank owns no treasuries, or has already sold them all, how then does the Fed increase Reserves, with no treasuries to swap? Or, can it not do so? Thanks.

^The world has become dependent on a large supply of US government debt liabilities. These are HUGE primary and secondary markets. Someone, somehow needs to hold those securities and is available for open market operations.

Read here for a complementary perspective:

https://www.pragcap.com/who-will-buy-the-bonds/

By and large, the amount of debt and associated money that people 'carry' around is dictated by the Fed-Treasury complex. If banks do not hold government debt, who will? And what will they buy instead? junk bonds? stocks?

I think the Fed is getting to distracted these days and that is why they missed inflation. Asking them to help with climate change is a waste of their time. Now racial and economic injustices lol.

https://summit.news/2022/06/27/new-bill-would-mandate-federal-reserve-to-promote-racial-and-economic-justice/

re: "With MV=PY in mind, it's hard to picture sustained inflation"

The equation of exchange is dependent upon the time period. The distributed lag effect of money flows, the volume and velocity of money, is based on the time period. The time period is a mathematical constant.

Since the FED won't drain the money stock, the only variable to consider is Vt. Using interest rate manipulation as the FED's transmission mechanism, velocity falls when policy rates are hiked to unaffordable terms.

The problem arises because short-term money flows (proxy for real output) is impacted more so, or sooner, than longer-term money flows (proxy for inflation). So, if the FED decreases Vt, then R-gDp falls relative to inflation. Inflationary pressures require a sustained tightening of monetary policy for > 2 years.

Thank you again Carl. I did read the reference to Cullen Roche's article as well. Makes complete sense.

I would still like to know a hypothetical though. Let's say the banks and the secondary non-bank institutions don't, as a whole, have anymore money to buy treasuries, i.e. they don't have anymore excess reserves, nor treasuries to sell to the Fed. Where does the money come from to buy the new issuance of the treasury? Thanks.

@Unknown

What you're asking is not clear.

Go on though as it is a really important topic and even central bankers (Plosser) don't seem to get it right (he just came out saying consumers are flush with cash and ready to weather a downturn etc etc).

BTW money stock measures are coming out later today and it may be time to integrate forward looking indicators into changing previous monetary trends.

Central banks now typically over-reach, focus on lagging indicators and don't seem to grasp that their 'interventions' work with very long lags.

I mean really, in the scenario where banks (or secondary non-banks) do not have any additional balance sheet assets to buy anything (or sell to the FED), how does the FED then increase reserves? Or how can new Treasury issuance be bought? (am I beating a dead horse?)

@Unknown

Quantitative easing and tightening are happening in a world of expanded balance sheets with excess money/reserves and with a lot of Treasury securities being issued.

What is unknown is how difficult it will be to reverse open market operations and to get back to normal levels. In 2019 (before Covid), it became clear (liquidity stress in related markets) that the Fed could no longer reduce reserves in the banking system, even if still wildly ample in nature. This has largely remained unexplained in the mainstream but it appears that tightening in a yield-curve-inversion environment gives rise to unexpected and unintended consequences that can have an impact on government funding, so your 'liquidity' questions are relevant in practice even if felt irrelevant (by some) in theory.

Thank you again Carl. I see, there never is a problem with "buying more" (debt, treasuries, whatever): the larger the balance sheets the more they can expand. There is no banking physical constraint - only the Fed - when it decides to constrain because of inflation.

Thank you for your claritiy on these difficult matters.

Richard

Take a look at FRED St. Louis data on assets held by the FED ("WALCL").

During the period 1.06 - 22.06 the balance sheet has actually increased by ca. 19 bn USD.

Does FED really intend to taper?

"Does FED really intend to taper?"

Their most important function is relative price stability.

Lately Fed's actions and inactions have contributed greatly to the recent inflation episode (painful for majority and for the 'people' they are supposed to "help") by:

1-QE and Fed balance sheet expansion

2-allowing banks to buy government debt (and increase money supply mostly through checkable accounts)

3-and by allowing, in general, an unsustainable rise in government debt (and total debt) vs real underlying economic potential

Taper on 1- started recently.

Taper on 2- has only recently started to happen (with evidence in monthly M2 numbers)

Taper on 3- has not happened yet and will it?

By analogy, in this debt super cycle, this is similar to addiction. 1- means "I can stop anytime I want". 2- "See I've booked my rehab" and 3-?

Of course, in the event of more extend-and-pretend, this will not get any easier.

re: "nor treasuries to sell to the Fed"

That was the case during the GD. There was no "eligible" collateral. Governments weren't eligible until the 1933 banking act. And the presidents ran on balanced budget platforms.

^This needs some clarification. :)

In the initial Federal Reserve Act and from the intent of the 'founders', the discounting of debt instruments in open market operations was supposed to be exclusively directed to self-liquidating and short-term private bills (the real bills doctrine). The founders felt using government securities would endanger independence and prevent effective control of the political drive to spend beyond real means. They also felt that using government securities as collateral would have the potential to move money from productive to non-productive uses. (!)

However, with WW1, the 1920-1 recession, the GD and the post-GD public 'investments' in the recovery, gradually, open market operations started to involve more and more government securities. It was an inevitable development due to many factors, a situation which did not permanently negate the founders' apprehension about lack of effective control. Over time and accelerating, open market operations using government debt have become massive, long-lasting and now (since GFC and accelerating since Covid) involve direct financing of government debt through the capture of commercial banks.

The founders' apprehension about eventual inflation potential proved to be right, even during a secular deflationary cycle.

Of course, the Fed has the capacity to bring the pendulum back but will they?

Thank you Carl for bringing in the history of this - and the clarity, and reasonableness of your thought.

Richard

Thank you Scott! Another wonderful summary. I'm curious how you view the argument made by Luke Gromen, and today by Red Jahncke in the WSJ, that the Fed will need to stop the rate increases because the stress on Treasury refinancing will be too great. In your view, would this lead again to excess M2 growth and a sustained inflation into 2023?

https://www.wsj.com/articles/high-interest-rates-will-crush-the-federal-budget-inflation-debt-spending-costs-recession-economy-11656535631?mod=opinion_lead_pos8

Unknown, re Fed needing to stop rate increases. I think the author of the WSJ article is guilty of not understanding how the bond market works. He assumes, for example, that if "Treasury notes roll over at the same spread [150 bps] over the projected year-end fed funds rate of 3.4%, they will bear interest at 4.9% ..."

Currently, 5-yr Treasuries yield 3.04%, and the bond market is priced to the expectation that 5-yr Treasuries one year from now will yield 3.07%, because presumably by then the Fed will have ceased tightening.

He is assuming, therefore, that the bond market is going to be very wrong and yields are going to be a whole lot higher in the future than anyone is now projecting. If he's right, of course, then there will be reason aplenty to worry. But we can't know at this point.

He also fails to take into account ongoing inflation, which will likely reduce the burden of federal debt by at least 7-10% over the next year or so, and that is a significant miss. Also, ongoing inflation will automatically raise federal revenues.

Complementary comments

The key is to keep the growing nominal debt in line with growing nominal GDP.

Financial repression (rates on debt lower than inflation) is a seductive idea but typically ends in disaster. The post WW2 period is often cited as an example of successful financial repression but this is highly misleading. There certainly was financial repression which helped at the margin but the two major factors at work were: fiscal discipline and, especially, amazingly high real GDP growth. The federal debt to GDP went down significantly essentially as a result of high real growth and this momentum carried forward even during the Reagan years when fiscal deficits were becoming large. High real growth will help with debt, polarization etc etc but 'we' need the ingredients for such high real growth.

Growing debt in a low or declining real growth environment is potentially painful. For example, when one looks at the federal debt and general level of debt to GDP during the Great Depression, it's not the rising debt that made the ratio to spike++, it was the brutal decrease in growth.

Post a Comment