So here is a collection of a dozen or so up-to-date charts that show the status of the market-based indicators that I believe merit ongoing scrutiny. My overall interpretation of these indicators is that the economic and financial fundamentals look sound, and although risk asset prices are high from an historical perspective, they are not high in relation to other variables, and they are undergirded by a healthy degree of skepticism and caution. In short, if the threats of the Kung Flu and Bernie Sanders fade, there is still substantial room on the upside for equities.

Chart #1

Chart #1 compares the level of the real (ex-post) Fed funds rate (blue) with the slope of the Treasury yield curve from 1 to 10 years. Note that every recession on this chart has been preceded by a substantial rise in the real funds rate (and a substantial increase therefore in real borrowing costs) and a flat or negatively-sloped yield curve. Today those conditions are nowhere to be found. Real borrowing costs are historically low, and the yield curve is not inverted. (As other charts below will show, substantial portions of the yield curve are still positively sloped.) This means that the Federal Reserve's monetary policy poses no threat to the economy. It would be fair to say that the Fed's current monetary policy stance is broadly neutral.

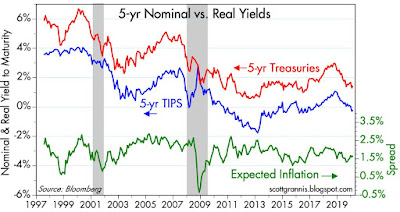

Chart #2

Chart #2 compares the real yield on 5-yr TIPS (blue) with the nominal yield on 5-yr Treasuries (red). The difference between the two (green) is the market's expectation for what the CPI will average over the next 5 years. At 1.6%, the market expects inflation will be below the Fed's upper target (2% on the PCE deflator, which would correspond to abut 2.4% on the CPI). While this might be disconcerting to those who believe that a 2% inflation rate is optimal, I would argue that 2% is unnecessarily high; I would always prefer inflation to be as close to zero and as stable as possible. Regardless, there is no indication in market-based signals that the market is worried about the Fed being too easy, and that is the one thing I would really worry about, since that would pose the specter of a tighter Fed to come and a likely recession to follow.

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares the real yield on 5-yr TIPS (red) to the real (ex-post) yield on the overnight Fed funds rate (blue). The former is essentially the market's expectation for what the latter will average over the next 5 years. As such, today the market is not expecting the Fed to do anything that might jeopardize the economic outlook. Indeed, the market currently expects the Fed to lower rates at least once in the next year or so, and then to keep rates flat. From several perspectives it is clear that the Fed does not pose a risk to markets or the economy. Thank goodness!

Chart #4

2-yr swap spreads are very significant coincident and leading indicators of financial market and economic health. In normal circumstances they would trade in a range of 5-35 basis points. At current levels, swap spreads tell us that liquidity both here and in the Eurozone is abundant—central bank monetary policy is non-threatening, to say the least. This further suggests that the outlook for the global economy is healthy, and systemic risks are low.

Chart #5

Chart #5 shows 5-yr Credit Default Swap spreads for generic investment grade (blue) and high yield corporate bonds (red). This is a highly liquid market, and an excellent proxy for the market's confidence in the outlook for corporate profits. Current levels are relatively low, and this implies that the market is not concerned that profits will disappoint. That, in turn, would imply a favorable economic climate in the years to come.

Chart #6

Chart #6 shows two measures of actual corporate credit spreads. As with Chart #5, it is clear that the market is relatively confident regarding the future health of corporate profits.

Chart #7

In contrast to the preceding charts, which paint a picture of optimism regarding the future, Chart #7 reflects a lot of concern regarding the future. Since inflation is expected to be at least as high as current 10-yr Treasury yields (which are within inches of all-time lows), the market is pricing inflation-adjusted, risk-free returns to be somewhere in the neighborhood of zero. The only way this makes sense is to first recognize that Treasury bonds are the world's top choice for a hedge against future risk. The market is generally optimistic about the future, but at the same time there is intense demand for an asset that can hedge against the possibility of that optimism proving wrong. Sovereign yields throughout the developing world are all trading at very low levels, consistent with a view that says there is a lot of caution priced into the markets. Risk assets are pricey, but not many are willing to bet the ranch that the future is guaranteed to be rosy. What this says is not necessarily crazy: the market is optimistic, but unwilling to throw caution to the wind. That's healthy.

The time to worry, of course, is when everyone expects the future to be rosy and no one is concerned enough to hedge their risks. That was the case, by the way, in late 1999 and early 2000, when PE ratios were on the moon and real yields were trading in a range of 3-5%.

Chart #8

Chart #8 looks at the slope of the Treasury curve from 2 to 10 years. Here we see that the curve has only a modest upward slope, but nevertheless one that is consistent with conditions in the mid- to late-90s, when the economy was growing at a healthy pace. As Chart #1 reminds us, a flat yield curve is not something to worry about unless real yields are also relatively high.

Chart #9

Chart #9 looks out further along the yield curve, from 10 to 30 years. Here we see that the curve has a very normal upward slope. Nothing alarming here at all.

Chart #10

Chart #10 shows the 6-month annualized rate of growth of bank savings deposits, which comprise almost two-thirds of the M2 money supply. Since these deposits pay little or nothing in the way of interest, the growth in these deposits is arguably a good proxy for the world's demand for safe-haven "money." What stands out of late is the sharp increase in the rate of growth of savings deposits over the course of last year, a time when the world became quite worried about the possibility that Trump's tariff wars could lead to a big slump in global economic activity. Lots of demand for money suggests that lots of people were worried the future might turn out to be disappointing; lots of the world's money was seeking the safe harbor of bank savings deposits. This is very similar to what happened to the demand for 10-yr Treasuries in the past year: demand proved so strong that yields fell to extremely low levels.

Chart #11

Chart #11 compares the level of the S&P 500 index to the ratio of the Vix index to the 10-yr Treasury yield. This ratio is a good proxy, I would argue, for the market's level of fear, uncertainty and doubt about the future. Increases in this ratio have usually been accompanied by falling stock prices and vice-versa. Today, concerns are ebbing and stocks are once again rising.

Chart #12

Chart #12 shows the adjusted PE ratio for the S&P 500, according to Bloomberg's calculations (which use only earnings from continuing operations). PE ratios are above average today, but they are still well below the extremes they reached in early 2000. Earnings per share today are 175% above the levels of 2000, but equity prices are up only 125%. This is not necessarily a bubble.

Chart #13

The inverse of PE ratios is the earnings yield on stocks, which in turn is what the dividend yield on stocks would be if companies paid out all their earnings in the form of dividends. PE ratios must be taken into consideration relative to the yields on risk-free Treasuries in order to judge valuations. 10-yr Treasury yields were north of 6% when PE ratios hit 30 in late 1999, whereas today they are 1.6%. Chart #13 looks at the spread (premium) between equity yields and 10-yr Treasury yields. Today that spread is almost 3%, whereas in late 1999 it was -3%. Back then the market was extremely optimistic about stocks and the economy, because equity investors were willing to give up tons of yield for the supposed "privilege" of owning risky assets. Today the market is far from those levels of optimism. Indeed, equity investors demand an unusually large yield premium to hold equities instead of rock-solid-safe Treasuries.

This is not the stuff of which bubbles are made. There is still a lot of caution priced into the market. If the outlook brightens, there is plenty of upside for risk asset prices.

One other market-based indicator that fascinates me currently is the market for predictions about the upcoming elections. As you can see here, the market is saying that as of today, Trump has a 55% probability of winning in November, with Sanders having a 25% chance of becoming our next President. If you don't agree with those probabilities, I suggest you open an account and buy the contract you think is mispriced. Putting your money on the line has a powerful way of focusing your thoughts. I happen to own the Trump-to-win contract, for which I paid 50 cents on the dollar.

7 comments:

An entirely terrific review of market indicators.

It is interesting that after a 10-year recovery from the 2008 Great Recession, inflation is so tame. During this time the US government has run huge deficits and the Federal Reserve engaged in a large quantitative-easing program. Japan does the same thing, Except more so, and they hardly have any inflation at all.

What does this mean? I don't know. In general, inflation and interest rates have been trending down since about 1980. Based upon my close reading of leading economists, every year from 1980 I expected inflation and interest rates to go up. In my guts I still do.

It is not PC to say it, but the prospect of reducing national debt through quantitative easing programs is fascinating. This would require that sacrilegious heretical proposition of a larger central bank balance sheet.

I am running out of years to try to understand the economy. But someday I would like to know what real harm comes from a larger central bank balance sheet.

The inverted yield curve used to be a great indicator reflecting when too much capital had shifted to equities calling a market top. But, this worked when the US was more closed and this reflected a majority of capital. No longer!

Western investors have opened up Developing/Emerging markets by pouring capital into previously illiquid foreign markets. We take this as Western investors seeking higher returns, but the net effect since 2000 has been a capital flow back to Western markets favoring Sovereign Debt and real estate as newly minted and newly liquid Dev/Emg entrepreneurs seek diversification away from weak protections to individual property. It is the reasons Sovereign Debt has reached 5,000yr low rates with some rates in countries being negative unable to absorb the flow. Negative rates work for foreign investors whose currencies are in decline. US investors fail to see this. Low rates and the inverted yield curve are no longer the useful signal provided in the past.

Western investors shifted equity foreign mkts seeking equity returns, but newly liquified business owners sent capital back to Western mkts seeking safety in assets with which they felt comfortable.

You know that old saying "it's different this time"? It's not different this time, it's different EVERY time. Totally excellent review of the markets with a flexible perspective that allows for exogenous events that might arise but haven't-yet.

It's fascinating to try and understand why Sovereign debt is trading at such low yields given that stock returns have been so strong and this goes to why I believe that being pigeon holed into some historic mantra is such a mistake. The classic case is John Hussman and his 20 year performance of losing money. It's HARD to lose $ over 20 years!

If by some negative miracle Bernie Sanders is elected POTUS, look out below!! Of course most investment advisers will tell you "historic" stock returns are just as strong (if not stronger) under democratic POTUS as under republican. And this is true.

But we have never had an absolutely blind lunatic socialist who has ZERO understanding of markets as POTUS either.

And don't tell me it can't happen. How many expected Trump to be elected at this point in the cycle in '16? I do not EXPECT Sanders to be elected but if he becomes the dem candidate I think we can expect fireworks in the markets between now and November.

Considering that the full yield curve now is under CPI/cCPI I would personally rephrase "This is not the stuff of which bubbles are made" to "This is not the stuff of which bubbles pop"

Without going into details some of the yield differential charts that are showing a rise is reminescent of the stock market peaks of yore. I have to look at this negatively not a signn that 'risk' is still in the markets and thus a time to be bullish. The same thing goes for the equity premium chart. If it is now at a bullish level as you postulate why was it negative in 1982 and beyond when the stock market was just starting its secular upward trend. I think you are reading all of these with rose colored glasses.

Scott, for chart # 12 the PE ratio and the long run average. Have you ever adjusted these series for interest rates and if so, how?

Dear Scott, the Kung Flu seems getting spread quite widely despite measures have been taken by different countries. Would this phenomenon suggested some risks to be noted? Bond, gold, commodities are pricing in the risks now? Will the stock market to follow? Kung Flu, may not have high fatality rate, however, it puts social activities or business events into halt...that makes it different from "flu"...

Post a Comment