Yesterday the FOMC decided to keep its target Fed funds rate unchanged at 5.5%. That was no surprise to the market, but the tone of Powell's press conference and meeting minutes convinced the market that rates are likely to be "higher for longer" than previously expected. Market expectations are now geared to expect one more hike before year end, and only a few cuts by the end of next year. To judge by the market's reaction, there's a bit of panic in the air—maybe this time the much-feared recession that was just around the corner most of the year will finally arrive?

It's a shame that economic growth has come to be feared rather than welcomed. We've had 2% growth for over a year now, and inflation has plunged. Growth doesn't cause inflation; too much money relative to the demand for it is what does. The Fed was late to the tightening party, but they have delivered in spades. Today's high interest rates have boosted the demand for money by enough to result in a significant decline in inflation.

Chart #4 shows a measure of housing affordability, which today is as low as it has ever been, thanks to the combination of soaring home prices and soaring mortgage rates. (I would guess that the affordability of homes in the Los Angeles area would register about 60 on this chart.)

Chart #6 compares housing starts to an index of homebuilder sentiment. Both have dropped sharply from the highs of the past few years. Since early last year, housing starts have fallen almost 30%, and homebuilder sentiment has dropped by almost 50%. Over the same period residential construction spending has dropped about 10%—with further drops very likely to come in the months ahead (residential construction spending is highly correlated to housing starts, but with a lag).

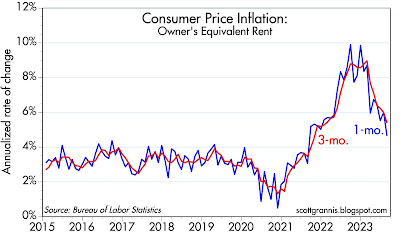

It's terribly unfortunate, but the Fed worries that they haven't done enough, and that they may have underestimated the economy's strength. This tells me that the Fed is overlooking some very important developments: 1) the fact that inflation by current measures has already fallen within range of its long-term target (see Chart #7 in this post), 2) the ongoing slowdown in the growth of private sector jobs, and 3) the emerging weakness in the housing market.

This post focuses on the housing market, which has suffered a triple whammy of soaring home prices, soaring mortgage rates, and soaring spreads over Treasuries that has combined to crush new mortgage applications, weaken housing starts and cool builder sentiment.

Chart #1

|

Chart #1 shows the nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) index of national home prices according to Case-Shiller. (Note: the June figure is actually an average of April, May, and June prices). Home prices are within inches of their all-time highs, and 15% higher, in inflation-adjusted terms, than they were at the peak of the housing market boom in 2006.

Chart #2

revise?????

Chart #2 shows the level of 30-yr fixed rate mortgages (blue), the level of 10-yr Treasury yields (red), plus the spread between the two (green). As is widely known, 10-yr Treasuries set the bar for fixed rate mortgages. In normal times, mortgage rates tend to be about 150-175 basis points higher than Treasury yields. Today, however, they are about twice as high as that (320 bps). Treasury yields have surged from 1.5% in early 2022 to now 4.4%, and mortgage rates have exploded from 3% to now 7.25%. Since the effective rate today on all outstanding mortgages is about 3.7%, anyone refinancing or taking out a new mortgage faces the prospect of a huge increase in mortgage payments on top of housing prices that have climbed to record levels. It's enough to make nearly everyone think twice. And what they're thinking is that borrowing money today is not a pleasant experience. That is how higher interest rates increase the demand for money: it's better these days to be long money than short money—in the sense that being "long" means you own it, while being "short" means you owe it. What a change from a few years ago, when I noted repeatedly that the Fed was encouraging people to "borrow and buy."

Chart #3

Chart #3 shows an index of new mortgage applications, which are down 70% from the highs of the mid-2000s, and down over 50% from the highs of late 2020. Housing market activity has been severely impacted by higher rates, and the Fed's stance today promises no relief for the foreseeable future. This is powerful evidence of an increase in money demand.

Chart #4

Chart #5

As Chart #5 shows, since early last year existing home sales activity has dropped by 36%, to levels not seen since the depths of the housing market slump in 2010. Very few want to sell, and very few are able to buy. This is evidence that the housing market is unstable. Very low turnover means that prices are not a reliable indicator of value.

Chart #6

All of this is reason enough to question the overall strength of the economy. Lurking in the background are $2 trillion annual deficits fueled by excessive and wasteful government spending, the Biden administration's recent throttling of oil exploration and drilling activity, and soaring energy prices. Very expensive energy, just like high taxes, are sure-fire ways of throttling economic growth. Too much government spending is almost guaranteed to sap the economy's strength.

Conclusion: The Fed is highly unlikely to deliver on its "higher for longer" interest rate target for much longer. In coming months events are likely to transpire which will convince both the Fed and the market that inflation is lower and the economy is weaker than commonly thought. And that interest rates need to come down.