On the eve of what is likely to be the end of this cycle of Fed tightening (even if the Fed hikes rates 25 bps tomorrow, they will almost surely convey the impression that no more hikes are envisioned), this blog continues its coverage of the all-important money supply figures. The June M2 number was released today and it was unremarkable. Year over year M2 growth is running at about a -4% rate, while M2 has been relatively flat over the past three months. This is consistent with further declines in inflation over the next 6-9 months.

It continues to amaze me that only a handful of Fed watchers pay any attention to the M2 money supply. The vast majority of inflation-related commentary—including that of the Fed itself—lavishes attention on just about every inflation indicator and variable except the money supply. Milton Friedman must be rolling in his grave. As he famously said, "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." Inflation happens when the supply of money exceeds the demand for it, and the lags between money supply and inflation are "long and variable." So when the US M2 money supply grew at a 20-30% annual rate in 2020 and early 2021, a big increase in inflation was very likely to show up in early 2022. And, not surprisingly, it did.

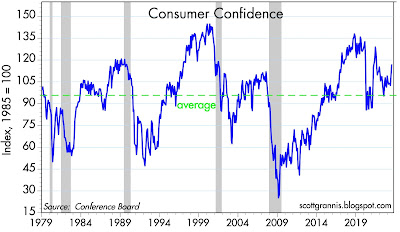

Chart #4 shows the Conference Board's index of consumer confidence. July's figure was reported today, and it showed a welcome increase. This supports my long-held contention that there is no reason to worry about an imminent recession. The economy is likely to continue growing for the foreseeable future, albeit at a relatively unimpressive rate of 2% or maybe a bit less.

We've now seen M2 growth not only collapse, but actually turn negative over the past two years. Again, not surprisingly, inflation began to decelerate dramatically starting about one year ago. More recently, M2 growth has been flat for the past three months, so to the extent that some observers, like Brian Wesbury, worry that collapsing M2 portends an eventual recession, the M2 news has become much less worrisome.

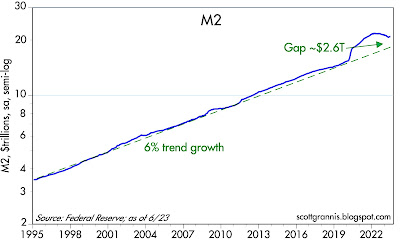

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of M2 relative to its long-term trend growth rate of 6% per year. (Note that the y-axis is plotted on a log scale, so a straight line represents a constant rate of growth.) M2 is still about $2.6 trillion above trend. I've interpreted this to mean that there is still a lot of liquidity in the economy, and this should act as a buffer against adverse developments.

Chart #2

Chart #2 compares the year over year growth of M2 with the rate of consumer price inflation, with the latter shifted to the left by one year to illustrate the fact that there is approximately a one-year lag between changes in M2 growth and changes in inflation. The chart strongly suggests that the CPI is on its way to zero over the next 6-9 months. As such, it's reasonable to conclude that the Fed has acted appropriately, if belatedly, and no further tightening is therefore necessary; lower inflation is "baked in the cake" at this point.

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares the growth rate of M2 with the 12-month running sum of monthly federal budget deficits. This chart strongly suggests that most or all of the deficits from 2020 through early 2021 were monetized. In other words, the massive Covid-era spending blowout was financed with money that was effectively printed. Fortunately, the rising deficits we have seen in the past year have not been monetized, so there is no reason to worry about a resurgence of inflation fueled by excess M2 growth.

Chart #4

Will we have disinflation or actual deflation negating some of the last couple years inflation. And will the recent durable goods inflation trend revert back to deflating long term.

ReplyDeleteGood questions! As always, the answers depend on what the Fed does going forward. If they stay too tight for too long, we'll eventually end up with some deflation. I hope it doesn't come to that. It's bad enough for the economy to have to adjust to a higher price level (as it has been doing), but to then have to adjust to a lower price level would be a little like rubbing salt in a wound. And then there's the issue of our huge national debt. A too-tight Fed and higher interest rates will, before too long, result in enormous debt servicing costs.

ReplyDeleteIf the upper income quintiles hold most of the savings' inventory (M2 2.6T gap), then the on-going draw down should slow.

ReplyDeleteThe "means-of-payment" money supply has contracted for 2 consecutive months. The only thing holding up the economy is the fall in excess savings. The personal savings rate is subpar:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PSAVERT

We have a bifurcated economy:

Per Stockman - BEA's Per Annum Growth of Real Personal Income Less Transfer Payments:

Feb. 1960 to Feb 2000: +3.62 percent;

Feb. 2000 to Feb. 2020: +2.08 percent;

Feb. 2020 to May 2023: +0.61 percent.

Scott - Was the deficit NOT monetized over the past year because of the debt-ceiling debate? and now that the debt ceiling has been raised in June we will NOT see more debt monetization? also - as Wesbury has pointed out, where is the FED getting the funding to pay the interest to the banks on this excess-money-policy which has never been tried before? The FED is loosing money and still paying its employees each month, where will that money come from? The Treasury General Account (TGA) has been increasing again, which isn't a part of the M-2 measurement. I believe?? TGA - went from $45 billion just before the debt-ceiling deal with the June 8 report to $537 billion on July 20 report.

ReplyDeleteRe monetization of the deficit. I've commented before that neither I nor anyone I know has been able to fully account for just how $6 trillion of deficits were monetized. We only know it happened. Outside of the unique nature of the Covid crisis, US deficits have never been monetized: Treasury borrowed money from the private sector in order to fund its deficits. No money was created as a result. The Covid era was the Great Exception to this rule. I'd like to think that future deficits will not be monetized, and so far that has been the case, as Chart #3 shows.

ReplyDeleteFor many years the Fed made enormous profits as a result of paying out the funds rate and collecting the (higher) yields on Treasuries it owned. That situation is now reversed, with the Fed forced to pay 5.4% to holders of excess reserves, while collecting a much lower rate on the Treasuries it owns. Presumably the Fed is taking back the money it paid to Treasury in the past, with the result that the Fed's new operating losses are contributing to Treasury's borrowing needs.

Re today's FOMC decision to raise rates yet again by 25 bps: I have been wrong to predict they would stop raising rates, but I continue to believe that the Fed is done, and no more hikes are needed or justified. The Fed is simply wrong now the way they were wrong a few years ago when they insisted that rising inflation was "transitory." Eventually they have to bow to reality. I predict that will happen sooner than the market expects. The market doesn't expect a cut to come until at least the first quarter of next year. That seems impossible to me given declining inflation prediction.

ReplyDeletePowell, unfortunately, has not burnished his credentials much if any these past few meetings. His answers to questions are all over the board. It's clear he has no clear-cut theory for what causes inflation, and he has no particular insights into how the data are evolving. He will be proved wrong again, to the detriment of the Fed's credibility. Fortunately the market is seeing through he prevarications; the market is relatively confident there will no further hikes. That's why there was no significant negative reaction to today's meeting.

The Fed is done; they just don't realize it yet.

@scott grannis - you wrote: "Presumably the Fed is taking back the money it paid to Treasury in the past, with the result that the Fed's new operating losses are contributing to Treasury's borrowing needs."

ReplyDeleteThe Fed doesn't take back money from the Treasury, rather it stops remitting profits to the Treasury (so yes, the Treasury's borrowing needs increase when the Fed isn't making a profit).

The Fed will carry a strange item on its balance sheet - a "deferred asset" equal to its cumulative operating losses.

c.f. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-if-the-federal-reserve-books-losses-because-of-its-quantitative-easing/

I prefer the extended Friedman quote:

ReplyDelete“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

- Milton Friedman (Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory)

Thank you Scott - I'm consistently impressed by your honesty and of course your practical application of the changing tides. I've learned in managing money to not "fight the FED" nor what the market (billions of people) want & to admit and adjust when we are wrong. I appreciate your wisdom, engagement while retired and experience even when I might disagree. It's the sharpening through exchange of ideas/action we all need. thank you!

ReplyDeleteBrent -thanks for your addition as well.

from that Brookings article.

ReplyDelete"The Fed can’t default because it can always create reserves to pay its bills. Moreover, the banking sector must hold the reserves created by the Fed, so the Fed cannot suffer from a run on its funding. That said, if the Fed had large enough losses for a long enough time, it would have to create such a large amount of interest-bearing liabilities to cover its expenses that it wouldn’t be able to implement monetary policy appropriately. (In terms of the Fed’s accounting, its losses could outstrip all its future profits.) In that extreme case, the Fed would need to get fiscal support from the Treasury. At times, some foreign central banks have had losses in excess of their capital and nonetheless continued to operate effectively (Chaboud and Leahy, 2013).

Happily, the Fed’s future profits are likely to be substantial, since more than $2 trillion of its securities holdings are financed by currency, on which the Fed pays no interest. Given the low level of real interest rates in recent years and the likely growth of currency along with the economy, the present discounted value of future Fed profits is very large – in the trillions of dollars – and so it would take truly colossal and highly improbable losses before the Fed might be unable to implement monetary policy effectively. (Hall and Reis (2015) examine this issue.)"

Today’s GDP stats confirm what I’ve been saying. The economy is doing fine, growing at a moderate rate. More importantly, the GDP deflator (the broadest measure of inflation) rose at only a 2.2% annualized rate in the second quarter, and the deflator for domestic purchases rose at an annualized rate of 1.9%! Inflation by this measure (arguably the best, broadest and most recent) has essentially fallen to the Fed’s target level, if not lower. This is just great news. The Fed refuses to see it, but sooner or later they will have to concede. The Fed is done. No boom, no bust, with relatively low inflation. No wonder the stock market is cheering.

ReplyDelete"Fortunately the market is seeing through he prevarications; the market is relatively confident there will no further hikes."

ReplyDeleteBeg to differ, but yields are up substantially today and if we can agree that longer duration treasury yields are a harbinger of inflation, the bond market says YES. Which as a bond trader for fifteen years now-is surprising. Obviously, bond traders were spooked with a better than expected GDP print but OSTENSIBLY inflation is largely whipped and coming down. Something is amok and I gotta say, I don't like it.

Two consecutive m-o-m increases in M2 albeit small and still declining y-o-y. Nonetheless, do you have thoughts as to how your outlook would change should this continue?

ReplyDeleteNice Q2 GDP report.

ReplyDeleteI agree, the Fed can stand still.

No one likes inflation, but a couple years around 3% is not the end of the world.

Many central banks globally have 2%, 3% and even 4% inflation targets (Reserve Bank of India).

Chronic housing shortages make getting below 3% inflation an expensive proposition, in terms of lost output.

The resilience of the economy is being determined by the changing composition of the money stock.

ReplyDeleteI don't believe the FED will stop raising until something breaks. Our runaway spending created a need to increase rates. And they may not need to be increased from here but holding rates in a tight range for a decade accompanied by decreased Federal outlays will be a good start.

ReplyDeleteInteresting to look at the Treasury issued iBond rate. Similar to TIPS. Currently at 4.3%, for bonds held May to Oct, but backing out the fixed rate of .90%, they are paying 3.4% based on annualized inflation. The next time they set rates is Nov. The Fed is at 5.5%. One branch of government setting rates at much higher than another, both of which are higher than market rates.

ReplyDeleteYou have demand-side inflation and supply-side inflation. Only price increases generated by demand, irrespective of changes in supply, provide evidence of monetary inflation. There must be an increase in aggregate monetary purchasing power, AD, which can come about only as a consequence of an increase in the volume and/or transactions' velocity of money.

ReplyDeleteThe volume of domestic money flows must expand sufficiently to push prices up, irrespective of the volume of financial transactions consummated, the exchange value of the U.S. dollar ("reflected in FX indices and currency pairs"), and the flow of goods and services into the market economy.

See: “The Great Demographic Reversal” by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan.

Steve Englander, head of macro strategy at Standard Chartered is skeptical of the jobs reports number because of the false overlay of the birth death model. His take:

ReplyDeleteEnglander for these purposes is looking at the non seasonally adjusted numbers, which showed 182,000 private-sector jobs created in July. The birth-death model was responsible for 280,000 of them, which means existing companies got rid of 98,000 positions.

Economists don’t understand money and central banking. Contrary to the Keynesian economists who dominate the FED’s research staff, banks aren’t intermediaries.

ReplyDeleteIt’s virtually impossible for the Central Bank or the DFIs to engage in any type of activity involving non-bank customers without an alteration in the money stock. I.e., deposits are the result of lending and not the other way around.

There is a one-for-one correspondence between demand and time deposits (as loans = deposits). As time deposits are depleted, demand deposits grow dollar-for-dollar.

The composition of the money stock is changing. That’s what is propelling the economy, dis-savings, the conversion of time to demand deposits. I.e., the demand for money is falling, velocity rising. The proportion of TDs to DDs has fallen by 18% since C-19. And the turnover ratio for DDs is much higher than TDs.

Lending/investing by the banks is inflationary (increases the volume and turnover of new money). Lending/investing by the nonbanks is noninflationary (results in the turnover of existing money), other things equal.

ReplyDeleteSee ZeroHedge’s double counting:

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/large-bank-loan-volumes-slump-despite-fed-reporting-massive-deposit-inflows

“The divergence between money-market fund assets and bank deposits remains extreme...”

I.e., the transaction's velocity of money has increased. As Dr. Philip George puts it: “Changes in velocity have nothing to do with the speed at which money moves from hand to hand but are entirely the result of movements between demand deposits and other kinds of deposits”.

$32.5 trillion in debt that can never be paid back -- act accordingly...

ReplyDelete