Thanks to today's release of the November 2nd FOMC meeting minutes, we know that the Fed has "pivoted" as expected; they are backing off of their aggressive tightening agenda. Instead of hiking rates another 75 bps at their December 14th meeting, we are likely to see only a 50 bps hike, to 4.5%, and that could well be the last hike of this tightening cycle—which would make it the shortest tightening cycle on record (less than one year). And they might not even raise rates at all in December—that would be my preference.

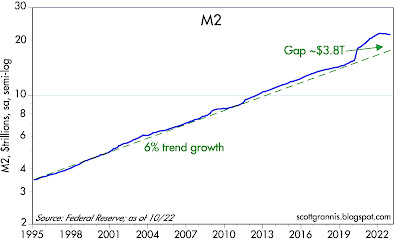

For more than two years I have been one of a handful of economists keeping an eye on the rapid growth of the M2 money supply. Initially I warned that it portended much higher inflation than the market was expecting. But since May of this year I have argued that inflation pressures have peaked: "Many factors have contributed to this: growth in the M2 money supply has been essentially zero since late last year; the stimulus checks have ceased; the dollar has been very strong; commodity prices have been very weak; and soaring interest rates have brought the housing market to its knees. All of these developments mean that the supply of money and the demand to hold it have come back to some semblance of balance." To sum it up, I think the Fed has gotten policy back on track, so there's no need to do more. In fact, the October M2 release showed even more of a slowdown than previously, thus underscoring the need to avoid further tightening.

For a recap of my thinking on all this, here is a short summary of relevant posts:

October '20: On the demand for money and other considerations

March '21: The problem with unwanted money and More signs that inflation is set to increase

July '21: Big changes in inflation and government finances

August '21: Inflation update: this is serious

September '21: Money and inflation update

October '21: Monetary policy is a slow-motion train wreck

November '21: Recession risk is very low, but inflation risk is high

January '22: The bond market is wrong about inflation

Beginning last May I began arguing that we had seen the peak of inflation pressures, thanks to a big decline in the growth of the M2 money supply.

May '22: M2 growth slows: light at the end of the inflation...

August '22: Inflation pressures cool, economic outlook improves

Sep '22: Inflation pressures are in fact cooling ...

I'm still firmly in the inflation-is-falling camp, and it's because of the unprecedented decline in the M2 money supply, coupled with forceful actions on the part of the Fed to bolster money demand with sharply higher interest rates. As a result, I believe we are going to see a gradual decline in inflation over the next year or so.

The following charts round out the story:

Chart #1

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows how the surge in M2 growth was almost entirely driven by massive federal deficit spending from 2020 through late 2021. In effect, the government sent out many trillions in "stimulus" checks to people and most of that money ended up being stashed in bank deposit and savings accounts. The demand for money was intense back then since there was great pandemic-fueled uncertainty and besides, lockdowns left people with little ability to spend money. All that money wasn't a problem until early this year, when the pandemic crisis began to recede. That marked the point when people started to spend the money they had stockpiled, and that spending surge combined with supply-chain bottlenecks to produce a wave of higher prices for nearly everything. In short, an improving outlook and a return of confidence meant that the demand for all that money was evaporating.

Chart #3

(Note: for those who prefer to think in terms of the velocity of money, just invert Chart #3. Velocity is simply the inverse of money demand, and vice versa. Today velocity is definitely picking up. For a longer explanation of this see this post.)

As Milton Friedman taught us, inflation happens when the supply of money exceeds the demand for it. It's critical to understand that rapid growth in M2 from Q2/20 through Q3/21 was not inflationary because the demand for money was very strong during that period. But when the demand for money started to fall early this year, then inflation surged, even though M2 was no longer growing. From this we can infer that the demand for money fell significantly.

Money demand is likely still declining, and money supply is still contracting, but the huge rise in interest rates this year has acted to bolster money demand: earning 4-5% on bank CDs is an incentive to hold on to that money you stashed in the bank—at least some it. The net result of all this is an easing of inflationary pressures. That can be seen already in falling commodity prices and housing prices.

Chart #4

Chart #5

Chart #6

Shall we call this "tightening lite?"