While the world waits anxiously to see if the jobs report this Friday shows that too many people are working—because the Fed (erroneously) believes that might be inflationary and thus a reason to raise interest rates still further—I offer six charts that look at the U.S. economy from a big picture perspective. I don't find anything sinister or strange in these charts. Instead, I see an economy that is growing moderately (perhaps only modestly). I see a healthy labor market, an equity market that is rising at a normal pace, bond yields that have most likely risen by enough to cool inflation, credit spreads that are unremarkable (which is good), and a dollar that has been fortified by Fed tightening.

Chart #1

Chart #1 compares the number of job openings to the number of people looking for jobs. Rarely have openings exceeded the number of job seekers by as much as they have in recent years. What's wrong with that?

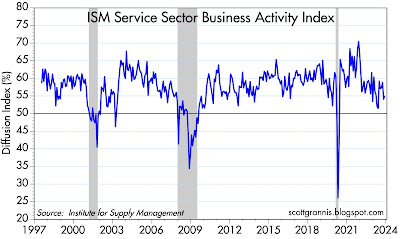

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows an index of service sector business activity. Conditions are still improving (almost 55% of businesses surveyed report improving activity). Things have been better, to be sure, but they would have to deteriorate materially to make me worry about a recession. In any event, this survey suggests that it's reasonable to expect the economy to continue to grow by, say, 2% per year. No boom, no bust.

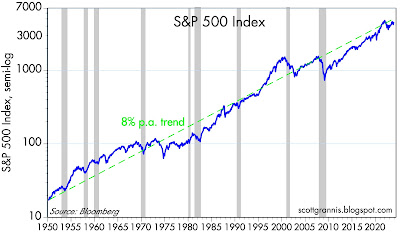

Chart #3

Chart #3 shows the S&P 500 index from 1950 through today. As any student of long-term stock market returns knows, equity prices tend to rise by about 8% per year on average (sometimes more, sometimes less). Add about 1.5% for dividend yields, and you get a long-term total return for equities of about 9.5% per year. Today's market looks pretty normal by those standards.

Chart #4

Chart #5

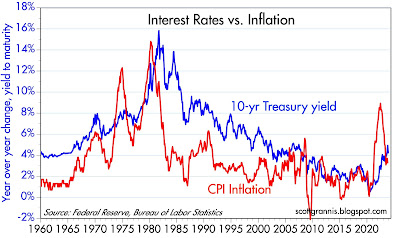

Chart #4 shows the yield on 10-yr Treasuries going all the way back to 1925. It's been a wild ride, to be sure, especially for the past few years, as yields rose by more and faster than at any time in history. Yields hit a low of about 0.5% in the midst of the Covid shutdowns in 2020, and have since risen to a high of 5%; today they closed at just over 4%.

Chart #5 compares these same yields to year over year consumer price inflation from 1960 through today. If—as seems likely—the Fed succeeds in bringing inflation down to 2% or so and holding it there, there's no reason 10-yr yields can't trade in a range of 3.5% - 4%. We're pretty close to that already.

Chart #6

Chart #6 shows two very liquid measures of credit spreads (Credit Default Spreads). Credit spreads are notorious for moving up in advance of recessions and moving down as the economy recovers. That's because credit spreads are driven primarily by the market's outlook for corporate profits, which in turn is a function of the health of the economy. Right now credit spreads are only modestly elevated, which is consistent with a forecast of about 2% real economic growth.

Chart #7

Chart #7 compares the value of the dollar (white line) to the real yield on 5-yr TIPS (orange line). The two have a strong tendency to move together over time. Fed monetary policy is captured in the level of real yields (higher yields mean tighter policy). So a tight Fed means higher real yields, which in turn make the dollar more attractive. The dollar looks somewhat weak of late, and that probably means the market is expecting the Fed to ease policy over the next year or so. And in fact the bond market fully expects the Fed funds rate to be cut 5 times (125 bps) by the end of next year, with the first cut coming in the second quarter of next year. I wouldn't surprised to see the Fed cut rates at the March FOMC meeting, if not sooner. Real yields on 5-yr TIPS will probably be trading around 1% by the end of next year.