The federal government has once again run up against its borrowing limits, and it's going to be Silly Season in Washington DC for the next few weeks. The debt limit will obviously have to be raised, but at what cost? None, according to the Democrats; spending discipline according to the Republicans. Sadly, both parties are complicit in the larger problem: Congress continues to spend money like a drunken sailor, and it has been ever thus, as the charts below show.

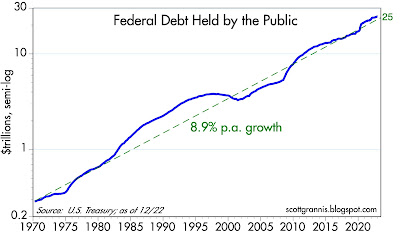

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the staggering growth of federal debt held by the public, which is now $24.6 trillion. It is not $31.5 trillion, as many claim, because that figure includes money that Treasury has borrowed from social security and other government agencies. What the government owes itself is irrelevant; what matters is what our government owes to the public. As the chart shows, debt has been growing at about a 9% annual rate for the past 50+ years. This is not a new problem. (Note: the y-axis is logarithmic, so a straight line equates to a steady rate of growth; a steeper line equates to increases in the rate of growth.) Debt in the past (e.g., mid-1980s, and 2009-2012) has grown at much faster rates than it has recently.

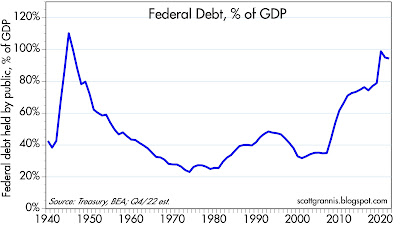

Chart #2

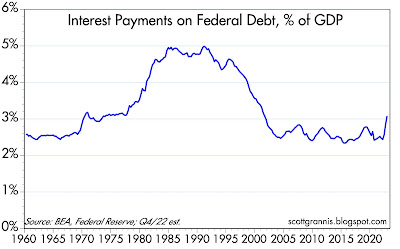

Chart #3

The "burden" of debt is not the nominal amount, nor is it the size of the debt relative to GDP. The true burden is the cost of servicing the debt, which is a direct function of the level of interest rates. As Chart #3 shows, the size of our debt is indeed huge, but interest rates are historically low. Let me point out a curious fact: a rising debt/GDP ratio tends to coincide with falling interest rates, and a falling debt/GDP ratio tends to coincide with rising interest rates. Not what you've been led to believe, I'm sure.

Chart #4 shows the true burden of our debt, which is the cost of servicing the debt as a percent of GDP. That makes sense for the government, just as it makes sense for those who buy a house with a mortgage: what is your monthly mortgage payment as a percent of your income? A bigger economy can easily handle higher debt loads. But rising interest rates added to a very large nominal debt can be explosive. Fortunately, we're not there yet. In fact, the current burden of our federal debt is historically rather low. Sure, it's going to be rising by leaps and bounds in the years to come if interest rates continue to rise and the government continues to borrow. But maybe we'll get lucky (once again) and Congress will rein in spending and inflation will return to the Fed's target without the Fed having to jack rates to the moon. Our debt burden was about 60% larger in the 80s and 90s than it is today, and the sky never fell.

Chart #5 sums it up. Spending in the Covid years exploded, far outstripping the ability of surging tax collections to keep up.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows the true burden of our debt, which is the cost of servicing the debt as a percent of GDP. That makes sense for the government, just as it makes sense for those who buy a house with a mortgage: what is your monthly mortgage payment as a percent of your income? A bigger economy can easily handle higher debt loads. But rising interest rates added to a very large nominal debt can be explosive. Fortunately, we're not there yet. In fact, the current burden of our federal debt is historically rather low. Sure, it's going to be rising by leaps and bounds in the years to come if interest rates continue to rise and the government continues to borrow. But maybe we'll get lucky (once again) and Congress will rein in spending and inflation will return to the Fed's target without the Fed having to jack rates to the moon. Our debt burden was about 60% larger in the 80s and 90s than it is today, and the sky never fell.

The big reason debt rose so much was spending. In the 12 months ended February 2020, federal spending was $4.6 trillion. In the 12 months ended December 2022, federal spending was $6.3 trillion, up 1.7 trillion (36%) from Feb. '20. Taxpayers couldn't keep up the same pace, but the results may surprise you: in the 12 months ended February 2020, federal revenues were $3.6 trillion. In the 12 months ended December 2022, federal revenues surged to $4.9 trillion, up $1.3 trillion (+36%).

Chart #5

Chart #5 sums it up. Spending in the Covid years exploded, far outstripping the ability of surging tax collections to keep up.

Chart #6

Chart #6 puts things into even better perspective. As a percent of GDP, tax revenues today are somewhat higher than their post-war average, but spending remains extremely high relative to its post-war average. Taxpayers are not responsible for our towering debt—Congress is.

No amount of tax increases can fix our problem. We need to rein in spending!

"We need to rein in spending!"

ReplyDeleteUnless we have other choices than the 2 parties of bought-and-paid-for, business-as-usual, career politicians, that's not happening.

Thanks. Somewhat confused - is the debt bad (we need to control spending) or not (it was way worse during the last decade of the cold war and we're just fine)?

ReplyDeleteBtw, seems like if I borrowed from my own 401k to spend on other things (some generating return, others not), I'd still consider that very debt-like. I've got to pay it back in lieu of some other spending down the road. This feels analogous to borrowing from SS.

I am concerned about the debt because I don't understand how the whole bond market works. So, I think up scenarios like this: some big owner of US bonds becomes a forced seller (Japan, China, other?). Interest rates would spike. Then the US would have trouble borrowing more, which starts the dominoes falling.

ReplyDeleteI am sure there are other scenarios that would be of risk to the US govt bond markets.

I have no idea when that might be a "real" risk.

Thanks for the post.

The biggest problem with having so much debt is not the risk of default (a US default is virtually unthinkable), nor the risk of higher interest rates (interest rates are determined by inflation, Fed policy, and the strength of the economy). The problem is that having a mountain of debt like we have means that we have squandered many trillions of dollars of money that could have been used for more productive purposes. A mountain of debt means the economy will be weaker in the years to come. It's a tax on living standards.

ReplyDeleteOne important point that most overlook: repaying the debt is not like flushing money down the toilet. Taxpayers are going to be dinged for the money that goes to those who have bought Treasuries. Money will simply be changing hands: debt owners win, taxpayers lose.

The charges on debt are related to a cumulative figure; and since the multiplier effects of debt expansion on income, the ingredient from which the charges must inevitably be paid, is a non-cumulative figure, it would seem that the time will inevitably arrive when further debt expansion is no longer a practical or possible expedient, either to provide full employment or to keep debt charges with tolerable limits.

ReplyDeleteThen how do you explain the 2019 repo spike?

ReplyDeleteThe short-end segment of the money market would be negative if the FED reduced O/N RRP volumes.

ReplyDeleteScott, I know this question is off today's topic. What's you opinion on the $2 trillion plus that's in the daily ON RRP? What does it mean for monetary policy and financial market liquidity? If it shrinks or expands

ReplyDeletewhat effect does it have on financial conditions?

If you haven't written about it already Scott, I'd love to see your views of a crisis scenario should the U.S. deficit spending not be restrained anytime soon. Be it 5, 10, or 20 years out, if Treasury buyers "slowly then suddenly" demand a significant premium on U.S. yields, then what set of events/trends are most likely to unfold after that point? I assume the starting point is significant stagflation. But how do we get out of that loop if debt burden is significant, and US dollar is possibly crashing?

ReplyDeleteMedicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and "Defense" are all third rails in our politics. They also represent more than 80% of all government spending. So any plan, or even any comment, that doesn't address one or more of these isn't serious.

ReplyDeleteThe American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public's money. -- Alexis de Tocqueville

I would say the Republic has long since fallen. Yes, Congress is to blame for the debt situation. But as PJ O'Rourke wrote in Parliament of Whores, the whores, in the end, are us.

"It is not $31.5 trillion, as many claim, because that figure includes money that Treasury has borrowed from social security and other government agencies. What the government owes itself is irrelevant; what matters is what our government owes to the public. "

ReplyDeleteI have seen this claim made by many, and it makes no sense to me. So Treasury doesn't have to pay principal and interest on treasury debt held by the SS trust fund? if it does, and I take it we have agreement on this point, then how can we ignore these trillions of treasury debt outstanding? isnt the SS trust fund a bona fide holder as much as the Chinese central bank (and you and me)?

MG, re Overnight Reverse Repo Operations: the Fed uses this facility to enable non-federally-chartered banks to use collateral to earn the same rate that the Fed pays on bank reserves. This effectively ensures that the Fed can control short-term interest rates. It broadens the base of those entities that are able to invest in high quality short-term assets. Of course, there is the risk that so many might want to take advantage of this at a time interest rates are soaring that the Fed could go broke, since it would be paying out more than it is earning on it securities holdings.

ReplyDeleteMark, re a crisis scenario: If you assume terrible things are going to happen, then the result is bound to be terrible things happening.

ReplyDeleteGrechster: I share your concern about entitlement spending, which seems immune to budget constraints yet consumes a huge portion of total spending. It can't continue on its current path forever; therefore at some point it no longer will. Social security promises, by the way, are not guaranteed. It might be politically very painful for Congress to change SS payout formulas (e.g., by indexing payments to something less than inflation), but it is by no means impossible and might at some point become inevitable, and it would make a signifiant difference to future deficits.

ReplyDeleteChristian: By way of explanation, let me simplify your question. A large company has two divisions, A and B. Division A's revenues exceed its expenditures, while Division B's expenditures greatly exceed its revenues, with the result that the Division B must borrow significant sums to fund its operations. Management decides to minimize its overall borrowings by using Division A's excess cash to partially fund Division B's expenditures. From a corporate perspective, B owes A money. From the perspective of the outside world, the company is borrowing less than it would need to fund Division B's deficit.

ReplyDeleteIn the case at hand, Social Security is Division A and Treasury is Division B. The name of the company is the US government.

@Scott

ReplyDeleteyour simplification is inapt.

the SS trust fund is not a division of the govt., but is a trust with beneficiaries, and the govt is not a beneficiary of that fund but rather an obligor.

now you make the point that SS distributions are not guaranteed. so does the govt have the power to reduce distributions from the SS fund unilaterally? yes. but the treasuries the SS trust holds are outstanding in any normal use of the word, whether or not they fund distributions for another 10 or 120 years based upon govt meddling with payouts

Why does an ever increasing supply of treasuries not seem to impact rates?

ReplyDeleteShould rates be drifting higher without the FED acting as the largest buyer and source of liquidity for treasuries?

Why is there no inflation premium for 5 - 30s?

Is inflation really going to stay below 3% in the future?

Can you discuss these questions in a future article?

The math isn't going to work in the bond (and mortgage) market for a long time (note- I am not an expert on the bond market, but pretty good at math).

ReplyDeleteThere is a huge number of mortgages at 2-4% that can't be "traded" for a profit for a long time. The long end of the bond market appears to be stubbornly stuck, even when the Fed threatens 6% funds. The business model for mortgages is broken, I guess.

Several things are or will be very broken. It may be able to be fixed, probably with some kind of government intervention (bailout). The problem took about 10-15 years to happen- with a blowoff via Covid responses. It might take that long to work off the problem(s).

Bernanke started it and I think he/they (Fed) knew they were risking a lot. See below.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-REB-12460

We need a new Sec of Treasury, e.g. Sheila Bair.