Bloomberg headline this morning: "US Producer Prices Top Estimates, Supporting Fed Hikes Into 2023"

How do they reach this conclusion? By observing that "the PPI for final demand climbed 0.3% for a third month," when market expectations called for only a 0.2% rise in November. Huh? The monthly change in this index was 0.01% higher than expected, and you think that is a reason for the Fed to raise rates further?

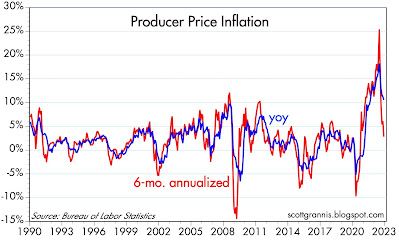

I see it quite differently, as these charts show:

Chart #1

Chart #2

Chart #3

No matter how you look at the data, these charts lead you to an inescapable conclusion: Inflation at the wholesale level peaked in June of this year, and since then it has virtually plunged.

The message this sends to the Fed is clear: there is no reason to raise rates further. Stop the hikes. Whatever you've done so far is definitely working. Don't overdo it!

The message this sends to the Fed is clear: there is no reason to raise rates further. Stop the hikes. Whatever you've done so far is definitely working. Don't overdo it!

Friedman bastardized the concept on his car tag. It’s Irving Fishers’ transaction concept that is right.

ReplyDeleteAggregate demand, AD = M*Vt where N-gDp is both a proxy and subset. Contrary to Blinder, oil’s decline is determined by monetary flows, the volume and velocity of money (not supply shocks):

01/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.998

02/1/2022 ,,,,, 2.011

03/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.633

04/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.382

05/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.320

06/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.231

07/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.195

08/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.280

09/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.143

10/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.094

11/1/2022 ,,,,, 0.851

12/1/2022 ,,,,, 0.549

Salmo, plse share the input variables of this calculations.

ReplyDeleteHi Scott,

ReplyDeleteAll markets have corrections; however, you have recently characterized the drop in the rate of inflation not as a correction, but on our way to a return of low inflation. Same with your comments of commodities - that they are way down - whereas in fact the CRB index is around 300 - up from around 200 in the years before covid. And although certainly off its high of 350, one could certainly make the argument that this is so far only a correction in a very young bull market.

Aside from my analogy of inflation being like other markets, just the fact that M2 grew something like 33% since covid, isn’t there room for a lot more inflation? And isn’t it likely that M2 will continue to grow at greater than 5 or so percent in view of the Treasury’s demands (assuming eventual Fed compliance)?

Can someone answer me this question:

ReplyDeleteIf Bank Reserves cannot be used, or spent, outside the Reserve system, how in the world do banks get the money to buy the trillions of treasuries in the Private markets that they sell to the Fed?

That is, if banks use “inside” (Private) money to buy Treasuries, but only receive in turn “outside” money (Reserves), where do they get the new “inside” money to buy more Treasuries to sell to the Fed??

Thank you.

@Richard H.

ReplyDeleteA useful step is to figure out how deposits have been growing over time.

Note: Salmo Trutta keeps repeating (and he's right about that) that deposits are created by issuing loans but, in a way, it's a chicken or egg type of question, and, to figure out how banks choose what to put on the asset side of their balance sheet, it's helpful to figure out what stands on the liability side, especially the deposits.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DPSACBW027SBOG

great perspective !!

ReplyDeleteHi Carl. Thanks. Isn't the asset side on the banks' ledger, vis a vis deposits, the loans they make? To the extent that there are more deposits than loans, are you suggesting that this amount is substantial enough, over the years, to finance the purchase of Treasuries (that are sold to the Fed)?

ReplyDeleteYes Richard, you are on the right track.

ReplyDeleteFor the longest time and under 'normal' circumstances, loans grew in proportion to the economy and so M2, deposits etc grew in proportion to the underlying economy.

However, especially since GFC and especially++ since Covid, something like 80% of M2 and deposit growth can be explained by Fed-Treasury cooperation with commercial banks and only (since early 2020) about 20% of M2 and deposit growth arose as a result of private loan growth.

This means that, for the last 20 years, across US commercial banks, the loan to deposit ratio has come down ++ (just look at the big 4 since GFC). This means banks (especially large ones) end up with a large amount of deposits which correspond to money on the asset side of their balance sheet, money which can be swapped for securities (banks will tend to keep a minimum amount of money although interest on reserves has reduced the pressure to buy riskier assets).

So, as a result of disproportionate money expansion (QE and MMT-like), banks, in the aggregate, simply end up with more money which they tend to swap for securities.

Please note though that the Fed, for its QE open market operations, do not (mostly) trade directly with banks (banks tend to hold on to their securities including government debt securities) but trade with non-banks: pension funds, insurers etc

Carl,

ReplyDeleteOk makes sense what you’re saying but I thought legally the Fed could only buy securities from the banks, and that all they could give banks in return was reserves. You are saying that the Fed trades directly with non-banks, which means it is buying treasuries with inside, private money - i.e. directly printing money.

Not quite Richard.

ReplyDeleteThe Fed conducts its open market operations in the secondary market. So any market participants could transact with the Fed, including commercial banks. It just happened that most transactions occurred with large non-bank participants.

When the Fed 'buys' the government debt security from a non-bank, it puts the security on its balance sheet as an asset and, simultaneously, prints a virtual dollar as a liability (reserves deposited at the Fed). In this specific transaction, from the bank's perspective (balance sheet), new reserves (asset for the bank) are deposited at the Fed and, simultaneously, a deposit is created (liability for the bank) in the name of the non-bank participant that uses the bank as an intermediate party.

So yes dollars are created or 'printed' in a way (that will show up in deposits, M2 etc) but not really because, all in all, in substance, the only thing that happened in the private market is that a non-bank participant only swapped a government debt security earning a relatively low amount of interest for another government debt security (virtual dollar) that earns no interest.

The idea was to allow banks to carry excess reserves and this was thought to promote lending. This did not really work out. What happened clearly though is that the non-bank participants tended to reinvest the printed money (which became a hot potato earning nothing) by buying other securities from other non-bank participants driving down risk premia and driving speculation.

Thank you Carl. Finally!, I feel like I am getting the picture.

ReplyDeleteSo, to be clear, the non-bank participant (after selling treasuries to the Fed via a member bank) now has private money to do what they want with it. Invest in other securities, etc (or if the non-bank participant is an individual investor perhaps buy a car)?

If so, why is it I read from Scott and others that there is really no new private money being created when the Fed buys treasuries?

The way you have described it is:

A. Private party invests their money to buy treasuries from US Treasury.

B. Private party sells the treasuries to the Fed, via a bank, and gets their money back.

C. End result: private party is unchanged, but US Treasury has money created by the Fed (via one step through a private party).

How can this not be inflationary? True, the money usually stays in the financial sector (inflating the financial sector) as opposed to buying a new car, but it is still adding new printed money to the economy.

Until the Fed takes it away by selling the treasuries …

Which it may never be able to do …

Is this correct?

Thank you!

China just reported deflation on their PPI, and very modest inflation on the CPI. India's inflation just today came back to within their central bank's target range. That about 2.5 billion people, btw.

ReplyDeleteIn the US, house prices are down, used car prices are down, and a lot else is stabilizing.

This is happening despite the horrible Ukraine mess, and post-pandemic jitters.

The Fed should even hold steady, IMHO. The pundits say 0.5% hike on Wednesday.

Hi Richard,

ReplyDeleteIf you look at numbers released by the Fed from 2009 to 2019, you will realize that all excess deposit growth over loan growth can be essentially explained by the growth of the Fed balance sheet (rounds of QE). Was it inflationary (consumer inflation) then? Likely yes, to some degree and at the margin, but not greatly so.

Since 2019 and up to recently, excess deposit growth (huge and unprecedented) can be essentially explained by further QE but ALSO commercial banks' balance sheet expansion to hold US government debt (MMT-style government financing) and the unusual combination has resulted in some inflation (consumer inflation).

QE, on its own, unless unusually large (and facilitating unrestrained government debt issue through low interest rates) and unless combined to MMT-style policies will not be a significant consumer inflation variable.

BTW, Japan, through a similar mechanism, has started to see inflation and if the economy refuses to cooperate, they may be on the slippery slope leading to significant inflation through flight from currency (Yen no longer appreciated as a safe haven).

Then, why would someone further support ("and hold steady") an ample reserves regime; so un-American?

Interest on reserves, the CBDC, and a higher inflation target are all related to the FED's economic failures. The error in economics is the Keynesian macro-economic persuasion that maintains a commercial bank is a financial intermediary. Never are the banks "intermediaries" in the savings-> investment process.

ReplyDeleteFrom the standpoint of the entire system, commercial banks never loan out, and can’t loan out, existing funds in any deposit classification (saved or otherwise), or the owner’s equity, or any liability item. Every time a DFI makes a loan to, or buys securities from, the non-bank public, it creates new money - demand deposits, somewhere in the system. I.e., all new and old deposits are the result of lending and not the other way around.

I.e., banks pay for the deposits that they collectively already own. The source of interest-bearing deposits is non interest-bearing deposits, directly or indirectly via the currency route (never more than a short-term situation), or through the banks’ undivided profits accounts. An increase in time deposits, the bank’s biggest expense item, depletes demand deposits by the same amount. TBTF is the inevitable result.

The drop in inflation should set up a peak in stocks - for a generation. Inflation will once again hit a brick wall in another couple of months.

ReplyDelete"The Treasury's interest costs on U.S. public debt grew 53% or $19 billion during November"

Thanks again Carl. Ok, that makes sense what you, and Salmo, are saying - that QE went into financial assets almost exclusively, at least up until 2020.

ReplyDeleteIn your mind is this still "printing" or "creating" money?

(I realize that Fed bank Reserves can be bought back in - unlike helicopter money which once printed cannot - and this, in turn, would have a knock-on reduction in the money supply. But this seems unlikely to happen, i.e. the printing will likely be permanent. Even with passive QT it seems unlikely that they will shrink their balance sheet much - even before the next crisis hits).

I do have a question for Salmo; you said above that banks cannot loan out even savings accounts. I know that deposits are a function mainly of loans, but I did think that savings accounts can be used for loans. No?

ReplyDelete@Richard

ReplyDeleteTechnically, with QE, money is printed:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lK_rYS8L3kI

But the money printed this way mostly caused asset inflation, not consumer inflation, except if...

In 1945, the US was in a similar situation (the Fed and US banks bought government debt ++). Federal debt to GDP was, like today, at about 100%. Then, the US won the war and household debt to GDP at 10% (vs 75% now) and corporate debt to GDP was at 20% (vs 50% now).

The US will find a way. Don't you think?

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete@Richard

ReplyDeleteThe problem comes from looking at an individual bank vs. the system. It's microeconomics vs. macroeconomics. From a system's perspective, the only valid perspective, a bank never lends deposits. It always creates deposits when it lends/invests.

@Richard (to complement above)

ReplyDeleteLet's say you find 1000$ in your mattress and make a deposit in your bank account. Then the bank has money (1000$) which it can use to 'invest' ie buy a security or whatever to maximize its return on a risk-adjusted basis (versus the interest it will pay for the deposit). The bank does not need that deposit to create a loan. When a loan agreement is made, no net worth is created, only a simultaneous accounting entry is made: a loan as an asset and a new matching deposit (new money) as a liability.

@Salmo Trutta

-A bank always creates a deposit when it invests- is IMO incorrect. It's only an asset swap. If the bank transfers money for the asset to a market entity with no account at the bank, a new deposit (2 matching accounting entries) is created elsewhere but the initial deposit liability that matched the money as an asset is still on the bank's balance sheet after it 'invested'.

Carl,

ReplyDeleteWell, that is a big question - takes in so many things. I do not think America is very much like it was after WW2. I think we have become lazy and fat. We also were on the discipline of a partial gold standard then. Yes, we can keep importing illegal labor to do all our work and grow the economy somewhat - to partially help our debt situation - but we can’t keep doing that forever.

General inventiveness (productivity) will help, but I doubt it will change the deficit/gdp ratio much.

Thank you Salmo. Yes, I understand this. Still I did not want to entirely throw out the common sense prevailing wisdom that banks can loan our their savings accounts. Let's say if a deposit was made from outside the banking system, i.e. sale of a stock, and put into a savings account .. But I realize almost all savings is, as you say, stagnant in the banking system.

ReplyDeleteCarl, Salmo, I also wondered about Salmo's comment that money is created when a bank buys a security. If you are right Carl, that it is not - if it is only a swap - then it begs again my question where banks get the money to keep buying treasuries to sell to the Fed (when all they get in return is Reserves).

ReplyDeleteHi Richard,

ReplyDeleteFirst remember that commercial banks have been net buyers of government debt and agency securities (they haven't bought to sell to the Fed, they have bought to hold onto the securities). From GFC to early 2020 (11 years), they increased their position by 2.9T and since early 2020 (less than 3 years), they increased their position by 1.4T.

Also concerning the following,

"Let's say if a deposit was made from outside the banking system, i.e. sale of a stock, and put into a savings account."

When you sell a security, you end up swapping your security for a deposit from someone else; there is no net deposit creation from saving.

-----

A similar principle applies for the question: where do banks get the cash to buy securities? Banks, in the aggregate, get stuck with money created systemically (either loans originated, QEs or commercial banks' expansion of their holdings of government debt). The money (unless retired ie loans paid back, QE reversed, or comm. banks decreasing their exposure to government debt (ie decreasing direct financing of government debt), with the latter occurring since March 2022) then just stays in the system and participants are stuck with the excess.

When banks swap cash for an existing security with another private market participant, an exact and opposite swap effect occurs in the balance sheet of the another private market participant.

-----

Bottom line, durable wealth is not created through money printing or debt but through positive return on capital invested. Of course, if the latter is done well, capital can be wasted on various projects (redistribution type). Debt and printed money will only carry 'us' so far.

Very succinct and logical Carl. Makes perfect sense. Thank you for taking the time!

ReplyDeleteI hope there are others out there reading the blog who can appreciate it as well.

Good day! Richard

Glad that you found some value in the comments.

ReplyDeletePlease, do not hesitate (anyone) to poke holes in the assumptions/reasoning etc

i continue to wonder how productivity will come to improve over time.

Somehow, this is the way productive growth will occur and the right terms in the MV=PY equation (V and Y) will again contribute to improved standards of living.

Re today’s FOMC action: As the market expected, the Fed raised the funds rate by only 50 bps. However, (and not as I expected) they continued to talk aggressively about further hikes. I continue to believe that’s wrong (they should stop hiking), and the market seems to agree with me. The market is only pricing in at most another 50 bps in hikes next year. I think that pretty soon they will realize they don’t need to hike anymore and will begin to ponder when and by how much to ease.

ReplyDeleteOR They'll overdo it as is their history and send us into a premature recession....

ReplyDeleteMethinks the market reaction today is exactly what Powell is looking for. I significant stock rally fuels more inflation (in his mind).

ReplyDeleteI always say that the fundamental's precede the technical's. As Grannis said, Powell blew it.

ReplyDeleteArmageddon is here now. As Daneir Elloitt Wave claims, we've peaked at wave 2. The 3rd wave down will be disastrous. Note: I only believe in the Elliott Wave in retrospect.

The O/N RRP still has 2 trillion invested, cash for “certificates of confiscation”.

ReplyDeleteI guess Powell disagrees with Scott. He'd rather have a deflationary depression than inflation running hotter than 2%.

ReplyDeleteLarge CDs signal a recession

ReplyDeleteLarge Time Deposits, All Commercial Banks (LTDACBM027NBOG) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

Economists just don’t get it. Banks don’t loan deposits. An increase in bank-held savings destroys the velocity of circulation. So, we get FOMC schizophrenia: Do I stop because inflation is too high? Or do I go because R-gDp is falling?

All monetary savings, bank-held savings, originate within the commercial banking system. Demand deposits are just shifted into time deposits.

Since time deposits (income held beyond the income period in which received), a component of M2, originate within the banking system (and there is a one-to-one relationship between time and demand deposits — an increase in TDs depletes DDs by an equivalent amount), there cannot be an “inflow” of time/savings deposits and the growth of time/savings deposits cannot, per se, increase the size of the banking system.

From a system standpoint, TDs constitute an alteration of bank liabilities, their growth does not per se add to the “footings” of the consolidated balance sheet for the system.

Salmo: if Bank A receives a huge influx of savings deposits from, say, employees of a firm that has paid a bonus using funds it holds in Bank B, Bank A must do something with the money in order to earn the money it will pay in interest to the savers. Bank A can make loans to local residents or it can buy securities, sell them to the Fed, and then hold on to the reserves it receives from the Fed in payment. Bank reserves are equivalent to an investment, and they are equivalent to lending to the Fed.

ReplyDeleteOh dear. Here I was now sure of the logic that Salmo - and Carl - have been explicating, and, now, Scott you have thrown a monkey wrench. Where do I/we turn now?

ReplyDeleteI believe I could preempt what Salmo and Carl would say: that Bank A is just getting the funds that were in Bank B; i.e. there is no change in the overall bank deposits picture.

But I never have really understood why Salmo says all the bank deposit money is stagnant, dead, money (perhaps I am misreading this interpretation). Yes, it seems to be doing a function of investment in US debt/treasuries. Or is it just not as much velocity as if it were in non-bank investments?

That banks act as intermediaries is the biggest mistake in the history of the world. While commercial bank-financed investment elicits forced savings (and subsequent voluntary savings) from the public, investment financed by intermediaries must be preceded by voluntary savings.

ReplyDeleteSavings is not synonymous with the money supply. Don't conflate an individual bank's operations with the operations of the system. The increased lending capacity of the financial intermediaries is comparable to the increased credit creating capacity of the commercial banks in only one instance; namely, the situation involving a single bank which has received a primary deposit.

But this comparison is superficial since any expansion of credit by a commercial bank enlarges the money supply, whereas any extension of credit by an intermediary simply transfers the ownership of existing money.

You have to retain cognitive dissonance capacity, like Walter Isaacson described Albert Einstein’s ability: to hold two thoughts in your mind simultaneously – “to be puzzled when they conflicted, and to marvel when he could smell an underlying unity”.

It’s stock vs. flow. I.e., transaction deposits which have been shifted into savings deposits have a zero payment’s velocity.

ReplyDeleteThe gist of it is that because banks don't loan out savings, all bank-held savings are frozen, lost to both consumption and investment. Banks don't lend/invest deposits. Deposits saved beyond the income period in which received, are the result of lending/investing.

The lending capacity of the payment’s system is determined by monetary policy. It is in no way dependent on the savings practices of the public. People could cease to hold any savings in the commercial banks and the lending capacity of the payment' System would be unimpaired.

The lending capacity of the payment’s system is a function of the velocity of its deposits, it is not a function of its volume of deposits.

All monetary savings originate within the payment’s system. The source of interest-bearing deposits is non-interest-bearing deposits, directly or indirectly via the currency route (never more than a short-term seasonal situation since 1930), or through the bank’s undivided profits accounts.

Since time deposits originate within the banking system (and there is a one-to-one relationship between time and demand deposits -- an increase in TDs depletes DDs by an equivalent amount), there cannot be an “inflow” of time/savings deposits and the growth of time/savings deposits cannot, per se, increase the size of the banking system.

From a system standpoint, TDs constitute an alteration of bank liabilities, their growth does not per se add to the “footings” of the consolidated balance sheet for the system.

Dr. Philip George's "The Riddle of Money Finally Solved" corroborates Dr. Leland James Pritchard's theory (Ph.D. Economics, Chicago 1933, M.S. Statistics Syracuse)

ReplyDeletehttp://www.philipji.com/riddle-of-money/

"For nearly a century the progress of macroeconomics has been stalled by a single error, an error so silly that generations to come will scarcely believe that it could have persisted for as long as it has done. It is an error that has been committed by John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, John Hicks and James Tobin, Franco Modigliani and Ludwig von Mises, Murray Rothbard and Paul Krugman, and continues to be taught to every economics undergraduate today."

Like Leonardo Da Vinci said of observational evidence, of mechanical laws, of applied science:

ReplyDelete“Before you make a general rule of this case, test it two or three times and observe whether the tests produce the same effects”. This repeatability, notice of certain regularities, works spectacularly well to predict the future. Nothing has changed in > 100 years.

Both the 1966 Interest Rate Adjustment Act, and the reduction in FDIC deposit insurance in Dec. 2012 are prima facie evidence.

Japan is a good example. Japan’s “lost decade” is due to the impoundment and ensconcing of monetary savings in their banks. The BOJ has unlimited transaction deposit insurance, the Japanese save more, and keep more of their savings in their banks.

ReplyDelete“Japanese households have 52% of their money in currency & deposits, vs 35% for people in the Eurozone and 14% for the US.” The BOJ also has unlimited transaction deposit insurance.

Secular stagnation is directly due to the deceleration in velocity (as predicted in 1961 by Dr. Leland James Pritchard, Ph.D., Economics, Chicago 1933, M.S. Statistics, Syracuse).

Professor emeritus Pritchard never minced his words, and in May 1980 pontificated that:

“The Depository Institutions Monetary Control Act will have a pronounced effect in reducing money velocity”.

Percentage of time (savings-investment type deposits) to transaction type deposits:

ReplyDelete1939 ,,,,, 0.42

1949 ,,,,, 0.43

1959 ,,,,, 1.30

1969 ,,,,, 2.31

1979 ,,,,, 3.83

1989 ,,,,, 3.84

1999 ,,,,, 5.21

2009 ,,,,, 8.92

2018 ,,,,, 4.87 (declining mid-2016 with the increase in Vt)

Historical FDIC’s insurance coverage deposit account limits (commercial banks):

• 1934 – $2,500

• 1935 – $5,000

• 1950 – $10,000

• 1966 – $15,000

• 1969 – $20,000

• 1974 – $40,000

• 1980 – $100,000

• 2008 – $unlimited

• 2013 – $250,000 (caused taper tantrum)

It’s stock vs. flow.

Frozen savings ,,,,, Reg Q ceiling %

11/01/1933 ,,,,, 0.0300

02/01/1935 ,,,,, 0.0250

01/01/1957 ,,,,, 0.0300

01/01/1962 ,,,,, 0.0350

07/17/1963 ,,,,, 0.0400

11/24/1964 ,,,,, 0.0450

12/06/1965 ,,,,, 0.0550

07/20/1966 ,,,,, 0.0500

04/19/1968 ,,,,, 0.0625

07/21/1970 ,,,,, 0.0750

It is axiomatic. All DFI held savings are un-used and un-spent, lost to both consumption and investment, indeed to any type of payment or expenditure.

It is Scott Grannis, chart #6 “Money Demand”.

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting that the Federal Reserve is supposed to promote "stable prices and maximum employment" (along with moderate long term rates...), BUT they are almost certainly targeting (although I bet it is not documented anywhere in their records), higher unemployment. This is directly against their legal mandate(s).

ReplyDeleteThe economy would benefit from some inflation in the right spots: wage inflation for lower wage workers, inflation in goods that are usually imported (e.g. via on-shoring).

Wkevinw: The Fed appears to want the unemployment rate to rise because the Phillips Curve still lives in their minds, although it has been regularly debunked. The Phillips Curve says that unemployment must rise in order for inflation to fall. It’s sad to think that our central bank still believes in baseless theories. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon, not the result of low unemployment!

ReplyDeleteGovernment Economic Data: Amazingly Poor Quality (?)

ReplyDeleteEmployment data correction from the Philadelphia Fed:

"10,500 net new jobs were

added during the period rather than the

1,121,500 jobs estimated"

https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/frbp/assets/surveys-and-data/benchmark-revisions/early-benchmark-2022-q2-report.pdf

When the corrections are about the same size as the absolute measurement, you have poor quality data. It's just math/statistics.

Making decisions that impact so many people's lives with this poor quality data should be done with extreme care. If the employment data are this poor (or slow to be corrected), it's going to difficult for the Fed to EVER make policy without big errors.

Wesbury said today that he thinks M2 is being manipulated by the Fed's decision to grow the Treasury General Account from $100B to $600B over the last year. This produces a 4% increase in M2, rather than the 1% reported. Is this a fair concern? He also says it would help explain how total bank credit is still up 7+% in the same timeframe.

ReplyDeleteRe: Brian Wesbury's comments on M2. Brian and I have been friends for many years and we almost always agree on economic and financial issues. However, I find that we don't agree on the impact of a decline in M2 over the past year. He worries that a reduction in M2 increases the chances of a recession, whereas I think it mostly increases the chances that inflation declines. I don't think it puts the economy at risk because even after this past year's reduction, M2 is still way above its long-term trend growth of about 6% per year. In short, there is still an unusually large amount of readily spendable cash in the US banking system.

ReplyDeleteIn any event, I would point out that to the extent money has shifted out of M2 (most of the shift coming out of bank savings accounts) and gone into the Treasury General Account, that money is not money that consumers control, and as such, is not money that could be spent by consumers desiring to reduce their money balances. That in turn implies that the money has acquired less inflationary potential.

Ok Salmo, I am still confused. I read - three times - Dr. P. George's article and it seemed to make sense (though it is always disconcerting, to say the least, when someone has discovered an error that thousands of very bright people have missed for a century. I will grant it is possible however, as it is not a simple error).

ReplyDeleteAssuming what he is saying is true, I still cannot get from that to your position that "All DFI held savings are un-used and un-spent, lost to both consumption and investment, indeed to any type of payment or expenditure".

I do not understand why DFI held savings are not investment. If they are not, how do banks pay us any interest on them - if they are not invested in some way?

I thought the DFIs invest our savings into Government debt?

Thanks.

wkevinw, Re revisions to payroll growth: on the surface, the numbers you site appear to differ by a gargantuan amount and would surely be cause for great concern. However, It is not uncommon for payroll numbers to be adjusted by a significant amount after the fact (the BLS usually revises its benchmark estimates once a year around March/April if memory serves). A 1 million downward adjustment to the current total jobs number (153.6 million) would reduce the year over year growth rate of jobs by about 0.65%, and it would suggest the economy was either somewhat weaker than thought and/or worker productivity was stronger than thought.

ReplyDelete@Richard: It's stock vs. flow. Banks are not intermediaries. From the standpoint of the system, not an individual bank, commercial banks never loan out, and can’t loan out, existing funds in any deposit classification (saved or otherwise), or the owner’s equity, or any liability item.

ReplyDeleteEvery time a DFI makes a loan to, or buys securities from, the non-bank public, it creates new money - demand deposits, somewhere in the system.

Take the “Marshmallow Test”: (1) banks create new money (macro-economics), and incongruously (2) banks loan out the savings that are placed with them (micro-economics).

As Luca Pacioli, a Renaissance man, "The Father of Accounting and Bookkeeping” famously quipped: “debits on the left and credits on the right, don’t go to sleep with an imbalance”

You have to retain cognitive dissonance capacity, like Walter Isaacson described Albert Einstein’s ability: to hold two thoughts in your mind simultaneously – “to be puzzled when they conflicted, and to marvel when he could smell an underlying unity”.

It’s also like Athenian philosopher Plato -- whose "first fruits of his youth infused with hard work and love of study" said: "We seem to find that the ideal of knowledge is irreconcilable with experience”.

In almost every instance in which John Maynard Keynes wrote the term bank in his bible: “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”, it is necessary to substitute the term nonbank in order to make Keynes’ statement correct.

It’s a fundamental macro-economic accounting error based on double-entry bookkeeping as originally conceived by Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli in 1494.

ReplyDeleteProfessional economists have no excuse for misinterpreting the savings-> investment process. They are paid to understand and interpret what is happening in the whole economy at any one time.

For the commercial banking system, this requires constructing a balance sheet for the System, an income and expense statement for the System, and a simultaneous analysis of the flow of funds in the entire economy (see: Financial Accounts of the United States - Z.1.)

Example: The expansion of bank credit and new money, transaction deposits, by the CBs can be demonstrated by examining the differences in the consolidated condition statements for the banks and the monetary system at two points in time.

Increases in DFI loans and investments [earning assets/bank credit], are approximately the same as increases in transaction accounts, TRs, and time deposits, TDs, [savings-investment deposits/bank liabilities/bank credit proxy] excluding IBDDs.

That the net absolute increase in these two figures is so nearly identical is no happenstance, for TRs largely come into being through the credit creating process, and TDs owe their origin almost exclusively to TRs - either directly through transfer from TRs or indirectly via the currency route or through the DFI's undivided profits accounts.

There are many factors, which can, and do, alter the volume of bank deposits, including: (1) changes in currency held by the non-bank public, (2) in bank capital accounts, (3) in reverse repurchase agreements, (4) in the volume of Treasury currency issued and outstanding, and (5) in Reserve Bank credit. Although these principle items are the largest in aggregate, they nevertheless have been peripheral in altering the aggregate total of bank deposits.

For the Monetary System:

Thus the vast expansion of deposits occurred despite:

(1) an increase in the non-bank public’s holdings of currency $801.2b

(2) an increase in other liabilities and bank capital $39b

(3) an increase in matched-sale purchase agreements $32.2b

(4) an increase in required-clearing balances $6.7b

(5) the diminution of our monetary gold and silver stocks; etc.(-)$6.6

(6) an increase in the Treasury’s general fund account $4.9b

Factors offset by:

(1) the expansion of Reserve Bank credit $847.5b

(2) the issuance of Treasury currency; $35.9b

These “outside” factors made a negligible contribution in bank deposit growth the last 67 years of $4.4b (deposits declined by $877.4b and were offset by the expansion of $883.4b).

For the incredulous reader I make this assignment: Please explain how the volume of TRs and TDs could grow since 1939 from $48 billion, to $ 8,490 (NSA) billion, even while the banks were paying out to the non-bank public a net amount of (-)$801.2 billion (NSA) in currency.

Federal Reserve Bank credit since 1939 (2.6b), has expanded by $ 847.5 billion (NSA), (-$801.2 of which was required to offset the currency drain from the commercial banks. The difference in the above figures outlined above was sufficient to supply the member banks with $46b of legal reserves.

And it is on the basis of these legal reserves that the banking system has been able to expand its outstanding credit (loans and investments) by over (+) $8,462 trillion (SA) since 1939. (40.7)

From a System’s standpoint, time deposits represent savings that have a velocity of zero. As long as savings are impounded within the payment’s system, they are lost to investment or to any type of expenditure. The savings held in the commercial banks, in whatever deposit classification, can only be spent by their owners; they are not, and cannot, be spent by the banks

Of interest: "Spike In Fed Discount Window Usage Hints At Looming Bank Crisis"

ReplyDeleteread://https_www.zerohedge.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.zerohedge.com%2Fmarkets%2Fspike-fed-discount-window-usage-hints-looming-bank-crisis

The FED Guy:

https://fedguy.com/trapped-liquidity/

I think Scott Grannis is right about M2. And Eric Basmajian agrees with me that the 1st qtr. of 2023 looks negative. But as Grannis says, there's too much money sloshing around. It takes a negative rate-of-change in money flows for a couple of quarters to start a recession. That doesn't look probable. Looks more like a rolling recession.

. Take R. Alton Gilbert (who wrote – “Requiem for Regulation Q: What It Did and Why It Passed Away”), in his letter back to me on December 11, 1978:

ReplyDelete“Such savings are invested in many ways, including deposits at commercial banks.”

Or take Dr. Daniel L. Thornton:

Re my comment: “Savings are not a source of "financing" for the commercial bankers”

Dr. Dan Thornton’s response:

Thu 3/9, 2:47 PMYou

See the graph below.

http://bit.ly/2n03HJ8

Not only are the Fed's econometric models wrong, but their macroeconomic concepts reflect this. Economists have learned their catechisms, that there is no difference between money and liquid assets (the Gurley-Shaw thesis).

The fact is that the commercial banks are never financial intermediaries (conduits between savers and borrowers).

Fractional reserve (or prudential reserve), banking is a function of the velocity of centralized bank deposits (based on interbank payments, clearings, & settlements). Money creation is not a function of the volume of deposits.

Any institution whose liabilities can be transferred on demand, without notice, and without income penalty, via negotiable credit instruments (or data pathways), and whose deposits are regarded by the public as money, can create new money, provided that the institution is not encountering a negative cash flow, aka, the "Goldsmiths".

As a system, the banks pay for the deposits that they already possess, already own. The drive by the commercial bankers, as perpetrated by the ABA, to expand their savings accounts has a totally irrational motivation, since it has meant, from a system’s perspective, competing for the opportunity to pay higher and higher interest rates on pre-existing deposits in the payment’s system. But it does profit a particular bank, to pioneer the introduction of a new financial instrument, such as the negotiable CD - until their competitors catch up; and then all are losers.

ReplyDeleteThe question is not whether net earnings on assets are greater than the cost of the CDs to the bank; the question is the effect on the total profitability of the payment’s system. This is not a zero-sum game. One bank’s gains is less than the losses sustained by other banks. The whole (the forest), is not the sum of its parts (the trees), in the money creating process.

See the Fed’s propaganda in their own "Bible": by R. Alton Gilbert (retired senior economist and V.P. at FRB-STL) – who wrote: “Requiem for Regulation Q: what it did and why it passed away”, 2/1986 Review.

Dr. Gilbert asked the wrong question. His implicit and false premise was that savings are a source of loan-funds to the banking system. Dead wrong. All savings originate within, not outside, of the payment’s system. The source of time deposits (savings-investment type accounts), is other bank deposits, directly or indirectly via the currency route or through the DFI’s undivided profits accounts. And savings flowing through the nonbanks never leaves the payment’s system.

Gilbert assumed that any potential primary deposit (funds acquired from other CBs within the system, or derivative deposits), were newfound funds to the banking system as a whole.

Thereby in his analysis, Gilbert also assumes that every dollar placed with a non-bank deprives some commercial bank of a corresponding volume of loanable funds.

Gilbert asked: Was the net interest income on loans/investments derived from "attracting" these savings deposits (viz., outbidding other CBs), greater than the interest attributable to the direct and indirect operating expenses of retail and this wholesale "funding"?

Thus, the banksters victory (success at attracting funds from other banks) is Pyrrhic. The DFIs would be more profitable if they were driven out of the savings business altogether.

The dunderheads are running the economic engine in reverse. It is hard for the average person to believe that banks do not loan out savings or existing deposits – demand or time. But the DFIs always create money by making loans to, or buying securities from, the non-bank public.

ReplyDeleteThis results in a double-bind for the Fed (FOMC schizophrenia: Do I stop because inflation is increasing? Or do I go because R-gDp is falling?). If it pursues a rather restrictive monetary policy, e.g., QT, interest rates tend to rise:

This places a damper on the creation of new money but, paradoxically drives existing money (savings) out of circulation into frozen deposits (un-used and un-spent). In a twinkling, the economy begins to suffer.

Further to my comment above on payroll growth: Brian Wesbury just published a nice explanation for why this is not something to be terribly worried about. He and I are in agreement on this: https://www.ftportfolios.com/retail/blogs/Economics/index.aspx

ReplyDeleteSalmo,

ReplyDeleteI don’t want to ask you for a history lesson - although I would love it - but can I at least ask when banking changed from loaning out deposits to creating deposits with loans? And what precipitated it? (I do assume there was a time before digital banking - when there was only coin and currency - that banks did not create money)

Thank you.