Chart #1

Chart #2

Chart #1 shows the dramatic—and ongoing—decline in initial unemployment claims. Ten years ago the vast majority of economists would have said that claims could never decline much below 300K per week, since that was most likely the minimum amount of normal turnover in the labor force. Yet here we are today with weekly claims approaching 200K per week. And as Chart #2 (the ratio of weekly claims to total payrolls) shows, claims have NEVER been so low in recorded history, relative to the size of the workforce. The risk of a typical worker finding him or herself laid off has never been so low. Today, employers are more likely to complain that it is harder to find skilled workers than to complain about the workers they have.

It's a brave new world for workers. But it makes central bankers nervous, since they worry that a tight labor market could result in higher wages that in turn could fuel rising inflation. This worry has its origins in the Phillips Curve theory of inflation, but that theory has never found substantiation in the data—it's the economic equivalent of an old wives' tale. Today's Fed governors are aware of this, so they are not necessarily sitting on pins and needles, but it is a source of policy uncertainty nonetheless.

Chart #3

Chart #3 shows what is arguably not only the most astounding economic or financial thing that happened in the past decade but also the most unbelievable. If you had asked any economist 10 years ago what were the chances of the Fed creating over $2.5 trillion of excess reserves in the space of a few years he or she would have stated flatly: ZERO. It couldn't possibly happen, because if it did it would herald the collapse of the dollar and an inevitable hyperinflation. The consequences of such an event were so terrible that the event itself was considered to be impossible. Yet here we are today with inflation running around 2% (as it has for more than a decade) and the dollar trading pretty close to its long-term, inflation-adjusted average vis a vis other currencies.

Prior to late 2008, when the Fed launched its Quantitative Easing program, excess reserves were measured in billions of dollars, not trillions. The Fed managed monetary policy by adding or subtracting reserves (which prior to late 2008 paid no interest) from the banking system: by creating a scarcity of reserves, banks would be forced to pay more to borrow them, and that would result in higher short-term interest rates. Today, with a previously-unimaginable abundance of reserves, the Fed has resorted to pegging the interest rate it pays banks that hold reserves, and that seems to be working. Regardless, we've been sailing in uncharted monetary waters for most of the past 10 years, and economists are still debating how everything is going to work out in the years to come.

To this day there are still legions of observers who argue that what the Fed did starting in late 2008 was simply a massive amount of money-printing, a desperate monetary stimulus that was necessary to avoid a depression, and the economy has been running on fumes ever since.

Others, myself included, believe that what the Fed did was not monetary stimulus at all. It was simply a rational response to an unprecedented increase in the public's demand for money and money equivalents, which in turn was the result of the near-collapse of the global financial system and the worst global recession in modern memory. The world was running very scared, so the demand for safe monetary assets was nearly insatiable. Unfortunately, there were not enough T-bills (the classic monetary safe haven) to go around. By deciding to pay interest on bank reserves, the Fed effectively made bank reserves equivalent to T-bills, and that was exactly what the world wanted: trillions more of safe, default-free, interest-bearing assets, and the Fed had the ability to create bank reserves with abandon if need be. And so it was that the Fed bought trillions of notes and bonds, and in the process created trillions of T-bill equivalents. I explained this in greater detail in a post five years ago ("The Fed is not printing money"). It did the trick, and now the Fed is beginning to slowly unwind QE, as it should, given how much confidence has returned in the last year or so.

Chart #4

Chart #4 shows that the inflation-adjusted Fed funds rate has been negative for almost exactly the past 10 years. Never before in modern times has this occurred. Those same legions of observers that think QE was monetary stimulus in disguise argue that real interest rates have been artificially depressed by the Fed's actions. I and others, in contrast, argue that real short-term interest rates have been extraordinarily low because of extraordinarily strong demand for safe, short-term assets. If the price of a bond is bid up high enough, its yield will turn negative; it's a simple matter of bond market math. T-bills, and bank savings deposits, have been in such high demand that investors have been willing to accept zero or negative real yields. The Fed has not been artificially lowering rates, the market has driven rates to very low levels because of very strong demand for safety and very high levels of risk aversion.

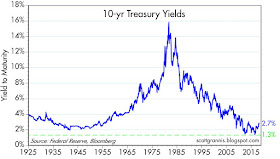

Chart #5

Prior to the Great Recession, most economists would have said that the 2% yields on 10-yr Treasuries we saw in the post-Depression years would never recur, because those yields were the by-product of very weak growth and very low inflation. Yet those same 10-yr yields fell to an all-time low of 1.3% in July 2012, during a period in which the US economy grew at a 2.4% annualized rate and inflation was on the order of 2%. I believe the only way to explain these extremely low yields is to understand that they were driven to low levels by intensely strong demand for default-free assets. After all, the Fed doesn't control 10-yr yields; the market does. Today, inflation is about the same as it was in 2012, but the economy is a bit stronger and confidence is much stronger. Demand for safe assets has declined, as a result, and 10-yr yields have doubled. It all makes sense.

Chart #6

Chart #7

Chart #7 shows how productivity (output per hour of those working) has been extraordinarily low for the past 10 years; this is the main explanation for why growth has failed to snap back to its long-term trend. Prior to the Great Recession, productivity averaged about 2% per year. But productivity has been much less than 2% over the past 10 years. As I've noted, the lack of productivity can easily be traced to weak business investment, which in turn is a natural response to increased tax and regulatory burdens.

Although extraordinary and wholly-unexpected things have happened over the past 10 years, there is still a logical way to understand what has happened and why. And it follows, therefore, that it is reasonable to assume that things could get a lot better in the future if the Fed continues to slowly unwind QE and the federal government continues to reduce our onerous regulatory and tax burdens.

As it has since 2009, I believe it pays to remain optimistic.

Interesting post.

ReplyDeleteregarding charts #6,7. It's kinda hard to swallow that investment over the past 10 years has been stagnant. The iphone came in 2007 therabouts and a LOT has happened since then, especially on the IT front. Seems like we've invented a new way of doing business. Something is getting lost in those figures and therefore the "cure" might not be right either if you are misdiagnosing the problem. The productivity fall is also a puzzle. How much does the data take into consideration investment overseas ? Lots of production capacity has probably been added there to serve a growing and wealthier global population.

Isn't productivity the flip side of employment? When unemployment is high, productivity is high?

ReplyDeleteIt may also be important to consider changes in the nature of employment. For example, I work 4 part-time jobs and am far from alone in that regard. Most of my working life, I only had one.

There may be measurement issues with regard to productivity.

ReplyDeleteProductivity and employment are two different animals, although sometimes they are correlated. Imagine having to hire a dozen workers to handle medicare-related red tape. You get more employment, but those extra bodies are subtracting from productivity, not adding (i.e., they produce nothing of value).

ReplyDeleteMany have speculated over the years that the productivity figures are missing some important ingredient that is not being measured. While I suspect there is some truth to that, I don't find evidence to support the claim that GDP and total incomes are being grossly understated. The "gap" is too big and too persistent to be chalked up to mismeasurement.

I think the evidence points to far greater red tape, as measured by administrative costs, associated with private health insurance as compared to Medicare.

ReplyDeleteOn another note, do you suppose the President might have figured out how to manipulate markets with his Twitter account?

What I hope our President learns is that tariffs manipulate markets in a negative way.

ReplyDeleteyou reason, as always, post ergo propter hoc. you have no evidence of this "insatiable" demand, other than the issuance of the reserves, which is circular reasoning too. and the demand for equity assets? is this proof the other way?

ReplyDeletePrice is evidence, although perhaps not dispositive.

ReplyDeleteRe the "insatiable demand" for safe assets. I think there is plenty of evidence that demand for safe assets (e.g., money, savings deposits, T-bills) was extraordinary, viz: the significant growth of bank savings deposits, despite the fact that they offered little or nothing in the way of interest, the extremely low interest rates on short-term deposits in general, the fact that the Fed felt forced to sell its entire holdings of T-bills in early 2008, and the most important, of course, being the fact that despite the massive expansion of money and bank reserves, there was no increase in inflation and no pronounced weakness in the dollar. If the supply of something expands dramatically but its price does not fall, then its quite apparent that the demand for that thing must have been very strong.

ReplyDeleteAs for equity assets: equities traded at fire-sale prices (e.g., very low PE ratios) for years following the great recession, which suggests to me that demand for equities was not strong. I have plenty of posts which document that this recovery, until a year or so ago, was characterized by lots of risk-aversion, and I stand by that analysis.

Marcus, another way to look at it is that we had a massive increase in the money stock and an implosion in velocity. Those two effects roughly balanced out to produce small GDP growth as well as a small growth in the price level. (The huge demand for safe assets is the exact reason velocity declined so spectacularly despite all the lack of incentives that Scott references.).

ReplyDeleteScott - money supply is finally growing slower than real gdp which is a new phenomena - money velocity is still in a downtrend - the market is finally selling off - the market is usually a good leading indicator but obviously makes lots of mistakes - perhaps we have reached the point of the cycle where the real economy might finally begin to outperform the market as opposite to the opposite the past ten years - im just concerned we are pulling forward demand now with fiscal stimulus and the market multiple is going to go down because the likelihood of a recession in the next two years is going up massively since we have to lap a lot of one time benefits - I want to stay optimistic and I am about the consumer / economy - just finding it harder to be super bullish about the market here - we are only 16x forward pe now which is quite fair given where rates are but perhaps the fed induced calm that has been engineered is coming to an end and the market is growing worried there is no put left - sorry for the essay

ReplyDeleteCameron: As I noted in my Jan 11th post (http://scottgrannis.blogspot.com/2018/01/worrying-about-rising-confidence.html), rising confidence is causing a decline in the demand for money (which is equivalent to a rise in money velocity). M2 growth has slowed dramatically (now only 1-2%), while nominal GDP growth is significantly faster (4-5%) than the growth of money. That means money velocity is turning up after years of decline. There is plenty of money to fuel a much bigger economy if this trend continues, and I believe it will. Rising confidence leads to rising money velocity, leads to more nominal GDP and possibly higher inflation if the Fed doesn't keep raising rates to keep the demand for bank reserves from declining. Fiscal stimulus is just beginning to kick in, and the result should be a big increase in the supply side of the economy. Demand will follow, as it always does ("supply creates its own demand", as the great French economist F. Say said long ago). Don't worry about demand, worry about supply (i.e., investment, jobs growth, productivity).

ReplyDeleteOne problem with explaining the declining productivity by saying "higher taxes and regulations," is that the decline has occurred globally.

ReplyDeleteWe have had tight central banks and loose labor markets, until very recently. And the metrics we use today may overstate labor market tightness.

The good news is I think we will see better productivity going forward, thanks in part to relative labor scarcity. The flavor is no longer cheap, it may make sense to invest in productivity enhancing technologies.

However I welcome any reduction in taxes and regulations, especially taxes on people who work for a living.

All in all another superb wrap-up by Scott Grannis.

Amatuer question? If supply creates demand in the economy, would that not by default imply an increased supply of safe assets creates a demand for safe assets?

ReplyDeleteMark: to answer your question, no. Producing safe assets like T-bills requires no labor. Nothing is produced save pieces of paper with promises attached to them.

ReplyDeleteWhen a person supplies his labor, or a business supplies its products to the economy, they have done something of value. When they realize that value (by selling or working), they own genuine resources as a result, and those resources (i.e., cash) can be used to buy (demand) other goods and services.