Since stronger economic growth dictates higher real interest rates, any concerns about higher interest rates negatively impacting the economy are premature. Higher interest rates are the natural result of stronger growth, as FOMC members have taken pains to explain. In any event, real yields are not even close to levels which might threaten growth. Moreover, there are still plenty of excess bank reserves in the system, and key indicators of market liquidity (e.g., swap and credit spreads) confirm that financial conditions are healthy. By all indications, the Fed is moving short-term rates higher in a healthy and non-threatening fashion.

Since early last year, there have been some profound changes in the US economy which augur well for the future. Perhaps the most important is increased confidence, which has largely replaced the risk-aversion that characterized most of the current recovery.

As I've argued many times over the years, the Fed's Quantitative Easing was a necessary response to the risk aversion that led to the world's almost insatiable demand for money and safety in the wake of the Great Recession. QE is no longer necessary now, so it is appropriate for the Fed to wind down QE by raising short-term interest rates and draining excess bank reserves. If the Fed weren't taking these steps, that would a source of concern, since they would be allowing a buildup of excess money which would inevitably find its way into much higher and unwanted inflation. To date, market-based measures of inflation expectations remain within reasonable levels, and that in turn confirms that the Fed is acting appropriately.

Here's a review of the vital signs of the economy and financial markets (all charts include latest data available as of time of posting):

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of the M2 money supply, which is widely considered to be the best measure of the amount of cash and readily-spendable cash equivalents in the economy (M2 consists of savings deposits, retail checking accounts, currency in circulation, small time deposits, and retail money market funds). M2 has been growing on average by 6-7% per year since 1960, and the most recent decade is no different, despite the Fed's alleged "money printing." As I've argued previously, QE was not about printing money, it was about transmogrifying notes and bonds into T-bill equivalents (aka bank reserves). Note, however, the recent slowdown in M2 growth; what looks like a moderate shortfall relative to trend is actually one of the most significant monetary developments in many years, as I explain below.

Chart #2

Chart #3

Chart #2 shows the level of bank savings deposits, whose growth was rather spectacular in the years following the Great Recession. Bank savings deposits represented about 50% of M2 in late 2008, and they now represent 66%, which is the highest level in recorded history. A terrified world deposited trillions of dollars in bank savings accounts, despite the fact that they paid almost no interest. Banks effectively used this huge inflow of funds to purchase notes and bonds and subsequently sell them to the Fed as part of the Fed's Quantitative Easing program. As Chart #3 shows, banks were happy to hold onto trillions of the bank reserves that the Fed used to pay for the notes and bonds it purchased. This was a direct reflection of the economy's increased demand for money and money equivalents.

Chart #4

Chart #5

Chart #6

Chart #7

Charts #6 and #7 show that to date the Fed has only pushed rates modestly higher. Chart #6 compares the current, inflation-adjusted overnight Fed funds rate (blue), which today is about zero, to the 5-yr real yield on TIPS, which is the market's estimate of what the blue line will average over the next 5 years, and which today is about 0.5%. Chart #7 shows the same real Fed funds rate as shown in Chart #6 in an historical context; note that real rates typically have been at least 3-4% before the onset of a recession. Chart #7 also shows the slope of the Treasury yield curve, which is typically flat or inverted prior to recessions (a flat or inverted curve is the bond market's way of saying it thinks the Fed has tightened enough or perhaps too much, and that lower rates thus lie ahead). Recessions typically happen when real borrowing costs are high and the yield curve is flat or inverted. Currently, we have neither such condition.

It's important here to note that prior to 2009, the only way the Fed could push short-term rates higher was by restricting the supply of bank reserves. Thus, monetary "tightening" involved not only higher interest rates but also a scarcity of liquidity in the banking system; at some point the combination of the two can be lethal. That's not the case at all today, as Chart #3 illustrates. Today, liquidity is plentiful, real borrowing costs are very low, and the yield curve is within "normal" ranges. The risk of recession is thus very low.

Chart #8

Chart #9

As Charts #8 and #9 show, inflation expectations over the next 5 and 10 years remain well within historical ranges (currently both are about 2.15%). The bond market is not concerned about either inflation or deflation or the Fed's ability to hit its 2% inflation target.

Chart #10

Chart #11

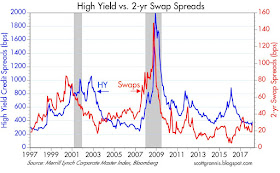

As Charts #10 and #11 show, swap and credit spreads are relatively low and very much in line with "normal" conditions. The market's expectations for growth and profitability are healthy.

Chart #12

Chart #13

Chart #12 shows that bank lending to small and medium-sized businesses has been stagnant of late, after reaching a relatively high level compared to the size of the economy. But as Chart #13 shows, the slowdown in lending has little or nothing to do with the health of borrowers; delinquency rates for all bank loans and leases are at historically low levels. Credit expansion is slow, but not because banks are actively restricting lending; rather, borrowers are less willing to borrow these days. That's a healthy situation, not a cause for concern.

Chart #14

Chart #15

Chart #16

Despite all the good news about financial market conditions and the economy, the market is still having trouble digesting the new reality of higher interest rates. But as Chart #16 suggests, the market has surmounted at least half of the recent "wall of worry." I would reiterate my earlier views that higher rates are not necessarily a bad thing—especially since they result from a stronger economy—but nevertheless higher rates pose competition for the earnings yield on stocks. Consequently, further gains in equity valuations are more likely to come from higher earnings than from expanding multiples. Total equity returns are likely to be decent going forward, but substantially less than we have seen in recent years, which is why I'm "moderately bullish."