As this chart shows, refinancing activity has been very strong and on the rise since early last year. I should know, as we are just finishing our second refi in the past 12 months. With a new 30-yr mortgage, our monthly payments will now be almost 30% less than they were a year ago. That frees up cash for all sorts of things, and if rates ever go back up, I'll feel like I've won the lottery. And if they should continue to fall, well then, I'll just refinance again. I keep thinking that someday I'll look back and congratulate myself for locking in a historically cheap rate (and tax deductible too!) on 30-yr money. There might never be another opportunity to borrow money at a fixed, after-tax cost of only 2-3%.

The other side to this coin is that the person lending me the money has seen a big reduction in his interest income. Actually, there is a massive amount of money all over the world that is being forced into lending at lower and lower interest rates. Most mortgages can be refinanced relatively easily when rates fall, but when rates rise, mortgages turn into long-maturity bonds because homeowners have a disincentive to move or refinance. Lenders thus see their MBS holdings behave like short-term deposits when rates fall, and like long-term bonds when rates rise—it's a painful experience.

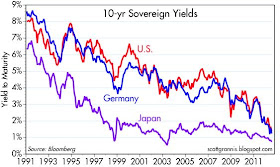

And it's not just in the U.S. that yields have collapsed. As the first chart above shows, 10-yr sovereign yields in the U.S. and Germany are rapidly approaching the super-low level of Japanese yields. Who would have believed this could happen? I've been dead wrong on my prediction several years ago that Treasury yields would be much higher than they are today. And it's not because inflation has dropped or that deflation threatens; inflation expectations embedded in TIPS and Treasury prices are firmly in the range of 2 - 2.5%, which is very much in line with what inflation has been over the past 10-15 years.

The world's major central banks are the proximate driving force behind the global yield plunge. As the chart above shows, they have pegged short-term rates to near-zero for over three years, and no one even hints at raising rates anytime soon. Why? Because markets and central bankers all believe that global growth is going to be very disappointing, and easy money is believed to be the only policy lever that might work to stimulate growth. Fiscal "stimulus" spending has been tried and it has failed. But never mind: as Treasury Secretary Geithner made clear in a speech today, "The economy is not growing fast enough. Unemployment is very high. There's a huge amount of damage left in the housing market. Americans are living with the scars of this crisis. The institutions with authority should be doing everything they can to try to make economic growth stronger ..."

Central banks can influence bond yields by the manner in which they target short-term interest rates and future expectations of short-term interest rates: if they say, as they have done for years now, that short-term rates will be kept low indefinitely in order to combat pervasive economic weakness, then yields all across the maturity spectrum will experience a strong gravitational pull downwards. The only thing that can push rates up is faster growth and/or a reversal of demands for policy stimulus.

What the history of low rates and disappointingly slow growth should tell us, however, is that easy money (e.g., very low short-term interest rates) doesn't stimulate growth. How are low interest rates going to create jobs, when fiscal deficits are gobbling up a gigantic amount of the global economy's resources? (One easy illustration of this is the billions of dollars that the U.S. government has poured into "green" industries that have yet to produce anything profitably.) In the U.S., our federal deficit has effectively absorbed every dime of total after-tax corporate profits for the last several years. Keeping interest rates low only facilitates government borrowing, while at the same time transferring wealth from savers to borrowers.

It's become a vicious circle of sorts: government spends more than it takes in and borrows the difference; excessive spending weakens the economy because much of it takes the form of transfer payments and inefficient spending; the weak economy prompts central banks to keep rates low; and lower rates facilitate more wasteful borrowing. Meanwhile, savers accept the lower rates because they have no confidence that things will improve; witness the huge, $2.3 trillion increase in savings deposits in the U.S. in the past four years that pay almost nothing.

Lower interest rates aren't going to stimulate the economy. They are better thought of as barometers for how weak the economy is perceived to be. This is not going to change in any meaningful way until policymakers—with the prodding of markets—realize that the way to get out of this vicious circle is to cut back on the size and scope of government. The sound and fury coming out of the Eurozone these days is all about this: governments and their constituencies fighting the efforts of markets to impose healthy fiscal discipline. The only countries where yields are rising are the ones (e.g., Spain) where markets see that spending and borrowing are on a collision course that can only end in tears. Fortunately, the bond market vigilantes have driven Spanish yields up to levels that will make it very difficult for the government to avoid the inevitable cuts in spending. This is how it should be.

"With a new 30-yr mortgage, our monthly payments will now be almost 30% less than they were a year ago. That frees up cash for all sorts of things, and if rates ever go back up, I'll feel like I've won the lottery."

ReplyDeleteIt surprises me you view real estate this way.

I doubt you will feel like you won the lottery if a rise in interest rates drops your house value by half. Or are interest rates and asset values no longer connected?

Whatever happened to the old saying that is better to buy cheap assets with expensive money rather than buy expensive assets with cheap money?

When you buy with high interest rates, you can always refi into lower rates and enjoy the asset appreciation ride. However you are advocating buying an expensive asset with low rates? What happens when rates go up?

The way I see it, interest rates are going to rise if and when the outlook for the economy improves. If the economy is doing better, than I expect that housing prices will firm and/or rise even as interest rates also rise. Higher interest rates won't be bad for the housing market, because they will reflect stronger economic fundamentals, which in turn will be a very welcome development.

ReplyDeleteI also view a 30-yr fixed rate mortgage as a very tax-efficient (and today, cheap) way of obtaining leverage, and for me, I think a prudent amount of leverage in my portfolio will be beneficial.

I much prefer the Dave Ramsey approach "where cash is king, debt is dumb and the paid off home mortgage has taken the place of the BMW as the status symbol of choice."

DeleteScott -

ReplyDeleteIsn't much of the recent move down in rates due to capital flight out of Europe? Ultimately it still comes down to supply and demand... the Fed can set short rates wherever they want but won't the long end keep them honest to some extent? What happens if a credible solution were to suddenly emerge out of Europe, say in the form of German acquiescence to Eurobonds...even with short rates pegged near zero here, I would expect a significant reversal in longer rates as much of that fleeing capital returns home.

To the first comment above -- We just bought a house and view it as buying a CHEAP asset with cheap money. According to our appraisal our house would cost 50% more than we paid to have it built today. And we paid exactly 50% less than what the previous owner paid to have the house built in 2004, before the bubble really got going. It would be tough to classify that as an expensive asset. And this is considered one of the most desirable locations in the country.

ReplyDeleteCapital flight out of the Eurozone is indeed occurring, but I doubt that it is seeking out 10-yr Treasuries; more likely it is going into shorter maturities. In any event, note that 10-yr yields here are almost identical to German 10-yr yields.

ReplyDeleteIf the Eurozone were to resolve its fundamental problems, I would indeed expect to see Treasury yields jump. The world is very concerned about a Eurozone disaster, and the Eurozone is flirting with recession already, and that is driving up demand for all sovereign debt, not just Treasuries.

I recently tried refinancing my home (which fell through for "technical" reasons related to a 2nd mortgage), but while going through the process it occurred to me:

ReplyDeleteRefinancing your house and the interest rate you pay on your mortgage make no difference.

Why? Because mortgage interest is tax-deductible! Over the course of a year, it makes no difference if I pay $1000 in mortgage interest or if I pay $1500 in mortgage interest. In both cases I will get the $1000 or $1500 back when I get my tax refund in the spring. If I refinance my house to a lower rate, I will get a "payback" in the form of a smaller tax refund. Essentially, the federal government pays your mortgage interest.

The only difference it *might* make is that you save money on mortgage payments each month, which will leave you a little more money to spend on other things. However, that might not really be a big deal: Either you spend the extra money a little bit at a time during the course of the year if you refinance your house, or you spend it all at once in the spring when you get a larger tax refund if you *don't* refinance your house. In the aggregate it makes little or no difference, it simply boils down to personal preference. In fact, given that you have to pay the bank for processing fees, refinancing your house could actually be a money-losing proposition.

As an aside, this is also one reason why those who said higher interest rates will kill the economy are wrong. At least when it comes to the housing market, it makes no difference.

unknown: you can only deduct a portion of your mortgage interest. So reducing your interest rate does increase your after-tax disposable income.

ReplyDeleteIn my case, I've been able to deduct *all* of my mortgage interest.

ReplyDeleteHere's the rules on mortgage interest deduction:

ReplyDeleteLINK

Essentially, if you took the mortgage out after 1987 (yes in my case), if the mortgage was just a straightforward loan to buy the house (yes in my case), and if the mortgage balance is $1 million or less (yes in my case), then it's 100% tax deductible. Clearly most mortgages these days are going to qualify for the 100% deduction.

Unknown -

ReplyDeleteYour interpretation is incorrect on that. 100% deductible is not the same thing as deducting 100% of your interest.

stated more clearly... itemized deductions come off the top line, not the bottom line.

ReplyDelete"Your interpretation is incorrect on that. 100% deductible is not the same thing as deducting 100% of your interest."

ReplyDeleteNot sure what you mean. Obviously I did not mean to say 100% of your mortgage is deductible, I was referring to 100% of the interest on your mortgage being deductible.

Last year I paid $10,784 in mortgage interest. Looking at my 1040 form right now, I subtracted the *whole thing* (plus another $1000+ in mortgage insurance premiums) from my adjusted gross income. The only "catch" to this is that I did this instead of using a standard deduction, but I can't think of any reason why anyone would use their standard deduction instead of itemizing, unless most of their house is paid off or it was an extremely inexpensive house.

You can deduct the full amount of mortgage interest paid, but that serves only to reduce your taxable income, and you "recover" only a portion of the interest.

ReplyDeleteExample: say you earn $100,000 and you have mortgage interest of $20,000, and you are in a 25% tax bracket. Without the mortgage interest you would owe $25,000 in taxes. With the mortgage interest deduction you would owe 0.25*(100,000-20,000)=$20,000. Thus you "save" or "recover" only one-fourth of your mortgage interest on an after-tax basis.

Now assume you refi and reduce your mortgage interest to $15,000. You will owe a bit more in taxes, 0.25*(100,000-15,000)=21,250, but you will have $3,750 more in your bank account. It pays to refi at a lower rate as long as the savings end up being greater than the costs of refinancing. In my latest refi, the breakeven point is a mere 5 months.

"Now assume you refi and reduce your mortgage interest to $15,000. You will owe a bit more in taxes, 0.25*(100,000-15,000)=21,250, but you will have $3,750 more in your bank account."

ReplyDeleteYou've lost me. You're comparing the post-refi number to the amount of taxes I would pay if I didn't deduct any mortgage interest at all (!!??). The point is to compare the pre-refi to the post-refi. The amount I would pay if I didn't deduct my mortgage interest at all is irrelevant, because in neither case am I going to do that.

In your example ...

No deduction = $25,000 in taxes

Pre-refi = $20,000 in taxes

Post-refi = $21,250 in taxes

Your $3,750 in "savings" is only because you're comparing it to the no-deduction scenario (25,000-21,250 = 3,750). But that's not under consideration because in no case was I going to *not* deduct my mortgage interest.

Unless I'm missing something else ...

It pains me that right-wing economic orthodoxy is so far wide of the mark, and out own Scott Grannis, who is usually so perceptive.

ReplyDeleteThe world is awash in capital. Every Treasury auction is oversubscribed. There is no "crowding out," the 1960s-1970s phenomenon of the US government taking up much of the available capital. We have a global economy, and savings rates are high all through Asia, and much of the world.

In the 1960s-70s, the USA was nearly an island economy--trade and foreign capital were rather limited, in relation to the entire economy.

That is not the case today, with profound ramifications for goods, services and capital markets. Labor too, although we (the GOP especially) seem intent in closing our nation to hard-working immigrants.

Japanonomics is what you are seeing in the USA. I agree that federal deficits are not useful.

Japan had its longest postwar expansion from 2002-2008, when it was undergoing a QE program. Slow growth, but steady. And no inflation.

With interest rates going down to zero--and Grannis' own charts show that trend is decades old and global, and so it not the province of Obama, Bush jr, or anyone else--a key policy tool of central banks has been obliterated.

Central banks can't stimulate the global economy by lower rates, once the conventional means. That is in the past.

Think about it. If interest rates decline globally for decades, you think there is any case to be made that "crowding out" is going on? Surely, there is a root cause to declining global interest rates. High savings rates? Central bank actions to wipe out inflation?

In any rate, the trend has played out, and we will be at zero perhaps permanently, as they are in Japan. The Cleveland Fed inflation anticipation figs says we are here for the next 10 years.

QE is what is needed now, on a sustained basis, while we bring the federal budget under control.

BTW, I get a kick out of right-wingers when they condemn federal energy programs, especially renewable fuels. I agree, btw.

Scott Grannis: "(One easy illustration of this is the billions of dollars that the U.S. government has poured into "green" industries that have yet to produce anything profitably.)"

Of course, by far the largest, most subsidized, mandated, federalized and socialist renewable federal energy program is...ethanol. Shhhh.

Grannis dare not mention it by name. It is GOP moonshine.

Obama's silly little green programs are puny in comparison to ethanol, and much smaller in terms of being structural impediments.

Ethanol is national, 10 percent of every gas tank in America, unless it is 85 percent. Corn farmers are still subsidized with your tax dollars, and the use of ethanol is mandated by federal diktat. Nationally.

The mistake solar power dudes have made is not getting under the wing of the USDA, and to say they are harvesting sunlight in rural America. With permanent subsidies and mandated markets, and a few decades, they would have become so embedded in the economy and tight with the GOP they would have been a permanent feature of our economy too.

Benji,

ReplyDelete"Grannis dare not mention it by name. It is GOP moonshine. "

Have you a shred of proof Scott supports ethanol? On the other hand, we know Obama, whom you enthusiastically voted for, is a big Big Ag booster as are pretty much all farm state Democrats all across the midwest.

Obama, along with being the green energy swindle president, is also the food stamp president. 80% of the 2012 farm bill will be spent on the massively-expanded-under-Obama food stamp program, yet I never see you wetting your pants over that.

Scott, what costs, percentage of loan amount refinanced, did you outlay, on each of your refinances, for points, appraisals, closing costs, etc.,.

ReplyDeleteI see you are financing strategy is right out of the Treasurer's Handbook--borrowing for as long as you can, as long as you can, even though you will probably not 'outlive' your mortgage, as opposed to doing a ten year fully amortizing loan at a better rate.

I'm considering on the next re-fi, going back to a longer maturity (30 year versus the current fifteen), and enjoying, and reinvesting, the monthly savings at a higher rate, into fixed income instruments.

Paul-

ReplyDeleteI doubt Scott Grannis supports the ethanol program--it would be inconsistent with his admiration (and mine) of free markets.

However, he seems to believe (as do you) that silly renewable energy programs are the sole province of the left-wing in the USA.

On the contrary, the biggest, inbred, feeble, greenie-weenie, socialist, mandated, subsidized energy program, and largest structural impediment is our ethanol program, which largely blossomed under President Bush jr.

Bush defends ethanol emphasis

THE NATION

The corn biofuel isn't the main cause of high food prices, he says, and the U.S. should be 'growing energy.'

May 03, 2008 The Los Angeles Times

"As you know, I'm a ethanol person," he said, explaining his belief that it can help reduce U.S. dependence on oil. "It makes sense for America to be growing energy."

At that time ethanol was directly subsidized and mandated in use. Now, it is "only" corn farmers who are subsidized, while use is still enforced by federal diktat.

Of course, Bush jr, also brought us Medicare Part B ( a larger liability than Social Security), two unfinished but vastly expensive wars, and a permanent explosion in the federal security state--and a doubling of defense outlays, in real terms.

Romney, btw, says we need to enlarge federal spending in the military.

As for Obama, I held my nose and voted for him, and my last enthusiastic vote was for...Bush jr. (the first time). I thought he was a guy with an MBA and not an ideologue.

Instead, his administration was a train wreck into a sewage treatment plant.

Unknown, there are two factors that could influence a 'difference' between the two scenarios:

ReplyDeleteThe amount of loan being paid

The rate of tax to apply

It is possible that two different rates apply when comparing large differences in deductible interest being paid.

Any deduction is worth the applicable tax rate times the deductible interest amount as a cash equivalent.

Any reduction in a mortgage payment is also a cash equivalent.

Generally, if a refinance involves a point or more of interest rate, the cash from reduced mortgage rate is larger than the cash generated by the deduction difference.

Scott is correct. There normally is a difference.

I suppose I might not have been looking at it right ... but refinancing would have saved me about $100/month in mortgage payments, which would be $1200/year, and though I didn't get far enough in the process to be able to do the calculation, it seemed to me the greater taxes I would pay due to a smaller deduction would do little more than even out the $1200/month I would save in monthly payments.

ReplyDeleteBenji,

ReplyDelete"However, he seems to believe (as do you) that silly renewable energy programs are the sole province of the left-wing in the USA."

Unbelievable. Once again: you are the one blaming ethanol all on one party. Obama was a huge booster of ethanol, as are

all farm state Democrats I can think of, yet you continue again and again with the brazen lie it's all "GOP moonshine."

Liar.

Paul-

ReplyDeleteUSDA and DOE select 13 biofuels projects for more than $41M in awards

26 July 2012

The US Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Energy (DOE) will award $41 million investment to 13 projects to drive more efficient biofuels production and feedstock improvements through genomics.

Through the joint Biomass Research and Development Initiative (BRDI), USDA and the DOE are working to develop economically and environmentally sustainable sources of renewable biomass and increase the availability of renewable fuels and biobased products. Five projects newly selected will help to replace the need for gasoline and diesel in vehicles. The cost-shared projects include: