Here are some charts which recap my argument that there is no evidence that liquidity is in short supply, and thus no need for further quantitative easing from the Fed.

Swap spreads are excellent indicators of systemic risk, which can be aggravated by an effective shortage of liquidity. At 26 bps, 2-yr swap spreads reflect no sign of any such liquidity shortage. Swap spreads at current levels are fully consistent with "normal" liquidity conditions.

The dollar is up on the margin since last summer, but it is still very low from an historical perspective. If dollars were in short supply, the dollar would likely be a lot stronger.

Even with today's $35 drop, gold prices are still extremely high, both from a nominal and a real perspective (the average price of gold over the past century in today's dollars is about $500/oz.) Gold is a very sensitive indicator of monetary imbalances, and today's selloff comes not as result of a future shortage of money, but rather from the fact that the market is now expecting monetary policy to be less easy—but still very easy—than previously expected.

Commercial and Industrial Loans are growing at double-digit rates. Banks are lending to small and medium-sized businesses once again, and business is booming on the margin. No sign here of any need for the Fed to push harder on the monetary accelerator.

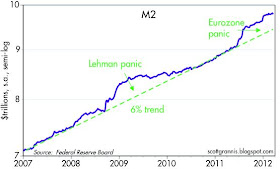

Growth in the M2 measure of the money supply has been abundant. The Fed has eased monetary conditions in response to surging demand for liquidity—as it should—but in the absence of further shocks there is no reason for further easing measures. In the meantime, there are trillions of dollars of cash (savings deposits at U.S. banks have increase by more than $2 trillion in the past 3 1/2 years) sitting on the sidelines that have the potential to "reflate" the economy as confidence improves.

Commodity prices are still off their recent highs, but they have been rising for the past 3-4 months and they are generally higher today than they were prior to the last recession. The collapse of commodity prices in 2008 was good evidence that the Fed was slow in easing policy in response to the financial crisis, but the recent drop looks much more benign. Moreover, oil prices remain quite strong, and gasoline prices continue to rise. If anything, the behavior of commodity prices is more consistent with an abundance of liquidity (i.e., monetary policy that is very loose) than with any shortage of liquidity. Since the Fed started easing in 2001, commodity prices by this measure are up over 140%.

This chart compares the spread between 2- and 30-yr Treasuries (a good measure of the steepness of the yield curve) with the inflation expectations embedded in Treasury yields. Both have been rising for the past several months, an indication that liquidity conditions actually have been easing. The market essentially has been realizing for months now that what the Fed was doing (by keeping short-term rates very low for an extended period) was effectively increasing the supply of liquidity to the market. Again, no reason for the Fed to do more than it is already doing.

More or less dollar liquidity is irrelevant at this point -- the end of the dollar (Federal Reserve Notes) is near -- I expect that dollars will be replaced with other currencies within a decade -- electronic currencies are not the same as Federal Reserve Notes -- the sunset of the US Federal Reserve Note is now underway...

ReplyDeleteAutomotive News is reporting March's auto sales SAAR at 14.4 million. However, Business Insider is saying it's 15.2 million. Looks like no one is sure what this month's seasonal adjustment is.

ReplyDeleteBut in either case it's a good number.

Business Insider just changed its mind. I think maybe they forgot to adjust for the extra selling day this year. 14.4 million looks to be the correct number. Still good though.

ReplyDeleteThe dollar trading range is now where it was in 1993 or so. So we can say it is high or normal or low.

ReplyDeleteNo one claims the Fed was loose from late 1980s to mid-1990s, yet the dollar lost one-third of its exchange value then. Why?

If the dollar's exchange rate means a lot, why did it fall all the way through the Bush Administration, and then firm up under Obama? This would indicate the Fed tried to help Bush with easy money, and then started to get tight under Obama. Really? Or that the investing public "believes in the dollar" with Obama at the helm. I doubt that.

There are times when formerly classic signals fail, due to fundamental shifts underlying assumptions.

No doubt, there are plenty of capital today left on the sidelines--we have a global capital glut, the same situation faced by Japan.

The Keynesians say you have to have a government borrow that money and spend it, sparking a recovery. But that was tried in Japan and it didn't work. They went to 200 percent public debt-to-GDP, and still interest rates are zero. That is also not what the John Cochranes of the world predicted either. Japan is supposed to suffering from runaway inflation, if you believe John Cochrane. But they are not. In fact they suffer from chronic deflation. Have John Cochrane explain that, or any Western economist. Huge perennial chronic federal deficits and deflation.

So, we can we do? "Nothing" is what some say, but then we are somewhat doing a meek version of the Japan model. Big fiscal deficits and tight money. That is our policy also.

The United States of Nippon.

Milton Friedman taught us not to associate low interest rates with loose money. Low interest rates are a sign of tight money.

The Fed is making a mistake. Not only do we need QE, we also need sustained QE, with a publicly target of nominal GDP growth of perhaps 7 percent annually for several years. $100 billion a month of QE (purely buying government bonds) might do the trick. Friedman said such QE would inevitably lead to economic growth and then inflation. That is why he told Japan to go hot and heavy into QE.

Milton Friedman, John Taylor, Ben Bernanke, Alan Meltzer, Frederic Mishkin all recommended QE to Japan. Not one expressed any reservations about debasing the currency, exchange rates or monetizing the debt. Those seem to be the concern of the gold-nut blogger crowd, but no serious economist.

The USA economy is recovering, but in some ways not. The fraction of our population productively employed is sinking. About one out every 20 people you meet used to work, but does not now.

Well, we can also achieve what the Japanese have: No inflation, even though potential output of the economy is cranked down every year.

Gold managed to rise in the 2004-2006 period during which the Fed raised rates. And the Fed isn't yet even talking of raising rates.

ReplyDelete@Benjamin, monetary expansion in the US is on hold indefinitely -- the austerity hawks won the battle, which means austerity is coming -- I suspect the war hawks will win as well, which means world war -- better to ponder 1936 and exploit the situation to your own benefit -- more than a few smart business people saw what was happening and got rich in the late 1930's and 1940's...

ReplyDeleteDr McKibben--

ReplyDeletejohn Taylor just reviewed Robert Hetzel's new book and like it.

This means John Taylor is getting on board with Market Monetarism--if Romney wins.

My guess is that if Romney wins, you won't hear any more sniveling from the right wing or GOP about inflation or the Fed. The Fed will be told to print a lot more money.

As for war, who knows. Who would have through that Bush jr, would have committed us to $4 trillion and more than a decade of useless wars. I would not have voted for him, had I known that.

Romney is now braying about the need to show American might, beat the Russians and spend even more on our military. Such incredible waste and coprolite.

I wish I had another party to vote for.

"There are times when formerly classic signals fail, due to fundamental shifts underlying assumptions."

ReplyDeleteVery true. We need to consider other metrics and develop new ones.

A sincere question for Scott Grannis:

ReplyDeleteOkay, you say we have liquidity in the USA, so no more QE.

They have liquidity in Japan, and they have mild deflation and zero interest rates.

The yen is very strong.

Ergo, just having liquidity, and low interest rates does not mean money policy is loose---otherwise, how has Japan's yen risen so much?

How do you explain a rising yen in a nation with abundant liquidity and zero interest rates?

"The Fed is making a mistake. Not only do we need QE, we also need sustained QE, with a publicly target of nominal GDP growth of perhaps 7 percent annually for several years-"

ReplyDeleteBen Jamin, could you explain why America needs continued simulation, with an economy growing at a reported rate of 3%+?

Also is it possible for you to restrain the use of Japan as a constant example?