Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Thoughts on monetary policy and productivity

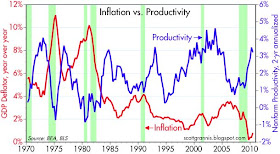

Using the latest productivity numbers (productivity was down slightly in Q2/10, after having risen very strongly for the previous five quarters) and the latest GDP revisions, I've updated this chart that has been a long-time favorite of mine. The blue line represents the running 2-yr annualized growth rate in nonfarm productivity (this smooths out the typically volatile quarter-to-quarter changes), while the red line represents the year over year inflation rate as measured by the GDP deflator, which in turn is the broadest measure of inflation available.

What the chart purports to show is that there is a strong tendency for productivity and inflation to move inversely. Periods of declining and low inflation tend to be periods during which productivity is rising and generally strong—with the 1995-2003 period being a classic example. Periods of rising and high inflation tend to be periods during which productivity is volatile and generally low—with the 1970s being the classic example.

This relationship holds, I believe, because low inflation tends to focus people's attention on productive investments at the same time it promotes confidence by delivering stability, while high inflation tends to encourage speculative investments and discourage investment because it increases uncertainty. If prices are generally stable, for example, then it is difficult to make money by buying commodities, and the only real game in town is making money the hard way, by working harder and doing things more efficiently. If on the other hand prices are rising, then it becomes easier to make money by speculating in commodities, and it becomes very difficult to work more efficiently or to take on long-term investments because one loses confidence in the future. During the 4 years I lived in Argentina the inflation rate was well over 100% per year, and I can personally vouch for the fact that investment horizons shrink dramatically as inflation rises, and the business of life eventually becomes reduced to survival rather than planning and saving for the future.

I note that the chart is suggesting (still early to call this for sure, but it's tempting nonetheless) that we could be entering a new period of rising inflation and declining productivity. That's essentially the scenario I've been calling for since early last year—rising inflation and a subpar recovery.

How would this work? Easy money is likely to give us rising inflation, while oppressive government (e.g., the 25% increase in federal spending relative to GDP that Obama's budget is projecting) is likely to give us declining productivity.

I raise this issue because it is timely, with all the talk these days focused on the economy's presumed "loss of momentum" in the past several months. Most observers want the Fed to take steps to make money cheaper and for a longer period, in the belief that the economy is being starved for liquidity and the banking system is failing to pump out loans. From my perspective the Fed is not the culprit, if indeed the economy is losing momentum and slowing down. The Fed's easy money has helped commodity prices rise impressively, and the trillion dollars of bank reserves that are currently sitting idle at the Fed send shivers up the spine of investors and businesses everywhere, as we worry about the endgame of this unprecedented experiment in quantitative easing. I think easy money is part of the problem, not the solution. The op-ed in today's WSJ, "The False Fed Savior," agrees with me.

Monetarists, classical economists, and supply-siders all believe that monetary policy is essentially powerless to create growth out of thin air. You can't print your way to prosperity, since pumping unwanted money into the economy only creates inflation, not growth. In the same vein, monetary policy is a very poor tool for fine-tuning economic growth. Monetary policy tends to be a blunt instrument: the Fed tightens policy in order to fight inflation, and eventually policy becomes so tight that the economy falls into a recession—that's been the story of every post-war recession with the possible exception of the last recession. Monetary policy can become an obstacle or impediment to growth if it is incorrectly managed, but it can't call up growth from the ether. Good monetary policy can facilitate growth because it inspires confidence and that results in more investment and risk-taking, while bad monetary policy can kill growth because it creates uncertainty and that can shut down investment.

So I would like to see the Fed address its limitations today, rather than launch some new QE2 program. Ideally, the Fed should point the finger at Congress, since fiscal policy has been and promises to be a huge obstacle to progress. Only a more business-friendly and investor-friendly shift in fiscal policy can brighten the outlook for growth. The Fed can't and shouldn't try to do more than it has already.

As always, I agree with the sentiments for lower taxes and regulations.

ReplyDeleteBut Richard Fisher's awful editorial in today's WSJ is cheap political pandering at the expense of thoughtful and brave monetary policy.

Fisher evidently believes that a Fed regional presidency is a platform to espouse right-wing nostrums. I welcome his cheap posturing as much as I would another regional President advocating for national health insurance to promote healthy and productive workers. Oddly enough, Fisher's top economist is an Argentine who wears deeply polished boots.

At worst, Fisher appears to be holding proper monetary policy hostage until the right-wing gets the tax and reg policies it wants. Oh, great.

I wonder what commodities prices tell us anymore. Russia is burning to hell, so wheat prices will skyrocket--our Fed is too loose? Oil prices are determined by a loose confederation of thug states. Gold is hot in India and China, largely for cultural reasons, and they have rising incomes. It is a fever too. In short, commodities have become global markets, reacting to global demand and monetary policies.

I fear the Fed is going to guide us into deflation--a bad trap, and one wonders what will get us out.

Not Fisher--until a Republican is elected, anyway.

I 150% agree. This is 100% agreement with cheap money leverage!

ReplyDeleteHi Scott, welcome back. I enjoyed reading your posts from Africa. Looks like you and Norma had an amazing trip. Cant wait to see more pics :)

ReplyDeleteI read this today in the comments section of a WSJ article and thought it was worth resonating: (copy/pasted)

1. You cannot legislate the poor into prosperity, by legislating the wealth out of prosperity.

2. What one person receives without working for, another person must work for without receiving.

3. The government cannot give to anybody anything that the government does not first take from somebody else.

4. When half of the people get the idea that they do not have to work because the other half is going to take care of them, and when the other half gets the idea that it does no good to work, because somebody else is going to get what they work for, that my dear friend, is the beginning of the end of any nation.

5. You cannot multiply wealth by dividing it.

For someone from the outside looking in, this seems to be the case.

Daniel:

ReplyDeleteI lived in Singapore where there is no social safety net, everything is provided by the individual, the result saving rate in excess of 40%. It should be noted that 30% of all Singaporean income is automatically saved into a provident fund (yeah individuals don't control the cash).

Taking your view that an unearned dollar to support the unemployed is a wasted dollar, it follows that American would have to follow the example of Singapore, China, Indonesia and Malaysia -- which all require this automatic savings scheme.

Not saying you are wrong, but a savings rate of 40% would dramatically change the American economic landscape.

If the solution is to let people starve, turn-off street lamps, then instead of unemployment benefits you end up with large prisons.

Bottom line there is today 6 unemployed for every available job, so by definition five of the six unemployed will be disappointed. What is your policy, ship them out of your state or the country?

the social safety net is an important component of the social contract in America, to say that the safety net is a waste is false.

Its a bit like saying that car insurance is useless!

Scott:

ReplyDeleteI suspect that Ben & friends have figured out that further QE is a waste of money. The Feds have the numbers and the "bang for the bucks" from QEI has been poor, and the likelihood that a new round would do any better has to be viewed with skepticism (even Obama can do math).

The Feds probably know that its a balance sheet recession, and that there are very few tools the Feds can deploy to support the economy.

Today's Fed statement is a clear signal that QEII is not on (yet). As for the fall in productivity good question, but since most people don't know what are the productivity drivers (i.e. they know what makes productivity rise, nobody knows how to stimulated these drivers)I just don't buy the lower tax and lower regulation as the solution to entice companies to invest more. Final demand is the problem, as long as that problem is not resolved there is no easy exits.