Sunday, January 31, 2010

Tea Party update

The Tea Party movement is alive and well. I remember attending my first Tea Party gathering last April 15, and now the movement is organizing and preparing to announce its Contract From America this coming April 15th. Glenn Reynolds has a good article that explains what's going on here. You can vote on what you think should be the elements of the Contract From America here.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

The Obama Contradiction

That's the title of a nice essay by Peggy Noonan in today's WSJ that talks about Obama's State of the Union speech. I've pulled out the best parts here:

President Obama's speech was not a pivot, a lunge or a plunge. It was a little of this and a little of that, a groping toward a place where the president might successfully stand. Speeches are not magic, and this one did not rescue him from his political predicament, but it did allow him to live to fight another day.

The central fact of the speech was the contradiction at its heart. It repeatedly asserted that Washington is the answer to everything. At the same time it painted a picture of Washington as a sick and broken place. It was a speech that argued against itself: You need us to heal you. Don't trust us, we think of no one but ourselves.

Why would anyone have faith in that thing to help anyone do anything?

Why [she asked a friend] did the president not move decisively to the political center?

Because he is more "intellectually honest" than that, he said. "I don't think he can do a Bill Clinton pivot, because he's not a pragmatist, he's an ideologue. He's a community organizer. "

"I hope we have big changes in 2010," the friend said. Only significant loss will force the president to focus on spending. "To heal our country we need to get the arrogance out of the White House and the elitists out of the Congress. We need tough love. We need a real adult in the White House because we don't have adults in the Congress."

Friday, January 29, 2010

My personal FDA rant

Yesterday I discovered that the FDA is barring me from obtaining software that might significantly improve my hearing. Bizarre as that may sound it's true.

My hearing ability is entirely dependent on a small but powerful signal processor that feeds about 1 MB of data per second through my scalp to an implanted device that in turn sends an electrical signal to my cochlea. (See a detailed explanation of cochlear implants here.) The manufacturer of my device has developed a new processing algorithm for the signal processor that, according to studies already done in Europe and Canada, results in a 50% increase in most people's ability to distinguish speech in a noisy environment. Since noise is the #1 enemy of everyone who lives with a cochlear implant, this is fantastic news.

Implant users in Europe and Canada are already benefiting from this new software, but here in the U.S., the lengthy FDA approval process is just getting started. It's likely to take at least a year before the FDA decides that this software is safe enough for me to use.

My first reaction to this news was "wow, this could be really great!" My second reaction was "what possible health risk could there be in an updated version of software?" Why is the FDA getting involved in this in the first place? Why can't I get it right now? Upon further reflection, I am now wondering where in the Constitution it says that the federal government can dictate to me what process or software I use to hear?

This is just one small, tiny example of what happens to individual liberties when the State expands in size and scope. It's outrageous.

My hearing ability is entirely dependent on a small but powerful signal processor that feeds about 1 MB of data per second through my scalp to an implanted device that in turn sends an electrical signal to my cochlea. (See a detailed explanation of cochlear implants here.) The manufacturer of my device has developed a new processing algorithm for the signal processor that, according to studies already done in Europe and Canada, results in a 50% increase in most people's ability to distinguish speech in a noisy environment. Since noise is the #1 enemy of everyone who lives with a cochlear implant, this is fantastic news.

Implant users in Europe and Canada are already benefiting from this new software, but here in the U.S., the lengthy FDA approval process is just getting started. It's likely to take at least a year before the FDA decides that this software is safe enough for me to use.

My first reaction to this news was "wow, this could be really great!" My second reaction was "what possible health risk could there be in an updated version of software?" Why is the FDA getting involved in this in the first place? Why can't I get it right now? Upon further reflection, I am now wondering where in the Constitution it says that the federal government can dictate to me what process or software I use to hear?

This is just one small, tiny example of what happens to individual liberties when the State expands in size and scope. It's outrageous.

Money velocity: the macro driver of GDP

I've read lots of commentary about what caused the larger-than-expected increase in GDP in the fourth quarter. Most observers note that the main driver of the 5.7% annualized growth rate was a decline in the pace of inventory liquidation, which contributed 3.4%. From this they conclude that the economy's strength was not that impressive, especially considering that the growth in personal consumption expenditures only contributed 1.4%. This may explain the market's weakness today.

I'm going to step above the fray and look at one of the macro sources of the growth in GDP. The one that immediately jumps out is the velocity of M2. (The inverse of velocity, i.e., the demand for money, is shown in the second chart above.) Money velocity rose in the fourth quarter at an annualized rate of 2.9% (and the demand for money fell by a similar amount). Some of the money that people had hoarded in the previous year (under the mattress, in money market accounts, or in bank deposits) was taken out and spent in the fourth quarter. This is the physical manifestation of a general rise in confidence; people came to realize that the precautionary money balances that they had built up were more than enough given all the signs of improvement in the economy. If this process were to continue until money demand returned to where it was pre-crisis, that would add a whopping 13% to GDP (assuming M2 doesn't decline in the interim).

One thing helping this process is the Fed. By keeping short-term interest rates close to zero, the Fed is trying desperately to convince people that they don't need all the money that they have been holding onto. It was the huge increase in the demand for money that prompted the Fed to expand its balance by purchasing $1 trillion of Treasuries and MBS; the Fed was simply reacting, as it should, to an unprecedented increase in the demand for money. As the demand for money declines further, the Fed will sooner or later be able to withdraw its injections of reserves into the banking system, and that needn't result in any major economic dislocations. What might happen, of course, is that the Fed may well decide to wait too long to reverse course, in which case we would end up with higher-than-expected inflation.

The other thing helping this process is the recovery itself. Note in the second chart that money demand usually tends to decline after a recession. Money demand rises in advance of and in the early stages of recession, reflecting rising fears and the demand for precautionary balances. It then declines as animal spirits return. This process was particularly intense in the recent recession, since it was mainly a financial-panic-induced recession. As the recovery progresses and confidence returns, the demand for money has plenty of room to decline (i.e., money velocity has plenty of room to rise), and this will be an important source of growth in nominal GDP in the years to come.

A final note: rising M2 velocity can actually do two things to GDP: it can increase nominal GDP and/or real GDP. So far it has mainly contributed to propel real GDP higher (since the GDP deflator has been less than 1% in the third and fourth quarters), but rising velocity could certainly contribute to a rise in the general price level at some point in the future.

Another V-sign: Chicago Purchasing Managers' Index

I don't ordinarily pay much attention to the regional components of the Purchasing Manager's index (published by the Institute for Supply Management on the first day of each month), but the Chicago index published today was such a great example of how dramatically things have changed over the past year that I couldn't resist adding it to the list of V-shaped recovery signs. It's not surprising at all that GDP grew at a 5.7% annualized pace in the fourth quarter. The recession is definitely over, and the only issue going forward is how strong the recovery will be. I'm in the camp that says we'll see 3-4% on average this year and next, but the consensus (the "new normal") seems to be calling for 2-2.5%. I think the consensus is too pessimistic; even my 3-4% represents a fairly anemic recovery, given the depth of the downturn we've just lived through.

I'm calling for a sub-par recovery because of all the wasteful government spending that is going to drain productive resources from the economy. You can't just take money from the bond market and hand it out to people in the form of subsidies and expect that to stimulate the economy. Economies grow only when people are working harder and/or producing more. True real growth thus requires hard work and investment, not just handing out money and putting people to work on projects that the private sector has already decided aren't very productive. If we want a truly impressive recovery, we'll need to cancel the stimulus spending, restructure and reduce entitlement programs, shrink government programs in general, and lower tax rates across the board.

Australian dollar update

I post this to follow up on a question from a reader concerning the advisability of investing in Australia. The main risk I see is that everyone loves Australia right now, and that's why the currency is about as strong relative to the U.S. dollar as it has ever been. If you are a U.S. investor putting money to work in Australia today, the price of admission is very high. That's not to say the investment doesn't make sense, just that the relative value of the investment is not terribly attractive, and there is the potential for significant downside currency risk.

To explain the chart: the blue line is simply the Aussie dollar exchange rate, while the green line is what I calculate the purchasing power parity (PPP) of the exchange rate to be over time. The PPP calculation takes account of the differential in inflation between Australia and the U.S., and it is theoretically the value of the currency that would make a given basket of goods and services cost the same in both countries. With the blue line exceeding the green line by a wide margin, this means that a U.S. visitor to Australia is likely to find that most things are expensive relative to what they cost in the U.S.

The downtrend evident in the PPP line means that Australian inflation has tended to be higher than U.S. inflation, so the currency therefore has a tendency to trend lower over time against the dollar. This may of course change in the future, and that wouldn't be impossible at all, especially considering that the Aussie central bank has already tightened monetary policy but the Fed is many months away from doing so.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Let's not miss the fiscal forest for the deficit trees

Ed Lazear, an excellent economist who also has Washington experience, has a great article in today's WSJ that puts taxes, spending and deficits into sharp focus. Like me, he agrees with Milton Friedman that it's not the deficit that really matters, it's the level of spending. Obama & Co. have been working very hard to camouflage the huge increase in government spending they are promoting by insisting that they won't grow the deficit. But that of course means that they plan to grow taxes—by a lot. The chart above highlights the stakes involved, and is a useful companion to Lazear's article.

Today both spending and tax revenues are in uncharted post-war territory. Tax revenue as a % of GDP hasn't been this low on a sustained basis since the early 1940s. Spending relative to the economy hasn't been this high since the wartime expenditures of the early 1940s.

Here are some highlights from his article:

My analysis of data from 1950 to the present shows that periods with high tax-to-GDP ratios exhibit much slower economic growth than lower tax ratio periods. The GDP growth in high tax years (defined as years during which the ratio of tax-to-GDP was above 18%, the 60-year average) was about 1.5 percentage points lower than the growth rate in low-tax years.

High taxes are clearly bad for the U.S. economy. For example, were we to tax above the 18% tax-to-GDP ratio over the next 25 years, GDP per capita in 2035 would be about 50% less than if we were to tax below the 18% ratio. A 50% per capita GDP differential is about as large as the difference between the U.S. and Greece today.

The recent growth in spending has been camouflaged by a focus on deficits. Budgets and proposed legislation, like that on health care, are being judged not by their impact on spending and taxation, but by their projected effect on the deficit. Equal increases in spending and taxes reduce economic growth, even if they do not alter the deficit.

So the rhetoric surrounding the health-care bills misses this point. Were they to pass, it would mean more spending, more taxes and less growth.

It will be virtually impossible for Mr. Obama to keep his promise not to raise taxes on the middle class while paying for an enormous increase in spending. Given the planned spending levels, taxes will have to rise substantially to get to the target 4% deficit figure that the White House wants.

Capital goods orders continue to rebound

This is very positive. Capital goods orders have risen at a 19% annual rate since bottoming last April. This reflects rising confidence on the part of businesses, and it's new investment that will help raise the productivity of workers in the future. Orders are still relatively low from an historical perspective, but they are definitely going up, and that is a very positive change on the margin.

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Why I still like AAPL

I first recommended AAPL on this blog just over a year ago, when the stock was around $80-85. I've owned the stock since 2002 and have no plans to sell.

Apple unveiled its new iPad this morning, and I'm seeing some mixed reviews. I'll have to hold it in my own hands to say whether it's really "magical" as Steve Jobs claims. Some were disappointed that it doesn't have a camera, or multitasking. No hand-held videoconferencing ... but maybe that comes with the next version.

But the iPad does offer a lot more than anything else in the netbook or tablet category, and it leverages all of the software that drives the iPhone and iPod Touch, plus the market-dominating iTunes, the iTunes store, and the App Store. The killer feature, I think, is that you get all kinds of great stuff that we know works well with an entry-level price of only $499. Not many will be able to resist this. It does far more than a Kindle for only a little more $$. It's a new portable gaming platform that already has thousands of games ready to go on day one (iPhone games will run today on the iPad in reduced size, but it should be relatively easy for developers to tweak their apps to take full advantage of the bigger screen). You can use it to generate presentations that make Powerpoint slides look pedestrian, and you can plug it into any projector. It weighs only 1.5 lbs., so many people will undoubtedly want to travel with it. Read books, watch HD movies, play great games, surf the web, do email, etc. Once again Apple has blown away its competitors and created a new product with sex appeal.

The second chart above compares Apple's market cap to Microsoft's. It's the David vs. Goliath story of our time. Apple is still worth about $75 billion less than Microsoft, but Microsoft has almost 90% of the worldwide market for personal computers. That's a testament to how Apple has opened up new markets and innovated like no other company in recent memory. And Apple can still grow its share of the personal computer market by leaps and bounds, as it has been doing for the past 5-6 years. If you haven't tried a Mac computer, you don't know what you're missing.

What housing market weakness?

I keep seeing references to the "renewed weakness" in the housing market, which is supposedly revealed in the recent decline in new home sales, housing starts, mortgage apps and refis. But this chart, which is a cap-weighted index of the equities of major American homebuilders, shows that the market's outlook for the residential construction sector hasn't changed at all since last August. Yes, we've seen a drop in home sales, but that came on the heels of a significant rise. New home sales, existing home sales, building permits, and housing starts are all still up over the past year, despite some recent weakness. The market may be looking for an excuse for a correction, but I don't see any sign of legitimate or emerging weakness.

Misery Index update

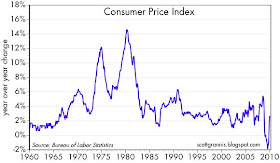

On the eve of Obama's first State of the Union address, it's appropriate to update this chart that was first made popular by Jimmy Carter while running for the presidency in 1976. While emphasizing the economic mess that was the legacy of the Nixon and Ford administrations (rising unemployment and rising inflation) likely helped Carter win the '76 election, the Misery Index came back to haunt him by soaring to 22 during the summer of election year 1980. Though not an exact parallel, Obama now faces the wrath of voters as the Misery Index stands at 12.8 (10% unemployment plus 2.8% inflation), its highest level since 1983. This looks especially bad since he promised a year ago that spending $1 trillion in stimulus funds would keep the unemployment rate from rising above 8%.

To make matters worse, today the CBO said that the unemployment rate will likely exceed 10% for the first half of this year and average 10% in the fourth quarter of this year. Meanwhile, by my estimates, the year over year change in the CPI could reach 3.5% by mid-year, and that would combine to push the Misery Index up to almost 14. Not a pretty picture at all.

I'm reminded of Reagan's prescription for taming the miserable Misery Index he inherited: significant marginal tax cuts to boost the economy, and very tight monetary policy to bring inflation down. Obama seems quite unlikely to adopt either of those policy prescriptions, unfortunately. He's promising to freeze non-defense discretionary spending, but that's a mere drop in the almost $4 trillion federal budget bucket. He will probably suggest some tax credits, but those are ineffective at stimulating growth since they aren't permanent and they don't reward increased work and risk-taking. He may offer some tax cuts to small businesses, but how effective they will be remains to be seen. He'll want to spend more money on jobs programs, but that reflects a woeful ignorance of how jobs are created—real jobs are created by the private sector, not by government bureaucrats or spending programs. And with the budget deficit likely to exceed 10% of GDP for the foreseeable future, government borrowing demands can gobble up enormous amounts of credit that could otherwise be used by the private sector for more productive causes.

As for monetary policy, the Fed is sailing in uncharted waters that have the potential to be quite inflationary, but only a handful of folks in Washington are calling for Bernanke to step on the monetary brakes, and not a single Democrat is included in that count.

And thus the year starts with very high stakes at play. I'm counting on the sea-change in the electorate, to judge by the recent Massachusetts vote, to block counterproductive Keynesian spending programs. I'm counting on the economy's inherent dynamism to overcome the adverse headwinds of unproductive government spending programs, as it has done all year long. And I'm counting on all the green shoots and V-signs that I have seen over the past year—signs that the economic fundamentals have improved dramatically and with no help from monetary or fiscal stimulus—to keep economic growth alive, even though unemployment is unlikely to come down meaningfully anytime soon.

One big tailwind I'm counting on is that I think the market is still so worried about a whole host of concerns—another wave of real estate defaults and foreclosures, a dearth of new jobs, another wave of housing defaults, Chinese monetary tightening, a lack of bank lending, huge economic slack (which supposedly threatens deflation), the Fed's inability to reverse its quantitative easing in time—or an unexpected Fed tightening, trillion dollar deficits, the very weak dollar, Obama's increasingly evident inexperience—that any morsel of good news will be a big plus. And despite the constant drumbeat of concerns, we've had a steady diet of good news for many months.

So while there is no shortage of things to worry about, I do see a very significant shift in the political winds. If Obama is going to make any changes to his strategy, they will likely be of the type that is less anti-business and less anti-growth. Even if he doesn't have Bill Clinton's ability to triangulate, Obama today has much less freedom to maneuver on the left. He may feel miserable, but all is not lost from the market's perspective.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

Here's how much rates are expected to rise

A question from a reader made me think that this chart might be of interest. It comes from Bloomberg, and is designed to show the market's implied forecast of interest rates at different points in time. The current Treasury yield curve is the bottom red line, and as you move up the chart you have the expected curve 1, 2, and 5 years from now.

The mathematics of the yield curve dictate that if you want to make money by shorting a bond today, then you will win your bet only if the yield on that bond exceeds the expected yield. Thus, you can make money shorting the 10-year for the next 5 years only if the 10-year yields more than 4.9% at the end of that period.

It's also interesting to see just how much the market expects the Fed to tighten over the next 5 years: by some 450 bps. This is like the "line" in betting: you win the bet on rising interest rates only if they exceed the line.

Housing price bottom still holding

The Case Shiller home price index in November rose for the sixth month in a row. Even after adjusting for inflation, home prices are up. And given the nature of the index, which operates with a significant lag, the message here is that home prices in 20 major markets hit bottom sometime around last March or April, after declining 36% in real terms from the high of early 2006. The housing price bubble popped, but it is no longer deflating. Prices have come back into line with incomes (actually, housing affordability is near an all-time recorded high, according to the National Association of Realtors) and interest rates have fallen to historically low levels. This is how markets adjust to changing circumstances. The $500,000 home that turned into a deadweight albatross for the guy who bought it in 2006 is now a $320,000 dream house for the guy who buys it today.

Obama's proposed spending freeze: way too little, way too late

Is it that Obama is foolish, or is it his advisors that are stupid? You have to wonder why the White House has decided to make a big deal about freezing spending on 17% of the federal budget. This can only invite scrutiny such as this chart: spending is off the charts, and freezing a tiny portion of it is not going to make any difference. We're talking about a budget that will soon reach $4 trillion, and Obama thinks that spending $20 billion less over the next year is a big deal?

Monday, January 25, 2010

Reading the monetary tea leaves

Supply-siders like me believe that the market is a great source of information about the forces acting on the economy. This post focuses on what market prices are saying about the future of inflation.

(Just to be clear, as a supply-sider I think inflation should be as close to zero and as stable as possible. One way to do that, I believe, would be to return the U.S. to a gold standard or something similar that ties the dollar's value to an objective, physical standard. Central banking should not rest on the discretion or the judgment of a small group of (fallible) Wise Old Men, it should be about keeping the purchasing power of the dollar stable and predictable no matter what. The central banker of my dreams would be a person who firmly believed that the measure of his or her success would be directly proportional to how low and stable inflation proved to be, and inversely proportional to how much he or she had to work.)

Inflation happens when there is too much money relative to the demand for it, but how do you know when there is too much money? As I've discussed before, there's no good measure of money supply, but there are good proxies for money demand. But without knowing money supply, how can you tell if it is exceeding money demand? The answer lies in the market-driven prices of the dollar, gold, commodities, T-bonds (i.e., the yield curve), breakeven spreads on TIPS, and credit spreads. What follows is a quick survey of what I think each of these prices is telling us about monetary policy and the outlook for inflation. If I were to replace Bernanke, these are the things that I would pay the most attention to.

Against a broad basket of many currencies, and adjusted for inflation differentials and trade weighted, the value (i.e., the price) of the dollar is only slightly above its all-time low level. So today the dollar confirms that the Fed is pursuing an accommodative monetary policy, supplying more dollars to the world than the world wants. Moreover, Fed governors say that this is exactly what they are trying to do. They want at all costs to avoid deflation and depression, which can be precipitated by a shortage of dollars relative to demand. The Fed is willing to err on the side of more inflation in order to avoid what they perceive to be the much greater risk of deflation and depression. The world's investors have by and large figured out that the Fed has a bias to see the dollar weaker, and they are less willing to hold dollars as a result.

Gold prices are close to an all-time high in nominal terms, but in today's dollars they are still shy of the $1800/oz high that occurred in early 1980 (note that the chart only plots year-end values). Gold prices are thus agreeing with the message of the dollar: there is a surplus of dollars in the world (but not nearly as much as there was in the late 1970s, thank goodness), and that makes investors nervous about the dollar's future purchasing power, which in turn leads to an increased demand for gold. Gold has the unique quality of being both monetary and physical, and its price has, over very long periods, tended to rise by the rate of inflation. If I had a chart of the real price of gold over various centuries, I think it would show that gold's price, in today's dollars, averages somewhere in the range of $400-500/oz. Thus, gold is correctly viewed to be the classic inflation hedge, with demand for gold rising and falling with inflation fears and fundamentals.

Commodity prices are still somewhat below their 2008 highs, but virtually all commodity prices have risen significantly in the past year or so against the dollar, and are well above the levels that prevailed in the 1980-2003 period when central banks around the world were tight and inflation was generally low and relatively stable. Commodity prices started rising about one year after gold prices started rising in 2001, confirming the message of the dollar, gold and the statements of most central bankers that monetary policy has been in an accommodative mode for most of the past 9 years. It's interesting to note that this same commodity price series is roughly unchanged over the past 30 years in terms of the Swiss franc, while it is up about 50% in dollar terms. It's not a coincidence that the U.S. has experienced about 50% more inflation than Switzerland in the past 30 years, because currency depreciation inevitably leads to inflation.

As the top chart just above shows, the slope of the yield curve is almost always inversely proportional to the degree of Fed tightness (measured by adjusting the target Fed funds rate for inflation). When the Fed is tight, real short rates are high and the yield curve is flat or inversely (negatively) sloped. Today the yield curve is steeper than ever before, confirming that the Fed is extremely easy. At the very least this is a necessary if not sufficient condition for rising inflation.

The two charts together show that the Fed almost always tightens policy as inflation rises, and eases policy as inflation falls. One major exception to this rule occurred in the 1995-2000 period, when the Fed tightened and the yield curve turned negative, yet inflation was flat or falling. I think this unwarranted tightening provides a very good explanation for why the U.S. economy was on the verge of deflation in the 2001-2003 period. Furthermore, the period of extreme Fed ease which followed was a key factor in driving commodity prices higher, the dollar lower, housing prices higher, and inflation higher over the 2003-2008 period.

The chart above shows the 5-year, 5-year forward breakeven spread on TIPS. That's the market's expectation of what the 5-year outlook for inflation will be five years from now. Not only have inflation expectations increased sharply in the past year, but the expected level of inflation (2.8%) now exceeds the average level of CPI inflation (2.6%) over the past 10 years.

Unfortunately there is a lack of good data on credit spreads going back in time, so I am forced to use this last chart to argue from a more intuitive basis. Credit spreads are the market's way of expressing default risk; the higher the spread, the greater the risk of default. Default risk is driven by a number of factors, but two important ones are the strength of the economy and the level of inflation. A strong economy typically leads to low credit spreads, since a healthy economy is good for corporate cash flows. A weak economy, in contrast, typically leads to rising spreads, since cash flows become uncertain and business bankruptcies almost always rise during and in the immediate aftermath of a recession.

Changing levels of inflation can also lead to changes in credit spreads. When inflation is high and rising, debtors are usually quite happy because their real cost of borrowing is low and they are able to raise their prices by more than they anticipated, which in turn means that their cash flows are stronger than expected. Rising inflation favors debtors to the disadvantage of creditors, so whne inflation rises investors are more willing to purchase corporate debt, and highly indebted issuers (i.e., junk bonds) benefit disproportionately. Thus, higher inflation typically contributes to lower credit spreads. Just the opposite is true when inflation is very low and/or when monetary policy is very tight, since it's difficult or impossible to raise prices, and the real cost of borrowing is very high. The best example of this was late 2008/early 2009, when inflation was sharply negative and many firms were forced to lower their prices; cash flows deteriorated and credit spreads shot up to unprecedented levels. Today, credit spreads are still high from an historical perspective, but the fact that they have plunged over the past year is one more piece of evidence that monetary policy is easy and inflation is returning.

Summary: All of these market-based indicators of inflation fundamentals are pointing in the same direction: higher. Meanwhile, traditional indicators of inflation that the Fed focuses on, such as the degree of economic slack and the unemployment rate, are pointing to very low or even negative inflation. Who's right? No one that I know has yet come up with a foolproof method or theory for predicting inflation, but I think it is reasonable to predict that inflation will be higher than the market expects (current expectations being for inflation to average 2-2.5% over the next 5-10 years).

(Just to be clear, as a supply-sider I think inflation should be as close to zero and as stable as possible. One way to do that, I believe, would be to return the U.S. to a gold standard or something similar that ties the dollar's value to an objective, physical standard. Central banking should not rest on the discretion or the judgment of a small group of (fallible) Wise Old Men, it should be about keeping the purchasing power of the dollar stable and predictable no matter what. The central banker of my dreams would be a person who firmly believed that the measure of his or her success would be directly proportional to how low and stable inflation proved to be, and inversely proportional to how much he or she had to work.)

Inflation happens when there is too much money relative to the demand for it, but how do you know when there is too much money? As I've discussed before, there's no good measure of money supply, but there are good proxies for money demand. But without knowing money supply, how can you tell if it is exceeding money demand? The answer lies in the market-driven prices of the dollar, gold, commodities, T-bonds (i.e., the yield curve), breakeven spreads on TIPS, and credit spreads. What follows is a quick survey of what I think each of these prices is telling us about monetary policy and the outlook for inflation. If I were to replace Bernanke, these are the things that I would pay the most attention to.

Gold prices are close to an all-time high in nominal terms, but in today's dollars they are still shy of the $1800/oz high that occurred in early 1980 (note that the chart only plots year-end values). Gold prices are thus agreeing with the message of the dollar: there is a surplus of dollars in the world (but not nearly as much as there was in the late 1970s, thank goodness), and that makes investors nervous about the dollar's future purchasing power, which in turn leads to an increased demand for gold. Gold has the unique quality of being both monetary and physical, and its price has, over very long periods, tended to rise by the rate of inflation. If I had a chart of the real price of gold over various centuries, I think it would show that gold's price, in today's dollars, averages somewhere in the range of $400-500/oz. Thus, gold is correctly viewed to be the classic inflation hedge, with demand for gold rising and falling with inflation fears and fundamentals.

The two charts together show that the Fed almost always tightens policy as inflation rises, and eases policy as inflation falls. One major exception to this rule occurred in the 1995-2000 period, when the Fed tightened and the yield curve turned negative, yet inflation was flat or falling. I think this unwarranted tightening provides a very good explanation for why the U.S. economy was on the verge of deflation in the 2001-2003 period. Furthermore, the period of extreme Fed ease which followed was a key factor in driving commodity prices higher, the dollar lower, housing prices higher, and inflation higher over the 2003-2008 period.

The chart above shows the 5-year, 5-year forward breakeven spread on TIPS. That's the market's expectation of what the 5-year outlook for inflation will be five years from now. Not only have inflation expectations increased sharply in the past year, but the expected level of inflation (2.8%) now exceeds the average level of CPI inflation (2.6%) over the past 10 years.

Unfortunately there is a lack of good data on credit spreads going back in time, so I am forced to use this last chart to argue from a more intuitive basis. Credit spreads are the market's way of expressing default risk; the higher the spread, the greater the risk of default. Default risk is driven by a number of factors, but two important ones are the strength of the economy and the level of inflation. A strong economy typically leads to low credit spreads, since a healthy economy is good for corporate cash flows. A weak economy, in contrast, typically leads to rising spreads, since cash flows become uncertain and business bankruptcies almost always rise during and in the immediate aftermath of a recession.

Changing levels of inflation can also lead to changes in credit spreads. When inflation is high and rising, debtors are usually quite happy because their real cost of borrowing is low and they are able to raise their prices by more than they anticipated, which in turn means that their cash flows are stronger than expected. Rising inflation favors debtors to the disadvantage of creditors, so whne inflation rises investors are more willing to purchase corporate debt, and highly indebted issuers (i.e., junk bonds) benefit disproportionately. Thus, higher inflation typically contributes to lower credit spreads. Just the opposite is true when inflation is very low and/or when monetary policy is very tight, since it's difficult or impossible to raise prices, and the real cost of borrowing is very high. The best example of this was late 2008/early 2009, when inflation was sharply negative and many firms were forced to lower their prices; cash flows deteriorated and credit spreads shot up to unprecedented levels. Today, credit spreads are still high from an historical perspective, but the fact that they have plunged over the past year is one more piece of evidence that monetary policy is easy and inflation is returning.

Summary: All of these market-based indicators of inflation fundamentals are pointing in the same direction: higher. Meanwhile, traditional indicators of inflation that the Fed focuses on, such as the degree of economic slack and the unemployment rate, are pointing to very low or even negative inflation. Who's right? No one that I know has yet come up with a foolproof method or theory for predicting inflation, but I think it is reasonable to predict that inflation will be higher than the market expects (current expectations being for inflation to average 2-2.5% over the next 5-10 years).

Housing update

Much is being made of the unexpectedly large December decline in existing homes sales. But a glance at the top chart should make it clear that the big aberration was the November increase, which was driven by expectations that the homebuyers tax credit was expiring. Even if you assume that sales decline again in January (although the tax credit has been extended), they would still likely be much higher than they were in Jan. '09. As the second chart shows, there has been clear and impressive improvement in the fundamentals of the housing market, with the supply of unsold homes having dropped significantly over the course of the past year.

Real estate bottoming?

This chart compares the Case Shiller index of residential home prices to Moody's Commercial Property Price Index. Both are elaborate indices, and the Moody's series uses methodology developed at MIT. Both use data on repeat sales for a relatively large sampling of properties.

Note that the rise in commercial real estate lagged the rise in residential. CRE rose a bit less than residential during the heydays, but it has declined by much more. The commercial real estate market has been crushed. Both indices now are showing signs of having bottomed. It's too early to call a bottom in CRE, but taken in the context of the sheer magnitude of the decline (-43% from the Oct. '07 high), the November uptick in the Moody's index does provide some tentative support for a bottoming hypothesis. A bottom in real estate is not an unrealistic expectation, in any event, given the many signs of improving economic fundamentals, rising commodity prices, very low interest rates, and the significant rise in the prices of commercial real estate-backed securities.

Mortgage rate update

As the top chart shows, 30-year fixed rate jumbo mortgage rates are going for a post-crisis low, a rate not seen since 2005. With a few scattered exceptions, the rate you get today is about as low as it has ever been in history. Conforming rates are still very close to all-time lows.

As the second chart shows, the fundamentals driving these rates (i.e., 10-year Treasury yields and the spread between MBS and Treasury yields that investors demand in order to compensate them for the prepayment risk of mortgage-backed securities) suggest that we are unlikely to see rates go lower than they are now. Treasury yields are quite low from an historical perspective, and spreads are about as tight as they have ever been.

One other interesting fact that shows up in the first chart is that the difference between jumbo and conforming mortgage rates is still quite large. That means that even if conforming rates move higher, it will likely take awhile before jumbo rates move higher; the spread between them could compress by another 25-50 bps. However, I should also point out that the declining spread between jumbo and conforming loan rates is a very good sign that private capital is returning to the mortgage market. The Fed is only buying conforming mortgages, not jumbos, so jumbos have been outperforming conforming MBS, which in turn suggests that private capital has been actively seeking out the higher yields on jumbos. That is also an indication that when the Fed stops buying MBS at the end of March, there is no reason to expect mortgage rates to move significantly higher.

I continue to believe that prospective homebuyers would be well-served to choose a 30-year fixed rate mortgage instead of an adjustable rate. Fixed rates are very low from an historical perspective, while the short-term rates that drive ARMs are very likely to rise significantly in coming years. With the fixed rate you get the certainty of locking in an historically low rate, but with adjustable rates you are exposed to considerable uncertainty down the road, because no one knows today how high short-term rates will be in the future.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Industrial production update

Industrial production continues to rise all over the globe. Levels are still depressed, of course, but on the margin we see distinct improvement across the board.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Thoughts on Obama post-Massachusetts

Here is an update of my charts of the polling results from the folks at Rasmussen. Obama's popularity continues to trend down, and the stock market this past week cast a big negative vote on where he is likely headed. Apparently he has decided that the Democrats lost Massachusetts because the electorate is still mad at Bush. His ego is so big that he can't allow himself to even think that it was a vote against him and his cherished healthcare reform. Now he wants to distract everyone's attention from the fiasco by pulling a standard populist ploy and beating up on the banks. When will this guy ever learn? As Charles Krauthammer notes, "You would think lefties could discern a proletarian vanguard when they see one."

If I could paraphrase the late Jude Wanniski, the job of a politician is not to lead the people, it is to figure out where the people want to go and then help them get there.

Obama's headed in the wrong direction, but that doesn't mean all is lost. On the contrary. The electorate is jumping up and down and waving its arms, and not all politicians are deaf or blind to the message. There's a new politics afoot, and what is happening on the political margin is not Democrats vs. Republicans. It's now about more government programs vs. fewer; government bureaucrats making decisions vs. individuals making decisions about what's in their best interest; more spending vs. less; free markets vs. mandates; more income redistribution vs. less; higher taxes vs. lower taxes; and more individual freedom vs. less. It's no longer about abortion or same-sex marriage or gay rights or welfare. Our fiscal situation demands that we put aside the social issues for now and focus on the role of government in our lives.

Obama needs to refocus and perhaps triangulate as Bill Clinton did following the Democrats' trouncing in the 1994 elections. If he doesn't, his party and the electorate will rise up against him, and the Massachusetts massacre will be repeated. Sooner or later he will need new advisors, and he will need to focus on the economy and drop healthcare. More spending programs and populist attacks on banks and big business won't work anymore. He won't be able to push his former agenda any further—he's got to find a new one, and it has to be more palatable to those who want less government and more individual freedom. At the worst we will end up with gridlock, and if we're lucky we may see Obama & Co. moving in Clintonesque fashion to the center, where things can get done. Whatever the case, it's a huge improvement considering where we've come from.

Optimism is still the order of the day.

To close, here are some timely quotes from Ronald Reagan that are worth repeating:

"Socialism only works in two places: Heaven where they don't need it and hell where they already have it."

"Here's my strategy on the Cold War: We win, they lose."

'The most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the government and I'm here to help."

'The trouble with our liberal friends is not that they're ignorant; it's just that they know so much that isn't so."

"Of the four wars in my lifetime, none came about because the U.S. was too strong."

"Government is like a baby: An alimentary canal with a big appetite at one end and no sense of responsibility at the other."

'The nearest thing to eternal life we will ever see on this earth is a government program."

"It has been said that politics is the second oldest profession. I have learned that it bears a striking resemblance to the first."

"Government's view of the economy could be summed up in a few short phrases: If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it."

"Politics is not a bad profession. If you succeed, there are many rewards; if you disgrace yourself, you can always write a book."

HT: Don T.

Friday, January 22, 2010

Implied volatility update

This chart shows the implied volatility of equity and T-bond options. Implied vol can be thought of as a proxy for the level of fear, uncertainty and doubt that inhabits the market. Implied vol has fallen sharply over the past year as the market's many and deep-seated fears were resolved: the economy hasn't fallen down a black hole; this isn't another Depression; there is no deflation; Obama is not going convert the country to socialism; we aren't going to have a global trade war; political balance (gridlock is a good thing) is returning; there are many signs of recovery.

There are still lingering concerns, of course. How fast will the recovery be? Are we being set up for another slump? How will the Fed reverse its quantitative easing? Will inflation go up a little, a lot, or not at all? Will trillion dollar deficits go on forever? Will businesses find the courage and the capital to create new jobs?

Despite these concerns, I think there has been enough progress on many fronts that the future looks appealing, if not bright. Our financial markets have largely healed, and our political system is working to provide checks and balances. The economy has undergone a tremendous adjustment process, with the result that we now have a relatively solid base upon which to build a recovery. The housing market has also undergone radical adjustment, with an unprecedented decline in prices and residential construction, but this also is a necessary step and a base upon which to mount a recovery. The global economy is recovering as well.

I think it still pays to be an optimist.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

China looks good (2)

Here's an update to my post last month, showing China's GDP growth returning to double digits as expected. This is very impressive, and surely qualifies as one of the most impressive V-shaped recoveries to date. Yet the market is concerned that measures imposed by the government to curb bank lending, announced today, coupled with a rise in the required reserve ratio for banks last week, will threaten China's economic future. I see these measures instead as moves in the right direction.

Because China's currency is linked to the dollar, and the dollar is historically very weak and the Fed is promising zero interest rates for a long time to come, it is in China's best interests to resist the inflationary pressures that flow from a weak currency. Tighter monetary policy is one way to do this, but ultimately China will probably have to revalue the yuan against the dollar—unless the dollar rises appreciably in the interim. But neither a revaluation of the yuan nor a tightening of monetary policy should pose a threat to China's growth, because they would amount to appropriate measures to limit inflationary pressures. It's never a bad thing to do the right thing.

It's useful to recall the unwritten law of central banking. A central bank can successfully implement monetary policy by choosing one of three policy tools: controlling the exchange rate, controlling the money supply, or controlling an interest rate. Often central banks that choose the first option become tempted to use one or two of the other tools at the same time. We saw this in the years leading up to the S.E. Asian currency crises of 1997, when central banks raised interest rates to cool off their economies (at the IMF's suggestion, I might add) while also keeping their currencies pegged to the dollar. This can work for short periods, but it inevitably results in undesirable or unforseen consequences. The problem is that it is just about impossible for any human to use two policy tools to hit one policy target; the complexity is just too great. If policymakers can stick to just one tool, then markets and the economy can adjust given time.

Think about it: if China says the yuan will be fixed to the dollar, but then it raises its interest rates above dollar interest rates, this has the effect of attracting capital that would otherwise go to the U.S. Increased capital flows have to be purchased by the central bank in order to keep the exchange rate stable, but this increases the money supply and that, in turn, can put downward pressure on interest rates and/or result in an "overheated" economy. In short, the combination of these policies can end up in undesirable cross-currents.

So China is probably making a mistake by tightening monetary policy instead of just revaluing the yuan. But it could take a long time for this mistake to generate serious imbalances in the economy. In the meantime, investors know that China has a virtual mountain of reserves with which to back up its currency. That means the Chinese yuan is NOT going to lose its value; it can only remain steady versus the dollar or rise. So on the margin, the central bank's tinkering with monetary policy only increases the appeal of investing in China, since it means higher interest rates (which is equivalent to curbing bank lending) and/or an increased likelihood of further yuan appreciation against the dollar. And the more money that is attracted to China, the more resources it will have at its disposal to continue growing. For now, it's a virtuous circle.

Full disclosure: I am long CHN at the time of this writing.

Fama on the financial crisis and "credit bubbles"

Eugene Fama, father of the efficient markets hypothesis, makes some good points in this interview in The New Yorker Magazine. Questioned as to whether the credit market could be considered efficient if "people were getting loans, especially home loans, which they shouldn't have been getting," he replied:

In other words, it wasn't inefficient markets that led to the financial crisis, it was government intervention in markets that caused the crisis.

Questioned as to whether the credit market bubble that inflated and then burst could be considered an inefficiency that led to the 2008 financial crisis, he replied:

Credit can be created by one person lending money to another, but that does not result in any increase in money outstanding, nor does it create any new demand. (New money is created only when banks extend credit via the fractional reserve system; when they do so, then the money supply expands.) If I take money out of my pocket and lend it to John, I have created credit, and the money I don't spend he now has to spend. Perhaps he turns around and lends it to George; that adds further to the amount of credit outstanding, but again it doesn't increase the amount of money in the system, nor does it create any new demand—it only shifts demand from one party to another.

From this it follows that, as Fama notes, if you argue that there was "too much credit" in the system, then you are also saying there was perhaps too much saving. Yet many of those who worry about too much credit also argue that another big problem in the U.S. economy in the past several decades has been profligate consumption and a very low savings rate. Someone is very wrong here, and it is the misunderstanding of how credit works that explains it.

Those who point to a credit bubble as the culprit in this crisis fail to understand that the growth in credit is not the same as an inflationary expansion in the amount of money. Credit can grow very rapidly or very slowly without creating any necessary implications for inflation. In a low and stable inflation world, it is entirely possible for credit to experience rapid growth. Indeed, rapid growth in credit is most likely to occur when conditions are stable and confidence is high.

When inflation is high and volatile, lending money becomes a very risky business and credit dries up. I know, because when I lived in Argentina during the triple-digit inflation of the late 1970s, I discovered that the average maturity of loans was measured in months, not years. To buy a house, for example, the best terms I could find were 30-60-90: one third of the price in 30 days, the next third in 60 days, and the final third in 90 days. When inflation and risk are high, no one wants to lend. Lending flourishes, in contrast, during periods of stability and confidence.

If you're looking for a guilty party to blame for the financial crisis, blame the federal government for mandating inefficiencies in the way FNMA and FHLMC operated, and blame the Fed for keeping interest rates too low for too long. The Fed's easy money policy caused the demand for money to decline. As a result of easy money, people came to want less money and more things, and that's one reason why housing, commodity and gold prices rose so strongly in the years leading up to the crisis. The price of the dollar fell and the price of things rose, and the rise in housing prices greatly exceeded the rise in incomes. This was the "bubble" that eventually popped: prices that got out of line with the ability to pay.

Moral: don't confuse "credit" with inflationary monetary policy. They are two very different things.

That was government policy; that was not a failure of the market. The government decided that it wanted to expand home ownership. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were instructed to buy lower grade mortgages.

In other words, it wasn't inefficient markets that led to the financial crisis, it was government intervention in markets that caused the crisis.

Questioned as to whether the credit market bubble that inflated and then burst could be considered an inefficiency that led to the 2008 financial crisis, he replied:

I don’t even know what that means. People who get credit have to get it from somewhere. Does a credit bubble mean that people saved too much during that period?I like this response because I have argued along the same lines before. To say that a credit bubble (commonly viewed as a significant rise in the ratio of household debt to GDP) caused our problems is to ignore some important facts. In the absence of any evidence that the money supply grew by an unusual amount relative to the size of the economy (on average, M2 grew only 1% per year faster than GDP from 1997-2008), then the large increase in credit outstanding that we observed over those same years was the result of voluntary private sector activity.

Credit can be created by one person lending money to another, but that does not result in any increase in money outstanding, nor does it create any new demand. (New money is created only when banks extend credit via the fractional reserve system; when they do so, then the money supply expands.) If I take money out of my pocket and lend it to John, I have created credit, and the money I don't spend he now has to spend. Perhaps he turns around and lends it to George; that adds further to the amount of credit outstanding, but again it doesn't increase the amount of money in the system, nor does it create any new demand—it only shifts demand from one party to another.

From this it follows that, as Fama notes, if you argue that there was "too much credit" in the system, then you are also saying there was perhaps too much saving. Yet many of those who worry about too much credit also argue that another big problem in the U.S. economy in the past several decades has been profligate consumption and a very low savings rate. Someone is very wrong here, and it is the misunderstanding of how credit works that explains it.

Those who point to a credit bubble as the culprit in this crisis fail to understand that the growth in credit is not the same as an inflationary expansion in the amount of money. Credit can grow very rapidly or very slowly without creating any necessary implications for inflation. In a low and stable inflation world, it is entirely possible for credit to experience rapid growth. Indeed, rapid growth in credit is most likely to occur when conditions are stable and confidence is high.

When inflation is high and volatile, lending money becomes a very risky business and credit dries up. I know, because when I lived in Argentina during the triple-digit inflation of the late 1970s, I discovered that the average maturity of loans was measured in months, not years. To buy a house, for example, the best terms I could find were 30-60-90: one third of the price in 30 days, the next third in 60 days, and the final third in 90 days. When inflation and risk are high, no one wants to lend. Lending flourishes, in contrast, during periods of stability and confidence.

If you're looking for a guilty party to blame for the financial crisis, blame the federal government for mandating inefficiencies in the way FNMA and FHLMC operated, and blame the Fed for keeping interest rates too low for too long. The Fed's easy money policy caused the demand for money to decline. As a result of easy money, people came to want less money and more things, and that's one reason why housing, commodity and gold prices rose so strongly in the years leading up to the crisis. The price of the dollar fell and the price of things rose, and the rise in housing prices greatly exceeded the rise in incomes. This was the "bubble" that eventually popped: prices that got out of line with the ability to pay.

Moral: don't confuse "credit" with inflationary monetary policy. They are two very different things.

Yet again, rising uncertainty drives a temporary selloff

I'm going to blame Obama's proposed restrictions on the activities of banks for today's selloff. It seems that he is unwilling to accept the message of the voters in the Massachusetts special election. In his ignorance he is joined by the hopelessly biased New York Times, whose editorial stated that "To our minds, it is not remotely a verdict on Mr. Obama’s presidency, nor does it amount to a national referendum on health care reform..."

Both instead are blaming the economy, which in turn they say is the legacy of Bush and those unfettered, greedy capitalist banks. So he is going to go after the banks and try to divert attention from his own shortcomings. Populist appeals of this sort, however, are not going to restore his popularity nor will they endear the public to his big-government message. Tuesday's vote made that clear.

When you see Obama and the Democratic establishment turn a deaf ear to the powerful message that came out of yesterday's election, then you just have to keep betting against them. They won't be able to hobble the banks, just as they weren't able to saddle us with a disastrous healthcare reform.

Still, as the chart above shows, these maneuvers create great uncertainty, and thus the VIX index shot up today as stocks fell. What I think we'll see sooner or later is that the economy is capable, once again, of improving despite all the headwinds originating in the White House. I remain optimistic and so I see selloffs such as these as buying opportunities.

Weekly claims update

Weekly unemployment claims were higher than expected, but blips like this happen all the time. The 4-week moving average hardly budged, in fact. I see no signs that would suggest the economy is about to turn down. We're still on track for a moderate recovery.

Leading indicators: another V-sign

As I said before when I posted this chart back in September, I don't pay much attention to the "leading economic indicators." They don't really lead, and they can sometimes be "mis-leading." But they can be very good coincident indicators, and they appear to have done a good job of calling the end of the recession back in mid-2009. They've turned up quite sharply over the second half of 2009, and are exhibiting the classic signs of the beginning of a new business cycle. I don't see any signs that would suggest this recovery is at risk anytime soon.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Export activity continues to rebound

Export activity continues to rise, and that is good news for just about everyone. I've been showing this chart since early last year, pointing out that data on container shipments from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach were likely leading indicators of overall U.S. export activity. Outbound container shipments from Los Angeles surged 40% last year (the green line in the chart), marking a significant V-shaped recovery in the wake of the collapse of global trade in late 2008. We've already seen U.S. goods exports rise 18% from the lows of April '09, so we can most likely expect to see continued strong gains in the months to come (because shipping data is more up to date than the export data that is reflected in the GDP stats), and this will in turn be an important source of growth for the economy.

The strong rebound in global trade that we have seen this past year is a very good reason to be bullish about the future.

Housing starts vs permits

Recovery skeptics are making a big deal of the fact that housing starts fell 4% in December (seasonally adjusted). Recovery fans are excited about the 10.9% rise in building permits, which would point to higher starts next month. I look at both these series and see signs that activity has probably stabilized and may be rising. If things have only stabilized, this would be a very good sign for the residential construction sector, because it would signal that the supply of and demand for housing was coming into balance. That's an important ingredient in the stabilization of prices. And stable home prices (and they may actually be rising on average) would do wonders for the value of many hundreds of billions of subprime mortgage-backed securities that are priced, I'm told, to the assumption that nationwide housing prices are going to fall another 15%. If home prices don't fall 15%, then the prices of those securities must perforce rise significantly; that in turn would generate huge gains for the portfolios of institutional investors and financial institutions that are holding them.

We don't really need to see housing turn up to be optimistic about the future; we only need to see signs that housing has finally stabilized.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Another sign of a housing bottom

This Bloomberg index of the stocks of major home builders is up 133% from its Mar. '09 low. That's pretty impressive, especially since housing starts are up only 10% over the same period, and the NAHB index of builders looks pretty flat. I think this is a clear instance of the market "looking across the valley" of current despair. Residential construction has fallen to all-time lows relative to the market, and is way below the levels needed to keep up with a growing population. The industry has contracted for four straight years, and this can't go on forever. We've most likely seen the bottom in housing. Of course, the recovery may take awhile and it may be tepid, but the bad news is a thing of the past. Now, it's only a question of how fast and how strong the recovery is.

The 4% barrier

10-year Treasury yields are a great way to measure the market's degree of optimism. When they dropped to almost 2% at the end of 2008, they were telling us that the market was extraordinarily pessimistic, in fact terrified that we faced years of depression and deflation. At 3.7% today, the market now thinks that while depression is unlikely, the economy is still going to be plagued by years of weak growth. If 10-year T-bond yields rise above 4%, which I think is likely, that will be a good sign that the market is coming to accept that we have at least a decent recovery on our hands. At 5%, the market would be telling us that the outlook for the economy was becoming rather robust and/or inflation was clearly moving higher than the Fed's 1-2% target zone.

Higher interest rates are definitely not something to fear, at least for now. They would have to go much, much higher before they became a threat to growth, and by that time the economy would be a lot stronger than it is today.

"Mass" tipping point?

(Apologies for not posting for several days. I was enjoying a 4-day ski vacation in Lake Tahoe.)

If Scott Brown wins his Massachusetts Senate seat in today's special election, I think this will mark a major tipping point in U.S. politics. (The first tipping point arguably came last year in March and April, when Obama's agenda first started running into difficulties. I remarked at the time that I thought he was far too liberal for the tastes of America's voters, that he would not find it possible to push through his agenda, and that this was a reason to be bullish on stocks, especially since they were so cheap.) Now we see the centerpiece of the liberal agenda running into a brick wall of resistance. As the WSJ editorial today points out, "The real message of Massachusetts is that Democrats have committed the classic political mistake of ideological overreach."

One of the drivers of the equity rally this past year has been the inability of the Obama administration to implement all of its far-left agenda. Going forward, one of the drivers of continued equity market gains could be the beginnings of an actual rightward shift in policies, not just a failure to move to the left. At the very least, Congress may now start operating as a divided house, and Divided Government is a thing devoutly to be wished at this point. A little less government would be a very good thing. We've come a long way in the past year, thank goodness.

UPDATE: With Brown's decisive win, this changes the political landscape to an enormous extent. I don't see how healthcare reform can pass in anything like its current form. Furthermore, I don't see how we could see any significant, hard-left measures pass between now and the November elections, when Democrats are sure to lose their commanding majority in Congress. We are now in a new era of Divided Government, and that is a Very Good Thing from the market's perspective. Obama, the One-Year Wonder, is now faced with the need to salvage his presidency. Will he choose the high road, and call for Congress to scrap the current healthcare proposal and start again from scratch, with true bi-partisan input? Or will he choose the low (Chicago) road, and go for broke? These are exciting times.

If Scott Brown wins his Massachusetts Senate seat in today's special election, I think this will mark a major tipping point in U.S. politics. (The first tipping point arguably came last year in March and April, when Obama's agenda first started running into difficulties. I remarked at the time that I thought he was far too liberal for the tastes of America's voters, that he would not find it possible to push through his agenda, and that this was a reason to be bullish on stocks, especially since they were so cheap.) Now we see the centerpiece of the liberal agenda running into a brick wall of resistance. As the WSJ editorial today points out, "The real message of Massachusetts is that Democrats have committed the classic political mistake of ideological overreach."

One of the drivers of the equity rally this past year has been the inability of the Obama administration to implement all of its far-left agenda. Going forward, one of the drivers of continued equity market gains could be the beginnings of an actual rightward shift in policies, not just a failure to move to the left. At the very least, Congress may now start operating as a divided house, and Divided Government is a thing devoutly to be wished at this point. A little less government would be a very good thing. We've come a long way in the past year, thank goodness.

UPDATE: With Brown's decisive win, this changes the political landscape to an enormous extent. I don't see how healthcare reform can pass in anything like its current form. Furthermore, I don't see how we could see any significant, hard-left measures pass between now and the November elections, when Democrats are sure to lose their commanding majority in Congress. We are now in a new era of Divided Government, and that is a Very Good Thing from the market's perspective. Obama, the One-Year Wonder, is now faced with the need to salvage his presidency. Will he choose the high road, and call for Congress to scrap the current healthcare proposal and start again from scratch, with true bi-partisan input? Or will he choose the low (Chicago) road, and go for broke? These are exciting times.

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Mortgage rate update

Mortgage rates continue to be very close to their all-time lows. Low mortgage rates plus lower home prices plus higher real incomes add up to make housing much more affordable—according to the National Assoc. of Realtors' index of affordability shown here—than at any time in the past 20 years (with the exception of early last year, when mortgage rates were briefly lower than they are today).

Claims update

Weekly unemployment claims are still pretty high from an historical perspective, but I note that they were this high or higher more than a year after the last two recessions. The "healing" of the job market (defined as the reduction in the number of people being laid off) has proceeded at a much faster pace this time around. That's most likely due to the severity of this recession, of course, but it's a positive spin that gets easily overlooked.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

The inconvenient financial realities of healthcare reform

As Cato's Michael Cannon details in a policy analysis published today, the healthcare reform bills currently under consideration in Congress contain provisions that would "penalize work and reward Americans who refuse to purchased health insurance." Not only do they promise to be a fiscal disaster, but they will also do significant harm to the incentives of low- and middle-income single workers and families. A must read for all who want to understand what these bills really entail. Excerpts:

... mandates and subsidies would impose effective marginal tax rates on low-wage workers that would average between 53 and 74 percent— and even reach as high as 82 percent—over broad ranges of earned income. By comparison, the wealthiest Americans would face tax rates no higher than 47.9 percent.

Over smaller ranges of earned income, the legislation would impose effective marginal tax rates that exceed 100 percent. Families of four would see effective marginal tax rates as high as 174 percent under the Senate bill and 159 percent under the House bill. Under the Senate bill, adults starting at $14,560 who earn an additional $560 would see their total income fall by $200 due to higher taxes and reduced subsidies. Under the House bill, families of four starting at $43,670 who earn an additional $1,100 would see their total income fall by $870.

In addition, middle-income workers could save as much as $8,000 per year by dropping coverage and purchasing health insurance only when sick. Indeed, the legislation effectively removes any penalty on such behavior by forcing insurers to sell health insurance to the uninsured at standard premiums when they fall ill. The legislation would thus encourage "adverse selection"—an unstable situation that would drive insurance premiums, government spending, and taxes even higher.In my view, the healthcare reform under consideration is so reckless and over the top that I can't believe it will ever see the light of day.

Conclusion: The health care bills that President Barack Obama is shepherding through Congress contain new taxes and new government subsidies, both of which would touch low- and middle- income Americans. The complexity of those tax-and-subsidy schemes makes it difficult for voters to discern whether they would be a net beneficiary or a net payer.

... low- and middle-income exchange participants would face often alarmingly high effective marginal tax rates. Even if such workers would receive subsidies under the House or Senate bill, they nevertheless would keep less of every additional dollar of income than they do today. Many would see their tax bills rise even as their real incomes fell. Those perverse incentives would set a low-wage trap for millions of Americans, discouraging them from climbing the economic ladder and encouraging them to remain dependent on taxpayers. Meanwhile, the legislation’s insurance regulations would encourage Americans not to purchase coverage—the opposite of the legislation’s intended effect.

Why zero rates are not driving the equity rally

I've been asserting for some time now that the equity market rally has nothing to do with the Fed's zero interest rate policy or with fiscal stimulus. Indeed, I think the rally continues despite the Fed's too-easy monetary policy and despite the terribly misguided fiscal stimulus policies coming out of Washington. Those are some mighty controversial assertions, given that there appears to be a multitude of observers who assert just the opposite—that the rally is a bubble, that the economy's strength is ephemeral, that the recovery is unsustainable, and that things are simply so bad that they can never get put right. For more than a year I've pointed out my rationale for, and the evidence of, a genuine recovery developing, but it can't hurt to put it all down in one place, and it might convince some of the skeptics.

But before I begin, let me say that the Fed's quantitative easing/zero interest rate policy was likely instrumental in averting a financial meltdown a year ago, and so the policy should get credit for setting the stage for recovery. Without a functioning banking system, a recovery probably would have been impossible. To be sure, the banking system is still not back to "normal" and many small businesses are having difficulty accessing credit. But that doesn't make a recovery impossible, nor does it ensure the demise of the current recovery; it only slows things down.

This recession turned into a profound recession right after the failure of Lehman Brothers in September '08. A worldwide panic ensued, in which the demand for money and risk-free assets rose astronomically and spending collapsed. If the Fed had not responded with an equally astronomical injection of bank reserves to the system, the financial panic would not only have led to a steep recession, but also to what would likely have been a painful deflation. The Fed did the right thing, but it took them awhile to figure it out. (The need for quantitative easing has long since passed, I think, but that is the subject of a separate debate.)

What follows is a recap of why I think the rally is genuine and not just the result of fiscal or monetary stimulus:

Printing money can never create growth. The only way an economy can grow at a rate faster than its population growth is if it can utilize existing resources in a more productive fashion; it it can produce more from a given amount of labor, capital, and resources. Gains in productivity, in turn, only result from great effort: from investment, from risk-taking, from saving, and from working harder and smarter. In an inflationary environment brought on by easy money, people tend to favor speculative activities (e.g. investments that pay off if prices rise, such as commodity speculation and real estate purchases) over productive activities (e.g., new plant and equipment, worker training, computers, infrastructure). In the extreme—something I learned from the years I lived and worked in Argentina in the late 1970s—an inflationary environment makes planning and productive investment virtually impossible. Everything becomes reduced to price speculation and survival. Look at the record of any country that has experienced high and rising inflation and you will find very little, if any, real growth. Alas, generations of Fed governors have failed to learn this lesson, and Mr. Bernanke in particular continues to believe that the Fed can fine-tune economic growth by raising and lowering the Federal funds rate.