I've been covering the explosive growth of M2 for almost two years now, and I'm very happy to report that M2 is no longer exploding. In fact, its annualized growth rate over the past 3 months has fallen to a mere 1.3%, down from its all-time, year-over-year high of 26.9% in February of last year. The source of the unprecedented M2 growth now looks almost certain to have been the frenzied federal spending which followed in the wake of the Covid shutdowns. That spending was effectively monetized by the Fed and the banking system, which in turn fueled an enormous increase in demand relative to output. All transpired in line with Milton Friedman's theory: "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it cannot occur without a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output."

Now, in the absence of any further Covid "stimulus" payments, and thanks to surging tax revenues (see my last post for more details), the Fed's decision to raise interest rates and shrink its balance sheet, all but ensure that there will be at least no further fuel poured on the still-raging inflation fire which was sparked about a year ago. In that sense it may be said that our current inflation episode will likely prove to be "transitory." But since we also know that inflation responds to excess money with a "long and variable lag," we are likely to see uncomfortably high inflation for at least the next year or so. How high and exactly for how long is anyone's guess at this point, but at least we can now see some light at the end of the inflation tunnel.

Not surprisingly, the bond market has figured this out. Inflation expectations have cooled in the past two months: the 5-year breakeven inflation rate embodied in the TIPS market has dropped from a high of 3.7% to now 2.9%. At the same time, the bond market has adjusted downward its expectation for the peak in the Federal funds rate. Thus the market now expects the Fed to raise its target rate to a maximum of about 3% a year or so from now, instead of 3.5% by the end of next year. To my mind this seems quite optimistic. But if the bond market is right then the economy is unlikely to suffer much and the equity market correction underway may be nearing an end.

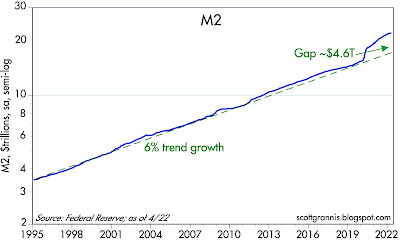

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of the M2 money supply as of the end of April (data released yesterday). As growth slows relative to its long-term 6% trend, the "gap" is shrinking. But it may take at least a year or two before it disappears, so I repeat what I said earlier this month: "M2 still has a lot of inflation potential."

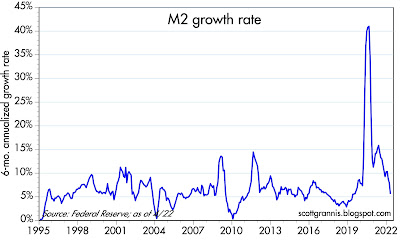

Chart #2

Chart #2 shows the year over year growth rate of M2. As noted above, M2 has hardly grown at all for the past three months, and the budget deficit is very likely to continue shrinking, so the year over year rate is almost certain to approach zero.

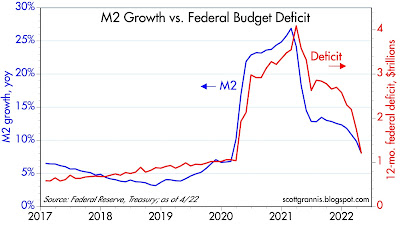

Chart #3

Chart #3 compares the growth of M2 to the level of the federal budget deficit. This is powerful evidence that the deficit was effectively financed by "money printing."

I hasten to add that this is arguably the first time in modern history that this has happened. Did the Fed allow this to happen? How exactly did M2 increase so explosively? Under our fractional reserve banking system, only banks can create new, spendable money; the Fed can only create bank reserves, which in turn are necessary for banks to create new money. Is Powell now being lauded for mopping up the mess he created? We don't know the full story yet, but I'm sure it will emerge.