The economy could be doing a lot better, but corporate profits are about as good as they get. Which suggests that the equity market rally still has legs.

Today we received the first revision to Q2/21 GDP, which included the first estimate of corporate profits for the period. GDP was revised upwards by a modest—though still impressive—amount, posting a 6.6% quarterly annualized growth rate. Corporate profits, on the other hand, soared at a 44% annualized rate, and are now at a new, all-time high. All of this despite the fact that the unemployment rate is still quite elevated (5.4%) and there are 6 million fewer people working than at the pre-pandemic high.

If there's a silver lining to the Covid cloud, it is here, in the form of a spectacular increase in the economy's productivity. And with many of those 6 million idle workers likely to be snapped up by desperate employers starting next month (when super-generous unemployment benefits expire), the economy has plenty of room to expand in coming quarters.

A storm still threatens on the horizon, unfortunately, in the form of the Democrats' $3.5 trillion so-called "infrastructure" reconciliation bill that just passed the House. If the spending it entails ever sees the light of day, it will result in a massive expansion of the welfare state and an equally massive and crushing new tax burden on all of us. The economy will find it very hard to thrive with so much spending, since there is almost certainly going to be many hundreds of billions of dollars wasted due to inefficiencies, perverse incentives, corruption and graft.

So if there's a silver lining to the Afghanistan cloud, it can be found in the recent and precipitous drop in Biden's popularity, thanks to his abrupt decision to surrender to the Taliban. Our ship of state is virtually rudderless, and it strains credulity to think that a seriously weakened administration can actually push through a radical expansion of the administrative state and a massive increase in income redistribution.

The charts that follow focus on corporate profits and GDP, both of which are looking pretty good these days. I also discuss the outlook for inflation, which is not very good. Finally, I discuss equity market valuation, which by several different measures is not at all outrageous. That's a very good thing.

Chart #1

Chart #1 gives some much-needed, long-term perspective on the economy's growth trajectory. For over 40 years, the economy followed a 3.1% annual growth track. That changed dramatically, however, in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008-2009. Since then, the economy has grown at about a 2.1% rate per year.

Chart #2 zooms in on Chart #1, showing just the past 20 years. Today's economy is about $4.5 trillion below what it would have been had it followed a 3.1% annualized growth track. That represents a potential loss of almost 20% in real national income. What also stands out is the economy's fairly rapid recovery to its 10+ year trend growth track in the past year.

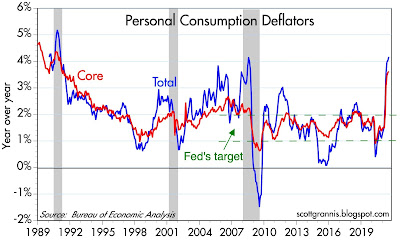

Chart #2 shows the quarterly annualized rate of inflation across the entire economy (i.e., the GDP deflator). Inflation according to this broadest of measures surged at a 6.2% annualized rate in the second quarter. That's the highest rate by far since the early 1980s.

Keynesians look at this surge in inflation as an inevitable—but likely only transitory—consequence of the massive monetary stimulus that was necessary in order to get the economy back on its feet in short order.

I agree that this surge in inflation has a monetary source, but I don't believe that expansive monetary policy is what drives a recovery. The Fed has no power to create jobs with its printing press. The most the Fed can do is to provide extra liquidity—which they did to the tune of almost $4 trillion—to satisfy the economy's desire for safety during troubling and highly uncertain times. Without that liquidity it might have been more difficult for the economy to recover. Indeed, the economy might have suffered more without an extra injection of liquidity, because markets might have seized up.

But looking ahead, an abundance of liquidity is not necessary. As confidence returns and jobs are added and profits increase (!), the economy doesn't need an abundance of liquidity. There's way too much liquidity these days, in fact, which is why short-term interest rates are virtually zero. Yet the Fed has not reversed course; they have not withdrawn excess reserves and they have not increased short-term interest rates. As a consequence "unwanted" money and liquidity are piling up and people are trying to get ride of it. They can only do this by spending the money on "things." But of course that doesn't make money disappear, since the person selling the thing I buy must in turn do something with the money he or she receives.

So the economy finds itself with an abundance of money and people are trying hard to spend that money by buying lots of different things. Real estate prices are up, food prices are up, hotel occupancy is up, private jet travel is surging, commodity prices are up, computer prices are up, and many more prices are up. Shortages are developing. Over time some shortages will disappear, but without the Fed taking action to drain liquidity, prices are unlikely to fall back to where they were. A new equilibrium will eventually be achieved in which most prices are higher (perhaps significantly so), the economy grows, and the current stock of money will have fallen in relative terms to a point in which people are no longer trying to reduce their money balances.

Chart #4

Chart #4 compares the level of economy-wide corporate profits to nominal GDP. Both are at all-time highs, and it's obvious that corporate profits have increased faster than nominal GDP in the past year.

Chart #5 shows corporate profits as a percent of nominal GDP. Profits have never been so strong relative to nominal GDP.

It's no wonder, then, that equity prices are also at all-time highs. We're in a profits nirvana of sorts, thanks in part to expansive monetary policy, but probably in large part due to corporate efforts to cut costs and streamline their business—all necessary to survival during times of Covid. Extremely low real interest rates are also a boon, since financing costs have never been so cheap.

Chart #7

Chart #6 is a long-term view of Chart #4. What stands out here is the surge in profits that began around the mid-1990s. Profits averaged about 5% of nominal GDP from 1959 through the mid-1990s, but then they surged to 8-10% of nominal GDP. Years ago I discussed the then-prevailing view among many bearish investors that profits were mean-reverting and would eventually fall back to 5-7% of GDP. I disagreed, since I saw the rise in profits as a boon triggered by globalization. China's big boom started in 1995, not coincidentally. As world markets globalized, successful firms found themselves operating in a much bigger market with seemingly endless possibilities. Chart #7 compares US corporate profits to global GDP, and by this measure not much has changed over time. (The chart only covers the period ending 12/20.) Since global GDP has grown faster than US GDP, global corporations have seen their sales rise relative to the size of the US economy.

Conclusion: it is not necessarily the case that profits have to fall back to some much lower level of nominal GDP. Profits are arguably sustainable at current levels. That further suggests that equities are not necessarily or fundamentally overvalued at current levels.

Chart #8 shows my calculation of the PE ratio of the S&P 500 using the National Income and Product Accounts measure of corporate profits (the source for profits shown in the above charts) as the "E" instead of the traditional 12-month trailing average of GAAP reported profits. Yes, PE ratios by this measure are high, but nowhere near as high as they were in 2000.

Chart #9 compares NIPA corporate profits to reported profits (12-mo. trailing average of adjusted profits, according to Bloomberg). These two different measures tend to track each other fairly well over the years, except that NIPA profits, being based on the most recent quarter, usually point the way to trailing profits. What that means is that there is likely more good news to come for the stock market.

Chart #10 shows the risk premium of the S&P 500, which I calculate by subtracting the 10-yr Treasury yields from the current earnings yield of the S&P 500 (which in turn is the inverse of the reported PE level). What we have today is a relatively attractive risk premium. Equities, in other words, are not necessarily overpriced at all. In fact, during the bull market of the 1980s and 90s, the risk premium was negative.

Brian Wesbury, Art Laffer and I all use a similar model to value the equity market. This model assumes that the discounted present value of future profits guides current market valuations. This is a capitalization model which essentially divides current profits by the current 10-yr Treasury yield to get a sense of where the fair value of stocks is. When discount rates are low, such as they are now (10-yr Treasury yields are only 1.3% or so!) then the fair value of equities should be high.

At this point one should be worried about what happens when interest rates revert back to a higher level (where they should be given the prevailing rate of inflation). Does the inevitable Fed tightening mean that the stock market is headed for another crash? Not necessarily.

By my calculations, equities today are priced to almost a 4% discount rate. If they were priced to a 1.3% Treasury yield, then the fair value of equities would be multiples of what it is today. In other words, the market is already assuming that rates rise, so rising rates needn't be the death knell for equity markets.

UPDATE: Since this post includes a description of how I see monetary policy becoming a force for rising prices, I recommend reading my June post on the subject of inflation in Argentina:

Argentine inflation lessons for the U.S.